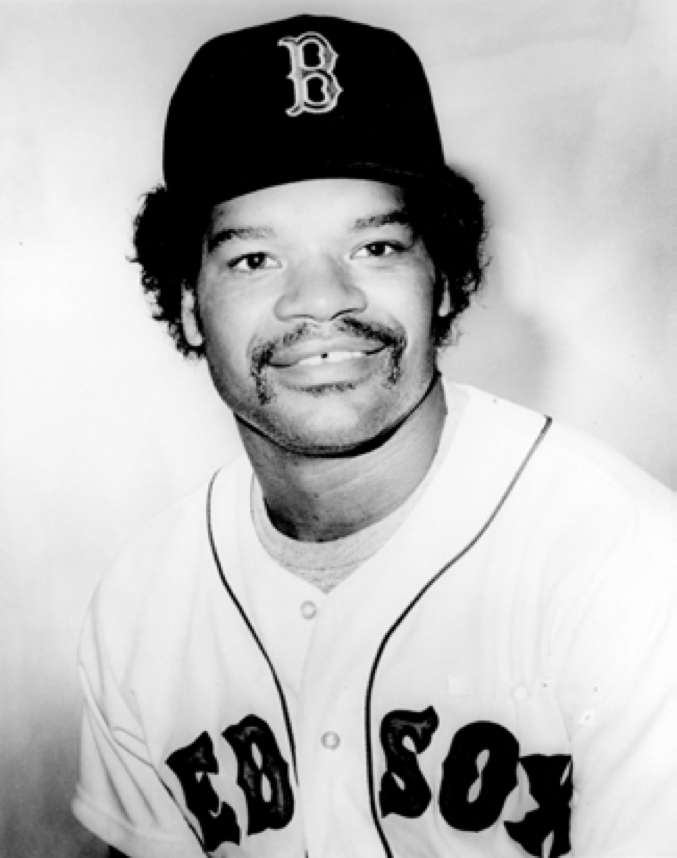

Dave Henderson

The gap-toothed smile of Dave Henderson is emblematic of the exuberance that he brought to the game and which he displayed unabashedly after slugging a playoff home run for the ages. A native of Merced, California, in the state’s Central Valley, Henderson was born on July 21, 1958, eventually filling out as a strapping 6-foot-2-inch, 210-pound athlete gifted in two major sports. He graduated from Dos Palos High School, where he was named an All-American in football as a running back and in baseball. “I was a lot better in football. I can’t explain why I chose baseball,” Henderson recalled in 1981.1 A decade later, however, he confessed that the $100,000 bonus from the Mariners far outweighed the value of a $40,000 scholarship from any of the colleges that pursued him.2

A lanky right-handed batter who also threw right, he was the nephew of pitcher Joe Henderson, who had a cup of coffee with the Chicago White Sox (1974) and the Cincinnati Reds (1976 and 1977). Dave Henderson drew the notice of Seattle Mariners scouts Bob Harrison and Tom Laspina, who signed him after he was selected in the first round of the 1977 amateur draft, the 26th pick overall.

Shortly after the draft, Henderson broke into minor-league ball with the Bellingham Mariners of the short-season Northwest League and tied for the league lead with 16 home runs while driving in 63 runs in 65 games and hitting a robust .315. One sore spot was his error total of 11, but his overall effort propelled the team to the division crown and the league championship over Portland. Henderson was one of four “Baby M’s” to achieve all-star status, and he garnered honors on the Topps Class A/Rookie All-Star team.

The next year at Stockton of the Class-A California League, Henderson slumped to .232 with only 7 homers and reached the century mark in strikeouts. His alarming total of 14 errors in the field punctuated a down year during which he was hobbled by a problem with his Achilles tendon.

Remaining in the California League in 1979 – this time with San Jose – Henderson rebounded with an all-star campaign (.300, 27 HR, 99 RBIs, second-best outfielder, with more than 100 games played) which helped his club reach the league playoffs and capture the league championship. While achieving the distinction of leading the circuit by reaching base five times via catcher’s interference, he more importantly was recognized by the league’s coaches as the best defensive outfielder in the league and was also ranked as having the best arm among its flychasers.

