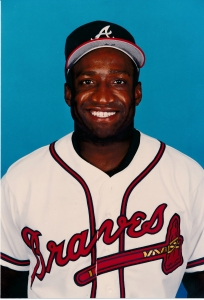

Mike Devereaux

“You dream of things like this, but you never think of it happening to you. It’s something out of the movies.” — Mike Devereaux, October 15, 1995, after being named NLCS MVP1

“You dream of things like this, but you never think of it happening to you. It’s something out of the movies.” — Mike Devereaux, October 15, 1995, after being named NLCS MVP1

Mike Devereaux became an instant hero on an Atlanta Braves team filled with future Hall of Famers. Having played with five different teams in a major-league career spanning 12 years, Devereaux’s most prestigious career highlight came in October 1995 when he was named the Most Valuable Player of the National League Championship Series. The Braves had acquired the veteran outfielder in late August as an added insurance measure for their pennant drive. Devereaux not only provided the game-winning hit in extra innings in Game One of the NLCS against the Cincinnati Reds, but his three-run homer in Game Four was the capstone that propelled the Braves back to the World Series for the third time in five seasons, one that they won.

Born on April 10, 1963, in Casper, Wyoming, Michael Devereaux was the youngest of four children born to Fred and Mary Devereaux. Fred was an electrical engineer by profession and Mary a part-time schoolteacher. Mike, following after the births of his sister, Phreda, and brothers, Fred Jr. and Ron, took a shine to baseball early. The three Devereaux brothers all played Little League, Babe Ruth, and American Legion baseball, and because they were all born a year apart, for two seasons they played on the same team. When school was in session, however, the Devereaux household focused equally on education. There was no television viewing until all homework was completed, and on school nights, the kids had to adhere to established bedtimes. And weekend nights carried a curfew.

But make no mistake about it. Baseball became something of an obsession for Devereaux. He became an avid fan of the Oakland A’s during their run of three consecutive World Series championships in the early 1970s, and especially of their star, Reggie Jackson. Meanwhile, Fred Devereaux, president of the local Little League, was able to coax a number of big-league ballplayers to come to Casper to speak with the kids, among them Gaylord Perry, Johnny Bench, Pete Rose, and Reggie Jackson.2 Devereaux’s interest in the game continued to grow, especially in his early teenage years. His father, who would serve as Mike’s coach until he was 16, encouraged his youngest son to pursue his passion and take it as far as he could. Devereaux later recalled, “When I was 13, 14, and 15, I was in Babe Ruth and I realized that I loved the game more than anything else. I couldn’t wait to go to school and play afterwards.”3

Devereaux attended Casper’s Kelly Walsh High School, but it had no formal baseball program. That proved to be no deterrent. He donned a uniform for the Casper Oilers each summer to play American Legion ball; his first year he played in multiple positions, including shortstop, pitcher, and outfielder, while brothers Fred typically pitched and Ron caught. The brothers helped lead the Oilers to three consecutive American Legion state titles.

For three successive years, each one of the Devereaux brothers at age 18 in turn was named MVP in American Legion Baseball for the state for that season. Mike became a standout player on Kelly Walsh’s teams in basketball, football, and track and field, and was named All-State, helping his high school win state championships in his senior year. In track and field competition, his athleticism allowed him to establish new state records in the 100-meter, 200-meter, and 400-meter dashes, and the high jump. In fact, it was for these sporting achievements away from the baseball field that he was inducted into the National High School Hall of Fame in 2014, and all his college scholarship offers were for football. But baseball was his favorite sport, and he was determined to play it.4

After his high school graduation in June 1981, Devereaux enrolled at Mesa Community College in Arizona, where he joined his brother Ron on the Thunderbirds baseball squad, playing outfield. The team took third in the National Junior College World Series in June 1982.5 While Mike was at Mesa, a teammate, shortstop Steve Murray, called him Devo, a nickname that stuck. At season’s end, Devereaux was selected as the team’s MVP and named First Team All-Conference.6

The star athlete accepted a scholarship from perennial baseball powerhouse Arizona State University in nearby Tempe for his junior and senior college years, 1984 and 1985. He played right field. In 1984, Devereaux was joined in the outfield by future big leaguers Barry Bonds in center and Oddibe McDowell in left. Has there ever been a better college outfield? Devereaux homered in his first game as a Sun Devil, the team going on to reach the College World Series in 1984. Devereaux launched a go-ahead homer in the seventh inning of the first game of the CWS, and went 3-for-7 in the tournament, though Cal State Fullerton won the national championship. ASU finished the 1984 season with a 55-20 record.7 The Cleveland Indians selected Devereaux in the 26th round of the June 1984 amateur draft, picking him in a low round likely because he was scheduled to have major reconstructive knee surgery.8 He elected not to sign, continued pursuit of his degree, and played outfield for ASU a second season, batting .296, including a noteworthy season opener against UC Santa Barbara, in which he collected four doubles, tying a university record.9

