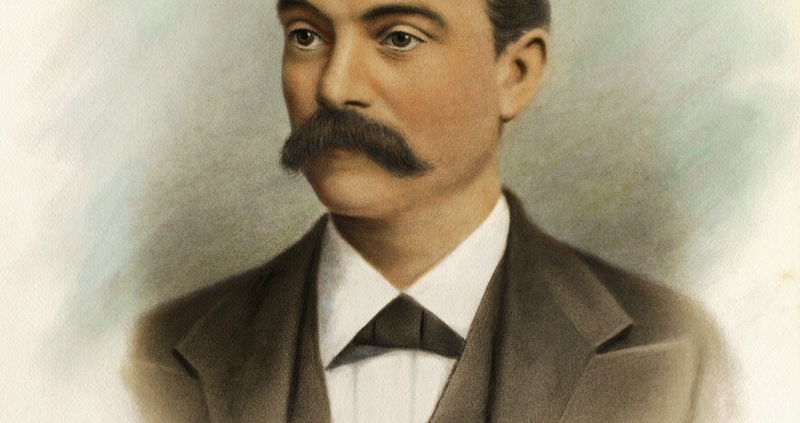

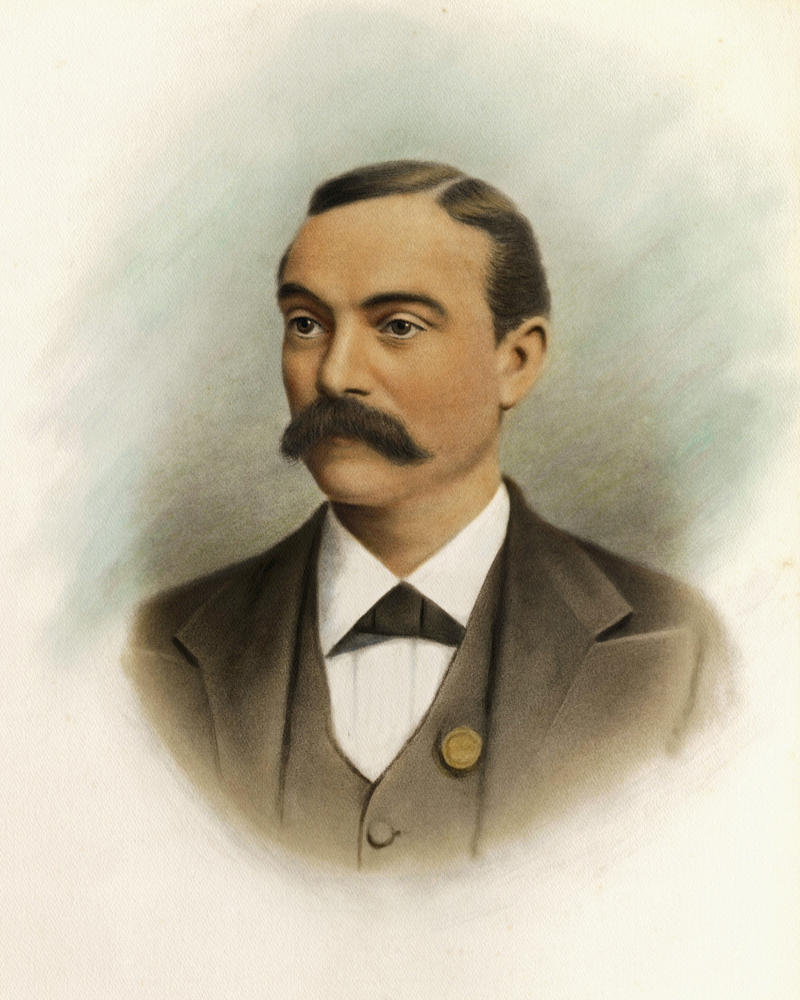

Fergy Malone

Long before catchers crouched behind home plate in padded armor, Fergus George “Fergy” Malone was redefining toughness—and the game itself—with nothing but bare hands, Irish grit, and a bat-ready stare. Largely forgotten today, Malone was a baseball pioneer and recognized and respected in his time as a pivotal figure in the game, especially in the region around Philadelphia. He was among an early group of men who helped transform baseball from a regional, New York City-based pastime to the country’s National Game and elevate the sport from an amateur to a professional endeavor. Some of the tactical fielding elements he employed—and even some of the equipment he wore—had a lasting impact and modernized the catching position. Over the course of his 30 years in baseball, Fergy Malone became one of the sport’s first “lifers.”

Long before catchers crouched behind home plate in padded armor, Fergus George “Fergy” Malone was redefining toughness—and the game itself—with nothing but bare hands, Irish grit, and a bat-ready stare. Largely forgotten today, Malone was a baseball pioneer and recognized and respected in his time as a pivotal figure in the game, especially in the region around Philadelphia. He was among an early group of men who helped transform baseball from a regional, New York City-based pastime to the country’s National Game and elevate the sport from an amateur to a professional endeavor. Some of the tactical fielding elements he employed—and even some of the equipment he wore—had a lasting impact and modernized the catching position. Over the course of his 30 years in baseball, Fergy Malone became one of the sport’s first “lifers.”

Though of average stature at 5-feet-8 and 156 pounds, Malone was nevertheless one of the early game’s finest hitters. He showcased his athleticism and deep knowledge of the game by playing every position on the field.1 By the end of his baseball career in 1892, Malone had achieved the relatively rare distinction of having played, managed, and umpired at the major-league level.

