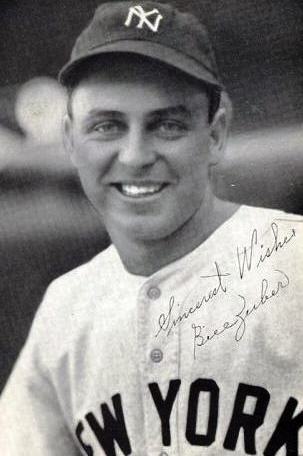

Bill Zuber

William Henry Zuber had a notable major league career for two reasons. First, he was born and raised in a German-speaking religious sect that banned sports and other entertainment. Second, the loss of talented players to service in World War II created the opportunity for him to play a prominent role in several pennant races.

William Henry Zuber had a notable major league career for two reasons. First, he was born and raised in a German-speaking religious sect that banned sports and other entertainment. Second, the loss of talented players to service in World War II created the opportunity for him to play a prominent role in several pennant races.

Bill Zuber was born Wednesday, March 26, 1913 in Middle Amana, Iowa. His parents were members of the Community of True Inspiration, better known as the Amana colonists. The colonists were Christian communalists who believed in self-denial. They emigrated from the German Rhineland to the Buffalo, New York area, and then to seven villages in the heartland of Iowa.

Farming was the primary industry of the self-sufficient colonists. When Bill completed his education at age 14, he went to work as an apprentice cooper. Coopers make and repair wooden barrels, casks, and tubs. The youth of Amana began rebelling in the 1920s. Young people, including Zuber, surreptitiously played baseball and played music. The society embraced the non-religious aspects of culture fairly quickly. As soon as it was allowed, baseball became very popular in the colonies. The first ball field was erected in Middle Amana in the late-1920s and the Amana Athletic Association was formed.

When Zuber began playing baseball, he was a third-baseman. He started pitching in 1930. Zuber is a member of the Iowa High School Baseball Hall of Fame, though he did not attend high school. Wild Bill had a wild childhood that resulted in two broken arms, two broken legs, and a broken collarbone. All the injuries occurred in separate accidents. A severely broken leg caused permanent damage, which may have caused his future 4-F military status.

In spite of the injuries, young Zuber was strong and fit. He possessed a terrific throwing arm that generated interest beyond the colonies. He tried out for Casey Stengel, then manager of the Toledo Mud Hens, in 1931. The Old Professor later quipped, “Bill Zuber and the strike zone have never been formally introduced.” Yet, the 18-year-old showed enough potential that Stengel called Cy Slapnicka, the Cleveland Indians scout in Cedar Rapids.

The story of Slapnicka’s first encounter with Bill Zuber in May 1932 is legendary, and as likely to be true as similar baseball legends. Dizzy Trout, who never played with Zuber, related the legend at a banquet in January 1968. As reported by Robert Markus in the Chicago Tribune, Trout roasted Zuber, saying, “Zuber was discovered by Cy Slapnicka, the scout who found Bob Feller. He found Bill on a farm and seeing an onion lying on the ground he asked Zuber, ‘Can you hit that barn over there with that onion?’ Zuber picked it up and threw it over the barn.” The former 20-game-winner described Zuber’s major league career, and concluded that Bill returned home after his career and “could still throw an onion over that barn, but you know, in all those years he never did learn how to hit it.” The barn legend was even repeated in a brochure used to promote the restaurant Zuber owned after his playing days.

Slapnicka became friends with the Zuber family and recruited Bill over time. The Amana community voted for “The Great Change” in 1932. The change included adoption of capitalism and acceptance of mass culture. As a “free agent,” Bill Zuber went to work for a meat packer in Cedar Rapids so he could play semi-pro ball. He soon signed a contract with Cedar Rapids in the Three-I League. However, the depression-induced financial collapse of the league, followed by a sore arm, temporarily ended his career in 1933.

The 6’2″ fireballer got another chance when Slapnicka signed him for Cleveland in 1934. He was assigned to Fargo-Moorhead, where he was given the nickname “Goober” for obvious reasons. Zuber was challenged by learning English, learning to throw a curveball, and trying to gain command and control of his pitches. The results were extremely encouraging as he compiled a 16-8 record with 189 strikeouts versus 79 walks in 212 innings for the Northern League champions.