Several months later, just as he was graduating with his bachelor of science degree in finance, the Los Angeles Dodgers selected Devereaux in the fifth round of the June 1985 draft. He signed his first professional contract with Dodgers scout Dennis Haren. He was assigned to play outfield with their rookie-league team in Great Falls, Montana, in the Pioneer League, managed by Kevin Kennedy, where in 70 games his offensive talents became apparent. Devereaux was named the league’s Player of the Year, batting a robust .356 and leading the league in runs (73), hits (103), RBIs (67), total bases (152), and stolen bases (40), helping the team compile an impressive 54-16 (.771) record. The organization then sent him to the Arizona Instructional League, where he played in 28 games.10

For the 1986 season, the Dodgers had Devereaux jump over both their low and high Class-A farm teams and placed him with the Double-A San Antonio Dodgers, in the Texas League. In 115 games with San Antonio, the right-hander batted .302 and collected 10 home runs, 53 RBIs, and 31 stolen bases. He returned to the team in 1987 and led the league in a number of categories, including at-bats (562) and games (135), while belting 26 home runs and batting .301. He also demonstrated a flair with the glove, his speed providing for several spectacular running catches. Devereaux led outfielders with 349 total chances in 1987, and he carried a league-best .991 fielding average. He was named to the league All-Star team and was voted San Antonio’s Player of the Year.11

Devereaux played outfield in three games at the end of the season for the Triple-A Albuquerque Dukes of the Pacific Coast League, and while there received a surprise call from Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda asking him if he was ready to come up to “The Show.” The next day, September 2, 1987, at age 24, he was in the starting lineup to make his major-league debut, playing right field in Dodger Stadium. Devereaux had never even been to a major-league ballpark. “I swung at the very first pitch I saw and got a hit,” he said. “So [laughing] I got that out of the way.”12 His single off the Philadelphia Phillies’ Don Carman was the first of nearly 1,000 hits he would accumulate in his big-league career.

In 19 games with the Dodgers in September, Devereaux played all three outfield positions. He went 12-for-54, batting .222, but had two three-hit games and a game-winning RBI. In the fall, just as he had the previous year, he played in the Arizona Instructional League, where he hit near .400. In three consecutive offseasons, from November to January Devereaux continued to hone his skills, playing for Santurce, San Juan, in the Puerto Rican Winter League, which had a professional working agreement with the Dodgers. Jay Bell and Rubén Sierra were among his teammates.13

Given his early success in the minors, Devereaux was hopeful of landing a spot on the Dodgers 1988 major-league roster, and thought he enhanced his chances after batting .414 in spring-training exhibition games in the Grapefruit League. But the competition was fierce. In the offseason between 1987 and 1988, the Dodgers had added veteran outfielders Kirk Gibson and Mike Davis, who joined regular starters John Shelby and Mike Marshall. Los Angeles brought Devereaux up in April to play center field to replace an injured Shelby; he started in four games but batted only .115 before being optioned back to Albuquerque, where he continued to excel. Playing in 109 games, Devereaux sported a .340 batting average in 423 plate appearances and finished fourth in the PCL in batting.

For a second consecutive year he was part of the September call-up. At the time, the Dodgers were in a tight race in the Western Division, and he was not expected to see much playing time. Devereaux was in the starting lineup for only one game, with 43 at-bats in 30 games, and could not get enough plate appearances to gain any traction, batting just .116. On September 21 against the San Diego Padres, Devereaux was inserted into a second game of a doubleheader as a pinch-runner, and two innings later, drove in the winning run with a walk-off single to bring the Dodgers one win closer to a division title. A week later, he was linked to a notable game in Dodgers annals. On September 28 Devereaux entered a game against San Diego as part of a double switch for Orel Hershiser after the Dodgers starter had completed the 10th inning to give him the major-league consecutive scoreless inning record. The Dodgers, however, left Devereaux off their postseason roster, a team that went on to defeat the Oakland A’s in the 1988 World Series.