Henderson’s breakout year earned him a jump past Double-A ball and on to the Pacific Coast League Spokane Indians in 1980. Missing almost four weeks due to a stint on the disabled list for arthroscopic surgery on some bone spurs, Henderson saw his production fall off (.279, 7 HRs, 50 RBIs) in 109 games played, and he was again ticketed for more seasoning in the PCL.

But at the major-league level, the Seattle Mariners were retooling much of their roster in an attempt to shake themselves out of the expansion funk in which they seemed trapped since entering the American League in 1977. There was a new owner, George Argyros, and manager Maury Wills, who had replaced Darrell Johnson midway through the 1980 season, was intent on allowing a youth movement come to the fore. Such was the milieu of the Mariners’ 1981 spring-training camp, and while priority was being given to young Seattle pitchers, the opportunity for Henderson to make the major-league roster was hardly a given. “Maury didn’t know me that well,” he said at the time, “[but] I felt if I showed him what I could do, it would make it tough on him to send me down.”3

Beginning March 18, Henderson embarked on a 12-game hitting streak and ostensibly demonstrated his readiness to don a major-league uniform.4 Henderson’s performance impressed enough to ensure his place as the starting center fielder on Opening Night at the Kingdome versus the California Angels. However, the reality of major-league pitching soon set in, and the 22-year-old Henderson was returned to Spokane, where he once more gained his footing and earned all-star honors for the third time. In a Seattle uniform for all of 1981, Henderson logged only 126 at-bats and posted a .167 average. However, six of his 21 hits were home runs, a portent of the power stroke he would develop over the ensuing years of his career in the majors.

Entering 1982, Henderson proved that he was ready to abandon his journey in the minor leagues, and with the exception of two brief stays on the disabled list in May 1982 and August 1984, he remained on the Mariners’ roster through the summer of 1986. Splitting time between center field and right field – center was his primary station – Henderson displayed the solid defensive skills he had shown in the minor leagues, posting 11 assists in 1982 and 17 in 1983. His speed on the bases was never evident in the stolen-base department, but he legged out a pair of inside-the-park home runs in 1983.

Hitting-wise, Henderson matured fairly quickly in his second season (1982), batting a respectable .253 with 14 homers and 48 RBIs in 324 at-bats, and his numbers (.269, 17 HRs, 55 RBIs, 9 steals) continued to offer encouragement in his third year with Seattle. The plight of the Mariners through the mid-1980s is noteworthy as they were in the throes of a streak of consecutive losing seasons that would eventually reach 14 years (1977 to 1990), but in 1984 a glimmer of hope emerged when Seattle caught a mild case of pennant fever by moving within six games of first place in the weak American League West in early August. Bolstered by newcomers Alvin Davis and Mark Langston, the Mariners seemed poised to shake themselves from the depths of their division. But the race brought unwelcome pressure to bear on the club – not least of which was a brawl between coach Frank Funk and catcher Bob Kearney, and the season quickly unraveled. As Seattle folded, Henderson was helpless to his team because a hamstring injury relegated him to the disabled list for most of August. Turmoil created casualties among the field leaders when Funk was axed as the pitching coach and manager Del Crandall also lost his job before the season concluded. Through the wreckage, Henderson, when healthy, maintained a hold on center field. His final numbers (.280, 14 HRs, 43 RBIs) were solid but unspectacular.

Chuck Cottier had been handed the managerial reins to close out the 1984 campaign, and he was again at the helm for the 1985 season. Still patrolling center field, Henderson drove in 68 runs and matched his home-run output of the previous year, but he slipped in batting average (to .241) and swung too freely in amassing 104 strikeouts. The Mariners equaled their win total of 74 from the previous year, but entering 1986 they were at a crossroads. Many of their regular players were barely in their mid-20s – Alvin Davis, Harold Reynolds, and Spike Owen were 25 years old, Jim Presley was 24, Danny Tartabull just 23 – and the four main starters (Mark Langston, Mike Moore, Mike Morgan, and Bill Swift) were between 24 and 26. When the Mariners stumbled to a 9-19 start under Cottier – and then lost their 20th game for interim skipper Marty Martínez – Seattle then came under the critical gaze of future Hall of Fame skipper Dick Williams. A stern manager with a reputation for winning, Williams was one year removed from taking the San Diego Padres to the National League pennant, and he was hired to reshape the Mariners’ roster with the intention of at last breaking the .500 barrier.