Malone was called “one of the first…really great baseball catchers” and, indeed, was one of the first left-handed throwing catchers.2 In an era before protective equipment was widely used and despite the physical risks, he was one of the early “tough guy” catchers who positioned themselves close to batters to deter base stealing.3 Fergy remarked of that time, “When I caught [Dick] McBride and ‘Ed’ Leach, they were admittedly the hardest and swiftest pitchers in the business; yet I had to go behind the bat with bare hands and minus the least protection for my body. In those days we didn’t mind a trifle like that.”4

While Malone took risks behind the bat, he didn’t completely eschew the most rudimentary “tools of ignorance.” He is believed to have been an early adopter of lightweight, fingerless gloves to soften the blow from pitchers’ swift underhand deliveries.5

Fergy Malone was among a group of the first Irish-born professional players in the National Association of Base Ball Players (NABBP), America’s original baseball organization. And when the first wholly professional league, the National Association (NA), debuted in 1871, Malone became one of the first major-league players born in Ireland.6

In seven big-league seasons comprising 220 total games, the righty-hitting Malone batted .274 with one home run, 157 RBIs, and 200 runs scored. As a player-manager for major-league teams in 1873, 1874, and 1884, he recorded 47 wins and 66 losses, but Fergy’s statistics at the top level represent only a fraction of his much broader, richer baseball career.7

Born in August 1844 near Ballinderry, County Tyrone, Ireland, Fergy was the son of John Malone and Rosanna Bennigan.8 In 1852, towards the end of the Great Famine, the Malone family immigrated to America and settled in Philadelphia.9

Malone’s athletic pursuits began as a teenage cricket player with the Oxford Club in the Frankford section of Philadelphia.10 He applied his cricket-honed skills to baseball, debuting on October 31, 1862, at shortstop with the Athletic Base Ball Club in a game against a city rival, the Olympic Ball Club.11

The following year, Fergy joined the Athletics as a full-time player at age 19; however, his participation was suspended for the first half of the season to support his family while his two brothers served in the Civil War.12 He returned to the Athletics in August 1863 as their primary pitcher, replacing Tom Pratt, who had been drafted into the military.13 He pitched swiftly and even brilliantly at times; however, though talented, he battled inconsistency and control issues as a young pitcher. Nevertheless, the Athletics won three of the four games he pitched towards the end of the 1863 season.14

Malone and his sweetheart, Sarah Josephine Delaney, marked a major life milestone when they married on January 7, 1864, in Philadelphia.15 The couple went on to have 11 children while residing mostly in Philadelphia, aside from a few years when Fergy’s baseball career took the family to Washington, D.C.16

The 1864 season was another shortened one for the Athletics owing to the heightened tensions of the war. Malone ceded pitching duties and moved to the infield. He appeared in most of the Athletics’ nine games and displayed defensive versatility by playing all five infield positions.17 Fergy’s season was partially interrupted in July when he enlisted in Pennsylvania’s 196th Regiment Volunteer Infantry (also known as the Fifth Union League Regiment). He rose to the rank of corporal and served alongside his Athletic teammates Dick McBride, Bill Parks, and Ned Cuthbert. The regiment spent most of its time guarding Confederate prisoners of war at Camp Douglas near Chicago before disbanding and being mustered out in mid-November.18

Malone began 1865 as a member of the Athletics and participated in a club practice game in late April.19 In early May, both he and Ned Cuthbert left the club to join a crosstown rival, the Keystone Base Ball Club. Malone likely left the Athletics to gain more playing time with the less competitive Keystones. He proved to be one of the Keystones’ most consistent hitters and fielders, playing in 19 of the club’s 21 games. While Malone opened the season playing infield, he emerged as the Keystones’ starting catcher by late July—a role he would retain for the remainder of the 1865 season.20

As soldiers returned from Civil War battlefields, baseball’s popularity surged, spreading rapidly across the country. Amateur clubs sprang up in cities, towns, and rural communities, serving as emblems of civic pride. Baseball became a means to project civil vitality and attract new residents. Once a regional pastime largely confined to the Mid-Atlantic region, the game in the immediate postwar years was rapidly transforming into a national obsession.21

In September 1865, a group of attorneys and prominent businessmen in Wilmington, Delaware—a burgeoning industrial city—founded the state’s first organized club: the Diamond State Base Ball Club.22 With grand ambitions to dominate local play and compete favorably with clubs outside Delaware, they joined the NABBP.23 In 1866, the club bolstered its inexperienced squad by recruiting two experienced players from the Philadelphia Keystones, Fergy Malone and Andrew Gibney. The two formed a formidable battery and became foundational members of the developing young squad.24

Though early baseball celebrated amateurism and local roots, the postwar era saw the rise of “revolvers”—seasoned players imported from outside communities, often compensated under the table. This practice, though increasingly widespread, stirred controversy. As hundreds of new clubs emerged in late 1865 and into 1866, the competition for top talent intensified. Clubs who prioritized winning began playing fast and loose with the NABBP’s rule compensating players. Instead, these clubs offered jobs—sometimes no-show positions—or business opportunities instead of direct salaries.25 It’s likely that the Diamond State’s well-connected founders enticed Malone to Wilmington by setting him up with a cigar shop—an arrangement that allowed him to earn a living while avoiding a direct breach of association rules.26 The fact that Fergy’s brother John had relocated to Wilmington a year or so before him may have been an added incentive.27

Malone’s lone season with the Diamond States was nothing short of exceptional. He was undefeated as the club’s primary pitcher, winning all 10 games he pitched and proving, alongside Gibney, to be one of the club’s most reliable hitters.28 The pair led the Diamond States to a 14–2 record, which included an 1866 Delaware state championship and several wins over Pennsylvania clubs.29

Yet Malone’s time in Wilmington was not without controversy. That season, the Diamond States challenged the reigning state champions—the Atlas Base Ball Club of Delaware City—to a best-of-three series for the title. Before the opening game on June 8, the Atlas lodged a protest, alleging that Malone was an active member of the Athletic Club of Philadelphia and was therefore ineligible to play for the Diamond States according to NABBP rules. Despite the objection, the game went forward. Malone starred, both at the plate and on the mound, as the Diamond States secured a decisive victory, much to the frustration of their rivals. What followed was a heated, six-week-long exchange waged publicly through the local press. Ultimately, the Atlas withdrew from the remaining two series games, and the Diamond States claimed the title by default.30

Although Malone’s time with the Diamond States was memorable, he was recruited back to Philadelphia by the newly formed Quaker City Base Ball Club for the 1867 season.31 The Quakers bolstered their roster—undoubtedly with financial incentives—by adding other seasoned players from national-class clubs, including Tom Pratt and Jack Chapman of the Atlantic Base Ball Club of Brooklyn, Patsy Dockney of the Athletics, and William Wallace and William Shane from the Keystones.32 While the club aspired to challenge the Athletics and Keystones for city supremacy, they lost all four games on the field against those squads, winning only one through a Keystones’ forfeit. Still, Quaker City finished with a strong 28-9 record. Malone, who took over at starting catcher after Dockney left the club for the Eurekas of Newark, New Jersey in late June, also filled in at all four infield positions. He led the team offensively, scoring 152 runs in 34 games.33After witnessing several of his stellar performances in 1867, newspaper editor and Athletics co-founder Colonel Thomas Fitzgerald declared Fergy “second to no player in the country. He made a clear score by splendid batting, while his catching was beautiful and strong.”34