In his four minor-league seasons with the Dodgers, Devereaux collectively batted .320 (549 hits in 1,716 at-bats) and averaged 35 steals a year. As the Dodgers looked ahead to the 1989 season, they already had a crowded outfield, and, moreover, their 1985 first-round draft pick, outfielder Chris Gwynn, was waiting in the wings. Trade speculation involving Devereaux began when the Dodgers were negotiating a swap with the Baltimore Orioles that resulted in the acquisition of first baseman Eddie Murray on December 4, 1988, for Brian Holton, Ken Howell, and Juan Bell. Still, the Orioles and Dodgers continued discussions and Devereaux’s name was among those mentioned in the swirling rumors. On March 12, 1989, in the midst of both team’s spring-training schedules, the Dodgers traded Devereaux to the Orioles for pitcher Mike Morgan.14 When asked his opinion of the transaction at the time, manager Lasorda remarked, “It’s hard to give up a person of the caliber of Mike Devereaux. Sometimes you have to trade guys you think the world of.”15

What kind of team would Devereaux be joining? Though the Orioles dropped 107 games in 1988, including a record 21 consecutive losses to open a season, he reacted favorably when he learned of the swap. “It takes a big load off my mind,” Devereaux told the Los Angeles Times. “Now that this is over, I can concentrate on baseball. I’d like to be playing in LA, but I just want to be playing in the major leagues.”16 He explained that he felt no ill will toward the Dodgers and respected their decision for trading him, allowing them to fill their pitching needs while at the same time providing him an opportunity to play on a big-league ballclub.17

In 1989, his debut season with Baltimore, Devereaux had a key role as both an outfielder and a designated hitter. Standing an even 6 feet tall and weighing 195 pounds, the right-hander swung a distinctive black bat which, he said, made it difficult for rival outfielders to get a jump on the batted ball based on his own observations peering in from the outfield.18 He had a good rookie season by all measures, batting .266, stealing 22 bases, and playing in 122 games. There were several highlights in his inaugural year. These include his first big-league home run, on April 21, against the Minnesota Twins’ Allan Anderson, and a four-hit game against the Milwaukee Brewers on June 8.

In one memorable game, on July 15, in a jam-packed Memorial Stadium, he became the first Orioles rookie since Cal Ripken Jr. in 1982 to hit a walk-off home run when he launched a pitch from the Angels’ Bob McClure that wrapped around the left-field foul pole, producing a thrilling come-from-behind 11-9 win. The Angels vociferously protested that the ball had been foul, but the umpire stood firm. Three weeks later, on August 6, Devereaux hit another walk-off homer, against the Texas Rangers’ Jeff Russell, in a 3-2 win. Another signature moment occurred in a late-season game when Nolan Ryan intentionally walked a batter in order to face Devereaux – only to have the rookie blast a three-run home run off the future Hall of Famer.

Surprisingly, given their dismal record in the preceding season, the Orioles, managed by Frank Robinson, played inspired baseball all summer long and the rookie Devereaux played a key role in what became known as the “Why Not?” team’s magical run. Baltimore led the American League East Division for most of the summer and fell just shy of making the postseason, finishing second, two games behind the Toronto Blue Jays. “We were right there until the end and it was just heartbreaking to come up short,” Devereaux said in 2009.19 Still later, looking back on that season from the vantage point of three decades, he said, “It was going to be an incredible season either way but it would have just been just icing on the cake to have been able to bring a championship back to Baltimore with all the support we had here.” Devereaux added, “We didn’t even win it and we got a parade. … Pretty cool”20

In 1990 the Orioles regressed as a team, finishing fifth in the AL East. Platooning again, Devereaux saw his season average dip to .240, primarily due to getting off to a poor start in the first six weeks of the season. Things greatly improved afterward; he was named American League Player of the Week in late July, when he batted over .420, with two doubles, a triple, and three home runs, including the first of his three career grand slams, and followed the next night with an eighth-inning homer that broke up a no-hitter being hurled by the Tigers’ Jeff Robinson.

In 1991 Devereaux finally got his chance to be the everyday starting center fielder after the Orioles traded Steve Finley to the Houston Astros. In addition to his solid defense, Devereaux hit .260, contributing 19 home runs and driving in 59 runs in 608 at-bats. He became only the second Oriole to get 10 or more doubles, triples, home runs, and stolen bases; Phil Bradley had been the first. Still, the season was not a stellar one in the annals of the franchise; the Orioles finished a distant 24 games behind Toronto. Reflecting back to this period after he had retired, Devereaux remarked that after experiencing firsthand the team’s thrilling highs of his rookie year, the 1990 and 1991 campaigns were especially disappointing. But even losing taught both baseball and life lessons, and Devereaux felt thankful that Frank Robinson was in his corner, though he was not one to sugarcoat things. He said that sometimes after he struck out and was heading back to the dugout he would see the clearly disappointed manager just shaking his head.21

