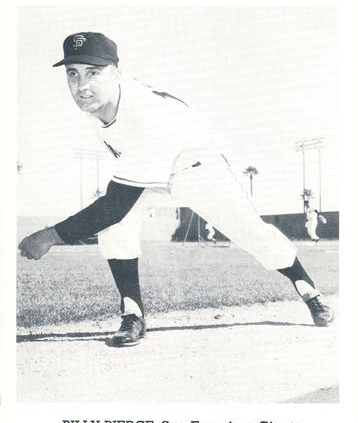

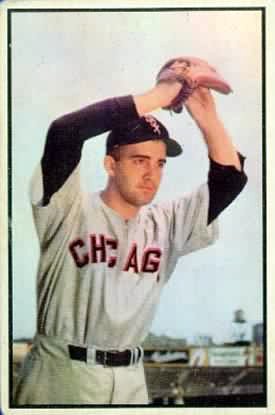

Billy Pierce

Talk about your quick-starting careers.

Talk about your quick-starting careers.

Billy Pierce didn’t play organized baseball until he was 15. Born in Detroit on April 2, 1927, Pierce attended Highland Park (Michigan) High School, but originally he was not a pitcher. As he recalled to Mark Liptak, “I was a first baseman when I was 14, and the kid who was a pitcher on our team left and went to another club because they had better looking uniforms. We were only about a week from starting play in our league and I threw hard, so I became the pitcher. I was wild in those days!”1

In 1944, still only 17, Pierce (whose full name is Walter William Pierce) was chosen as Detroit’s representative in the inaugural All American Boys Game, sponsored by Esquire magazine and played at the Polo Grounds in New York. The two teams were managed by Connie Mack and Carl Hubbell. Also among the nearly 18,000 in attendance were Babe Ruth, Joe McCarthy, and former New York Mayor Jimmy Walker.

And the star of the game? Billy Pierce, a/k/a “Mr. Zero.” From the account in the next day’s New York Times:

In 17-year-old Bill Pierce, a southpaw from Detroit, who, because of the many shut-outs credited to him, is called “Mr. Zero,” Mack was favored with a young hurler with unlimited potentialities.

Pierce, endowed with respect-demanding speed and a sharp-breaking curve, twirled the first six innings for the winning combination, yielded three hits and fanned six. George Worgul of Richmond Hill High School and Mason Leeper of Dallas, N.C., who finished, also were impressive, but neither won the fancy of the crowd as much as Pierce did.2

Pierce picked up the win in the East’s 8-0 victory, along with most-valuable-player honors.

Pierce had already signed with his hometown Tigers, and in 1945 he went to spring training and started the season on the major-league roster (in 1945, there were a great number of very young and very old players on major-league rosters). Pierce later recalled, “For the first six weeks of the season I sat on the Tigers’ bench and didn’t pitch. Then I was sent to Buffalo. I returned to the Tigers before September 1, so I was on Detroit for three-fifths of the year and we won the world championship. I pitched only 10 innings all year and didn’t pitch in the World Series — but I was eligible to pitch and received a ring at the age of 18!”3

In 1946, with the veterans back from the war, Pierce went back to the minors, but pitched only 10 games for Buffalo before hurting his back in June. “I was in the Ford Hospital for a while,” he remembered. “During the winter they would bake me in an oven three days a week. They decided the pain came from my being a boy doing a man’s work. So I rested.”4

In 1947 Pierce returned to Buffalo, where Paul Richards had taken over as catcher-manager. It wasn’t the first time they’d met. Richards later told Donald Honig:

Billy Pierce is quite a pitcher. You know, I first ran into him when I was playing with Detroit in 1945 and he was working out with them. In fact, he got into a few games that year. He was just a kid. His father owned a drugstore about a block from where I was living. I’d go in now and then to buy something, and there was this kid clerking behind the counter. I never paid any attention to him. Then out at the ball park we had this little left-hander who I’d warm up occasionally. One day he walked up to me on the field and said, “You know, you won’t even speak to me when you come into our drugstore.”

