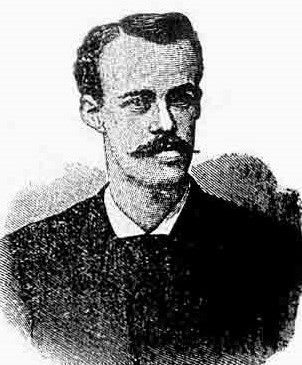

Jud Birchall

Hidden in obscurity after his death more than 130 years ago, A.J. “Jud” Birchall was the starting left fielder and leadoff hitter of the 1883 American Association champion Athletic Club of Philadelphia. A local schoolboy who grew up in Philadelphia’s Germantown neighborhood, Birchall had a three-year major-league career with the Athletics that culminated with one of the greatest pennant races in American Association history. Birchall and his teammates entertained large crowds at Jefferson Street Grounds during the 1883 season that ushered in a new era of baseball in Philadelphia and took the game to previously unseen heights of popularity.

Hidden in obscurity after his death more than 130 years ago, A.J. “Jud” Birchall was the starting left fielder and leadoff hitter of the 1883 American Association champion Athletic Club of Philadelphia. A local schoolboy who grew up in Philadelphia’s Germantown neighborhood, Birchall had a three-year major-league career with the Athletics that culminated with one of the greatest pennant races in American Association history. Birchall and his teammates entertained large crowds at Jefferson Street Grounds during the 1883 season that ushered in a new era of baseball in Philadelphia and took the game to previously unseen heights of popularity.

Adoniram Judson Birchall was born on September 12, 1855, in Germantown to Elias Birchall, an immigrant from England, and Sarah (Lutz) Birchall, the daughter of a shoemaker of German extraction. Jud, as he would be known, was the 10th of 15 children born to the Birchalls between 1843 and 1863.1 Of the 15 children, only eight survived to adulthood, including his older brother Edward, who was also a baseball player of local renown in Philadelphia. The elder of the baseball-playing Birchall brothers played left field for the Girard club of Philadelphia before embarking on a career as a civil engineer.

The well-documented business successes and philanthropic activities of Jud’s father, as well as the wealth of information available about the family’s history, gives us a glimpse into circumstances into which Jud was born.

Elias Birchall came to the United States with his parents when he was 6 years old. In early adulthood he became involved in manufacturing hosiery in Germantown. On December 8, 1842, he married Sarah Lutz, the daughter of Abraham and Elizabeth (Conver) Lutz, who were said to be “staid and fervent Christians.”2 The senior Birchall enjoyed great success in the textile industry and, over time, acquired a sizable fortune. His prominent position in Germantown’s commercial and social circles are an indication that Jud probably grew up in what would have been considered an upper-class family in late nineteenth-century Germantown. It is certain that young Jud’s material needs were met and education, including religious instruction, was stressed in the home.

Jud, or A.J., was named after Adoniram Judson, an early American Baptist missionary, lexicographer, and Bible translator, best known for his missionary work in Burma.3 The Birchalls were active members of the Milestone Baptist Church. Elias served the church as a deacon, trustee, and choir leader, giving liberally of his time and financial resources – to his own detriment in his later years – for the advancement and support of the church.4 Jud was raised with traditional nineteenth-century evangelical Protestant tenets that emphasized individual conversion, personal piety, Bible study, and public morality. Whether these were values he carried with him into adulthood is unclear.

Jud attended Rittenhouse Grammar School, a public school that served rich and poor families alike in the Germantown, Mt. Airy, Chestnut Hill, and Rittenhouse Town sections of Philadelphia.5 His first amateur baseball experience came in 1869 as a member of the Americus Club.6 This team was made up of members of the first senior class of Rittenhouse. Jud was one of only two players who were not members of the graduating class. Unlike his brothers, he never attended college and it is unknown how many years of formal education he completed. However, given his family’s commercial interests, he was identified as having the offseason vocation of weaver.7

It is unknown if Birchall threw right- or left-handed or from which side of the plate he batted. However, we do know that by the spring of 1870 the 14-year-old boy had set out to pursue a career in baseball, which always seemed to bring him back to his hometown of Philadelphia. Birchall played for three different organizations that used the name Athletic Club of Philadelphia.

The early years of Birchall’s baseball life were spent as an infielder, primarily at third base. He spent parts of 1870 with both the Athletics Jr. and United, one of the best amateur clubs in Philadelphia at the time. When the United disbanded, he joined the Germantown Alert and stayed with them until the end of the 1874 season.8 In 1875 he went to Wilmington and played third base for the Delaware Quicksteps. That year, the Quicksteps barnstormed across the Midwest and played against the Chicago White Stockings and Cincinnati Red Stockings. Although the Quicksteps were considered an amateur club, they were a commercial venture and had a roster that included paid players playing alongside true amateurs. The Quicksteps were on the edge of professionalism and by every account were one of the finest amateur nines in the region. The experience of playing for the Quicksteps proved invaluable to the young infielder, providing him with his first taste of professional competition.

