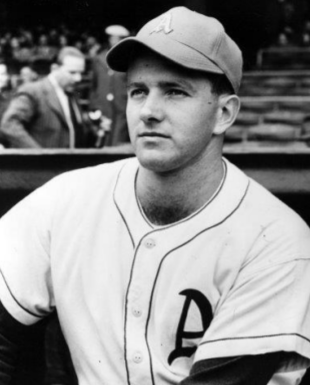

Bill McCahan

In June 1947, three months before his husky right-handed hurler delivered the fifth no-hitter in franchise history, Philadelphia Athletics manager Connie Mack forecast the expected stardom of 26-year-old Bill McCahan. “[Y]ou will see another great pitcher in this boy,” Mack said. “Let me make a prediction. He will be another [Spud] Chandler.”1

In June 1947, three months before his husky right-handed hurler delivered the fifth no-hitter in franchise history, Philadelphia Athletics manager Connie Mack forecast the expected stardom of 26-year-old Bill McCahan. “[Y]ou will see another great pitcher in this boy,” Mack said. “Let me make a prediction. He will be another [Spud] Chandler.”1

Being compared to the American League’s 1943 Most Valuable Player was heady stuff for a blue-eyed, ruddy-cheeked rookie who had entered the 1947 season with just one major-league win under his belt. But McCahan had been in the manager’s sights for years. In 1938 his uncle Izzy Hoffman,2 who three decades earlier had brief stints in the outfield with the Washington Senators and Boston Doves, arranged a tryout for McCahan in Philadelphia’s Shibe Park in front of Mack’s watchful gaze. Shortly thereafter, the future Hall of Fame skipper sent his former ace hurler Jack Coombs, who was managing the Duke University baseball team, to McCahan’s suburban Philadelphia home with an offer to pay the youngster’s four-year tuition to the prestigious college.

The “can’t-miss” label ascribed to the righty over the next nine years was built in part upon the illustrious career McCahan established in college and while pitching for US Army Air Corps teams during World War II. Tabbed by Washington Post sportswriter Shirley Povich as “an amazing member of Connie [Mack]’s fantastic [1948] pitching staff,”3 the youngster appeared poised to take his place among the long roster of great Athletics hurlers. But predictions of greatness quickly disappeared when arm and shoulder problems surfaced after McCahan’s rookie season, ailments that held him to just 107⅓ innings pitched over the remainder of his four-year major-league career.

William Glenn McCahan Jr. was born in Philadelphia on June 7, 1921, the only child of William Glenn McCahan Sr. and Madeline Sarah (Snell) McCahan. Around the turn of the nineteenth century his third great-grandfather, John McCahan, left the town of Ballycastle, on the northeastern tip of what is now Northern Ireland, with his wife and eight children and emigrated to the United States.

The family initially settled in Bradford County in northern Pennsylvania before moving to regions west of Harrisburg, the state capital. Bill’s grandfather, John A. McCahan, was a captain in the 205th Pennsylvania Infantry in the Civil War before moving to Philadelphia after the conflict. He married Lucy Glenn, a Pennsylvania native 12 years his junior. (The Glenn name would be carried by their son and grandson.) Their third child, William — Bill’s father — spent two years in France as a sergeant in the US Army during World War I before being discharged on April 22, 1919. A year later he married Madeline Snell. William launched a long career as a civil servant and, after a move to suburban Bucks County in 1927, became the county highway superintendent.4 When he died in February 1935, Hoffman, Bill’s uncle, stepped in as his surrogate father.

McCahan attended Langhorne Middletown High School (now Neshaminy High) in Langhorne, Pennsylvania, where his nickname, “Wheezer,” may have come from his exhaustive schedule. He participated in the student council (he was the 1938 class vice president), the glee club, and an extensive list of athletic pursuits including soccer, track, volleyball, basketball, baseball, and especially football — all while holding down part-time jobs as a golf caddy or working on a farm.5 A three-time All-County halfback, McCahan received a dozen athletic scholarship offers to play football in college. These offers were spurned in favor of the youngster’s singular desire to follow his uncle’s path into professional baseball. McCahan pursued this passion at a dizzying pace by playing shortstop or third base for his high school, an American Legion squad, and two semipro clubs. In his senior year of high school, McCahan, who disdained pitchers, reluctantly took to the mound after his uncle convinced him he would not reach the professional ranks as a hitter. The youngster went 12-2, missing out on a 13th win though he pitched a 12-inning no-hitter against Bristol High School. (The game ended in a scoreless tie.)