The successful season earned him a jump to New Orleans in 1935, but a 3-8, 5.71, start in 63 innings resulted in a demotion to Zanesville. There, he improved to 8-6, 3.15 in 131 innings. However, the strike zone remained elusive: he walked 129 batters for the season.

In 1936, Zuber spent most of the season with Zanesville again, this time pitching just 27 innings for New Orleans. He won 17 and lost 8 with a 3.82 earned run average at Zanesville. He whiffed 208 batters and hurled 22 complete games. The highlight of his season was pitching a no-hitter. The season was good enough to merit a cup of coffee with the Indians. In his major league debut September 16, Zuber allowed two hits and 10 walks in 4 2/3 innings. The results could have been blamed on nervousness or pitching in the rain. He won his second start, but walked another five hitters.

Zuber continued to be wild and erratic with the Double-A Milwaukee Brewers in 1937. He went 15-11, 4.79, with a 101:146 strikeout:walk ratio in 250 innings. Zuber was a regular victim of insults from his teammates, possibly because he was an unsophisticated country boy, and possibly because of his limited command of English and thick accent. He learned to take the jabs and dish them back as well. The male bonding rituals had to have been an adjustment for someone raised in a communal environment. Still, Bill continued to find a home in both worlds, as he went back to the family farm every winter.

Except for 10 games with Milwaukee in 1938 and 13 games with Buffalo in 1939, Zuber spent the 1938-1940 seasons in a mop-up role with Cleveland. He was so rarely used that his high totals for the three years were 17 games in ’40 and 31 2/3 innings in ’39. Young power pitchers often take time to find control or a second effective pitch, but work is necessary, too. Yet, with ERAs and walk ratios over 5.00 each season, Zuber didn’t do enough to convince manager Ossie Vitt that he should be used more. Also, the Indians had a promising pitching staff that improved to second in league ERA in 1939 and first in 1940. Zuber’s most memorable professional event during his years in Cleveland was beaning Ted Williams in a minor league game in 1938. The highlight of his personal life was marrying Connie Moershel of Homestead, one of the Amana colonies, on October 13, 1939.

Vitt didn’t like Zuber, whom he called “Scatter-arm,” or his other players, either. The disrespect was mutual, but a player revolt during the 1940 season failed to remove Vitt. Nevertheless, Vitt was fired after Cleveland failed to win the pennant. The change in Indians management failed to improve Zuber’s situation there. He was sold to the Washington Senators for the $7,500 waiver price late in spring training of 1941. The capitol club was the only one to submit a waiver claim.

The Washington Post account of the transaction was unflattering: “Bucky Harris‘ frantic search for a relief pitcher yesterday netted the Washington club Bill Zuber, tall, hard-throwing right-hander who for eight years has been an unspectacular chattel of the Cleveland Indians.” The article concluded, “Cleveland Managers have been bearing with Zuber since he first joined the club in 1936… chiefly because of the speed he owns. Wildness, however, has been a consistent trouble of Zuber.”

The move to a non-contender gave Zuber an opportunity to pitch more, especially in the second half of the season. Although his performance in mop-up roles was no better than in Cleveland, Zuber made the first of seven starts June 28. Manager Bucky Harris proclaimed, “I’m giving Zuber a chance for his white alley. Every other man on this club has had his starting chance except Bill.” Zuber went all the way in a 3-1 win over the Red Sox. He yielded nine hits and four walks, but the Senators turned five double plays, demonstrating the benefits of a hard sinker. The Red Sox got most of their hits on curveballs, and the walks weren’t too bothersome, considering he hadn’t pitched in three weeks before the start.

Washington Post staff writer Shirley Povich either disrespected Zuber as a player or had an unexplained personal dislike for the friendly Iowan. Povich described him as a “dismal flop” and a “non-entity.” The characterizations were unduly harsh relative to Zuber’s two-year performance for teams finishing next-to-last. The headline of Povich’s June 29 column referred to Zuber as “Misfit.” In Zuber’s next start, he pitched well until the ninth inning when gave up three runs to allow a 6-6 tie and send the game to extra innings.

