Bob Uecker

When Bob Uecker was sent down to the minor leagues in 1961 after breaking camp with the Milwaukee Braves, manager Charlie Dressen told him, “There is no room in baseball for a clown.” 1 Dressen could not have been more wrong. While no one would dispute that professional baseball is a business, Bob Uecker has spent more than a half-century in the game reminding us that the national pastime should also be about fun. “Mr. Baseball,” as he is known to both casual and diehard baseball fans alike, has been a player, broadcaster, coach, actor, all-around ambassador for the game, and, yes, comedian. Beloved for his self-deprecating humor, he would be the first person to make fun of his rather unremarkable playing career, particularly his offensive statistics. “Uke,” Sports Illustrated’s William Taaffe once said, “is the man who made mediocrity famous”. 2

When Bob Uecker was sent down to the minor leagues in 1961 after breaking camp with the Milwaukee Braves, manager Charlie Dressen told him, “There is no room in baseball for a clown.” 1 Dressen could not have been more wrong. While no one would dispute that professional baseball is a business, Bob Uecker has spent more than a half-century in the game reminding us that the national pastime should also be about fun. “Mr. Baseball,” as he is known to both casual and diehard baseball fans alike, has been a player, broadcaster, coach, actor, all-around ambassador for the game, and, yes, comedian. Beloved for his self-deprecating humor, he would be the first person to make fun of his rather unremarkable playing career, particularly his offensive statistics. “Uke,” Sports Illustrated’s William Taaffe once said, “is the man who made mediocrity famous”. 2