McCahan graduated from high school in 1938 and proceeded to Durham, North Carolina, where he split his extracurricular time playing basketball and baseball for the Duke Blue Devils. (His benefactor, Connie Mack, forbade football for fear of a permanent injury). Among the fastest players on the hardwood court, McCahan helped the basketball team to the Southern Conference championship in 1940 and 1942. In the latter season, he scored 163 of his 219 career points to earn selection as the starting guard on the United Press all-conference first team.6 But McCahan’s primary interest was on the diamond, where he formed an effective mound duo with New York Giants hurler Frank Seward. Using nothing but heat, McCahan had a career record of 24 wins against seven losses. During his four years at Duke he also spent at least one summer pitching for the Bennington (Vermont) Generals in the collegiate Northern League.

After graduating from college in 1942, McCahan was assigned to the Wilmington (Delaware) Blue Rocks in the Interstate League (Class B), the Athletics’ second highest minor-league affiliate. Working closely with Blue Rocks manager Duke Brett, a former Chicago Cubs right-hander, McCahan tried unsuccessfully to master a curveball and changeup (something he never fully achieved throughout his career). He surrendered 35 walks in 77 innings — walks were another career-long challenge — to finish the season with an unremarkable record of 5-3, 3.51 in 22 appearances. Opportunities to expand upon his debut campaign were interrupted on February 24, 1943, when the righty entered the US Army Air Corps during World War II.

McCahan was sent to the 21st College Training Detachment at Colby College in Waterville, Maine, where he received flight instruction. His first assignment was as a B-29 bomber test pilot at Spence Air Base in Moultrie, Georgia. On August 4, 1944, he received a commission as a second lieutenant before being transferred to Maxwell Air Base in Montgomery, Alabama. Throughout his service McCahan earned a record of 61-2 pitching for base teams. During the winter of 1943-44 he also put in a brief stint playing professional basketball with the champion Wilmington Bombers in the American Basketball League. On November 9, 1945, with the war over, he was discharged. McCahan waited out the winter by returning to the Bombers, commuting from his home in Prospect Park, a Philadelphia suburb. He would continue his basketball pursuits over four of the next five seasons.

On the morning of February 17, 1946, McCahan traveled from his home to the North Philadelphia station, where he was among the first players departing on the 11:30 train bound for the Athletics’ West Palm Beach, Florida, spring-training camp. During the camp’s opening weeks, he and fellow pitching prospect Joe Coleman captured great attention as the club looked to improve upon one of the AL’s worst mound staffs. But far less success ensued for both youngsters. On March 31, in the club’s last Grapefruit League exhibition, McCahan was one of three Athletics hurlers clobbered by the International League’s Baltimore Orioles in an 11-10 loss. Shortly thereafter, he and Coleman were assigned to the Triple-A Toronto Maple Leafs.

McCahan was among the team’s leaders in all pitching categories and among the league leaders with a 2.76 ERA — a yield that got him only 11 wins for the league’s worst offense. On June 21, this was made up in part by the club’s strong defense, which turned an International League-record six double plays to aid McCahan in a 10-inning complete-game win over the Syracuse Chiefs. When the season ended, McCahan was among the Athletics’ late season call-ups.

On September 15, 1946, McCahan made his major-league debut in Cleveland Stadium, starting the second game of a doubleheader against the Indians. He scattered seven hits and three walks in a 2-0 shutout win over Bob Feller. Two weeks later, following two successful relief appearances, McCahan made his second start, this time against the New York Yankees in Shibe Park. A second-inning leadoff single by Joe DiMaggio ignited a two-run rally. McCahan yielded just three more hits in a heartbreaking 2-1 complete-game loss on the last day of the season. During the offseason, he moved to New York to play basketball with the Syracuse Nationals in their inaugural season in the National Basketball League. McCahan was not a tall man, listed at 5-feet-11 and 200 pounds. Around this same time Mack, who was considering his options for the 1947 season said, “McCahan made a good impression on me at the close of last season. I think he is ready.”7

The mound youth movement that Mack began in 1946 yielded dividends in 1947 as six pitchers, ranging in age from 20 to 26 years old, collected 60 percent of the Athletics’ starting assignments to help bring an end to the team’s 13 straight losing seasons. The six, who entered the season with a combined .288 winning percentage, included the 26-year-old McCahan who, due to eight rain-canceled assignments, was unable to string two consecutive starts until July. “All I have to do is pick up my glove and it starts to drizzle,” a frustrated McCahan said.8

A strong July 10 performance against the Indians ended in defeat when Cleveland righty Don Black no-hit the Athletics. Six days later, in a four-hit gem against the St. Louis Browns, an error by center-field teammate Sam Chapman was the only thing that stood between McCahan and his second major-league shutout. Another whitewash was lost on July 28 when a streak of wildness ruined eight innings of two-hit shutout pitching. He rebounded from this disappointment with six straight wins in August.