Zuber’s 6-4, 5.42 line suggests a minimal contribution to the ’41 Senators, but Bucky Harris asserted, “When Bill Zuber joined the Senators, he and he alone did more to boost the team’s morale and confidence than I did.” Although Zuber could be unintentionally funny due to language difficulties, he displayed a quick wit and mastery of self-deprecating humor. A typical example occurred when he was with the Indians. Zuber was called into a game with the bases loaded and no out. He gave up a triple, then walked the next two batters. That caused Vitt to call for another reliever. As he handed the ball to his successor, Zuber quipped, “Here you are. I’m turning the job over to you just like I found it.” While pitching for the Senators against the Yankees, Zuber gave up a home run to Joe DiMaggio. The unhappy pitcher stewed on the mound, drawing out Harris and eventually the umpire. Zuber said, “Damn, they ought to change the rules on a hit like that. A ball hit like that was always an automatic out when I played at home in Amana.”

Bill and Connie’s first child, Dennis, was born in 1941. The December bombing of Pearl Harbor changed baseball as much as it did the rest of American life. Teams began losing players to military service in ’41, and the attack caused many players, including stars, to enlist. Many other players, such as Bill Zuber, were fit enough to be professional athletes, but had physical conditions that rendered them unfit for military service.

Zuber’s role with the Senators did not increase in 1942, but playing against diminished competition helped him overpower more hitters. He finished 9-9 and lowered his ERA to 3.84 despite walking 5.83 hitters per game. He expanded his repertoire when Dutch Leonard taught him a change-up.

Zuber was the victim in a bizarre play in a game against Boston on May 31. He led-off the fifth inning by hitting a double. The next batter hit a foul into the stands. At that time, fans were asked to return balls hit into the stands. In this case, the fan who got the ball wanted to keep it. The other fans booed. In the ensuing confusion, Johnny Pesky pulled the hidden ball trick and tagged out Zuber. On September 5, in what he later described as his biggest thrill in baseball, Bill shutout the Yankees, 1-0, in the nightcap of a double-header.

Following the season, American League umpire Art Passarella told a Los Angeles Times reporter that Zuber was the fastest pitcher he had seen in the AL that year. Joe Cronin said, “I’ve never seen anyone faster, and that includes Bob Feller.” In July, Ted Williams told Shirley Povich, “There were a couple of other fellows who looked faster to me than Feller. One of ’em was Bill Zuber. For a couple of innings, Zuber could blow your head off with his fast one.” According to Russ Hodges in Baseball Complete (1952), Spud Chandler (who taught Zuber to throw a slider in 1946) also said that Zuber could throw harder than Bob Feller. By these accounts and primitive measurements of Feller, we can presume that the Amana native threw close to 100 miles per hour, and perhaps regularly reached the three-digit mark. In The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers, Bill James rates Zuber as having the sixth best fastball of the 1940-1944 era. James notes that control is what makes a fastball useful, but states that was not a major criterion for making the list. Usually, pitchers with upper-90s fastballs have very high strikeout ratios, regardless of their effectiveness. Bill Zuber only struck out 4.39 batters per nine innings in his career. That figure was better than the league average for his era, but well below most dominant-but-wild flamethrowers. As happens so frequently in baseball, this could be a case of perception contradicting a method of numerical measurement.

The Senators had long coveted young Yankees’ second baseman Jerry Priddy, who could not displace Joe Gordon in New York. Accordingly, Zuber and what Washington owner Clark Griffith described as “a lot” of cash were sent to New York for Priddy and prospect Milo Candini. Zuber was a father and classified 4-F, assuring his availability. The deal was consummated January 29, 1943. The promising Priddy went on to play seven solid seasons as a regular in the American League. Candini had a spectacular 7-0 start and an impressive 11-7, 2.49 rookie season for the Senators, who finished a distant second to the Yankees. He hit the sophomore jinx in 1944 and never rebounded after a military stint.

Zuber was successful enough in the Bronx to even the trade. He went 8-4, 3.89 in 1943, but was only given 13 starts and seven relief appearances, as the Yankees top five pitchers all had ERAs well under 3.00. On August 14, the sidearmer pitched a two-hitter against the Browns, but walked five. Back-to-back errors by Ken Sears and Frankie Crosetti cost him the shutout. On October 4, Bill pitched five no-hit innings in the final game of the regular season, yet he was bypassed in the World Series.

Zuber’s usage in 1944 (5-7, 4.21) and 1945 (5-11, 3.19) was nearly identical to 1943. On August 16, 1944, Zuber pitched a three-hitter to lead the Yankees to a 3-1 win, despite making his first start in three weeks. Two weeks later, manager Joe McCarthy said, “I have been puzzled by a lot of pitchers in my time but never quite so thoroughly as by Bill Zuber.” The manager concluded, “Zuber has tremendous lots of stuff and is as fast as anybody. What’s the answer?” New York finished second.