While hardly an elder statesman at the age of 27, Dave Henderson nevertheless found his way into the crosshairs of Williams’s scope. Upon arrival in Seattle, the new manager first targeted five aging veterans who were pared from the team as the season wore on. Al Cowens, Milt Wilcox, Gorman Thomas, Barry Bonnell, and Steve Yeager were pruned from the roster and supplanted with younger blood from the minor leagues. Among them was John Moses – a “hustler,” according to Williams – who, like Dave Henderson, played center field.

Prior to the arrival of Williams, Henderson had fought his way out of a slump that dogged him the first month of 1986, but as the summer progressed, his average climbed and peaked with a hardy .348 in July. But underlying this surge was a festering issue between Henderson and his manager that led the center fielder to label Williams “the worst manager in baseball.”5 Taking umbrage at a player “to whom everything was funny” and who “laughed even when [the team] lost,” Williams had Henderson dispatched to the Boston Red Sox in a trade that also sent shortstop Spike Owen east in exchange for shortstop Rey Quinones, pitchers Mike Brown and Mike Trujillo, and outfielder John Christensen sent later as a player to be named.6

Running counter to Williams’s judgment of Henderson, however, was the fact that Henderson’s façade was indicative of his genuine pleasure in playing baseball, but this was also a trait not to be confused with the intensity of concentration on the field when it mattered. “I’ve learned life from football,” he commented in the spring of 1991, a statement shot through with the discipline inherited from participating in a sport that demands an acute level of focus on each play as opposed to the more relaxed pace of baseball. Henderson defended his performance vis-à-vis his comportment on the diamond: “Me having fun takes nothing away from me doing my job. In fact, I’m probably the most concentrated guy out there.”7

The fun-loving side of Henderson’s demeanor endeared him to legions of fans, especially those in the bleachers, who engaged him in conversation between innings, even between pitches. “You have to remember, we do have a lot of free time out there, so you can see me screwing around with fans…If the fans ask you a question, you can answer it. It’s really part of just being a human being.”8

Upon arrival in Boston, where Tony Armas was the Red Sox’ regular center fielder, Henderson’s role diminished to that of a fill-in; he had only 54 plate appearances over the last 36 regular-season games and failed to hit his weight as he batted only .196. For 1986, Henderson logged numbers similar to those of two years prior (.265, 15 HRs, 47 RBIs), but having been banished to a new team as well as an unaccustomed seat on the bench, he was a mere spectator as his club captured the AL East title. It appeared that Henderson’s role entering the 1986 American League Championship Series would be that of pinch-hitter, a far cry from the heights he reached in fulfilling his promise as a first-round draft pick who seemed to have made good on his potential.

Not surprisingly, the bench is exactly where Henderson could be found for most of the first four games of the ALCS against the California Angels. In Game Two he came in as a defensive replacement in the top of the eighth inning, and in Game Four he did likewise in the bottom of the seventh, flying out in the ninth in his only trip to the plate. Entering Game Five in Anaheim, the Red Sox were down three games to one in the best-of-seven series, and Henderson again began the day watching from the Boston dugout. But when Armas suffered an ankle sprain, Henderson took his place in the bottom of the fifth, thereby embarking on a Jekyll-and-Hyde outing that became legendary in postseason play.

With two out in the Angels’ half of the sixth inning, California’s Doug DeCinces hit a double to right field, bringing Bobby Grich to the plate. On a 1-and-2 pitch from Bruce Hurst, Grich drove a ball to deep center field as Henderson ran back attempting the catch. Timing his leap perfectly just as he approached the fence, Henderson snared the drive as it was coming down, a play worthy of any highlight reel. But when Henderson’s left forearm smacked against the top of the fence, the ball popped loose and, in essence, was deflected over the barrier for a stunning two-run homer that gave the Angels a 3-2 lead.