Malone’s return to his adopted city was short-lived. In 1868, he was enticed to move to the nation’s capital to play for the up-and-coming Olympic Base Ball Club, which, along with their D.C. and NABBP counterparts, the National Base Ball Club, regularly competed against top-flight teams outside Washington. With the move south, Malone was rewarded with a U.S. Treasury Department clerkship arranged by the Olympics’ officials.35 He excelled in both the outfield and behind the plate for the Olympics that season, leading the 12–11–1 club with 74 runs and tying for the lead with 79 hits.36

With illicit pay-for-play rampant in amateur baseball, the NABBP amended its rules to allow professional clubs to compete alongside, but grouped separately from, amateur organizations beginning in 1869.37 Malone’s Olympics were one of 12 clubs who chose to enter the professional ranks. Although they lost two starters to other clubs, the Olympics managed to sign four new players.38 The 1869 season was a breakout one for the team, as they finished 22–14 overall (9–12 versus professional clubs) and were crowned “champions of the South.” The season’s highlights included a three-week tour facing opponents in Ohio, Kentucky, and Pennsylvania; two courageous, notable, and controversial games against local African American clubs; and a long-anticipated series dominance over their rivals, the National Club, in which the Olympics won four of five games.39 Malone was his team’s most consistent hitter in 1869, leading the club with 92 hits and 100 runs scored in 25 games, while also piloting the defense at catcher.40 During his tenure in Washington, Malone developed into one of the pro ranks’ most reliable catchers. A decade after his tenure in Washington, a local newspaper recalled Malone’s effortless ability to snag foul-bound balls behind the bat.41

Before the 1870 season, competitors raided the Philadelphia Athletics, taking a third of their starting nine, including catcher John McMullin.42 To fill that key position, the club convinced Fergy Malone to return to his hometown for a second stint. Over the next two seasons, he and pitching ace Dick McBride emerged as professional baseball’s “most famous battery.”43 Malone demonstrated remarkable durability in 1870, missing only three of the club’s 77 games and leading the team with 241 hits. However, the Athletics were unable to improve their standing in the NABBP’s pro ranks, finishing in fourth place for the second consecutive season.44

As tension between the NABBP’s amateur and professional factions reached a breaking point in early 1871, nine professional clubs, including the Athletics, left the organization to form the first wholly professional league, the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players—more commonly called the National Association (NA).45 The Athletics edged out Boston and Chicago to take the pennant in the league’s inaugural season.46 The crafty and swift-throwing McBride, along with the rock-steady Malone, teamed up on 18 of the championship club’s 21 wins. At the plate, Fergy posted a .343 batting average, ranked second on the club in on-base percentage (.385) and stolen bases (9), and was third in total hits (46) and RBIs (33).47 Despite battling illness and a sore throwing arm, Malone persevered and missed only one championship season game against NA opponents.48

Age, injuries, and player turnover led to significant roster changes for the 1872 Athletics. Malone remained for what would be his final season with the club.49 He shared catching duties with newcomer Mike McGeary—starting 24 games to McGeary’s 23—and played another 17 games at first base. With the influx of younger, higher-performing starters like McGeary, Denny Mack, and Cap Anson, Malone was no longer one of the club’s top stars. Still, he posted a respectable .282 batting average, with 60 hits and 46 runs scored for the Athletics, who had a disappointing fourth-place finish.50

The next season, Malone joined, helped assemble, and became captain of a new Philadelphia entry into the NA, the Philadelphia Base Ball Club. They were known variously as the Philadelphias, White Stockings or Whites, Quakers, and Fillies or Phillies. Fergy and four Athletics comprised the core of the talented new club, which opened the season with a strong 8–2 start before Malone was unexpectedly replaced as field manager by teammate Jimmy Wood.51 The team led the league standings until an epic second-half collapse left them in second place behind Boston at season’s end. Malone had what would be the last great season of his playing career in 1873, catching all 53 games for the Philadelphias. He led all NA catchers with a .898 fielding percentage and placed second in putouts (198) and assists (48). Offensively, he batted .290 with 75 hits and 59 runs.52

Rumors circulated at the end of 1873 that Malone might be among the players joining the NA’s newly constituted Chicago White Stocking club in 1874. Despite Fergy’s public protests that he would rather retire than relocate, the lure of a $2,800 salary—then the highest in baseball—proved too great to refuse.53 Chicago lured not only Malone but also five of his Philadelphia teammates, including Jimmy Wood. Fergy assumed the captaincy during the first half of the season while Wood recovered from leg amputation surgery.54 Malone caught 47 of the club’s 59 games and remained one of the league’s top defensive catchers. However, his offensive output declined, batting .251 with 56 hits, placing him among the least productive starters on the roster.55

Malone entered the 1874 offseason as one of the NA’s veteran leaders at the age of 30.56 In 1875, he returned to the Philadelphias—now nicknamed the Pearls—serving mainly as a change first baseman. He collected just 28 hits, scored only 15 runs, and logged a modest .228 batting average in 29 of the fifth-place club’s 70 games. Malone left the Pearls at the end of the 1875 season.57

When the NA dissolved in early 1876, the Athletics were selected to represent Philadelphia in the new eight-team professional National League (NL), with the rival Pearls being relegated to independent professional status.58 The Athletics lost starting catcher John Clapp in the offseason when the St. Louis Browns won a bidding war for his services.59 By mid-May 1876, the club was struggling badly on the field and desperately needed a catcher to handle the speedy pitches of ace Lon Knight. Athletics management reluctantly turned to Fergy Malone, despite reservations about signing him. Unfortunately, Malone’s best playing days were behind him, and he struggled both offensively and defensively, as club leaders had feared.60 He played in only 22 league games from May 23 through July 15 for the moribund Athletics—20 at catcher, three in right field, and one at shortstop—before leaving the club. Malone hit just .229 with 22 hits and 14 runs scored. Aside from a lone appearance eight years later, 1876 would be his final season as a major-league player.61 As fate would have it, the NL expelled the Athletics and the end of the season for failing to finance a trip west to complete their full league schedule.62