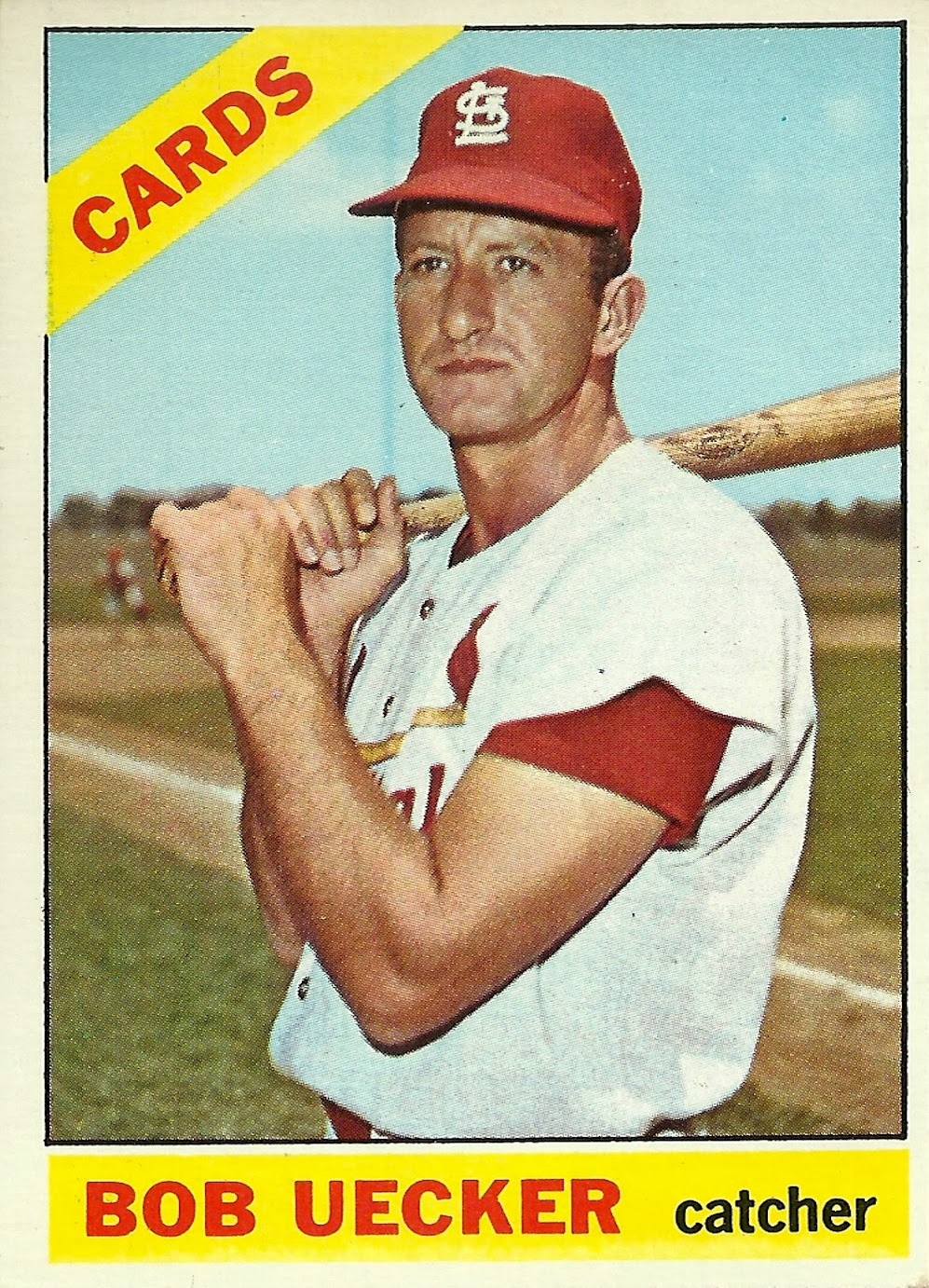

In six seasons (1962-67) as a major-league catcher (almost all of it as a backup), Uecker batted exactly .200. In 297 games (217 starts) he got 146 hits, hit 14 home runs, and drove in 74 runs. “Anybody with ability can play in the big leagues. … But to be able to trick people year in and year out the way I did, I think that was a much greater feat,” he once said.3 In truth, he was a solid defensive catcher, with a career fielding percentage of .981. He played for the Milwaukee/Atlanta Braves, St. Louis Cardinals, and Philadelphia Phillies. In the Cardinals’ world-championship season of 1964, he was the backup to Tim McCarver. He did not play in the World Series. In 2003 he was honored by the Baseball Hall of Fame with the Ford C. Frick Award, presented annually to a broadcaster.

The first Milwaukee native to be both signed and traded by the Braves, Uecker joked that the highlight of his major-league career was when he “walked with the bases loaded to drive in the winning run in an intersquad game in spring training.” 4 Another time he said of his career highlights, “I had two. I got an intentional walk from Sandy Koufax (He also hit a home run; both came on July 24, 1965, at Dodger Stadium), and I got out of a rundown against the Mets.” 5 On being intentionally walked by Koufax, he joked, “I was pretty proud of that until I heard that the commissioner wrote Koufax a letter telling him the next time something like that happened, he’d be fined for damaging the image of the game.” 6

Robert George Uecker was born on January 26, 1934, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, although he jokes to the contrary: “My mother and father were on an oleo margarine run to Chicago back in 1934, because we couldn’t get colored margarine in Milwaukee. On the way home, my mother was with child. Me. And the pains started, and my dad pulled off into an exit area, and that’s where the event took place. … There were three truck drivers there. One guy was carrying butter, one guy had frankfurters, and the other guy was a retired baseball scout who told my folks that I probably had a chance to play somewhere down the line.” 7

Parents Gus, a Swiss immigrant, and Mary (Schultz) Uecker, born and raised in Michigan, came to Wisconsin in the 1920s. Gus was a tool and die maker. He played soccer in his native Switzerland. “That’s where I got my talent,” Uecker said. 8Even during the Great Depression, Gus was able to support his wife, son, and two daughters, earning $3 to $4 a day working on cars.9 Uecker called his father a great family man who never let him down. He said, “In the minors, when I was making $250 a month and the money ran out, he was there.”10 Gus had a circulation problem in his legs. The conditioned worsened over the years, and by the end of the 1962 season, his legs had to be amputated. He died a few years later.

Uecker attended a technical high school in Milwaukee, where he played baseball and basketball. He would ride his bike eight blocks to Borchert Field, home of the minor-league Milwaukee Brewers, where he would see his idols Alvin Dark, Johnny Logan, Heinz Becker, and Danny Murtaugh play. He made his baseball team as a pitcher after a scout saw how hard he could throw. The story goes that at the age of 18, he became a catcher when a teammate handed over his gear to him, asking if he could do any better.11 In his joking fashion he gave a different version of his switch: “My first game, my parents and everybody was there, my friends, and the manager came out to take me out of the game. I didn’t want to come out because I was embarrassed. I said, ‘Let me face this guy one more time, because I struck him out the first time I faced him.’ He said, ‘I know, but it’s the same inning. I’ve got to get you out of here.’ And that was my move to catching.”12

Uecker didn’t finish high school and in 1954, at the age of 20, he enlisted in the Army. He hoped to avoid going overseas by playing military baseball with soldiers who had played in the minors or in college. At the time he had done neither, so he made up a college and lied. He claimed he had played at Marquette, given that it was a college in his native Milwaukee. “Marquette didn’t have a team, but they never checked,” he said.13 He played at Fort Leonard Wood in Missouri, and later at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, where he teamed with shortstop and future Cardinals teammate Dick Groat.