“I had the ball in the palm of my glove, but then I lost it when my wrist hit the wall,” the smitten center fielder said after the game.9 Henderson then closed out the top of the seventh for Boston by striking out, thereby compounding his own misery as well as that of the Red Sox when the Angels padded their lead with two more runs in the home half of that inning.

With ace Mike Witt on the mound and still in control in the ninth, the Angels were poised to secure their first trip to the World Series. But fate intervened as Bill Buckner opened with a single and Don Baylor followed one out later with a two-run home run to cut the California lead to 5-4. Dwight Evans popped out to third for the second out, and Angels manager Gene Mauch, trying to shake the ghosts of collapse that had nagged at him since his 1964 Phillies blew the National League pennant, summoned southpaw Gary Lucas to face the left-handed-hitting catcher Rich Gedman. Witt had not been able to solve Gedman in Game Five, so Mauch played the percentages by opting for his best lefty reliever. The move, however, backfired when Lucas plunked Gedman with the only pitch he would throw, and Mauch again followed the book by bringing in right-handed closer Donnie Moore to deal with the next scheduled batter – Dave Henderson. Perhaps little was expected of Henderson: In 1986 he had one hit in 13 at-bats in late-inning pressure situations (two out with runners on), including nine strikeouts, and furthermore he had no home runs with two outs and runners on in 71 such plate appearances.10

Despite being credited with a save in Game Three two days earlier, Moore had pitched poorly, and Henderson struck at an opportune moment. Working the count on Henderson to 2-and-2, Moore labored to bring the Angels to just a single pitch away from the AL pennant. But the Red Sox center fielder spoiled the celebration by lofting a home run over the fence in left field to give Boston a 6-5 lead. Yet in another statistical sense, Henderson’s derring-do should not have come as too much of a surprise. Henderson had faced Moore in similar circumstances in August 1985 and hit a game-tying homer at the Kingdome. In fact, throughout his career to that point, Henderson had averaged a home run every 27.18 at-bats, a number on a par with some other sluggers of that era including Tim Wallach, Jody Davis, Dave Parker, and Kevin McReynolds. This latest clout breathed life into the Red Sox and would prove to be Henderson’s only hit in the ALCS.

When the Angels dramatically knotted the score in the bottom of the ninth and remained tied entering the 11th, Henderson completed his vindication by plating the winning run with a sacrifice fly off Moore to cap the Red Sox win. “I was glad to get the chance to make up for not holding onto [Grich’s fly ball],” said Henderson.11 And with the series shifting back to Boston, the pendulum of good fortune continued to swing in favor of the Red Sox, as they took Games Six and Seven. With Henderson now a fixture in the lineup, he contributed with an RBI and a run scored in Game Six and scored again in the Game Seven clincher to send Boston into the World Series against the New York Mets.

Continuing to play a hot hand, Henderson did well in the World Series by batting .400 in the seven-game set. Among his 10 hits were two more home runs, one off Dwight Gooden in Boston’s Game Two win and another stirring shot in the 10th inning of Game Six that put the Red Sox ahead 4-3. But just as Henderson had delivered Boston from the precipice of defeat in the ALCS, so too would the Mets rebound when faced with elimination by plating three runs to win Game Six – this aided by the infamous Bill Buckner error – and then claim Game Seven and the Series crown. In the finale, Henderson walked and scored in the second inning and was hit by a pitch in the fourth, but New York overcame a 3-0 deficit in the sixth by scoring eight times over their final three innings to take the Series.