The 1877 season proved to be a low point for both professional baseball in Philadelphia and Fergy Malone’s playing career to that point. The National League expelled the Athletics at the end of the 1876 season for not completing their league schedule, and the city was without a major-league team. As for Malone, he was hardly done with professional baseball, though the remaining NL clubs had little use for a catcher who would turn 33 during the season.63 In the spring of 1877, he reorganized the Philadelphia Base Ball Club, a professional minor-league team in the loosely affiliated League Alliance.64 As the club’s business manager, Malone was charged with assembling a starting nine, securing a home field, purchasing uniforms, and scheduling opponents.65 He also was the field manager and started at second base in three of the Phillies’ first four games, before being sidelined for the season with a hand injury.66

Unfortunately, Malone’s new club lacked organization and financial backing and was plagued by internal dissent right from the start. Following an opening day road win over the Athletics on May 12, Malone accused the host club of withholding a fair share of the gate receipts.67 The Phillies followed up with a victory over the Keystones, then lost their next four games.68 A players’ mutiny occurred in early June after Malone released two starters he believed were gambling on games. Led by center fielder John McMullin, the players countered that Malone had deprived them of due compensation and objected to his management style. McMullin and seven other starters broke from Malone and formed a reconstituted Philadelphia Base Ball Club.69 Malone kept his team’s uniforms but he and newly appointed general manager P.F. Hagan were unable to revive their club.70 McMullin was able to hold his Phillies together only through July 28, at which point the cash-strapped club disbanded.71

In 1878, Malone sought distance from the turmoil of the previous season and relocated to San Francisco to catch for the California Base Ball Club of the Pacific Baseball League, a professional minor league based in the Bay Area. As one of the club’s top two hitters, he batted .434, collecting 33 hits in 76 at-bats, and helped the Californias finish as league pennant runners-up. He also served as an umpire for several league games. Although Malone was able to briefly recapture the form of his earlier playing days, he returned home to his family in Philadelphia at the end of the season.72

The following year, a National Association minor league team in western Massachusetts, the Holyoke Base Ball Club, called on Fergy Malone to become their business manager and serve as a player and field captain.73 He batted third in the lineup and was Holyoke’s starting right fielder and change catcher. In eight games, he hit a respectable .333 with 12 hits in 36 plate appearances.74 Malone was granted his release from the club after their April 28 game, which may have been hastened by his negotiations with the Oakland Base Ball Club of the Pacific Base Ball League.75 The deal fell through in late May as the Oaklands declined Malone’s request for a $100 monthly salary and reimbursement for rail travel to California.76

For the rest of May and into early June, Malone occupied himself by umpiring National Association games in Philadelphia, most of which involved the Defiance Base Ball Club. By mid-June, he returned to the playing field as a substitute for three games with the Defiance Club and two with the Trenton Base Ball Club of New Jersey.77 Malone’s playing season ended on June 27 after he suffered a broken finger while catching for the Trentons.78

Before his injury, Malone had turned his attention to forming a new “first-class” independent club dubbed the Representative Nine of Philadelphia. The Representatives’ lineup was to include Fergy, former Athletic greats Al Reach and Wes Fisler, several of the Defiance Club’s starting nine, and banned National Leaguer Jim Devlin.79 While those plans never came to fruition, Malone instead arranged an ill-advised, two-game series beginning on Independence Day in Maryland between the Defiance Club’s starting nine—billed as the Athletics of Philadelphia—and the Baltimore Base Ball Club. The unauthorized move so rankled Defiance and Athletic brass that Malone was not hired back to umpire any other National Association games for the rest of 1879.80

The 1880 and 1881 baseball seasons passed without Malone appearing as a player, manager, or umpire. He devoted his time to assisting his wife Sarah with their Northeast Philadelphia grocery store.81

In early 1882, he returned to organize and manage the Atlantic City Base Ball Club. The independent minor-league club primarily faced opponents in the South Jersey and Philadelphia areas.82 The team was competitive on the field but lacked funding and fan support. The sandy surface at the Atlantics’ home field also proved unsuitable for competitive play. The ball club disbanded in early September after three of Malone’s starting nine signed with other minor-league teams.83

In August 1883, the Quickstep Base Ball Club of Wilmington, a Delaware minor-league club in the Interstate Association, was struggling with internal strife and mired in last place with a 31–49 record. Team stockholders turned to Fergy Malone, a Wilmington diamond legend from an earlier era, to help manage the club for the rest of the season.84 He hastily recruited a new battery, implemented stricter team rules, and led the previously floundering Quicksteps to a .500 record in their final 34 games.85

In October 1883, former Athletic teammate and president of the new Philadelphia Keystones, Tom Pratt, enlisted Malone as manager and catcher of his fledgling Union Association club.86 Unfortunately, Pratt’s team was undercapitalized, critically short on talent, and managed only a 21–46 record before folding in early August 1884.87 Fergy played only in the Keystones’ season opener, collecting one hit in four at-bats and catching the entire game—a notable feat for a 39-year-old who likely faced overhand pitching for the first time and did so without a chest protector or shin guards.88

Within a week of leaving the Keystones, Malone began a brief and largely unremarkable month-long stint as a National League umpire, officiating just 14 games during the 1884 season. He would return to the NL eight years later as a substitute umpire for one game.89

After a two-season hiatus from baseball, Malone landed the manager’s job with the Williamsport Base Ball Club, a minor league team in the Pennsylvania State Association of Base Ball Clubs (PSABBC). He led the 1887 Williamsport team to a 18–19 record, before securing his release at the end of July to take the same post with the Scranton Base Ball Club of the International League.90 Malone took over on August 1 with high hopes but was unable to improve the beleaguered and talent-short club’s standing, going 9–29 in the final two months of the season. Scranton finished with a 19–55 record, tied with Wilkes-Barre for last place.90