The team departed venerable Memorial Stadium for Oriole Park at Camden Yards in 1992. Not only did Devereaux permanently etch his name into the record books when he became the first Oriole to hit a home run in the new ballpark when he did so against Cleveland’s Jack Armstrong on April 9, but in his new surroundings he experienced the best season of his major-league career. He appeared to benefit from a shift in the batting order, being moved from first to hitting second in the lineup; in addition to clubbing 24 home runs, and speeding to third on 11 triples, Devereaux amassed 107 RBIs, 37 of them either game-tying or go-ahead runs. With the bases loaded, he went 13-for-25, a .520 clip.

Moreover, beyond his clutch hitting, Orioles fans appreciated Devereaux’s dramatic center-field play in which he frequently robbed opposing teams of hits, including some that were otherwise destined to go over the fence. One such spectacular play, a ball snatched from the stands that would have resulted in a three-run home run by the Blue Jays’ Joe Carter on June 5, 1992, was aptly described by Thomas Boswell in the Washington Post the following day: “Devo took his life in his hands. He didn’t leap straight up. He didn’t have time. He launched himself at what looked like a 45-degree angle, his legs jack-knifed across each other. His right cheek smashed into the very top of the wall just as his arm shot into the second row of seats. How the ball found the glove, no one will ever know.”22

At season’s end Baltimore’s baseball beat writers and broadcasters voted Devereaux the winner of the Louis M. Hatter Most Valuable Orioles Award, a year in which the outfielder led the team in 10 offensive categories. He finished seventh in votes for the AL MVP, and was named to The Sporting News AL all-star team. “It all came together that year,” Devereaux said. “I batted second and with Cal [Ripken] hitting behind me, I got all those good pitches.”23

While the center fielder batted a steady .250 in 1993, and missed nearly a month of play with a stint on the DL due to a shoulder injury and sore heel, it was the 1994 season in particular he would have liked to have erased. After hitting a home run and triple earlier in a game on May 8, 1994, in front of over 47,000 hometown fans, Devereaux was nailed on the cheek by a rising fastball thrown by the Indians’ Chad Ogea on May 8. It was a game featured on ESPN’s Sunday Night Baseball and later discussed by broadcaster Jon Miller, who was behind the mic for the game, in his book, Confessions of a Baseball Purist. Though Devo did not miss much playing time from the errant pitch, he was placed on the DL for two weeks in June with a pulled right hamstring, and he never fully regained his form. When the season was shut down after the players struck in August, Devereaux was hitting barely above .200. His time with Baltimore was drawing to a close, with his contract about to expire and the club making it clear it intended to look in a new direction.24

Devereaux filed for free agency in October 1994, and inked a one-year contract with the Chicago White Sox on April 8, 1995, just as the strike ended. He played exceptionally well for the White Sox as their everyday right fielder. He enjoyed playing on the South Side, and was having a banner year. In 333 at-bats, Devereaux collected 102 hits and was batting .306. Five days before the September 1 trading deadline, Devereaux went to the Atlanta Braves in a straight-up exchange for minor-league outfield prospect Andre King.25

Braves outfielder Ryan Klesko was enjoying a good season, but he had just turned 24 that summer. John Schuerholz, Atlanta’s general manager, sought to add a veteran right-handed hitter and a solid defensive presence to their roster for their latest pennant drive. Devereaux was pleased with the trade. Though he had fun playing with Chicago, the White Sox were well under .500 and struggling mightily in the standings, and he would now be playing for a team that habitually made it into the postseason, and at the time of the transaction had a double-digit lead over the second-place Phillies for the East Division title. Moreover, just six months earlier, Devereaux had decided to buy property in the Atlanta suburbs to build his dream house. In fact, because he had earlier told teammates of his impending residency shift to Georgia, when informed of the trade, Devereaux initially thought his manager, Terry Bevington, was pulling a prank on him.

His trade to Atlanta resulted in reduced playing time during the remainder of the regular season, with most of his appearances coming in as a defensive replacement in late innings, or stepping up to the plate as a pinch-hitter and staying in the game. Devereaux had just 55 plate appearances, batting .255. His most significant contributions to the Atlanta team, however, were yet to come with his first opportunity to play in the postseason.26

In Game One of the 1995 NLCS, on October 10, hosted by the Cincinnati Reds, the Braves and Reds were in a tight pitching duel that had gone into extra innings. With the game knotted 1-1 in the 11th inning, Devereaux’s line-drive single drove in Fred McGriff in an important win on the road. Even after getting the clutch game-winning hit, however, few gave much thought to his role going forward in the series. That is, until manager Bobby Cox penciled in Devereaux to start Game Four on October 14 in place of right fielder David Justice, who had been sidelined after being hit by a ball during batting practice before the game.