“What are you talking about?” I asked.

“That’s my father’s drugstore,” he said. “You were in there last night.”

I took a good hard look at him and, sure enough, he was the clerk.5

Pierce pitched well at Buffalo in ’47 and later said of Richards, “Being with Paul Richards in 1947 was one of the greatest things to happen to me. He didn’t work me too hard because he was afraid of stirring up a back ailment I had in 1946. He nursed me along carefully and even caught me himself in two games when he had a broken finger.”6 Pierce started only 23 games (and relieved in five more), but his 14-8 record and 3.87 ERA were enough to get him back to the majors in 1948, all of which he spent with the big club. But he rarely pitched, just 55 innings in 22 games. And after the season, the shocking news …

In November, I went over to my fiancée’s house. We turned on the radio and I learned from a disk jockey that I had been traded to the White Sox. I was traded for Aaron Robinson and 10 grand because the Tigers wanted a left-handed-hitting catcher who could take advantage of the short porch in right field. The Tigers wanted to give the Sox Ted Gray instead of me, but Chicago wouldn’t go for it. . . . It was a bad shock to be traded from Detroit.7

For the first few years he was in the majors, Pierce — all 5 feet 10 inches and 160 pounds of him — just reared back and threw. And he certainly could throw hard. As Joe DiMaggio supposedly said after batting against Pierce, “That little so-and-so is a marvel. So little, and all that speed. And I mean speed! He got me out of there on a fastball in the ninth that I’d have needed a telescope to see.”8

But early on, the speed was enough only to make Pierce a good pitcher. In 1949 and ’50 with Chicago, he posted better-than-average ERAs (3.88 and 3.98) and won 19 games for a lousy team. But he also walked more batters than he struck out (granted, in that era such a feat was not particularly uncommon). He wasn’t yet a great pitcher.

In 1951, Paul Richards entered Billy Pierce’s life again, this time as the White Sox’ new manager.

Richards got a lot of credit in the 1940s when Hal Newhouser became one of the American League’s best pitchers, and likewise he would get a lot of credit for Billy Pierce’s becoming one of the league’s best pitchers in the 1950s. According to Richards, “I worked a little with him on his windup to help his delivery and convinced him that he had to throw a slider and an occasional change of pace, and that was all he needed.”9

In Richards’ first season in Chicago, Pierce went 15-14 with a 3.03 ERA. The most striking improvement was in his control of the strike zone. In 391 innings over the previous two seasons, Pierce had walked 249 hitters while striking out 213. Under Richards, Pierce’s strikeout rate fell slightly (and temporarily, as it turned out), but his walk rate fell significantly, from one walk every two innings to one walk every three.

Forty years later, Pierce said of his transformation, “I learned to control my fastball better and, at Richards’ request, learned a third pitch to go with my fastball and curve — a slider. Developing the slider helped me tremendously because it gave me a third out pitch. I threw it almost as hard as my fastball, but I could throw it for strikes better than the fastball or good curve. . . . Richards made me work on it, and it took me about two years before it was consistent.”10

Pierce didn’t really begin to refine his slider until near the end of the 1951 season, and the change really showed up in 1952, when he went 15-12 with a 2.57 ERA. Then he got off to a fast start in 1953. He started the All-Star Game that year (and would start in 1955 and ’56, too), and in three innings the only blemish was Stan Musial’s single to center field. He finished that season with 18 wins, and for the first time he led the American League in something (strikeouts, with 186). It wouldn’t be the only time, though. In 1955, he led the league with a 1.97 ERA; he was the only ERA title qualifier from 1947 to 1962 to post an ERA lower than 2.00. In 1957, he led the league with 20 wins. And beginning in 1956, he led the American League in complete games in three straight seasons.