The 1888 season was Malone’s last as a field manager. He was hired the previous December by the Allentown Base Ball Club. They belonged to the newly formed Central League, a minor-league consisting of teams from northeastern Pennsylvania, southern New York, and New Jersey.91 Although Malone guided the club to a 9–5 league record, Allentown released him on May 21 amid costcutting measures.92

While playing professional baseball, Fergy had been engaged in a variety of occupations to supplement his income. Aside from running the Wilmington cigar shop and his clerkship at the U.S. Treasury in Washington, he worked as a baker, operated a liquor store and the aforementioned grocery, and served as a patrolman with the Philadelphia police. After leaving baseball, Malone returned to the U.S. Treasury Department as a special inspector at the Philadelphia Customs House. The position took him to Kalispell, Montana, in 1895; back to Philadelphia in 1896; and ultimately to Seattle, Washington, in 1902.93

Malone died unexpectedly in Seattle on January 18, 1905, at the age of 60 and was buried at New Cathedral Cemetery in Philadelphia. Among those paying their final respects were pallbearers Al Reach and Napoleon Lajoie, along with longtime baseball compatriots Dick McBride, Levi Meyerle, Charley Fulmer, and others. Philadelphia Phillies founder, sporting goods magnate, and former Athletics teammate Reach referred to Fergy as “reliability personified” and further eulogized, “He won his spurs in the days when it took iron courage to be a backstop. He had to catch without gloves, mask, or chest protector. He could dodge a foul tip faster than any man I ever saw.”94 Nick Young, former National League president and one-time teammate with the Washington Olympics, described Malone as “one of the greatest players of his day (or any other day). He was an earnest, hard worker, and as plucky a player as ever stood behind the bat.”95

The once-great catcher faded from public memory in the decades following his death. In August 2019, two vintage base ball clubs, the Diamond State Base Ball Club of Wilmington and the Athletic Base Ball Club of Philadelphia, along with several of Fergy Malone’s descendants, honored him with a memorial marker placed on his previously unmarked grave in celebration of the 175th anniversary of his birth and his enduring baseball legacy.96

Although Malone is all but forgotten by most modern American baseball fans, his legacy is recognized in his native land. Baseball Ireland’s Fergy Malone Batting Champion Award is given annually to its B League batting champion in recognition of Malone’s significant contributions to baseball.97

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the Delaware Historical Society for access to the Diamond State Base Ball Club’s scorebook and meeting minutes and use of Fergy Malone’s portrait.

This biography was reviewed by Matthew Albertson, Jeffrey Kabacinski, Bill Lamb, and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Larry DeFillipo.

Sources

In addition to the sources shown in the Notes, the author used Ancestry.com, Baseball-Almanac.com, Baseball-Reference.com, and FamilySearch.com.

Notes

1 “Fergy Malone,” Baseball-Reference.com, accessed July 8, 2025.

2 Alfred Henry Spink, The National Game (St. Louis: National Game Publishing Co., 1910), 92.

3 Same as above and “Athletic vs. Olympics,” Philadelphia City Item, June 22, 1871. The City Item game account indicates: “Malone’s catching was very fine. In playing close under the bat, he has no superior in America.”

4 “Old-Time Base Ball Stars,” Philadelphia Inquirer Magazine, May 18, 1902: 8.

5 Arthur Bartlett, Baseball and Mr. Spalding: The History and Romance of Baseball (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Young, Inc., 1951), 17 and William J. Ryczek, Blackguards and Red Stockings: A History of Baseball’s National Association, 1871–1875 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 1992), 20.

6 On May 20, 1871, Malone became the third Irish-born major leaguer when he debuted in the National Association, following Andy Leonard (who debuted on May 5, 1871) and Ed Duffy (May 8). Malone was the sixth Irish-born player in the National League upon his debut on May 23, 1876. He was preceded in the NL by Leonard and teammate Tim Murnane (both April 22, 1876), Jimmy Hallinan (April 25), Tommy Bond (April 27), and John McGuinness (May 6).

7 Fergy Malone, Baseball-Reference.com, accessed July 8, 2025.

8 Ireland, Catholic Parish Registers, 1655–1915, Ancestry.com (Provo, UT: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2016). A transcription of the original record for the Diocese of Armagh, Parish of Ballinderry indicates Fergy’s baptism date as August 27, 1843; however, Malone reported his birth as being August 1844 in the 1900 U.S. census, which is an age also consistent with his immigration record, the 1880 U.S. census, and his death certificate.

9 U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists, 1798–1962, Pennsylvania, Ancestry.com (Lehi, UT: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2006). The manifest for the ship Tonawanda from Liverpool, England landed in Philadelphia on August 31, 1852, and included passengers Rosanna Malone (age 42) and children Anthony (11), Sarah (10), Fergus (8), Mary (6), William (5), Eleanor (3), and an unnamed male child born August 10 during the journey.

10 “Old-Time Base Ball Stars,” Philadelphia Inquirer Magazine, May 18, 1902: 8.

11 “Athletic vs. Olympic,” New York Clipper, November 22, 1862: 253.

12 “Base Ball,” Philadelphia City Item, April 11, 1863.

13 “Base Ball,” Philadelphia City Item, August 1, 1863.

14 “Base Ball,” Philadelphia City Item, September 12, 1863; “Ball Play,” New York Clipper, September 19, 1863: 178; “Athletics to Altoona,” Philadelphia City Item, September 19, 1863; “Base Ball,” Philadelphia City Item, October 3, 1863; “Base Ball,” Philadelphia Sunday Mercury, October 4, 1863: 3; and “Base Ball,” Philadelphia City Item, October 10, 1863.

15 Pennsylvania Marriages, 1709-1940. Familysearch.com.

16 Ancestry.com. City directories for Philadelphia 1867–1904 show Fergy Malone living in the city of Philadelphia, except for: 1866/67, Wilmington, Delaware; 1869–1870, Washington, D.C.; and 1903–1904, Seattle, Washington. U.S. censuses for 1860, 1870, 1880, and 1900 show Malone as a Philadelphia resident.