Jud remained with the Quicksteps during the 1876 season before returning to Philadelphia in 1877 to join the Fergy Malone-led Athletics of the League Alliance. This version of the Athletics was reborn as a semipro team after the club was expelled from the National League for failing to complete its entire schedule during the 1876 season. Birchall also began the 1878 season with the Athletics, which again played independently. However, a late May tailspin, which included defeats at the hands of local amateurs, necessitated a shake-up that resulted in Birchall being drafted by the International Association’s New Bedford franchise, co-managed by Frank Bancroft.9

Bancroft, who honed his entrepreneurial skills in the theater industry, saw the moneymaking potential in baseball, and acquired Birchall in June. The 22-year-old third baseman joined future major-league stars George Gore, Roger Connor, and Harry Stovey on the New Bedford roster. While Birchall was with the club for just under a month, there was no shortage of baseball played. Bancroft treated his club like a theatrical group and reportedly scheduled 130 games that year. On the Fourth of July holiday, Bancroft scheduled a tripleheader for New Bedford and Hartford: an 8 A.M. game in New Bedford, an 11 A.M. game in Taunton, and a 4 P.M. game in Providence.10 Four days later, Birchall left the New Bedford team. Where he played during the remainder of the 1878 season is unknown. Birchall once again played for the hometown Athletics in 1879.

In 1880 Birchall joined future Hall of Famer Dan Brouthers on the Baltimore club of the loosely organized National Association. Birchall, beginning his transition from third base to left field, divided the third-base and left-field duties with utilityman Joe Ellick. The Baltimore team disbanded on June 29 and Birchall once again returned to Philadelphia, finishing the season with the Globe club.

In February 1881 Birchall signed with the Athletics and began his third and final stint with the team. The Athletics were now part of the Eastern Championship Association (ECAS) and boasted a roster that included Jack O’Brien, Cub Stricker, and Charlie Mason – all of whom played a prominent role on the 1883 American Association championship team. Unlike his previous associations with the club, Birchall stuck with the Athletics for the next three seasons, becoming an integral part of a lineup that later included established major-league stars like first baseman Harry Stovey and ace right-handed pitcher Bobby Mathews.11

The Athletics joined the American Association in the fall of 1881 and on May 2, 1882, the 26-year-old Birchall made his major-league debut, patrolling left field and batting cleanup for the Athletics in Oakdale Park, located on Eleventh and Cumberland Streets.12 Birchall went 2-for-4 with a walk and a run scored as the Athletics beat the Baltimore Orioles 10-7 in the first-ever American Association game. Birchall batted in the cleanup spot during the early part of season before moving to the leadoff spot he customarily occupied for the next year and a half.

During his rookie season, Birchall earned a reputation as a steady left fielder with a flair for making incredible catches. One such instance was during a game against the Cincinnati Red Stockings on June 1, when he made a spectacular game-saving catch that the Philadelphia Inquirer described as “the most wonderful ever witnessed on the ball field.” With Philadelphia leading 3-0 in the top of the ninth, Cincinnati was threatening with runners on second and third and two down. Red Stockings first baseman Henry Luff sent a rocket to left field. The Inquirer recounted the play as follows:

“Luff hit a ball that traveled like a shot out of a cannon directly over Birchal’s [sic] head. The later jumped fully three feet from the ground, and the ball struck his right wrist, bounded in the air, fell into his hand and then dropped, but before it reached the ground Birchal [sic] cleverly caught it with one hand, and the Cincinnatis were ‘Chicagoed.’”13

Birchall enjoyed a fine rookie campaign. He appeared in all 75 of the Athletics’ games that season, 74 in left field and one at second base. He finished the season with career highs in batting average, .263, and RBIs, 27, both fourth-best among the team’s regulars. He also led the team in plate appearances, at-bats, and runs scored, while finishing second on the club in both hits and doubles. More importantly, he established himself as the Athletics’ everyday left fielder and a reliable leadoff hitter.

Following his steady performance during his rookie year, much was expected of Birchall and the Athletics in 1883. In its annual Baseball Preview, Sporting Life tabbed the Athletics as the American Association favorites and highlighted Birchall’s steady left-field play and excellent baserunning: “He is credited with some remarkable catches in his position, his running catches bring noteworthy. His great forte, however, is in base running, in which he leads the players of the country, and which has made him famous.”14

Stolen bases did not become an official statistic until 1886, so Birchall’s baserunning skills are difficult to assess in comparison with his contemporaries.