He did all this while pitching for the White Sox. He also threw four one-hitters, and on June 27, 1958, he just missed becoming the first left-handed pitcher in major-league history to twirl a perfect game. Facing the Washington Senators before 11,300 fans at Comiskey Park, Pierce retired the first 26 batters he faced and owned a 3-0 lead with two outs in the top of the ninth inning. But Washington manager Cookie Lavagetto — who, as a pinch-hitter, famously broke up a World Series no-hitter in 1947 — sent up a pinch-hitter, Ed Fitz Gerald, and Fitz Gerald doubled. He then struck out Albie Pearson to end the game.

In 1982 Pierce told sportswriter Bob Vanderberg, “Fitz Gerald was a first-ball, fastball hitter. So we threw him a curveball away. And he hit it down rightfield line for a hit. . . . I didn’t feel that badly about it — really not that badly. It didn’t mean that much — at the moment. In later years, I wished probably that it had happened. It would’ve been nice if it had happened.”11

The 1958 season (17-11, 2.68 ERA) would be Pierce’s last great one. In ’59 his ERA jumped nearly a full run, to 3.62, and he went 14-15. Most disappointingly for Pierce, after starting 33 games during the regular season, he wasn’t given a single starting assignment in the World Series, instead pitching four (scoreless) relief innings.

Why didn’t Pierce start in the Series? Early Wynn started three games, which made sense because Wynn had won 22 games during the season. Bob Shaw started twice, which made sense because he’d gone 18-6 with a 2.69 ERA during the season. The other start went to Dick Donovan, who’d gone 9-10 with a 3.66 ERA.

There are two obvious questions: 1) Why did Donovan start instead of Pierce; and 2) While starting Wynn three times wasn’t odd in those days, why did he make his third start on just two days’ rest? Wynn’s second start, in Game Four, ended abruptly in the third inning, undone by five consecutive miscues and three errors. When he was yanked by manager Al Lopez, he’d probably thrown between 50 and 60 pitches. Today, you wouldn’t see a pitcher come back and start three days later. But things were different 50 years ago, and Wynn was one of the toughest customers around.

As for why Pierce didn’t start Game Three in Los Angeles, David Gough and Jim Bard quoted White Sox vice president Chuck Comiskey in their book Little Nel: The Nellie Fox Story:

Charles Comiskey had hoped, and even appealed to Lopez, to give Billy Pierce a start in the Series. “Lopez wanted to pitch righthanders against the Dodgers in the Coliseum because of their strength from the right side of the plate. I can’t deny that, but Pierce had been such a great pitcher for the White Sox for so many years that I felt he deserved a shot. I said, ‘Al, please pitch Billy.’ He said, ‘I can’t.’ I was disappointed, but I didn’t interfere with the field manager.”12

So Dick Donovan — rather than Pierce — had started Game Three. And he pitched well; when he left with two outs in the seventh, the score was still 0-0. Donovan did get the loss after his relief gave up a two-run single. But considering that the White Sox scored only one run in the game — the final score was 3-1 — it’s hard to blame the loss on Donovan.

Many years later, White Sox outfielder Al Smith told interviewer Danny Peary, “I was surprised that Al Lopez didn’t start Billy Pierce. We all knew why Lopez didn’t pitch him, but we never told anyone and I won’t say now.”13

Maybe it’s not really so complicated. For his part, Pierce blamed a hip injury that cost him three weeks late in the season. “And then, when the World Series came about,” Pierce told interviewer Mike Mandel, “Lopez didn’t figure that I’d recovered well enough to start, so I just relieved. . . . [H]e didn’t figure that the hip would hold up.”14

(Coincidentally or not, shortly before going on the disabled list with the hip injury, Pierce had pitched 16 innings in a 1-1 tie against the Orioles. He didn’t last more than four innings in either of his next two starts, then was out of action for three weeks.)