“It was funny how some things work out and being in the right place at the right time,” Devereaux said in 2019 about that opportunity to be in the lineup.27 In the seventh inning, Devereaux delivered the decisive blow, muscling a three-run home run against the Reds bullpen ace, Mike Jackson, as the Braves swept aside the Reds in four games. “It’s a feeling I never believed I could have,” he said after receiving the NLCS MVP Award for his key hits, batting .308, and driving in five runs. “It’s a lot of fun. I’m definitely going to enjoy the moment.”28

Devereaux appeared in five of the six World Series games against the Indians, in a platooning role. He went up to the plate six times, and got on base three times, with a hit and two walks, batting .250. Devereaux was patrolling the outfield and was on the field to joyously celebrate with his teammates when Marquis Grissom snared the ball for the final out in Game Six to give the Braves their first World Series championship since 1957. The Braves did not figure Devo to be in the club’s long-term plans, however, and he was granted free agency after the season.

Always a crowd favorite, Devereaux returned home to Baltimore the following season, signing a one-year contract on January 11, 1996. He was sorry not to have been present the prior year when Cal Ripken broke the consecutive-game streak set by Lou Gehrig (though he watched the historic game on ESPN like much of America). He hoped that with smart defensive play in the Camden Yards outfield with which he was so familiar and by putting up good offensive numbers on the other side of the ledger, he would have a fair chance to be an everyday starting outfielder, which he had been as recently as the preceding year with the White Sox.

The new Orioles manager, Davey Johnson, who had just come over from managing the Reds, however, told Devereaux he thought he had always been a player who had come off the bench throughout his career. That had not been the case, of course, since his earliest days in Memorial Stadium, until he got to Atlanta. Which, in essence, ultimately proved to be a trade-off. Devereaux would not have received the NLCS MVP Award or the World Series championship ring had he not suited up with the Braves, but he would end up paying a steep price. His image now had been reshaped to one as a platoon player, a narrative created just in his short six-week stint with the Braves.29 “It’s tough to sit on the bench and then go in and out of the lineup,” a frustrated Devereaux told the Baltimore Sun near the midway point of the season. “It’s something I am not accustomed to.”30

With reduced playing time, coupled with a nagging shoulder injury, Devereaux’s batting average tumbled to .229, though he hit .421 coming off the bench, frequently in key situations. He contributed defensively, including making seven outfield assists. The Orioles had a successful season in 1996, winning a wild-card spot and going on to defeat the heavily favored Indians three games to one in a best-of-five AL Division Series; Devo had an appearance in all the games. Baltimore advanced to face New York in the AL Championship Series, and were defeated four games to one. Devereaux had only a few at-bats in the two combined playoff series, and coming in as a late-inning defensive replacement in the outfield and pinch-runner. He was granted free agency after the season.

Devereaux signed a one-year contract with the Texas Rangers on January 6, 1997, but things did not work out well that season. Though his defensive play in the outfield was flawless, he got off to a slow start offensively, due in part to incurring a strained hamstring in April. He had stepped up to the plate only 80 times over a span of 29 games when he was released in June. He still believed he could play baseball at a big-league level and contribute his skills to help a team win, and to stay active, he signed on to play for a team in Venezuela for three months.

Coming full circle, Devereaux rejoined his original signing team, the Dodgers, agreeing to a contract on January 16, 1998. Devo was well aware he would be competing for one of the team’s coveted outfield spots, but he thought it was worth the gamble. The Dodgers had a number of younger outfield prospects they were looking to promote, but he thought they also may have had a desire to add a veteran to the club mix. Devereaux did all that was asked of him, showed hustle in spring training and made the roster as the season opened. In limited plate appearances in April, he was hitting over .300 but was nonetheless released in the first week of May to make room for their highly-touted rookie Paul Konerko, then coming off the DL.