Coming out of the service, he signed with his hometown Braves in 1956 for $3,000. “I could have signed with the Phillies or the Pirates. The Yankees were also interested at that time.”14 He bounced around the minors for six years, playing for Braves affiliates at all levels and showing decent batting ability and some power. In 1956, his first year, he played for two teams in Class C, Eau Claire (Northern League) and Boise (Pioneer League). Between the two clubs he hit 19 home runs. Appearing in 53 games for Boise, he also had a .312 average. With Eau Claire, Evansville and Wichita in 1957 he hit 15 homers. He kept moving up the ladder, and with Boise and Atlanta (Southern Association) in 1958, he hit 22 home runs. In 1959 he played for Jacksonville and Wichita, and in 1960 he was with Triple-A Louisville and Indianapolis. He spent 1961 with just one team, Louisville, where he hit .309 with 14 home runs, and began the next season with the Braves.

Uecker made his major-league debut on April 13, 1962, grounding out as a pinch-hitter against the Los Angeles Dodgers’ Don Drysdale at Dodger Stadium. His hometown debut came on April 19 at Milwaukee’s County Stadium. Facing the San Francisco Giants and Juan Marichal, he was the starting catcher, going 0-3 with two strikeouts and a walk. His first major-league hit came on May 3 at Connie Mack Stadium in Philadelphia. He replaced Joe Torre and singled to left off Art Mahaffey.

After a season of backing up Torre and Del Crandall, Uecker finished the 1962 season on a high note. On September 29 he caught Warren Spahn in the left-hander’s 327th victory, which broke Eddie Plank’s record for the most victories by a left-hander. Uecker went 3-for-4 with three singles, driving in two runs in the 7-3 triumph over the Pittsburgh Pirates in Milwaukee. The next day was the last day of the season. Uecker caught again, and his hit first major-league home run, off Pittsburgh’s Diomedes Olivo. Uecker got into 33 games that season and hit .250. He started the 1963 season with the Braves but got into only nine games as the third-string catcher before being sent down in June to Triple-A Denver, where he batted .283 in 52 games.

While Milwaukee manager Bobby Bragan always liked Uecker defensively, catchers Joe Torre and Ed Bailey made him expendable, and on April 9, 1964, he was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals for two minor leaguers, catcher Jimmie Coker and outfielder Gary Kolb. During his two years in St. Louis, Uecker was used sparingly. Neither manager Johnny Keane nor his successor, Red Schoendienst, stuck with him very long. He was pulled if he wasn’t hitting well and generally played only when another catcher was injured or a late-game substitution was made. The primary receiver Uecker backed up during those years was Tim McCarver. Uecker had just 106 at-bats and hit .198 in the World Series season, but McCarver (who also made a successful second career as a broadcaster) praised him for helping to keep the World Series team loose. He said, “If Bob Uecker had not been on the Cardinals, then it’s questionable whether we could have beaten the Yankees.”15

The 1964 National League pennant race was one of the closest and most exciting of all time. After going 21-8 in September, the 93-69 Cardinals finished just one game ahead of both the Phillies and Reds, who along with the Giants were all alive going into the season’s final weekend. Gene Mauch’s Philadelphia team had a 6½-game lead with 12 games remaining, but blew the pennant by losing 10 straight. As for the NL champs, Uecker called them “the loosiest, goosiest team ever to come from ten games behind to reach the World Series”16

McCarver played every inning of the World Series, hitting .478. “Sat my way through it,” Uecker wrote. “Called it from the bullpen. Yankee fans threw garbage at us, and I picked it up and threw it back.”17 Bob did however contribute in his own way, through his usual antics. During pregame ceremonies before Game One in St. Louis, he found a neglected marching band tuba in the outfield. He picked it up and started shagging fly balls with pitcher Roger Craig.

McCarver broke his finger early in the 1965 exhibition season and Uecker was the Opening Day receiver, catching ace Bob Gibson against the Chicago Cubs. The game was the kind of contest Uecker would joke about while doing his post-career shtick. It was a 10-10 tie at Wrigley Field, which didn’t have lights yet, and was called by the umpires after 11 innings on account of darkness. Uecker was injured in the sixth inning after slamming into a wall while attempting to catch a foul ball. He had been picked off trying to steal home the previous inning, apparently crossed up on coaching signs. Gibson had one of the worst outings of his career, going only 3⅓ innings and giving up five runs on six hits. (Future Hall of Famer Steve Carlton made his major-league debut in the game, walking the only batter he faced.)