Al Smith’s support isn’t surprising, because Pierce was as well-liked as anyone on the team. He didn’t drink but once said, “If another player wanted to drink, fine. I could go along and have a Coke. I never had problems with other ballplayers, where if I didn’t drink I wasn’t part of the group. They understood that I’d rather be at the movies.”15

Pierce and Nellie Fox, his longtime roommate, were considered the leaders on the club, and Pierce was for years the White Sox’ union player representative. Later Pierce pitched for San Francisco, and Giants pitching coach Larry Jansen said about him, “Never had a bad word about anybody — the nicest man you’d ever want to meet.”16

Oddly, after winning 14 games with a 3.62 ERA in 1959, Pierce won 14 games with a 3.62 ERA in 1960. And a worrying trend continued. After leading the American League in complete games in 1956, ’57, and ’58, Pierce had completed only a dozen of his starts in 1959 (still eighth most in the league), and in ’60 he completed only eight starts and his innings fell below 200 for only the second time since 1949. In 1961, he started only 23 games, his fewest since joining the White Sox.

The word around the American League was that Pierce was damaged goods, that his hip injury was chronic and that his sore shoulder wasn’t going to get better. On November 30, 1961, the White Sox traded Pierce and Don Larsen to the Giants for pitchers Eddie Fisher and Dom Zanni and outfielder Bob Farley. Pierce, perhaps still hurting from the 1959 Series, said, “I am not surprised. But it’s a rotten trick and I will make Al Lopez sorry he did it.”17

In the spring of 1962, Pierce pitched like a man with a hip injury and a sore shoulder. Nevertheless, he broke camp with a slot in the rotation, and in his first start he beat the Cincinnati Reds, 7-2. Pierce also won his second decision, and his third, and he just kept on winning, running his record to 8-0 in his eighth start, on June 1, before finally losing a close one (4-3) to the Chicago Cubs on June 7. Pierce’s luck was even worse in his next start. Pitching against the Reds in Cincinnati, he was spiked in the first inning and wound up taking a dozen (or more) stitches. He next pitched on July 15, got hammered in three-plus innings, and didn’t start again until August 2, when he re-assumed his spot in the Giants’ rotation.

Maybe all that rest helped him. On September 26, the last scheduled Wednesday of the regular season, Pierce beat the St. Louis Cardinals to keep the Giants two games behind the first-place Los Angeles Dodgers. On Thursday, both contenders lost. On Friday, the Dodgers lost to the Cardinals and the Giants were rained out. On Saturday, the Dodgers lost again and the Giants split a doubleheader with Houston. And finally, on Sunday the Dodgers lost, 1-0, and the Giants won, 2-1, leaving the contenders tied at the conclusion of the schedule. Just as in 1951, the clubs would play a best-of-three playoff series to decide the National League pennant.

The Giants that season had an odd pitching staff. Among the four pitchers who started more than 15 games, nobody had an ERA higher than 3.53 (Billy O’Dell) or lower than 3.36 (future Hall of Famer Juan Marichal). In the middle were Pierce (3.49) and Jack Sanford (3.43). The playoff series would begin on Monday, October 1, the day after the season ended. Sanford and Marichal had started in the Saturday doubleheader, O’Dell on Sunday.

That left Billy Pierce to face Sandy Koufax, who’d missed most of the last two months of the season with a gruesome hand injury but finished with the lowest ERA (2.54) in the National League. Koufax still wasn’t really healthy enough to pitch but it probably wouldn’t have mattered, as Pierce pitched a three-hitter to shut out the Dodgers, 8-0 (and run his Candlestick Park record to 12-0). By most accounts, Pierce was relying on slow stuff by the time he joined the Giants, but he could still throw hard when he wanted to. Watching that first playoff game from the press box, longtime National League umpire Babe Pinelli exclaimed, “Look at him fire that fast one! He’s been in so many clutch games that they’re nothing to him!” 18 (According to Pierce, his fastball was still his best pitch.)