Now 35 years old, Devereaux signed with the San Diego Padres organization a month later. He reported to their Triple-A team in Las Vegas, where he was playing regularly and was in the wings hoping to get called up, but was injured and was placed on the DL in late July. Though he attended several tryouts over ensuing years, he could not catch on and never made it back up to the majors again. He had certainly found success; in his 12 seasons as a major-leaguer, he had connected for 105 home runs, and carried a respectable .254 career batting average. He said he loved the game and wished he could have been at it longer. He thought that as an established veteran, having had larger salaries in the past, he was competing with the ballplayers just starting out in their careers who were more economical for organizations and that baseball executives probably perceived he would want more money. But he just wanted to play baseball. It was not about the money.31

“That was tough, because, and this is every ballplayer, I’m sure, that thinks … they can still play and I still thought I could,” Devereaux said a decade after he had played his last big-league game. “It took probably about five, six years before I really settled into the fact that I’m not going to be playing anymore.”32

After retiring, Devereaux stepped away from baseball, and concentrated on spending time with his family and growing business interests. He initially got involved in the private sector combining his entrepreneurial marketing and people skills, including working for a business providing outsourcing services, where he managed 35 people, and also for a time serving as a representative for a start-up company working to supply natural foods, including dietary and vitamin supplements, fortified dairy products, and citrus fruits, to major-league clubs, but in the era when baseball was extremely skittish about bringing any products from outside vendors into the clubhouses, it was admittedly a tough sell. He kept his hand in baseball by also starting up in 2003 and running for seven years a baseball academy near Atlanta at which he provided personal hitting instruction for youngsters 6 through 18.33

After being out of Organized Baseball for several years, Devereaux decidedly missed it. He had always been interested in sharing his knowledge on hitting and so he returned to the game in 2010, getting involved in player development in the minor leagues. He was offered a job as a field coach for the Orioles’ affiliate in the Class-A South Atlantic League, the Delmarva Shorebirds. The following season he shifted to become a field coach with another Orioles Class-A affiliate, the Frederick Keys in the Carolina League.

In 2012 Devo was hired by the Colorado Rockies to be the hitting coach for the Asheville Tourists, in the SAL, a job he held for five years. In 2017 Devereaux was assigned to coach the Boise Hawks, the Rockies’ affiliate in the short-season Class-A Northwest League. After six years with the Rockies, Devereaux moved into the Cincinnati Reds system. He became the hitting coach of the Pensacola Blue Wahoos in the Double-A Southern League in 2018. They changed their major-league affiliation in 2019, and Devo took on a new assignment as the hitting coach for the Reds’ team in the Class-A Midwest League, the Dayton Dragons.34

Baseball has changed since Devereaux first broke in, of course. While understanding the importance of using today’s analytical data, he said he believed there is an overemphasis on teaching younger players coming up to produce launch angles, leading to uppercut swings, which can be detrimental for long-term player development. By trying to hit the ball over the fence, in part to try to avoid the extreme defensive shifts in today’s game, players are instead increasingly rolling over on the ball or striking out, he commented. To neutralize the shift, batters should learn to hit the ball where the ball is pitched and practice hitting it the other way, spraying hard line drives, and using all fields.35

Reflecting back to his earliest days, he said, “I was blessed to have been coached by former big leaguers in the Dodgers and Orioles system, some of the veterans who themselves were Hall of Famers.”36 This included receiving tips from, among others, Roy Campanella, Tommy Lasorda, Sandy Koufax, Frank Robinson, Brooks Robinson, Jim Palmer, and Eddie Murray, all today enshrined in Cooperstown. Other former players he gave credit to include Boog Powell, Johnny Oates, Tommy McCraw, and Curt Motton.37

As a player who worked hard to achieve his own dreams, Devereaux always wanted to repay the opportunity he had to give back to the community. While with the Orioles he was involved with both the Back to School and Athletes Against Drugs programs in the Washington metro area, visiting schools and advising at-risk youth on approaches to help sidestep life’s pitfalls. He also founded Mike Devereaux’s Orioles, a program supplying baseball equipment and upgrading local ballfields for young people.

Nor did he forget his hometown, establishing the Thumbs Up Youth Foundation in Casper, Wyoming, an academic program in area schools promoting the growth and development of students by stressing the importance of good study habits and setting personal goals. He has participated in the Legends for Youth Baseball Clinics sponsored by the Major League Baseball Players Alumni Association. A resident of Ruskin, Florida, outside Tampa, in 2020, Devereaux is married and is the parent to five children, the youngest of whom are a 7-year-old daughter and an 8-year-old son, whom, he said, he enjoyed personally coaching, much as his father did with him and his brothers while growing up in Casper. It’s a family tradition being passed down to another generation.38

Last revised: February 15, 2021

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and the 1986-1989 and 1998 Media Guides of the Los Angeles Dodgers and the 1990-1993 Media Guides of the Baltimore Orioles.