For Henderson, his celebrity in Boston was ephemeral. In 1987, Henderson opened as the center fielder but was hampered by a slow start in which he ended April hitting a tepid .239, with 3 home runs and 18 strikeouts. As Boston quickly fell off the pace in the AL East, manager John McNamara elected to go with a youth movement of his own by installing rookie Ellis Burks in center field and spelling Jim Rice occasionally with Mike Greenwell in left field. Henderson was back in the same bench-warming role as he was when he first joined the Red Sox, and Boston’s outfield became even more crowded upon the arrival of Todd Benzinger, who played right field and first base. Veteran Don Baylor continued to serve as the designated hitter, so the odd man out in the lineup ended up being Henderson. By the end of August, Red Sox general manager Lou Gorman found a new home for Baylor by trading him to Minnesota and for Henderson by sending him to the San Francisco Giants for outfielder Randy Kutcher. Gorman tried to be tactful in explaining the circumstances of Henderson’s departure – “He did everything we asked of him, but Burks just came along and took his job” – but the outfielder was bitter in conceding to the reality of his fate. “I was getting disgusted because I wasn’t getting a chance to play, but I understood why,” said Henderson, who nonetheless vowed, “I’m not done yet.”12 In his month with the Giants, Henderson played in 15 games and hit .238 (5-for-21).

Signed as a free agent by the Oakland Athletics in December 1987, Henderson took a pay cut in order to hang on with a big-league club, and his prospects for playing time looked inauspicious. Joining manager Tony La Russa’s already potent roster was slugger Dave Parker, and holdovers José Canseco (right field) as well as leadoff hitter Luis Polonia (left field) meant that Henderson would have to duel Stan Javier for the starting role in center. In its 1988 spring preview, The Sporting News never mentioned Henderson, whose entry with the Athletics’ 40-man roster impressed as little more than a footnote for a career on the wane, and a feature article on Oakland’s prodigious offense in a May issue of that publication mentioned him only in passing.

Facing the same last-strike challenge he had encountered in Game Five of the 1986 ALCS, however, Henderson rose to the occasion and won the center-field job in convincing fashion. For the 146 games he played in 1988, Henderson batted .304, belted 24 home runs, drove in 94 runs, and scored 100 times. After he began the season batting sixth, his consistent hitting prompted La Russa to move him in early June to the number-two spot ahead of Canseco, which was “just the medicine for Henderson,” according to The Sporting News.13 For each month of the season, Henderson batted between .291 and .321 and hit three to six home runs. With much attention focused on Oakland’s “Bash Brothers” tandem of Canseco and first baseman Mark McGwire, Henderson was able to maintain a lower profile in a power-laden lineup, circumstances that contributed to his flourishing. Given the chance to play, Henderson was confident of being able to post good offensive numbers. “I said at my press conference that when (Glenn) Hubbard and me are down in the lineup, we’re going to get a few cookies to hit. It’s turned out that way,” he stated in early August.14

The Athletics’ record in games in which Henderson hit a home run was 23-1, and his teammates seemed in sync for much of the year as well, Oakland cruising to the best record in the American League (104-58), 13 games ahead of division runner-up Minnesota. The postseason matchup against AL East champion Boston again showcased Oakland’s strength in a four-game sweep of the Red Sox for the American League pennant. Henderson showed no sign of letting up as he hit safely in each contest (6-for-16, .375) and drove in four runs. Against the underdog Los Angeles Dodgers in the World Series, Henderson fared well, batting .300 on 6-for-20, but four of those hits came in a losing effort in Game Four, and he drove in only one run in the five-game Series loss.

The stinging rebuke in the fall classic did little to dissuade Henderson from rejoining the Athletics. Four days after the end of the Series, he filed for free agency shortly before departing for Japan with an ensemble of major leaguers for games against a squad from Nippon Professional Baseball. Cognizant of his negotiating leverage now that his best year in the majors was just concluded, Henderson declined to become involved with the business side of the game – “I play the baseball and [my agent] takes care of the contracts and all that stuff,” he said – but he officially remained in an Oakland uniform when he re-signed a two-year deal worth $850,000 each year.15 This was a handsome increase from the $450,000 he received his first year with the Athletics and also a nod to his finishing in 13th place in voting for the American League Most Valuable Player award.

Henderson was determined to prove that he was worth the value of his new contract, and did so convincingly in 1989 spring training by leading American League batters in average (.448), slugging (.836), and on-base percentage (.500). Some of this good fortune carried over to the beginning of the regular season when he hit .308 with four homers and 13 RBIs in April despite the absence of José Canseco, who was out with a wrist injury. As Oakland dealt with other injuries to key members of the lineup at various times throughout the year – Mark McGwire and relief ace Dennis Eckersley among them – Henderson endured extended slumps in June and August yet persevered to finish with a .250 average, 15 home runs, and 80 RBIs. Oakland captured the American League West with 99 victories, thanks in part to the addition of another Henderson – ex-Yankee Rickey, who was traded back to Oakland on June 21 – to the top of the batting order.