In 1945, Zuber set a Yankees record that is still standing 60 years later: he lost seven shutouts. His bad luck during those Yankee years was typified by his September 13 start. He hurled a no-hitter for 6 2/3 innings, and had a one-hit shutout through nine innings, but his teammates couldn’t score. Zuber ran out of gas in the tenth, and the White Sox won, 7-0. Although he was a lifetime .135 hitter, Zuber had a few key hits in his career. He singled in the winning run during a relief appearance against the Browns June 26. The Bombers finished fourth in ’45. Zuber lost five games to the pennant-winning Tigers. Bill and Connie’s daughter, also named Connie, was born in 1945.

Zuber made only three relief appearances for the Yankees in 1946 before he was sold on waivers to the Boston Red Sox on June 18. Just five days later, he pitched a three-hit shutout against the Indians in his first of seven starts for Boston. On August 31, he smacked a solid single to center field with the bases loaded to drive in two runs in a 4-2 victory over the Athletics. Ted Williams stole the media attention in that game by failing to run out a slow ground ball to short and then arguing with manager Joe Cronin about it.

Bill pitched the best ball of his career for Boston in 1946 (5-1, 2.54) and contributed to the team winning the pennant. Control remained a problem, as demonstrated by his 6.19 walk ratio, but he only allowed 5.88 hits per game, which was by far his best performance. He was used in a mop-up role in his only World Series appearance.

In 1947, Zuber started only one game and was ineffective in relief. A dislocated shoulder destroyed his season. In October, Boston assigned his contract to AAA Louisville after he cleared waivers. Although he would be 35 in ’48, Zuber believed he could still pitch. He appealed to Joe McCarthy, his manager in New York, who had just taken over the helm for Boston, but with no luck.

Zuber missed spring training in 1948 while trying to get a major league deal. He finally reported to Louisville, where he compiled a 4-8 mark with a 6.09 ERA in an inglorious end to his career. His cumulative minor league record was 71-58 with a 4.61 ERA. He was 43-42 with a 4.28 ERA in the majors. Zuber would have liked to remain in the game in some capacity, but did not get an offer.

Bill and Connie bought the Homestead Hotel in Amana from its retiring owners. They renovated the restaurant and reopened it as Bill Zuber’s Dugout in mid-’49. The new owners served as host and hostess and engaged in all aspects of running the business, even growing some of their own food. The restaurant was filled with photographs and other memorabilia from Zuber’s career. The Zubers offered German specialties and popular American fare.

In spite of the demanding requirements of their business, the Zubers enjoyed time with their children, and later, grandchildren, and went to Florida for vacations. Bill enjoyed attending old-timer games, and the Zubers remained fans of baseball at all levels. His final highlight was participating in the Yankee Stadium fiftieth anniversary celebration in 1982. He died November 2 of that year.

Zuber’s family continued to operate the popular restaurant until 1998. Its location near Interstate-80 made it a popular stop with travelers and tourists. According to the September/October 1987 issue of Mother Earth News, the Amana colonies were Iowa’s most popular tourist attraction. The “Field of Dreams” in Dyersville may have superseded it in the years since.

“Bill Zuber” is the wrong answer to several trivia questions. In “The Ballplayers: Baseball’s Ultimate Biographical Reference,” Jack Kavanagh’s entry about Zuber incorrectly states, “He is the only Amish player in major league history.” Although the Amana colonists of Iowa and the Pennsylvania Dutch people shared similar puritanical beliefs and separatist cultures, the two groups are unrelated. Also, Zuber does not hold the final spot in alphabetical lists of ballplayers. George Zuverink is last among pitchers, and Dutch Zwilling is last on baseball’s all-time roster. Jon Zuber, who had a couple of cups of coffee with the Phillies in the late-1990s, is no relation.

Of all the Caucasian males born in the United States in the twentieth century, Bill Zuber was one of the least likely to have a major league career. He had no exposure to baseball during his formative years. His reckless youthful behavior resulted in a slew of broken bones. His limited education came from a society that didn’t need to teach him the English language or the realities of the world beyond the Amana colonies. He was signed to a pro contract simply because he had the raw ability to fling a baseball about 100 miles per hour and make the ball sink. Zuber overcame all that to spend most of 10 seasons in the major leagues and pitch for two pennant winners.