17 “Base Ball,” New York Clipper, June 18, 1864: 79; “Nassau, of Princeton vs. Athletic, of Philadelphia,” New York Clipper, July 16, 1864: 108; “A Series of Grand Matches in Philadelphia,” New York Clipper, August 6, 1864: 131; “Base Ball,” Philadelphia City Item, June 25, 1864; “Athletics vs. Nassaus,” Philadelphia City Item, July 9, 1864; “Base Ball,” Philadelphia City Item, September 3, 1864; “Base Ball,” Philadelphia City Item, October 8, 1864; and “Base Ball Match – Atlantic, of Brooklyn, vs. Athletic, of Philadelphia,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 12, 1864: 8.

18 Samuel P. Bates, History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861–5, Vol. V (Harrisburg, PA: B. Singerly, 1871), 436–438 and 443. The regiment of “Hundred Day Men” was organized largely for garrison duty to augment existing Union manpower as a final push to bring the war to a close in 100 days. Malone and his Athletic teammates were all mustered in on July 16, 1864, and were mustered out with the entire company on November 17 of the same year. Dick McBride’s brother Frank served as captain of Malone’s division, Company A of the 196th.Regiment.

19 “The Athletic Club, of Philadelphia,” New York Clipper, May 13, 1865: 34.

20 During the 1865 season, Malone played 11 games at catcher, five at third base, two at first base, and one at pitcher for the Keystones. Additionally, he umpired at least five late-season games in games involving the Athletics and their guest opponents.

21 Marshall D. Wright, The National Association of Base Ball Players, 1857–1870 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2000), 110–113 and Peter Morris, But Didn’t We Have Fun? An Informal History of Baseball’s Pioneer Era, 1843–1870 (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2008), 147–150.

22 Delaware Historical Society (Wilmington, DE), Diamond State Base Ball Club Meeting Minutes, 1865–1866.

23 John Freyer and Mark Rucker, ed., Peverelly’s National Game (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2005), 120.

24 “For the Delaware Republican,” Delaware Republican, July 19, 1866: 3. Malone indicated he was a member of the Keystone Club of Philadelphia until March 1866.

25 Peter Morris, A Game of Inches: The Story Behind the Innovations That Shaped Baseball (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2010), 463–464 and Morris, But Didn’t We Have Fun?, 169–172.

26 Wilmington General and Business Directory, 1866 –67 (Wilmington: Boughman, Thomas & Co., 1866), 116 and “Base Ball,” (Wilmington) Delaware State Journal and Statesman, July 10, 1866: 3. The fact that Malone’s shop was nicknamed “the Diamond State Cigar Store” may serve as a coy implication that the baseball club’s organizers had involvement with financing the business, as Fergy had no apparent means to do so on his own. Perhaps not coincidentally, the supposed business arrangement between the Diamond States and Malone was strikingly like the deal the Athletic Club of Philadelphia employed to recruit Al Reach from the Eckfords of Brooklyn one season prior, as referenced in Morris, But Didn’t We Have Fun?, 178.

27 Boyd’s Wilmington (Delaware) Directory for 1865–66 (Wilmington: Boughman, Thomas & Co.), 193. John Malone removed to Wilmington about 1865. He was involved in the marble business and, by 1872, owned and operated his own marble, granite, and stone works business, coincidentally located just four blocks east of the Diamond State’s original home ball field.

28 Doug Gelbert, The Great(er) Delaware Sports Book: Second Edition (Hendersonville, NC: Crudent Bay Books, 2016), 100.

29 Delaware Historical Society (Wilmington, DE), Diamond State Base Ball Club Scorebook, 1865–1867. The Diamond States’ only two losses came at the hands to two Pennsylvania clubs, the Brandywine Base Ball Club of West Chester and the Keystones Base Ball Club of Philadelphia.

30 Delaware Republican sources: “Diamond State vs. Atlas,” June 11, 1866: 2; “For the Delaware Republican,” June 18, 1866: 2; “Atlas Base Ball Club,” June 18, 1866: 3; “Base Ball.” July 12, 1866: 3; “For the Delaware Republican,” July 19, 1866: 3; and “To the Diamond State Base Ball Club of Wilmington,” July 30, 1866: 1. The Atlas Club’s contention that Malone was an active member of the Athletics appears to have been based on either a misunderstanding of the facts or, at worst, a display of petty resentment. While Malone may have never submitted a letter of resignation to the Athletics after the 1864 season, he joined the Keystone Club in March 1865 and even played uncontested matches against the Athletics that season. Based on testimony by both Malone and the Athletics’ president at the time, Thomas Fitzgerald, Fergy contemplated rejoining the Athletics in 1866 and, indeed, participated in pre-season practice games with the club. He never actually joined the Athletics before resigning from the Keystones in March 1866. Presumably, Malone did not sign with Diamond State until just before playing his first game with the club on May 31—beyond the 30-day waiting period required by NABBP rules.

31 “Old Time Base Ball,” Philadelphia Inquirer Magazine, May 18, 1902: 8.

32 John Shiffert, Base Ball in Philadelphia: A History of the Early Game, 1831–1900 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2006), 52–54.

33 Wright, 145 and “Keystone vs. Artic,” Philadelphia City Item, June 29, 1867. Most of the Quakers’ wins came against competitively weaker, local opponents, rather than national-class clubs.

34 “Our National Game,” Philadelphia City Item, July 6, 1867.

35 Peter Morris, et al., Base Ball Pioneers, 1850–1870: The Clubs and Players Who Spread the Sport Nationwide (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2012), 265; U.S. Register of Civil, Military, and Naval Services, 1863–1959, Ancestry.com (Provo, UT: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014); and “‘Uncle Nick’ Young Pays Splendid Tribute to Fergy Malone as Man and Player,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 23, 1905: 10. Nick Young confirmed that, as a member of the Olympic Base Ball Club of Washington, he was dispatched by club officers to Philadelphia to secure Fergy Malone’s services. He finalized the deal after handing Malone a $20 bill and guaranteeing a job at the U.S. Treasury Department.

36 Wright, 200–201.

37 Thomas Gilbert, How Baseball Happened: Outrageous Lies Exposed! The True Story Revealed (Boston: David R. Godine, 2020), 314–316. According to Gilbert, “Dick Hurley and Waddy Beach were other players recruited by the lure of Treasury Department clerkships.”