Uecker hit .228 in 53 games and after the season he was traded to the Phillies with shortstop Groat and first baseman Bill White for catcher Pat Corrales, outfielder Alex Johnson, and pitcher Art Mahaffey. The 1966 season was the closest he came to being a primary catcher. He had 237 plate appearances, platooning with Clay Dalrymple, who had 404 plate appearances. Always quick to discuss his own futility, Uecker summed up his experiences as a hitter for the Phillies: “With Philadelphia, I’d be sitting on the bench and (manager) Gene Mauch would holler down “grab a bat, Bob, and stop this rally.”18

Uecker’s favorite line about his time in Philadelphia was when he was once fined by a police officer for being intoxicated on the street. “They fined me $50 for being intoxicated and $400 for being on the Phillies.”19 “My managers didn’t want me in the game. Heck, they didn’t want me on the bench. Kids ask which club I played for. Nobody, but I sat for a lot.” 20Ironically, his best offensive season was in 1966. As a Phillie, he hit seven of his 14 career home runs while establishing a career high in hits with 43.

On June 6, 1967, Uecker was traded by the Philadelphia Phillies to the Atlanta Braves for utilityman Gene Oliver. The Braves wanted Uecker specifically to catch Phil Niekro’s knuckleball. “I had caught (knuckleballers) Bob Tiefenauer in Milwaukee and Barney Schultz in St. Louis, so I had a basic idea of how to survive back behind the plate.”21 In 59 games he caught for the Phillies he had 25 passed balls, and led the National League with 27 overall. Two weeks after the trade he hit his only major-league grand slam, off Ron Herbel of San Francisco.

During 1968 spring training, Uecker and his Atlanta teammates Deron Johnson and Clete Boyer were involved in a nightclub fight in West Palm Beach, Florida, on March 21, 1968, at the Cock ‘n Bull Restaurant. Uecker was struck on the head with a beer bottle and required 48 stitches to close the wound. On the field he re-aggravated an injury suffered in a motorcycle accident. He was released as a player and coach on April 2. His final major-league game had been on September 29, 1967.

Capitalizing on his gift as a storyteller, Uecker became a public-relations ambassador for the Braves. “I did stand-up, weird and ignorant stuff about my career—anything for a laugh,” he said.22 In 1969 Uecker’s broadcasting career began with WSB-TV, on which he did television work with Ernie Johnson and Milo Hamilton. His career as a personality in television and movies took off after he did an opening act for Don Rickles at jazzman Al Hirt’s Atlanta nightclub.23 Beginning in 1970 Uecker made close to 100 appearances on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show, doing three to five shows a year.24

He said Carson was the first to refer to him as “Mr. Baseball.” Carson “didn’t know that much about baseball but as we went along he let me do whatever I wanted,” Uecker recalled. “As a matter of fact, when I started doing the shows in New York, you get a script to follow and promote whatever you want to talk about. After about the tenth time I did the show Johnny said, ‘Do you need this stuff?’ and I said, ‘No, I thought you did.’ So from then on we pretty much just ad-libbed and went along and whatever he said I just jumped in and went along with it.”25 His on-air relationship with Carson concluded with Carson’s retirement from late-night television in 1992.

As he continued his entertainment career, Uecker was lured back to his native Milwaukee by Brewers owner Bud Selig. The 1970 Brewers were in their inaugural season, a franchise purchased by Selig after the Seattle Pilots went bankrupt after their first season. Uecker initially signed with the Brewers as a scout before becoming the club’s radio voice. “Worst scout I ever had,” Selig said. “We sent him up to the Northern League, and the next thing I know (general manager) Frank Lane comes raging into my office asking what kind of scout I hired. The report was smeared with gravy and mashed potatoes.”26 “Yeah, I did scouting, if you could call it that,” Uecker said. “For every guy, I wrote, ‘Fringe major leaguer,’ so in case he made it nobody could say, ‘How’d you miss that guy?’ ”27

Clearly his talent lay behind the microphone, and on September 4, 1971, the Brewers announced that Uecker would broadcast games on TV and radio. “I’ve never signed a contract with the Brewers since I’ve been broadcasting and I never will,” he said in 1999. “Whatever we agree on, we have a talk and a handshake, and I don’t even think that I have had a handshake the last ten years.”28 On radio station WTMJ he first partnered with friend and colleague Merle Harmon. Tom Collins filled in as well. “Merle Harmon helped me from the start,” Uecker wrote. “I’d never done (radio) baseball when I joined him in the booth, not unless you count my play-by-play into beer cups in the bullpen. Beer cups don’t criticize, [but] people do. … Merle and Tom Collins let me do color, then play-by-play, and saved me if I screwed up.”29