The 1883 season marked the Athletics’ return to the newly renovated Jefferson Street Grounds, which the New York Times hailed as the prettiest ballpark in America. It was reported that landscape gardeners made the playing field as “level as a billiard table.”15 The Athletics’ return to Jefferson Street Grounds presented a unique challenge to Birchall and the other Athletic outfielders. The ballpark, formerly known as Athletics Park, featured tight narrow corners in left and right fields and deep power alleys that met a cavernous 500 feet away in dead center field. The oddly-shaped ballpark tested outfielders’ awareness of where they were at on the field and their range to cover the vast power alleys.

In addition to having the finest ballpark in America, Philadelphia also had a brand-new entry in the National League. For the first time Philadelphia was a two-team major-league city, marking the beginning of a period of unprecedented growth in the popularity of baseball in the city.

Birchall and his Athletics teammates were so well received by the city of Philadelphia, that by early June their NL counterparts received permission from the League to reduce admission from 50 cents to 25 cents to allow them to compete with their popular crosstown rivals. Amazingly, the Athletics drew more than 300,000 fans16 to the Jefferson Street Grounds that season, including more than 45,000 for an early September four-game series with the second-place St. Louis Browns.

For Birchall the 1883 season marked the zenith of his major-league career. Although his batting average dipped 22 points from the previous year to .241, Birchall led the Association in both plate appearances and at-bats, establishing major-league records of 468 and 448, respectively.17 He also ranked fifth in the Association in runs scored with 95. Batting in the leadoff position, Birchall often set the table for Lon Knight, O’Brien, and Stovey, who batted .304 and smacked 14 home runs that year.

Despite charging out of the gate to an 18-3 mark in May, the Athletics were later locked in a tight three-way pennant race with the St. Louis Browns and Cincinnati Red Stockings. On August 10, in the midst of a three-game series in New York with the Metropolitans, the Athletics clung to a slim two-game lead over the Browns and were facing future Hall of Famer and Metropolitans ace Tim Keefe. Trailing 3-1 in the eighth inning, Birchall, in his customary role as a table-setter, ignited a two-run rally with a base hit off Keefe and heads-up baserunning. With the game tied 3-3 in the 10th, Birchall smacked a long triple to right field and scored on Stovey’s game-winning single, helping the Athletics maintain their slim lead over the Browns,

Not known for his power, Birchall hit only one home run in his major-league career. Fittingly, it came during the Athletics championship season and in the midst of the pennant race. On September 13, 1883, at Recreation Park in Columbus, Ohio, Birchall led off the game with an inside-the-park home run off right-hander Frank Mountain. The Athletics went on to win the game, 11-5, and opened up a seemingly safe 3½-game lead over the Browns, who dropped a 3-0 decision to the Baltimore Orioles the same day.

As the 1884 season opened, the Athletics and their fans anticipated another American Association pennant run. Birchall began the season in left field and batted in his customary leadoff spot, the catalyst of the returning offensive juggernaut. However, the Athletics quickly faltered and Birchall’s playing time witnessed a dramatic fall-off. Birchall appeared in only 54 of the team’s 107 contests, and by mid-May was dropped to the sixth and seventh slots in the Athletics batting order for the remainder of the season. Although he batted .258, his power numbers had declined significantly – he recorded only four extra-base hits – and his fielding was nowhere near what it had been two seasons before. By the end of the season, Birchall rarely appeared in the Athletics lineup, replaced by Henry Larkin, and the Athletics had fallen to seventh place in the Association. At the end of the season, Birchall’s major-league career came to a quiet end.

On January 1, 1885, Birchall married Emma Jane Pinkerton. Emma Jane was the daughter of John and Margaret Pinkerton, also of Germantown. The Pinkerton men were typically employed as blacksmiths while the women worked in the hosiery business. It is unclear when the romance between the two began, but it is hard to imagine the two hadn’t known each other nearly their entire lives.

Despite not being offered a contract by the Athletics in 1885, Jud felt he still had some baseball left in him. So in the spring of that year, he left his then-pregnant wife in Philadelphia and headed to New Jersey, where he joined the minor-league Newark Domestics. Reunited with former Athletics teammate “California” Bob Blakiston, Birchall primarily played left field for the Domestics, who finished 42-49, good enough for fourth place in the financially struggling Eastern League. After the season Birchall returned to Philadelphia and prepared for the birth of his first child. On November 25, 1885, Jud and Emma Jean Birchall became the parents of a son, Judson Elias.

Jud Birchall appeared in 225 major-league games, compiling 254 hits in 1,007 at-bats for a .252 batting average. Although his major-league totals are modest and his career described as undistinguished by some baseball historians, the official statistics probably don’t provide us with an accurate picture of the important role Birchall played in the Athletics’ pennant-winning season of 1883. According to David Nemec, author of The Beer and Whiskey League, there was a distinct difference in philosophy between NL and AA official scorers, and the fact that Birchall played in the American Association “probably deducted 5-10 points from his batting average.”18 AA official scorers were typically stingy in awarding hits, while NL scorers tended to be more liberal in their scoring decisions.