In defeating the Toronto Blue Jays four games to one in the ALCS to defend their league pennant, Oakland benefited from Dave Henderson’s glove more than his bat. Although he hit a solo homer in the first Athletic win and batted .263 for the series, Henderson recorded 22 putouts, more than Rickey Henderson (13), Canseco (6), and Stan Javier (1) combined. When Oakland squared off against the San Francisco Giants in the earthquake-marred World Series, Henderson batted .308 on 4-for-13, with two homers and four RBIs in the third game of the Athletics’ four-game sweep.

The Oakland dynasty under Tony La Russa’s guidance peaked with his only World Series crown in an Athletic uniform, but his team still showed in 1990 that it was worthy of yet another league pennant. With two Hendersons now available for the entire season in the outfield and a track record of 306 wins over the past three seasons, the Athletics were primed to keep lording over the American League. Holding off the charge of the pesky Chicago White Sox during the early summer, Oakland outdistanced its foes in the AL West and won 103 games. For his part, Henderson played not as active a role as he would have liked. Most of his contributions came prior to his landing on the disabled list on August 21, and until that time Henderson had swung the bat with authority. But during a game at Comiskey Park, he tore a ligament in his right knee, an injury that required an arthroscopic procedure and shelved the Athletics’ “inspirational leader.” Vowing to be back in time for the end of the campaign despite a prognosis of a minimum of four weeks on the sidelines, Henderson declared, “I already sold my soul for those postseason home runs. The devil ain’t getting off that cheap.”16

Upon his return one month later, Henderson was limited to pinch-hitting and DH appearances but got back in the outfield for five games before the end of the regular season. His line for the whole campaign was still impressive: .271 average, 20 homers, 63 runs batted in. In the ALCS against Boston, Willie McGee, who had been acquired from St. Louis a week after Henderson underwent surgery, assumed duties in center field for the first two games. Henderson resumed his place in center for the last two contests, hitting a single and sacrifice fly – as well as testing his knee by stealing a base – in Oakland’s Game Three win, and going hitless in the fourth game, in which the Athletics defeated the Red Sox for their third straight American League pennant. Facing Cincinnati in the World Series, this time Oakland would become the victims of a sweep as the underdog Reds closed out the Athletics in four games. Henderson fanned as a pinch-hitter in the first contest and started the last three games in center field, going 3-for-13 and batting .231 overall. In the ninth inning of the finale, Henderson led off against José Rijo with Oakland down 2-1, but there was no magic moment like four years earlier. Henderson was caught looking on a 1-and-2 count and two outs later, the Athletics were dethroned as World Series champions.

At the close of the 1990 season, Henderson once more became a free agent upon the expiration of his two-year contract. Oakland’s acquisition of Willie McGee proved to be only a stopgap measure as he was also eligible for free agency, but the 1985 National League MVP drew little attention from the Athletics’ front office. Rather, the importance of what Henderson meant to Oakland became clear during the brief bargaining sessions they held with him during the re-signing process. “The A’s hardly bothered to negotiate with Willie McGee … because they wanted to keep Dave Henderson as their center fielder. And with good reason – he’s a fine fielder and clutch hitter, plus he keeps the atmosphere light and lively in both the A’s clubhouse and the bleachers at the Oakland Coliseum.”17 The intangibles Henderson brought to the team in addition to his deeds on the field delivered a huge reward in the form of a three-year contract totaling over $8.3 million. Dick Williams, Henderson’s former manager in Seattle, perhaps had reason to chide his outfielder’s breezy attitude, but he later admitted that he had to “give Henderson credit” despite his “bizarre humor” because he became an integral part of several championship teams.18

If Henderson was complacent after striking it rich, he showed little evidence of it in 1991.