While achieving quick fame as a buffoon on TV, Uecker slowly grew as a play-by-play announcer on radio. “It’s amazing to think of now, given his ability, but Bob’s problem then was in finding stuff to ad-lib,” recalled Tom Collins. “He’d constantly repeat the count and the score, and swing his legs like a pendulum, and smoke cigarette after cigarette.”30 Uecker honed his craft with hard work. “I had everything to learn and I spent ten years learning it. … I didn’t try to wisecrack my way through it.”31 In a rare moments of seriousness, he said he never spoke badly of or criticized a player on the air, reasoning, “I know how hard this game is to play.”32 Uecker, who became the main play-by-play man in 1980, said he preferred radio over television: “You paint a picture in the mind. It’s a kick to make baseball come alive to a guy hundreds of miles away who’s never seen your home park.”33

Uecker was serious behind the mike. The only time he let loose in the booth is in a blowout at Miller Park, said former broadcast partner Jim Powell (1996-2008). “It’s a 9-1 game, that’s when the buttons at home get pushed [off]. That’s when everyone tunes in. … When it’s 9-1, Bob becomes Uke. It’s a lopsided game where he really gets going.”34

While continuing his radio work with the Brewers in the ’70s, Uecker went national and helped telecast play-by-play for ABC Monday Night Baseball from 1976 to 1982. During his tenure there, which included All-Star Games, League Championship Series, and World Series games, he teamed up in the booth with an initial crew of Bob Prince, Warner Wolf, and Howard Cosell. Cosell in particular had great chemistry with Uecker, playing the straight man while Bob was his comedic foil. Cosell once teased him on the air, saying that he didn’t know what the word “truculent” meant. “Sure I do,” Bob said one night in Minneapolis, “If you had a truck and I borrowed it, that would be a truck-u-lent.” Cosell paused and said to the national audience, “Need I say any more?”35

Uecker co-hosted a variety of television shows in the 1970s and ’80s, among them ABC’s The Superstars, Battle of the Network Stars, and Bob Uecker’s Wacky World of Sports. He also appeared in a number of commercials. The ones he is best remembered for were for Miller Beer, both starring himself and as part of the ex-jock Miller Lite All-Stars. In his first ad he appeared outside a tavern only to be locked out because a fan asks him if he is Bob Uecker. In a sequel, he gets into the bar by claiming that he is actually Yankees pitching legend Whitey Ford. “So I lied,” he says as he looks into the camera.36 A popular Ueckerism was born in another Miller ad when he thinks that management has given him the best seats in the ballpark. Ready to sit down close to behind home plate, he is escorted elsewhere by an usher while bragging, “I must be in the front rooow.”37 He has in fact been placed way up in the nosebleed seats, as animated and excited as ever.

While his career as the radio voice of the Brewers continued, Mr. Baseball landed his first major acting gig in 1985. It was a new ABC sitcom about a family in suburban Pittsburgh. Mr. Belvedere was based on a 1949 Gwen Davenport novel, Belvedere, which first was made into films starring Clifton Webb. The small-screen version was similar in story to the Hollywood films. Christopher Hewitt played Lynn Belvedere, who was hired as a nursemaid for the family’s three children. Uecker was the patriarch of the family, a sportswriter named George Owens. “A lot of his character was picked up from my own,” Uecker said.38 To do the show, the Brewers granted him permission to shoot episodes in Hollywood in the late summer and early fall. He continued to make Miller Lite commercials and make appearances on the Tonight Show. He even hosted Saturday Night Live once, on October 13, 1984. Mr. Belvedere was by all accounts a successful show, running for six seasons from 1985 to 1990.

While his career as the radio voice of the Brewers continued, Mr. Baseball landed his first major acting gig in 1985. It was a new ABC sitcom about a family in suburban Pittsburgh. Mr. Belvedere was based on a 1949 Gwen Davenport novel, Belvedere, which first was made into films starring Clifton Webb. The small-screen version was similar in story to the Hollywood films. Christopher Hewitt played Lynn Belvedere, who was hired as a nursemaid for the family’s three children. Uecker was the patriarch of the family, a sportswriter named George Owens. “A lot of his character was picked up from my own,” Uecker said.38 To do the show, the Brewers granted him permission to shoot episodes in Hollywood in the late summer and early fall. He continued to make Miller Lite commercials and make appearances on the Tonight Show. He even hosted Saturday Night Live once, on October 13, 1984. Mr. Belvedere was by all accounts a successful show, running for six seasons from 1985 to 1990.