38 The Olympics 1869 roster included Bob Reach (formerly of the Keystone Base Ball Club), Dick Hurley (from the Buckeye Base Ball Club of Cincinnati), a pair of former Washington clubbers, M.E. Urell (from the Union Base Ball Club), and Sam Yeatman (from the Jefferson Base Ball Club).

39 Ryan A. Swanson, When Baseball Went White: Reconstruction, Reconciliation, & Dreams of a National Pastime (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014), 108–112 and “Base Ball,” Daily Morning Chronicle (Washington), September 21, 1869: 4 and “Base Ball,” Daily Morning Chronicle (Washington), October 13, 1869: 4. When the Olympics accepted challenges from and played games against two black Washington ball clubs, it marked the first time in baseball history that a professional white club had done so. On September 20, the Olympics’ regular starting nine with Malone at catcher, coasted to an uneventful 56–4 home victory over the Alert Base Ball Club. Although the gentlemanly match came off without a hitch, a few days later, one of the Olympics’ main rivals, the Maryland Base Ball Club of Baltimore, announced they would not play future games against the Olympics because of their “match with a colored club.” The Olympics proceeded to host a second black club from the District, the Mutual Base Ball Club, on October 12. Without Malone and three other starters in the lineup, the Olympics held off their opponents in an eight-inning match, 24–15. These two games with the Alerts and Mutuals were made more significant by the fact that the NABBP, of which the Olympics were a member, denied black clubs’ admittance to their organization.

40 Wright, 248–249 and Morris, Base Ball Pioneers, 266.

41 “Sporting Matters,” Washington Capital, March 23, 1879: 7. According to baseball rules of 1868 and 1869, foul balls caught on a single bound were counted as outs. The foul bound rule persisted until it was eliminated by the National League in 1883—the following year by the American Association.

42 Shiffert, 68.

43 Spink, 92.

44 Wright, 295-295. Malone also led the Athletics in hits against pro clubs (86), edging out teammate Wes Fisler by one hit.

45 John Thorn, Baseball in the Garden of Eden: The Secret History of the Early Game (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011), 148–151.

46 Shiffert, 75.

47 “1871 Philadelphia Athletics Statistics,” Baseball-Reference.com, accessed July 8, 2025. These statistics are only for championship games against other NA teams and exclude numerous exhibition games vs. NA teams and games against amateur clubs.

48 “Athletic vs. Eckford,” New York Clipper, May 20, 1871:52 and “Base Ball. The Professionals of 1871,” New York Clipper, October 28, 1871:236.

49 Shiffert, 76.

50 “1872 Philadelphia Athletics Statistics,” Baseball-Reference.com, accessed July 8, 2025.

51 Shiffert, 78. Shiffert incorrectly states that Jimmy Wood joined the Philadelphias in July 1873; however, multiple sources show the correct date as May 1873, including the “The Mutual vs. Philadelphia,” Brooklyn Daily Times, May 20, 1873:3.

52 David Nemec, The Great Encyclopedia of Nineteenth Century Major League Baseball, Second Edition (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2006), 56, and “1873 Philadelphia Whites Statistics,” Baseball-Reference.com, accessed July 8, 2025.

53 “Miscellaneous,” Philadelphia Sunday Republic, November 2, 1873, and Michael Haupert, “MLB’s Annual Salary Leaders Since 1874,” SABR.org, accessed July 8, 2025.

54 Nemec, 67.

55 Nemec, 73 and “1874 Chicago White Stockings Statistics,” Baseball-Reference.com, accessed July 8, 2025. In 1874, Malone placed third in putouts (193) and second in assists (58) among NA catchers.

56 “1874 National Association Team Statistics,” Baseball-Reference.com, accessed July 8, 2025. Malone was the ninth eldest player among regular NA starters by end of the 1874 season.

57 “1875 Philadelphia Whites Statistics,” BaseballReference.com, accessed July 8, 2025.

58 Shiffert, 89-91, and “Sport and Pastimes,” Philadelphia Sunday Mercury, July 23, 1876: 3. The Pearls permanently disbanded in July 1876.

59 “Base Ball,” St. Louis Dispatch, January 22, 1876:2.

60 Philadelphia Times: “The Athletic Club,” June 13, 1876: 2; “A Game at Last,” June 15, 1876: 4; and “Still Another Game,” June 16, 1876: 4.

61 Nemec, 125.

62 Shiffert, 95-96.

63 “1877 National League Team Statistics,” Baseball-Reference.com, accessed July 8, 2025. The average age of National League catchers in 1877 was twenty-five years old. Malone turned thirty-three in August of that season.

64 Shiffert, 144 and “Our National Game,” Philadelphia City Item, May 22, 1877. Shiffert incorrectly identifies McMullin as the initial manager of Philadelphia BASE BALL CLUB, when it was instead Malone. The City Item identifies Charles Spering, Esq. as the club’s first president, with Malone and Tom Pratt serving as its only directors.

65 “The New Philadelphia Club,” Chicago Tribune, April 22, 1877: 7 and “Notes of the Game,” Philadelphia Times, May 7, 1877: 4.

66 “The National Game,” Philadelphia Times, May 14, 1877: 3; “Base Ball,” Philadelphia Times, May 18, 1877: 4; “Philadelphia’s Defeat,” Philadelphia City Item, May 23, 1877; “Base Ball Playing,” Philadelphia Times, May 28, 1877: 4; “The National Game,” Philadelphia Times, May 29, 1877: 4; and “The Phenomenal Club,” Philadelphia City Item, June 2, 1877.

67 “National Game,” Philadelphia Times, May 14, 1877: 3; “The Diamond Field,” Philadelphia Times, June 6, 1877: 3, and “General Notes,” Louisville Courier Journal, June 8, 1877: 4.

68 “Base Ball,” Philadelphia Times, May 18, 1877: 4; “Philadelphia’s Defeat,” Philadelphia City Item, May 23, 1877; “Summer Sports,” Philadelphia Times, May 28, 1877: 4; “The National Game,” Philadelphia Times, May 29, 1877: 4; and “The Phenomenal Club,” Philadelphia City Item, June 2, 1877.