Sources

Books

Charles C. Alexander, Baseball in the Depression Era (Columbia University Press, 2002).

Cliff Trumpold, Now pitching: Bill Zuber from Amana (Lakeside Press, 1992).

Bill Nowlin, Mr. Red Sox: The Johnny Pesky Story (Rounder Books, 2004).

Bill James and Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers: An Historical Compendium of Pitching, Pitchers, and Pitches (Fireside, 2004).

Mike Shatzkin, ed., The Ballplayers: Baseball’s Ultimate Biographical Reference (Arbor House/William Morrow, 1990).

Interview

Connie Gougler, great-niece of Bill Zuber

Newspapers

Shirley Povich, “Zuber Stops Yanks, 1-0, After Nats Lose, 6-2; ‘Last-Hope’ Hurler Gives Five Hits; Leonard Downed by Bunts in Opener Nats Bow, Then Defeat Yanks, 1-0 ,” Washington Post, Sept. 6, 1942.

“Senators Buy Pitcher Zuber” New York Times, Apr. 22, 1941. p. 28.

Tom Fruehling, “You won’t leave Zuber’s hungry,” The Gazette, Dec. 7, 2002.

“Nats Buy Bill Zuber, Tribe Relief Hurler; Waiver Price Brings Right-Hand Speedball Veteran,” Washington Post, Apr. 22, 1941, p. 23.

“Bill Zuber Gets Starting Chance Against Red Sox,” Washington Post, June 28, 1941, p. 14.

Shirley Povich, “‘Misfit’ Wins His Debut As Starter; Nats’ Infield Clicks With 5 Double Plays; Errors Help Winners To Take Early Lead Nats Beat Boston, 3 to 2, Behind Zuber,” Washington Post, June 29, 1941, p. S1.

Shirley Povich, “This Morning; with Shirley Povich,” Washington Post, June 22, 1942, p. 16.

Shirley Povich, “This Morning; with Shirley Povich,” Washington Post, July 7, 1942, p. 18.

“Umpire Passarella Lauds Phil Rizzuto for ’42 Play,” Los Angeles Times, Nov. 25, 1942, p. A9.

Shirley Povich, “Candini Also Acquired in Player Swap; Griff Gives Hurler, Cash to New York Club for Infielder, Newark Pitcher,” Washington Post, Jan. 30, 1943, p. 10.

Louis Effrat, “Yanks Down White Sox With Help of Four Errors; Mcarthymen Get 3 Hits, But Win, 5-2 Misplays, Two by Appling, and Passes Hurt Wade — Zuber Allows Four Blows Hemsley Bats In Three Yankees Break Tie in Sixth and Score Twice More on White Sox in Eighth,” New York Times, July 27, 1943, p. 10.

James P. Dawson, “Zuber of Yankees Beats Browns, 2-1, with Two-Hitter,” New York Times, Aug 15, 1943, p. S1.

James P. Dawson, “Zuber’s Hit Beats Browns for Yanks,” New York Times, June 27, 1945, p. 23.

“Zuber Hurls 1-Hitter for 9 Innings,” Washington Post, Sept. 14, 1945, p. 16.

“Red Sox Acquire Zuber,” New York Times, June 19, 1946, p. 34.

“Red Sox Overcome Indians by 5-1, 6-0,” New York Times, June 24, 1946, p. 24.

Robert Markus, “Sports Trail; Indian Givers Lured by Sports Celebrities,” Chicago Tribune, Jan. 31, 1968, p. C3.

“Zuber’s Pitching and Batting Pace Red Sox to Third in Row Over Athletics,” New York Times, Sept. 1, 1946, p. 72.

Magazines

Mother Earth News, September/October 1987

Web sites

Baseball-Reference.com

Baseball Almanac

BaseballLibrary.com

Iowa Vintage Baseball Diamonds

Other

Amana Colonies Convention & Visitors Bureau

Amana Heritage Society

List Bill Deane compiled of hidden ball tricks

Iowa vintage baseball diamonds identified in 2003 survey conducted by state historical society of Iowa

Bill Zuber’s Dugout brochure

Full Name

William Henry Zuber

Born

March 26, 1913 at Middle Amana, IA (USA)

Died

November 2, 1982 at Cedar Rapids, IA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.