In 1989 Uecker’s acting career reached new heights when he appeared in the comedy movie Major League, starring Tom Berenger, Wesley Snipes, and Charlie Sheen, with a plot about a woman who inherits the Cleveland Indians from her late husband. She wants to move the team to a warmer climate, yet the only way she can get out of a contract is by fielding a bad team with low attendance. The players foil her plans by making the playoffs. Uecker played the gregarious yet often inebriated team broadcaster Harry Doyle. Many of the film’s scenes were shot in Milwaukee’s County Stadium.

With the release of the film, Uecker made himself a household name while introducing him to a new generation of fans. The Harry Doyle line of “Juuuuuust a bit outside,” which described a wild pitch, became a piece of baseball popular culture. It has become an oft-quoted phrase like “There’s no crying in baseball” (A League of Their Own), or “Chicks dig the long ball” (a late 1990s Nike commercial with pitchers Tom Glavine and Greg Maddux). Uecker reprised his role as Harry Doyle in two sequels. He enjoyed making the first two movies, but as for Major League 3: Back in the Minors, he said, “Three stunk. … It was on airplanes the day after we finished it.”39 Upon the first Major League’s 20th anniversary in 2009, Uecker said, “It seems to be playing more now than when it originally came out. … Every day I run into someone at the ballpark or on the street and they say, ‘Hey, I saw you in that movie … it was on again today.’ I mean, I go into clubhouses all the time and these players today are playing it in clubhouses before the game.”40

At one point Uecker considered leaving broadcasting to concentrate full time on acting, doing commercials, making movies, and appearing on television. It was not helping that Milwaukee was fielding some consistently bad teams. Such an example was the 1984 Brewers, who finished last in the American League East, 36½ games behind the World Series champion Detroit Tigers. In the end he decided to stay put, declaring, “I could have left there a long time ago, but no matter what I do, I’m staying. All the television stuff, the movies, the sitcoms, the commercials, that’s all fun. All I wanted to do is come back to Milwaukee every spring to do baseball.”41

Over the years Uecker has called some of the biggest games in Brewers history. He was behind the mike on July 20, 1976, when former teammate Hank Aaron hit his 755th and final home run. He was there when the “Harvey’s Wallbangers” Brewers clinched their first and only American League pennant in 1982 (The team switched to the National League’s Central Division in 1998), and he called Juan Nieves’ April 15, 1987, no-hitter, as of 2011 the only one in franchise history, and Robin Yount’s 3,000th hit, on September 9, 1992.

In the 1990s, Uecker helped call the 1995 and 1997 World Series on NBC-TV alongside Bob Costas and Joe Morgan. In 2003 he received the prestigious Ford C. Frick Award for Broadcasters, denoted by a plaque at the Hall of Fame. Even in accepting the award he couldn’t resist a few jokes. He thanked all the people he worked with in the booth over the years: “I remember working first with Milo Hamilton and Ernie Johnson. And I was all fired up about that, too, until I found out that my portion of the broadcast was being used to jam Radio Free Europe. And I picked up a microphone one day and it had no cord on it, so I was talking to nobody.”42

He also didn’t forget to thank his family for sticking with him over the years: “My family is here today (Uecker has been married and divorced twice with two daughters, Leann and Sue Ann, and two sons, Bobby Jr. and Steve).43 My kids used to do things that aggravate me, too. I’d take them to the game and they’d want to come home with a different player. “But my two boys are just like me. In their championship Little League game, one of them struck out three times and the other one had an error allowing the winning run to score. They lost the championship, and I couldn’t have been more proud. I remember the people as we walked through the parking lot throwing eggs and rotten stuff at our car. What a beautiful day.”

In addition to winning the Ford Frick Award, Uecker has been named Wisconsin Sportscaster of the Year five times by the National Sportscasters and Sportswriters Association. He was named to the Wisconsin Performing Artists Hall of Fame in 1993 and inducted into the Wisconsin Athletic Hall of Fame in 1998. He was elected into the National Radio Hall of Fame in 2001.