69 “Local Summary,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 6, 1877: 2, “The New Organization,” Philadelphia City Item, June 6, 1877; and “The Diamond Field,” Philadelphia Times, June 6, 1877: 3. Malone and McMullin did not appear to have a contentious history prior to the 1877 conflagration. The two were teammates on the 1875 Philadelphia White Stockings, and that relationship is likely why Malone recruited McMullin to join his 1877 club.

70 “Fergy On His Mettle,” Philadelphia City Item, June 6, 1877, and “Ball Club Feuds,” Philadelphia Times, June 8, 1877: 1.

71 “The City and Suburbs,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 30, 1877: 3 and “Gossip,” Philadelphia Sunday Republic, August 5, 1877.

72 “Diamond Chips,” St. Louis Spirit, May 4, 1878: 3 and “Base Ball,” St. Louis Evening Star, April 26, 1879: 2.

73 “The National Clubs,” Boston Post, March 10, 1879: 3 and “Sporting Matters,” Boston Globe, April 8, 1879: 2.

74 New York Clipper: “Base Ball,” April 19, 1879: 27; “Base Ball,” April 26, 1879: 36; “Base Ball,” May 3, 1879: 43–44; and “Base Ball,” May 10, 1879: 50 and 53.

75 “Notes of the Game,” Chicago Tribune, May 11, 1879: 7.

76 “Short Stops,” Oakland Tribune, May 27, 1879: 3.

77 Philadelphia Times: “The National Game,” May 17, 1879: 4 and “Defiance vs. West Philadelphia,” June 27, 1879: 4.

78 “A Six-Inning Game,” Philadelphia Times, June 28, 1879: 4.

79 “A New Base Ball Team,” Philadelphia Times, June 22, 1879: 3 and “Devlin Reinstated,” Philadelphia Times, June 29, 1879: 3. Malone was a leader in an early petition effort among Philadelphia’s baseball community for Jim Devlin’s reinstatement back into professional baseball. In 1877, National League president William Hulbert issued a lifetime ban on Devlin and three of his teammates in 1877 accused of throwing games for money. The Philadelphia petition and other appeals had no impact, as the NL never lifted the ban on Devlin and his three teammates.

80 “Notes of the Game,” Chicago Tribune, July 20, 1879: 6 and “Baseball Notes,” New York Clipper, July 19, 1879: 133.

81 Philadelphia city directories, 1878 – 1883.

82 “Tips. Local and Elsewhere,” St. Louis Daily Globe-Democrat, December 13, 1881: 8 and “Sporting Matters,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 14, 1882: 2.

83 “Around the Bags,” Camden (New Jersey) Daily Courier, September 13, 1882: 1.

84Jon Springer, Once Upon a Team: The Epic Rise and Historic Fall of Baseball’s Wilmington Quicksteps (Wilmington, DE: Sports Publishing, Inc., 2018), 18-22 and “Base Ball Matters,” Wilmington (Delaware) Morning News, August 10, 1883: 1.

85 “Work of a Ball Nine,” Wilmington Morning News, October 5, 1883: 4.

86 “The New Union Association Making Inroads into the League,” Philadelphia Times, November 11, 1883: 6. Tom Pratt was not only president and chief financier of the Keystones; he was also vice-president of the Union Association (UA). The new league served to challenge the National League and American Association’s reserve rule by competing with them for players and signing those previously banned by those two leagues. According to Shiffert, the fact that the UA needed an influx of players, particularly those who would attract ticket buyers, probably accounts for Pratt’s signing two long-past-their-prime hometown favorites like Fergy Malone and Levi Meyerle.

87 “What the Eastern League Did at Yesterday’s Meeting,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 8, 1884: 3; Shiffert, 236; and “Fergy Malone,” Baseball-Reference.com, accessed July 8, 2025.

88 “Base Ball,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 18, 1884: 2. The game account notes: “Malone was weak behind the bat, and [pitcher] Weaver was compelled to slow up in his delivery.”

89 Eddie Mitchell, Baseball Rowdies of the 19th Century: Brawlers, Drinkers, Pranksters and Cheats in the Early Days of the Major Leagues (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2018), 185–186, “National League,” Philadelphia Times, May 26, 1892: 2, and “Fergy Malone Umpire Stats,” Baseball-Almanac.com, accessed July 8, 2025. Fergy Malone was a fill-in umpire for a National League game on April 7, 1888, between Baltimore and Philadelphia.

90 “State Association Record,” Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Evening Leader, July 16, 1887, 4 and “State League Collapses,” Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Sunday Leader, July 17, 1887, 1. Malone likely left Williamsport because the club and the entire PSABBC were on shaky ground. Two of the league’s strongest clubs, Scranton and Wilkes-Barre left the PSABBC for the International Association (on June 6 and July 16 respectively). Allentown also announced their departure on July 16. The PSABBC collapsed after Williamsport disbanded on July 16, less than a week after losing Malone and two players. “Chris Was Fired and Fergy Hired,” Scranton (Pennsylvania) Tribune, July 29, 1887: 3; “The Championship Record,” New York Clipper, August 6, 1887, 330; and “The Championship Record,” New York Clipper, October 8, 1887, 478.

91 “The Allentown Club Hustling for a Big Scheme,” Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Times-Leader, January 3, 1888: 4.

92 “The Championship Record,” Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Evening Leader, May 24, 1888, 1 and “Stray Sparks from the Diamond,” New York Clipper, May 26, 1888, 174.

93 Ancestry.com: City directories for Philadelphia and Seattle, and Official Register of the United States, Containing a List of the Officers and Employees in the Civil Military (for the years 1891–1904.)

94 “Philadelphia Points,” Sporting Life, February 11, 1905: 2.

95 “‘Uncle Nick’ Young Pays Splendid Tribute to Fergy Malone as Man and Player,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 23, 1905: 10.

96 Chris Barrish, “Vintage Baseball Clubs from Philadelphia and Delaware Team Up to Honor 1800s Star with Gravestone,” August 17, 2019, WHYY.org, accessed July 9, 2025.

97 Baseball Ireland, “Baseball Ireland Awards 2021,” Spring 2022 Newsletter: 4, accessed July 8, 2025.

Full Name

Fergus G. Malone

Born

August , 1844 at County Tyrone, Tyrone (Ireland)

Died

January 18, 1905 at Seattle, WA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.