Berney, Louis. Tales from the Baltimore Orioles Dugout (New York: Sports Publishing, 1916).

Dempsey, Rick, and Dave Ginsberg. If These Walls Could Talk: Baltimore Orioles (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2017), provided context for the Baltimore Orioles during this era.

The author wishes to thank Mike Devereaux for a telephone interview, conducted on November 25, 2019, and providing follow-up information via email.

Notes

1 “Devereaux Delivered as MVP,” Honolulu Advertiser, October 15, 1995.

2 Mike Devereaux, email communication, December 4, 2019. He was such a fan of Jackson, in fact, that when Reggie became a Yankee in 1977, Devereaux switched his allegiance to New York. He had also idolized Dave Winfield growing up and was thrilled to later play against him. He harkened back to an “incredible” conversation he had with Winfield during an extended rain delay in Cleveland in 1995, the last season of Winfield’s Hall of Fame career.

3 Don Marcus, “Devereaux Beats Odds to Become a Star,” Baltimore Sun, September 20, 1992; SABR, US Baseball Questionnaires, 1945-2005, Box Number: 555698, Michael Devereaux, June 24, 1985; “Devereaux Spends Time Chasing Big League ‘Dream,’” Casper Star-Tribune, June 11, 1987.

4 Sally Ann Shurmur, “Casper’s Fred Devereaux Doing Well on the Mound,” Casper Star-Tribune, July 9, 1980; Shurmur, “Devereaux Faces New Chapter,” Casper Star-Tribune, May 27, 1981. Devereaux was inducted into the National Federation of State High School Associations National High School Hall of Fame in 2014. Email communication from Mike Devereaux, November 28, 2019. The American Legion chapter in Casper sponsors the annual Mike Devereaux Invitational, a round-robin baseball tournament to be held for the 13th time in July 2020. https://legion.org/baseball/tournaments/invitational/159124/mike-devereaux-invitational, accessed November 17, 2019.

5 Technically it was called the National Junior College Athletic Association Tournament.

6 Jay Thorne, “Thunderbirds’ Coach Pleased with Tourney,” Arizona Republic (Phoenix), June 9, 1982; Initially Mike’s two older brothers had attended ASU, but Ron had transferred to Mesa Community College for his sophomore year before going on to graduate from Texas A&M and Fred Jr. had transferred from ASU to the University of Houston. Mike’s sister, Phreda, went on to graduate from Harvard University, earning straight-A grades. Mike Devereaux, email communications, November 28 and December 4, 2019.

7 “Three-Team Dogfight Expected for Six-Pac Title,” Arizona Republic, February 26, 1984; Bill Landen, “Sidelights to Be a Part of Tournament,” Casper Star-Tribune, March 8, 1984.

8 Devereaux had wrecked his knee during basketball practice in his senior year and was told he would not be able to play baseball in college without undergoing major reconstructive surgery. He underwent arthroscopic surgery on his knee and was out for eight months. After some additional treatment, he did not miss any regular-season games with Mesa Community College, though he played wearing a brace. Mike had the recommended reconstructive knee procedure at the end of his freshman year in college; the medical team told him he would be out for an entire year. But when the baseball season came around, through sheer determination and by adhering to a rigorous physical therapy regime, Devereaux was not only back in uniform, but he overcame the surgery to steal 16 bases in 20 attempts in 1984. He had beaten the long odds, which could have conceivably derailed his major-league career even before it began. He gave ample praise to his surgeon. The knee never bothered Devereaux again during his big-league career. William J. Weiss, 1986 Los Angeles Dodgers Organizational Record Book (St. Petersburg, Florida: Baseball Library, 1987), n.p.; Mike Devereaux, email communication, November 28, 2019.

9 Arizona State University, Sun Devil Baseball Media Guide, 2018: 33; 41; 67.

10 Weiss, 1986 Los Angeles Dodgers Organizational Record Book.

11 Weiss, 1987 Los Angeles Dodgers Organizational Record Book (St. Petersburg: Baseball Library, 1986), n.p.

12 “Michael Devereaux – Elected to the National High School Hall of Fame – Class of 2014.” YouTube.com video uploaded on July 14, 2014, accessed at https://youtu.be/YGbIszZH5Js.

13 Mike Devereaux, telephone interview, November 25, 2019.

14 Sportswriter Thomas Boswell once related the story of how Orioles general manager Roland Hemond, who had had his eye on Devereaux as he was progressing through the minors, essentially stole him away from the Dodgers. Hemond had nonchalantly inquired about their young prospect in his early trade discussions with the Dodgers, deliberately mispronouncing his name. Thomas Boswell, “Fans Shouldn’t Judge This Week’s Trade Just Yet,” Austin American-Statesman, August 3, 1997.