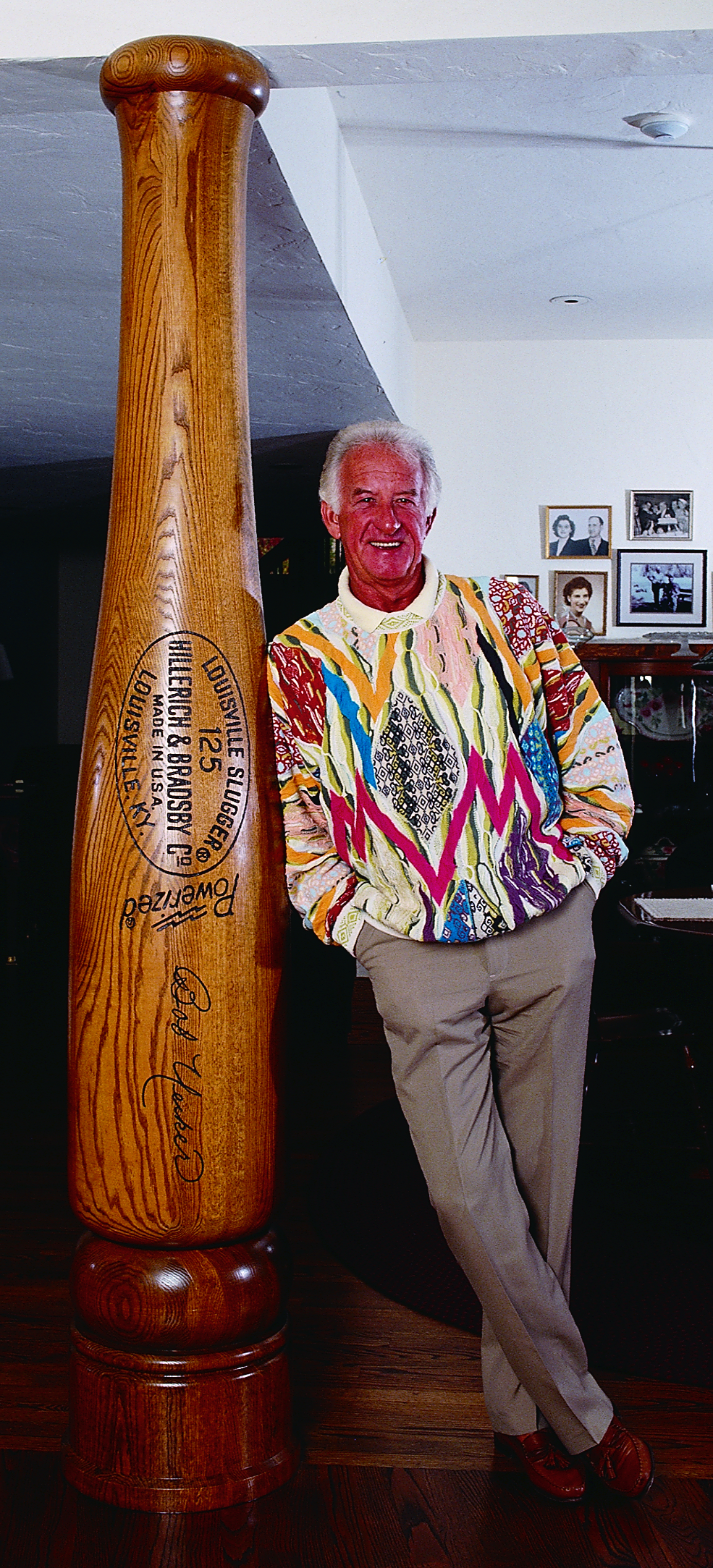

In 2006 Uecker’s 50th year in professional baseball, the Brewers placed a number 50 in their “Ring of Honor,” near the retired numbers of Hall of Famers Robin Yount and Paul Molitor. Three years later, on May 12, 2009, Uecker’s name was also added to the Braves Wall of Honor inside Miller Park. In March 2010, in an honor likely no other major-league baseball player will ever claim, Uecker was inducted into the WWE Wrestling Federation’s Hall of Fame for participating in Wrestlemania III and IV in the 1980s.

Finally, the words of his famous home-run call “Get up! Get up! Get outta here! Gone!’” were inscribed in the lights above Miller Park. Perhaps more fittingly, there are 106 obstructed-view seats in the upper terrace level above home plate that cost only $1 in honor of Uecker’s Miller Lite “Front Row” commercial. As of 2011 he could still be heard calling Brewers games on WTMJ-AM radio with partner Cory Provus. “It’s been great,” he said in a 2005 ceremony marking 50 years in baseball, “I’d like to do this again 50 years from now when I get to 100. Wherever I am, dig me up. Bring me back here. A couple times around the warning track and take me back to the hole where you picked me up.”44

Postscript

Bob Uecker died at the age of 90 on January 16, 2025.

Sources

Statistics and game information found through baseball-reference.com and retrosheet.org.

Photo credits: Courtesy of the Milwaukee Brewers and Trading Card Database.

Notes

1 Bob Uecker and Mickey Herskowitz, Catcher in the Wry: Outrageous but True Stories of Baseball (New York: Jove Books, 1982), 25.