“It was all my fault,” Athletics first baseman Ferris Fain said in a postgame interview on September 3. “I threw the ball while I was still pivoting, and it was five full feet from the bag.”9 The 26-year-old rookie was lamenting his second-inning error on a groundball off the bat of Stan Spence that allowed the Senators center fielder to gain first base. The miscue proved to be the difference between McCahan and the sixth perfect game in major-league history. When the day started, the chances of such a historic event being played out before a tiny crowd of 2,816 seemed most unlikely.

Thirty years had passed since the Senators were handcuffed by a no-hitter when Boston Red Sox righty Ernie Shore famously relieved Babe Ruth after just one batter on June 23, 1917. The odds were even greater considering that until 1947 only six no-hitters had been twirled by a rookie. McCahan’s gem was aided by right fielder Elmer Valo who, in his first game back from an August 9 beaning, accounted for two-thirds of the offense with a seventh inning two-run double after robbing Senators first baseman Mickey Vernon of a sure extra-base hit with a spectacular catch against Shibe Field’s right-field scoreboard. Not until Catfish Hunter’s perfect game in 1968 would the Athletics — by then relocated in Oakland — have a pitcher deliver another no-hitter.

Within two weeks of the 3-0 no-hit win, Mack, who was often strapped for cash, was compelled to publicly deny rumors of a $500,000 offer from the Yankees for McCahan, Fain, and Chapman. The Athletics manager was adamant about not parting with any of the trio, especially the rookie hurler, who finished the season among the team’s leaders in wins (10), ERA (3.32), complete games (10) and innings pitched (165⅓). In October McCahan was selected to The Sporting News All Rookies team alongside future Hall of Famers Yogi Berra and Jackie Robinson while also garnering some consideration for the AL Most Valuable Player Award.

When the season ended, McCahan was prepared to sign an attractive offer from the Boston Celtics to play in the Basketball Association of America (predecessor to the present-day NBA) before Mack interceded. Wanting his promising hurler to rest over the winter, he proffered a $1,000 bonus to persuade McCahan to forgo the offer. The bonus did not cover expenses incurred by the youngster for a new car and a new home. After barnstorming through the United States and Mexico with the Bob Feller All-Stars, McCahan took a job with an oil company loading and unloading drums weighing over 100 pounds. Moreover, McCahan’s successful campaign earned him a regular spot on the rubber-chicken circuit where he gained considerable weight. “I played at many more dinner plates than home plates,” he later confessed. When McCahan reported to Florida in the spring of 1947, tight arm, shoulder, and chest muscles from lifting the heavy oil drums, combined with the added weight, had him struggling “like a man pushing a shot instead of [throwing] a baseball.”10

On April 23, 1948, in his first appearance of the new season, McCahan was fortunate to avoid the decision in a 5-3 loss to the Senators after yielding eight hits and four walks through eight laborious innings. Six days later he was unable to survive the second inning in an 11-5 Red Sox win. Complaining of a sore arm and shoulder stiffness, McCahan took the mound just once over the next 10 weeks. In August he appeared to have found himself with three wins in five starts before imploding with a 12.00 ERA in his last three starts of the season. He finished the year with a disappointing record of 4-7, 5.71 in 86⅔ innings. When the season ended, Mack, eager to ensure that McCahan would not be hoisting oil drums again, readily approved the youngster’s request to play basketball during the offseason.

But a season with the Philadelphia SPHAs (South Philadelphia Hebrew Association) in the American Basketball League, preceded by a two-week barnstorming tour of Eastern Pennsylvania with fellow Keystone State natives Del Ennis, Carl Furillo, and Curt Simmons, did little to alleviate McCahan’s sore arm. When the 1949 season opened, he was brought along very slowly. On May 8, with only one inning of work under his belt, McCahan provided a glimpse of his former potential with seven strong innings against the Chicago White Sox in a 3-2 win. It proved to be his last victory in the major leagues. On June 5, after a 12-day rest, McCahan offered an encouraging performance through two innings against the Indians before his arm gave way in the third. Two weeks later he worked one inning of relief at home against the St. Louis Browns before he was sent to the Buffalo Bisons in the International League. On September 28 the Athletics sent McCahan and $25,000 to the Brooklyn Dodgers for utility infielder Kermit Wahl.