15 Bob Wolf, “Devereaux Is Traded to Orioles in Exchange for Pitcher Mike Morgan,” Los Angeles Times, March 12, 1989.

16 Wolf.

17 Mike Devereaux, telephone interview, November 25, 2019.

18 Mike Devereaux, telephone interview, November 25, 2019.

19 Mike Klingaman, “Catching Up with Mike Devereaux: Why Not? A Fair Question,” Baltimore Sun, August 26, 2009.

20 “Mike Devereaux Reminisces on 1989 ‘Why Not’ Orioles,” YouTube.com video uploaded on August 9, 2019, accessed at https://youtu.be/channel/UCs6xk3YBIP3LMtoc9hDZQiQ.

21 “Mike Devereaux Reminisces on 1989 ‘Why Not’ Orioles”; Mike Devereaux, telephone interview, November 25, 2019.

22 Thomas Boswell, “Devo Steals, Chase Is On,” Washington Post, June 6, 1992.

23 Klingaman.

24 Tom Keegan, “Devereaux’s Cheek Swollen but Unbroken,” Baltimore Sun, May 9, 1994; Jon Miller, Confessions of a Baseball Purist (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1998), 127-128; Ken Rosenthal, “Signing on with White Sox Right Turn for Devereaux,” Baltimore Sun, April 11, 1995.

25A Braves second-round draft pick, King never made it beyond Double-A, and he was out of baseball altogether before reaching the age of 24. See King’s statistics at baseball-referencecom; accessed October 23, 2019.

26 Andrew Bagnato, “Devereaux’s Blast Socks It to Reds,” Chicago Tribune, October 15, 1995; Steve Dilbeck, “Devereaux Journeys into Hero’s Role,” San Bernardino County (California) Sun, October 11, 1995. One of the thrills of going to the Braves for Devereaux was meeting up on a few occasions with one of his boyhood heroes, Hank Aaron. Bob Berhaus, “Inspiring Blast from the Past,” Asheville (North Carolina) Citizen-Times, April 9, 2014.

27 Mike Devereaux, telephone interview, November 25, 2019.

28 Ailene Voison, “Devereaux Latest Hero in Braves Playoff Lore,” Atlanta Constitution, October 15, 1995; “Devereaux Delivered as MVP.”

29 Mike Devereaux, telephone interview, November 25, 2019.

30Jason LaCanfora, “Devereaux Not Thrilled by Brave New World,” Baltimore Sun, June 22, 1996.

31 Mike Devereaux, telephone interview, November 25, 2019.

32 Patrick Schmiedt, “Devereaux Makes Peace with Life After Majors,” Casper Star-Tribune, June 29, 2008.

33 Jack Daly, “Devereaux Still Chasing … This Time It’s His Toddler, Not Fly Balls,” Casper Star-Tribune, May 11, 2003; Mike Devereaux, telephone interview, November 25, 2019.

34 Keith Jarrett, “Three for Three: Tourists Have Led the League in Batting Each Year Under Devereaux,” Asheville Citizen-Times, July 31, 2014; Pensacola (Florida) News Journal, January 18, 2018; Marc Pendleton, “Dragons to Bring Back Manager for Third Straight Season,” Dayton (Ohio) Journal-News, January 10, 2019.

35 “Mike Devereaux Reminisces on 1989 ‘Why Not’ Orioles”; “The Ross Grimsley Show,” https://pressboxonline.com/2019/07/25/former-oriole-current-minor-league-coach-mike-devereaux-on-changes-in-player-development, accessed October 7, 2019.

36 Mike Devereaux, telephone interview, November 25, 2019.

37 Mike Devereaux, email communication, December 4, 2019; Ted Leavengood, “Touring the Bases with Mike Devereaux,” https://seamheads.com/2011/06/09/touring-the-bases-with-mike-devereaux, accessed November 17, 2019.

38 Russ Blake, “Devereaux: Starring at Camden Yards”; “Thumbs Up Youth Foundation,” Casper Star-Tribune, January 28, 1996; “Major League Baseball Players Alumni Association Brings Legends for Youth Baseball Clinic Series to Sarasota, FL,” October 6, 2019; news.cision.com accessed November 7, 2019; Mike Devereaux, telephone interview, November 25, 2019.

Full Name

Michael Devereaux

Born

April 10, 1963 at Casper, WY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.