In addition to the discrepancies and inaccuracies associated with statistics from this era (and the American Association in particular), stolen bases were not an official statistic until 1886. Consequently it is difficult, in any reliable manner, to quantify or compare Birchall’s baserunning abilities. Yet, at the time of his death, his baserunning and “wonderful slides into second were still talked about in baseball circles.”19

When compared to his contemporaries, Birchall’s career fielding statistics would indicate that he was a slightly below average left fielder. His statistical plunge in fielding percentage following his outstanding rookie season of 1882, when he was one of the better left fielders in the Association, raises many questions.

Was this drop-off the result of the early signs of consumption that would eventually take his life? At least two independent sources suggest that Birchall’s playing career was cut short due to failing health. However, the fact that he died more than three years after the end of his major-league career would indicate that the pulmonary trouble that led to his demise may not have been contracted or progressed far enough to begin impacting his playing ability. Therefore, baseball historians are left to search for other clues that may have contributed to his fall-off during a time when he should have been entering his prime.

It’s possible that Birchall’s off-field activities contributed to his fall-off. As with many teams during the 1880s, there were numerous reports of heavy drinking among the Athletics. In fact, the Athletics management expressed concerns about almost all of their players during the 1883 season, which resulted in management establishing a set of club rules that among other things addressed the primary vices of hard living associated with the Athletics and ballplayers of this era. However, no one player or group of players was mentioned by name, so it is difficult to know if this may have contributed to Birchall’s decline.

His playing career complete and health beginning to fail, Birchall spent the next two summers umpiring in amateur leagues in and around Philadelphia.

On December 22, 1887, Jud Birchall succumbed to consumption (tuberculosis). He died quietly at his home on Main Street in Philadelphia and was buried in the Milestone Baptist Church Cemetery. The cemetery was later destroyed for construction and Birchall was reinterred in a common mass grave in Cheltenham, Pennsylvania.

After Birchall’s death, Emma worked as a dressmaker. She and Judson moved in with her sister, Sarah Pinkerton. Judson grew up to be a haberdasher and died in 1911 at the age of 25. In 1916 Emma married William Parsons, who worked for an electric storage company. The couple were married for at least 34 years, as the 1940 census shows them residing in Philadelphia.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author relied on Baseball-reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Willoughby H. Reed. History and Genealogy of the Reed Family (Norristown, Pennsylvania: Norristown Press, 1929), 206.

2 Reed, 205.

3 Fred Barlow, “Adoniram Judson, Worldwide Missions.” Retrieved from wholesomewords.org/missions/bjudson1.html.

4 Reed, 207.

5 The school was named after David Rittenhouse (1732-1796), a noted American clockmaker, mathematician, astronomer, educator, and state politician. As an astronomer he is credited with calculating the transit of Venus as well as making a successful observation of the planet. In later years he was a vice provost and professor of astronomy at the University of Pennsylvania. He was also the first director of the United States Mint.

6 “A.J. Birchal [sic],” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 23, 1887: 1.

7 “The Base Ball Parade,” Times (Philadelphia), October 2, 1883: 1.

8 “A.J. Birchal [sic].”

9 “General Notes and News,” Chicago Tribune, June 16, 1878: 7.

10 “Base Ball,” Buffalo Courier, July 4, 1878: 2.

11 Harry Stovey was the greatest power hitter in American Association. Bobby Mathews won 30 games in three consecutive seasons for the Athletics (1883-1885).

12 Jerrold Casway, “Jefferson Street Grounds,” National Pastime, 2013: 14.

13 “Chicagoed” was the nineteenth-century term to describe a team that had been shut out. Philadelphia Inquirer, June 2, 1882.

14 The Athletics Club; the Men Who Will Strive for the American Association Championship,” Sporting Life, April 15, 1883: 2.

15 M. Benson, Ballparks of North America: A Comprehensive Historical Reference to Baseball Grounds, Yards and Stadiums, 1845 to Present (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Publishers, Inc., 1989), 296.

16 Edward Achorn, The Summer of Beer and Whiskey (New York: Public Affairs, 2006), 243.

17 Birchall’s major-league record for plate appearances and at-bats was broken in 1884.

18 David Nemec, personal correspondence, July 30, 2004.

19 “‘Jud’ Birchal [sic] Dead: The Famous Left Fielder of the Athletic Base Ball Club,” Times (Philadelphia), December 24, 1887: 1.

Full Name

Adoniram Judson Birchall

Born

September 12, 1855 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

Died

December 22, 1887 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.