2 Curt Smith, Voices of Summer: Ranking Baseball’s 101 All-Time Best Announcers (New York: Carroll and Graff Publishers, 2005), 269.

3 Uecker and Herskowitz, 4.

4 Curt Smith, Voices of the Game: The Acclaimed Chronicle of Baseball Radio & Television Broadcasting From 1921-Present. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992), 420.

5 Larry Stewart, “Just a Bit Outside the Bounds of Reality,” The Inside Track Morning Briefing, Los Angeles Times, May 23, 2006.

6 “A Life Of Detours: Confessions of a Feather-Hitter,” Christian Science Monitor, July 24, 1961.

7 Uecker and Herskowitz, Introduction.

8 Smith, Voices of Summer: 266.

9 Uecker, Catcher in the Wry, 12.

10 Uecker, Catcher in the Wry, 12.

11 Michael Hiestand, “Broadcaster spin years: Punchless former catcher casts out baseball’s best punchlines,” USA Today, October 14, 1997.

12 Adam McCalvy, “Brewers celebrate native son Uecker; ‘Mr. Baseball’ honored as Milwaukee’s first home-grown player,” MLB.com, May 12, 2009 (http://mlb.mlb.com/news/article.jspymd=20090512&content_id=4686608&vkey=news_mlb&fext=.jsp&c_id=mlb&partnerId=rss_mlb)

13 Hiestand, “Broadcaster spin years.”

14 Chuck Greenwood, “As Voice of the Brewers, Uecker ‘Just Started Talking,’ ” Sports Collectors Digest, February 5, 1999.

15 Andrew Milner, The St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture, 2000.

16 Uecker, Catcher in the Wry, 31.

17 Richard Sandomir, “World Series, as told by Bob Uecker,” New York Times, October 15, 1995.

18 “A Life of Detours,” Christian Science Monitor.

19 Smith, Voices of Summer, 267.

20 Smith, Voices of Summer, 267.

21 Greenwood, “As Voice of the Brewers.”

22 Peter Carlson, “They Locked Bob Uecker Out of the Bar, but they can’t keep him out of the announcer’s booth,” People, September 18, 1983.

23 Smith, Voices of Summer, 411.

24 Greenwood, “As Voice of the Brewers.”

25 Bob Costas Interview with Bob Uecker, MLB Network, September 28, 2010.

26 Richard Sandomir, “Bob Uecker Returns to the Booth.” New York Times, August 13, 2010.

27 Sandomir, “Bob Uecker Returns to the Booth.”

28 Greenwood, “As Voice of the Brewers.”

29 Dan O’Donnell and Jay Sorgi, “Remembering Merle Harmon,” NBC Milwaukee, May 18, 2009. http://www.todaystmj4.com/news/local/45359962.html

30 Smith, Voices of the Game, 412.

31 “They Locked Bob Uecker Out of the Bar,” People. September 19, 1983.

32 Bob Costas Interview with Bob Uecker, MLB Network, September 28, 2010.

33 Curt Smith, The Storytellers. From Mel Allen to Bob Costas: Sixty Years of Baseball Tales from the Broadcast Booth. (New York: Macmillan, 1995), 267.

34 Shannon Ryan, “Finally, the Front Row: Baseball’s Funnyman Gets a Seat in the Hall,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 23, 2003.

35 Uecker, Catcher in the Wry, 113.

36 Bob Uecker Miller Lite commercial, 1984. (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_Ql7m9LQULM&feature=related)

37 Smith, Voices of Summer, 269.

38 Lauren Simon, “Uecker To Star in new TV sit-com,” USA Today, March 6, 1985.

39 Bob Costas Interview with Bob Uecker, MLB Network, September 28, 2010.

40 Ben Platt. “Popularity of ‘Major League’ remains: Classic Baseball Comedy Celebrates its 20th Anniversary.” MLB.com, April 7, 2009. (http://mlb.mlb.com/news/article_entertainment.jsp?ymd=20090407&content_id=4147526&vkey=entertainment&fext=.jsp)

41 Michael Hunt, “Uecker Heading For Hall,” Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, March 14, 2003.

42 Bob Uecker Ford Frick Award presentation speech, National Baseball Hall of Fame, July 27, 2003.

43 Uecker presentation speech, July 27, 2003.

44 Drew Olson, “Uecker Celebrates Golden Anniversary,” Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, August 27, 2007.

Full Name

Robert George Uecker

Born

January 26, 1934 at Milwaukee, WI (USA)

Died

January 16, 2025 at , ()

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.