In February 1950 McCahan reported to the Dodgers spring training where, for the first time in three years, he could throw pain-free. “If his arm is sound, he can help us win the 1950 pennant,” Brooklyn GM Branch Rickey said.11 But his restored arm did little in the way of results and McCahan spent the 1950 season bouncing among three of the Dodgers minor-league affiliates. After the season, he traveled south to play winter ball in Venezuela, where he got more than he bargained for following the November 13 assassination of the country’s provisional president. In the ensuing chaos, police stormed Caracas’s Hotel Savoy, where McCahan and other US players were staying. The players “took a severe punching and shoving” before order was finally restored. Within days, most of the US players, presumably including McCahan, left the country.12

There was far less drama in 1951 when McCahan was pitching for the Fort Worth Cats in the Double-A Texas League. He placed among the circuit leaders with a record of 19-9, 2.76 in 228 innings, missing an opportunity for a 20th win when he was called to Philadelphia after his mother contracted a serious illness. (She died two months later.) In 1952 McCahan, seeing little chance of ever returning to the major leagues, accepted a demotion to Class A as player-manager of the Pueblo (Colorado) Dodgers in the Western League. When right-handed pitching prospect Joe Stanka approached his rookie skipper to help him develop a curve, McCahan with only slight exaggeration said, “Joe, I’ve never thrown a curveball in my life. I don’t know how to help you.”13 He led the club to a respectable 81-73 record before retiring from baseball.

McCahan returned to Fort Worth, where he launched a 26-year career with the General Dynamics Corporation, eventually heading an F-16 fighter project. Around 1953, he married Addie Marie Shipp, a Texas native one year his senior.14 The union remained intact until he died 33 years later. On July 3, 1986, McCahan died of cancer one month after his 65th birthday. He was buried at Greenwood Memorial Park in Fort Worth. Three years later, his prep-school exploits on the gridiron were acknowledged with his induction into the Neshaminy High School Hall of Fame.

In the postgame glow of his brilliant September 3, 1947, no-hitter McCahan said, “[s]ome day someone may batter my brains in, and it’s possible I’ll lose a few.”15 The words proved sadly prophetic when the righty lost nine of his last 14 major-league decisions. McCahan never attained the stardom that was once predicted for him. He concluded his four-year career with a record of 16-14, 3.84 in 290⅔ innings.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Ancestry.com and Baseball-Reference.com. The author wishes to thank SABR member Bill Mortell for his valuable assistance. Thanks also to Scott Johnson for pointing out an error in the original version.

Notes

1 “Mack Finding New Marvels at 84 — A’s Play to ‘Standing Room Only,’” The Sporting News, July 9, 1947: 9.

2 Some sources have incorrectly identified McCahan’s uncle as former Philadelphia Athletics centerfielder Danny Hoffman.

3 “Curvers Cutting Fancy Figures in Connie Mack’s Hill Setup,” The Sporting News, April 14, 1948: 9.

4 The September 10, 1947, edition of The Sporting News suggests that as a young man Bill’s father appeared in silent films as a cowboy actor, a claim the author was unable to substantiate.

5 Charles W. Lauble Jr., “Langhorne Trivia,” Historic Langhorne Association. Accessed November 13, 2016 (bit.ly/2etx1Vu ).

6 John Roth and Ned Hinshaw, The Encyclopedia of Duke Basketball (Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2006), 255.

7 “Thin-Man Russ of A’s Weighs Plan to Retire,” The Sporting News, November 27, 1946: 8.

8 “Rain Balks McCahan of Eight Starts,” The Sporting News, July 23, 1947: 11.

9 “Bill Didn’t Think About No-Hitter Until Ninth,” The Sporting News, September 10, 1947: 13.

10 “McCahan Takes Case to Court (Basketball),” The Sporting News, November 10, 1948: 7.

11 “McCahan in Dodger Bid,” The Sporting News, March 29, 1950: 18.

12 Bob Lemke, “American Ballplayers Caught in 1950 Venezuela Police Riot,” January 14, 2014. Accessed November 17, 2016 (bit.ly/2fjXjWJ ).

13 C. Paul Rogers, III, “Joe Stanka.” The Baseball Biography Project, Society of American Baseball Research. Bob Lemke’s Blog, accessed November 15, 2016. (http://bit.ly/2geCobl).

14 One source indicates that when McCahan was in college he was engaged to Amityville, New York, native Charlotte Crump. The author was unable to find evidence that they married.

15 “McCahan, Prof. Coombs’ Diligent Dukester, Makes Varsity Grade on No-Hitter Over Nats,” The Sporting News, September 10, 1947: 13.

Full Name

William Glenn McCahan

Born

June 7, 1921 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

Died

July 3, 1986 at Fort Worth, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.