“His batting average was second highest in the majors,” noted the Elias Sports Bureau, “and he owned at least a share of the league lead in RBIs as late as June 12 and in home runs through June 18.”19 Such credentials earned Henderson a spot on the American League All-Star team as the starting right fielder. He was hitless in two trips to the plate during the midsummer classic, but in early August he launched three solo home runs against the Twins. Justify as he might the wealth bestowed on him, Henderson’s accomplishments could not make up for the loss of many of his teammates due to injury. Enjoying his best season since 1988 despite problems with his legs in September, Henderson clouted 25 homers, drove in 85 runs, batted .276, and scored 86 times. In the field, he made only one error – and even put in a cameo appearance as a second baseman – and had a career-high 10 assists. But Oakland players made 16 trips to the disabled list during 1991, among them key personnel such as Carney Lansford, Walt Weiss, Dave Stewart, Rick Honeycutt, and Eric Show. Offseasons plagued Rickey Henderson and Mark McGwire, and in stumbling to an 84-78 record, the faltering Athletics ceded the AL West to the Minnesota Twins.

Looking to rebound in 1992, Oakland was hoping that the injury bug that wreaked so much havoc the previous year would be more forgiving. The Athletics did recover to win 96 games and capture another AL West title, but the disabled list was once again where many players found themselves at one time or another. The dawning of the new season, however, saw Henderson suffering from a strained right calf early during spring training, and he played in only two of the first 20 exhibition contests. A subsequent right hamstring injury forced him to be placed on the DL from March 31 to April 30, yet as the regular schedule commenced, Oakland general manager Sandy Alderson waxed optimistic that current maladies plaguing any of several players would have no adverse impact. “There’s not anybody here we expect is so severely injured they’ll be gone for three months,” said the executive, but the script did not play out as he had hoped.20 Henderson was barely back in the lineup when he again went down on May 6 and did not return to Oakland until September 1.

When Henderson’s name was finally on Tony La Russa’s lineup card on September 1, he was stationed in right field, a position vacated by José Canseco, whose own issues led to his being traded to the Texas Rangers a day earlier. Henderson saw limited action in the season’s final month, but with his hamstring afflicted yet again, he was a nonfactor as the Athletics shuffled various outfielders – including Ruben Sierra, brought in from Texas in the Canseco trade – to finish a year in which they surpassed Minnesota to win the AL West. The bleak 1992 totals for Henderson were only 20 games played, a batting average of .143 (9 hits in 63 at-bats), no home runs, and a mere two runs batted in. La Russa is due all credit for keeping his team victorious through the onslaught of injuries, a remarkable achievement when one considers that the envisioned Oakland outfield of Rickey Henderson, Dave Henderson, and José Canseco – a heady combination of power and speed – never played together in the same contest the entire year.

By 1993 – and now in the final year of his contract – Dave Henderson had to prove that his nagging leg injuries were in the past, yet La Russa was prepared to make alternate arrangements as spring training opened. “I don’t know if he’s absolutely certain in his mind he’s going to hold up. But he’s working,” said the Athletics manager. But he also conceded that Henderson could not be expected to perform as often as he had in his heyday: “I know that he’s not going to be a 162-game player.”21

Henderson met La Russa’s lowered expectations, playing 76 games in the outfield, most of them in his accustomed place in center, but he clearly felt the effects of troubled legs, spending more time (28 games) as a designated hitter in 1993 than he had as a DH in the previous five years combined. Another unwelcome trip to the disabled list with a groin injury took place from June 5 to June 29. To that point, he was batting only .203 with 8 home runs and 15 RBIs, and he had struck out in 40 of 133 at-bats. In the second half of the season, Henderson raised his average marginally to finish at .220, and ended with 20 homers and 53 RBIs. Nothing that most Athletics players did could rescue the club from sinking to last place in the AL West. And just as José Canseco had been swapped the previous year, so too was Dave Henderson’s other outfield partner, Rickey, traded at the end of July to the Toronto Blue Jays. When Dave was granted free agency after the completion of the 1993 World Series, he became a former Athletic in search of a job.