The playoff series moved south to Dodger Stadium for the second game. The Giants were ahead 5-0 in the sixth inning, but the Dodgers exploded for seven runs to take the lead, then scored once in the bottom of the ninth to break a 7-7 tie and force a third game.

What followed was a near-replay of what had happened 11 years earlier between the same two teams (but on the other side of the continent). Just as they had in the third playoff game in 1951, the Dodgers led after eight innings. And just as they had in 1951, the Giants jumped ahead in the ninth. But this time the Giants were the road team, so the Dodgers would have one last chance. Juan Marichal had pitched the first seven innings for the Giants, and was replaced by Don Larsen in the eighth. Larsen was bumped in the top of the ninth for a pinch-hitter.

Pierce had pitched a complete game just two days earlier, but now Giants manager Alvin Dark called on his 35-year-old lefty once more. He retired the Dodgers in order, and the Giants, 6-4 victors, were the National League champions. “It was the biggest thrill of my life, getting those batters 1-2-3,”19 Pierce told Danny Peary. Lee Walls made the final out, lifting an easy fly ball to center field. Just before making the catch, Willie Mays reminded himself to save the ball for Pierce. But the moment got the better of him and he “changed his mind and heaved it into the center-field bleachers in a cathartic act of pure, unadulterated ecstasy.”20

Pierce pitched well against the Yankees in the ensuing World Series. He tossed six shutout innings in Game Three before faltering in the seventh, then beat the Yankees 5-2 with a three-hitter in Game Six. The Giants lost Game Seven, of course, but Pierce was one of the big stories that fall. Including the playoff series against the Dodgers, Pierce pitched in four postseason games, won two of them and saved another, posted a 1.44 ERA, and allowed only 11 hits and three walks in 25 innings.

In the Giants’ 1963 home opener, Pierce ran his Candlestick Park winning streak to 14 straight (including the World Series), tossing a shutout against Houston. (According to Charles Einstein, Pierce got some help in his home games. In Willie’s Time, Einstein wrote that Giants groundskeeper Matty Schwab had a habit of “wetting down the grass on the left side of the infield hours before game time on days when Pierce was scheduled to pitch. This had the effect of slowing down ground balls that righthanded batsmen would get off lefthanded pitching, reducing the number of hits that would go through to the outfield.”21)

The streak finally ended four days later with a 4-0 loss to the Cubs. And it was all downhill from there. Pierce finished 1963 with 3 wins, 11 losses, and a 4.27 ERA, his highest since he was a rookie in 1948.

In December the Giants waived Pierce, soon to be 37 years old. He wanted to keep pitching and thought he would, saying, “I’m sure there is at least one big-league team that wants me.”22 There was; Pierce again went to camp with the Giants, earned a roster spot and signed a new contract on Opening Day. But Bobby Bolin was ready for a spot in the rotation and the Giants had traded for Bob Hendley, who had good stuff and was a dozen years younger than Pierce. So the veteran lefty coming off a lousy season went to the bullpen and pitched effectively (2.20 ERA), though rarely in key situations (four saves, two wins, zero losses in relief).

On September 10, he started for the first time in more than a year, and beat the Dodgers with 7⅔ strong innings. Afterward, somebody asked him if he knew how many strikeouts he had. “Right to the dot,” he replied. “I had 1,994 going into the game. I added three more and that leaves me three short of the 2,000 mark.”23 But Pierce wouldn’t get another start, and in fact would pitch just once more. On October 3, the next-to-last day of the season, he picked up two K’s in three innings of relief, which left him just one short of 2,000 career strikeouts (and in 15th place on the all-time list at the time, between Hall of Famers Dazzy Vance and Red Ruffing).

And that’s where Pierce’s quest ended. Though he’d gone 3-0 with a 2.20 ERA in ’64, he announced his retirement on the season’s final day. “My children were growing up and I wanted to be with them,” Pierce told Mike Mandel. “I didn’t want to be traveling all over the country all the time.”24 He finished his 18-year major league career with 211 victories, 169 losses, and an ERA of 3.27.

Billy and his wife, Gloria (known as Goldie), were married in 1949 and had three children, sons William and Robert and daughter Patti. Before his last year with the Giants, Pierce had moved his family back to the Chicago area. He co-owned an Oldsmobile and Cadillac dealership there for two years, worked briefly as a stockbroker, and occasionally served as an unofficial scout for the White Sox (he’s been credited with discovering Ron Kittle). In the early 1970s, Pierce caught on with the Continental Envelope Company, and worked for the company in sales and public relations for 23 years before retiring in 1997.

Also in 1997, the Nellie Fox Society — of which Pierce was a member in good standing — saw its namesake inducted into the Hall of Fame. The organization was promptly renamed the Billy Pierce Society. Ten years later, Pierce was at U.S. Cellular Field for the unveiling of a bronze sculpture in his likeness on the center-field concourse, joining Carlton Fisk, Minnie Minoso, and his 1959 teammates Fox and Luis Aparicio. He died of gallbladder cancer on July 31, 2015. Said White Sox chairman Jerry Reinsdorf in tribute to Pierce: “He epitomized class, not just as a ballplayer on those great Go-Go White Sox teams of the 1950s, but as a gentleman and as a human being who devoted so much of his life to helping others.”25

This biography appears in “Go-Go To Glory: The 1959 Chicago White Sox” (SABR, 2019), edited by Don Zminda.

Notes

1 Mark Liptak, “Flashing Back with Billy Pierce,” http://www.whitesoxinteractive.com/rwas/index.php?category=11&id=1546

2 Louis Effrat, “East’s Nine Wins In Boys’ Game, 6-0,” New York Times, August 8, 1944.

3 Danny Peary, editor, We Played the Game: 65 Players Remember Baseball’s Greatest Era, 1947-1964 (New York: Hyperion, 1994), 48.

4 Ibid., 48.

5 Donald Honig, The Man in the Dugout: Fifteen Big League Managers Speak Their Minds (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1977), 137-38.

6 Bruce Jacobs, Baseball Stars of 1957 (New York: Lion Library Editions, 1957), 142.

7 Peary, 81.

8 Bill James and Rob Neyer, The Neyer-James Guide to Pitchers: An Historical Compendium on Pitching, Pitchers and Pitches (New York: Fireside, 2004), 104.

9 Honig, 138.

10 Peary, 168.

11 Bob Vanderberg, Sox: From Lane and Fain to Zisk and Fisk (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 1984), 142.

12 David Gough and Jim Bard, Little Nell: The Nellie Fox Story (Bend Oregon: Maverick Publications, 2000), 208-09.

13 Peary, 458.

14 Mike Mandel, SF Giants: An Oral History (Santa Cruz: Mike Mandel, 1979), 108.

15 Peary, 105.

16 David Plaut, Chasing October: The Dodgers-Giants Pennant Race of 1962 (South Bend, Indiana: Diamond Communications, 1994), 126.

17 James-Neyer, 106.

18 Ibid., 106.

19 Peary, 540.

20 Ibid., 186.

21 Charles Einstein, Willie’s Time: A Memoir (New York: J.P. Lippincott Company, 1979), 163-64.

22 “Pierce Let Go By Giants, Certain He Can Still Win,” The Sporting News, December 14, 1963: 17.

23 “Pierce Knows Exact Major Whiff Total — Just Three Short of 2,000,” The Sporting News, September 26, 1964: 17.

24 Mandel, 112.

25 Fred Mitchell and Paul Sullivan, “Former White Sox Great Billy Pierce Dies,” Chicago Tribune, July 31, 2015.

Full Name

Walter William Pierce

Born

April 2, 1927 at Detroit, MI (USA)

Died

July 31, 2015 at Palos Heights, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.