Injuries having rendered Henderson as a liability, only the Kansas City Royals were willing to take a chance on an oft-hurt player in his mid-30s. They signed him in late January 1994 at a drastic pay cut, $750,000, and relegated the former All-Star to the corners of the outfield and to the DH slot, which he shared with rookie Bob Hamelin. At the end of July and shortly before the players followed through on their threat to go on strike, miseries with Henderson’s upper hip took a toll once more and forced him onto the disabled list. When the major leagues effectively ceased operations with the stoppage of play in early August, Henderson’s career also came to an end to all intents and purposes. The Royals extended an offer of assistance to the rehabilitating Henderson and several other injured players, but this proved to be the final curtain for the man with an infectious smile. The tally for Henderson’s last year in baseball shows a .247 average with 5 home runs and 31 RBIs in 56 games.

The trajectory of Dave Henderson’s baseball career began at a relatively high level considering that he was a top draft pick. Making excellent use of his talent to rapidly ascend through the minor leagues, he became a good player on a bad team who moved on to play a vital role with teams that reached the World Series four times in a five-year stretch. His admission to being “kind of weird” emphasized the fact that he was “just a big kid playing baseball.”22 While Henderson’s appearances in five different major-league uniforms may lead some to label him a journeyman, it is doubtful that if given a chance to be spend 14 years in his shoes and travel the same road that he did, few players would turn down the offer.

In his retirement, Henderson served in the Seattle Mariners’ broadcast booth and was a participant at Mariners’ and A’s fantasy camps. He also supported the cause to combat Angelman Syndrome, a genetic condition that affected one of his sons In October 2015, Henderson underwent kidney transplant surgery, but quite sadly he succumbed to a heart attack in Seattle on December 27, 2015 at the age of 57. He was survived by his wife, Nancy, two sons, Chase and Trent, and his first wife, Loni.

Sources

1984 On Deck, Official Program and Souvenir Magazine of the Seattle Mariners.

1986 Boston Red Sox American League Championship Series Program.

1978 Official Baseball Guide, The Sporting News – 1978 through 1992.

Sporting News Baseball Yearbook – 1988-1993.

1988 Sporting News American League Box Score Book, 1988-1992.

The Sporting News.

Sports Illustrated.

1984 Seattle Mariners Media Guide.

1985 Elias Baseball Analyst – 1985, 1987-1992.

Williams, Dick, with Bill Plaschke. No More Mr. Nice Guy: A Life of Hardball (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1990).

Gillette, Gary, and Pete Palmer. The ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia, Fourth Edition (New York: Sterling Publishing Company, 2007).

Mercurynews.com

Baseball-reference.com.

YouTube video of 1986 ALCS Game Five (1:45 into the video shows Henderson tipping Grich’s ball over the fence).

Notes

1 The Sporting News, April 18, 1981, 26.

2 Sports Illustrated, May 6, 1991.

3 The Sporting News, April 18, 1981, 26.

4 Tracy Ringolsby, “Young Henderson Wins an ‘A’ From M’s,” The Sporting News,

April 18, 1981, 26.

5 The Sporting News, August 25, 1986, 16.

6 Dick Williams with Bill Plaschke, No More Mr. Nice Guy: A Life of Hardball (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1990), 298.

7 Sports Illustrated, May 6, 1991.

8 Ibid.

9 1987 Sporting News Guide, 204.

10 1987 Elias Baseball Analyst, 23.

11 The Sporting News, October 20, 1986, 20.

12 The Sporting News, September 14, 1987, 15.

13 1989 Official Baseball Guide, 105.

14 The Sporting News, August 22, 1988, 20.

15 The Sporting News, November 7, 1988, 55.

16 The Sporting News, September 3, 1990, 15.

17 1991 Sporting News Yearbook, 124.

18 Williams/Plaschke, No More Mr. Nice Guy, 298.

19 1992 Elias Baseball Analyst, 110.

20 The Sporting News, April 20, 1992, 31.

21 The Sporting News 1993 Yearbook, 84.

22 Sports Illustrated, May 6, 1991.

Full Name

David Lee Henderson

Born

July 21, 1958 at Merced, CA (USA)

Died

December 27, 2015 at Seattle, WA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.