Bobby Lowe

Visiting Cincinnati hurler Elton Chamberlain was in Boston’s Congress Street Grounds pitcher’s box for the afternoon game of the May 30, 1894, Decoration Day doubleheader. “Icebox” had no-hit the champ Beaneaters the previous September in Porkopolis (in a game called due to darkness after seven innings) and he was about to face half the same lineup. Leadoff batter Bobby Lowe made the first out, leaving himself 0-for-7 for the day. In the third inning it was 2-2 when Lowe came up again. Baseball history then took a few turns at bat.

Visiting Cincinnati hurler Elton Chamberlain was in Boston’s Congress Street Grounds pitcher’s box for the afternoon game of the May 30, 1894, Decoration Day doubleheader. “Icebox” had no-hit the champ Beaneaters the previous September in Porkopolis (in a game called due to darkness after seven innings) and he was about to face half the same lineup. Leadoff batter Bobby Lowe made the first out, leaving himself 0-for-7 for the day. In the third inning it was 2-2 when Lowe came up again. Baseball history then took a few turns at bat.

Robert Lincoln “Linc” Lowe was born in Pittsburgh on July 10, 1865, just short of three months after the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. His parents were Robert L. Lowe, a railroad and blast-furnace engineer and Jane R. (Crahan) Lowe. In 1868 the family of seven moved 50 miles north to Union Township (also called West New Castle), the next locale west of burgeoning New Castle, an area where furnace-related jobs were numerous. They lived on Bluff Street, just across the Shenango River from New Castle, which gained city status in 1869. On December 6, 1878, tragedy struck the family when a newly repaired blast furnace at the Brier Hill Coal and Mining Co. in Youngstown, Ohio, exploded while being relit. Robert, project boss on the job for two weeks, died the next day from his horrific injuries.1 (This was the same year teammate Billy Nash lost his mother.) To help support his mother and four siblings, teenager Bobby found work as a printer’s devil at the New Castle Courant. There he met compositor Charlie Power, about five years older, who was also an amateur baseball player and team organizer. In the summer of 1881 city doctors and printers planned a friendly community baseball match and Bobby begged for a spot on Power’s team. Appreciating Lowe’s enthusiasm Charlie allowed the youngster to play despite the objections of the older boys. Bobby was the star, impressing everyone who played and watched. As the years passed, Lowe played for a succession of town amateur teams: the James P. Witherow Works (furnace equipment), the Archie Reeds (Reed was a jovial, celebrity railroad conductor), and finally the reborn and more talented Neshannocks (Indian name of largest nearby river), by then (1886) managed by Power. Lowe caught Charlie’s pitches in most games but also was the change hurler.2

New Castle was already on the big-time baseball map because of native sons Joe Quest, an infielder for Chicago and Detroit, and Charlie Bennett, who by the 1880s was the nationally known catcher for the Detroit Wolverines. In 1887 Power and Lowe made their way to Eau Claire, Wisconsin, to play in the Northwestern League. Abe Devine, manager, was skeptical of Lowe’s ability despite Power’s insistence that Bobby was good enough to compete. On May 3 Lowe got his chance to play third base and Power pitched. Bobby homered in a 10-3 loss, scoring twice on three hits. In the following weeks he played some outfield and caught. Starting off 0-11, Eau Claire was destined for last place. Team injuries finally forced Lowe into the daily lineup and he performed beyond expectations. By June 21 manager Devine was fired (team at 7-27) and Quest took over after resigning from his National League umpiring slot. Bobby (.294) became a fixture at third base; Eau Claire finished 39-84. The league disbanded after concluding the season, with the four best teams moving to a better circuit.

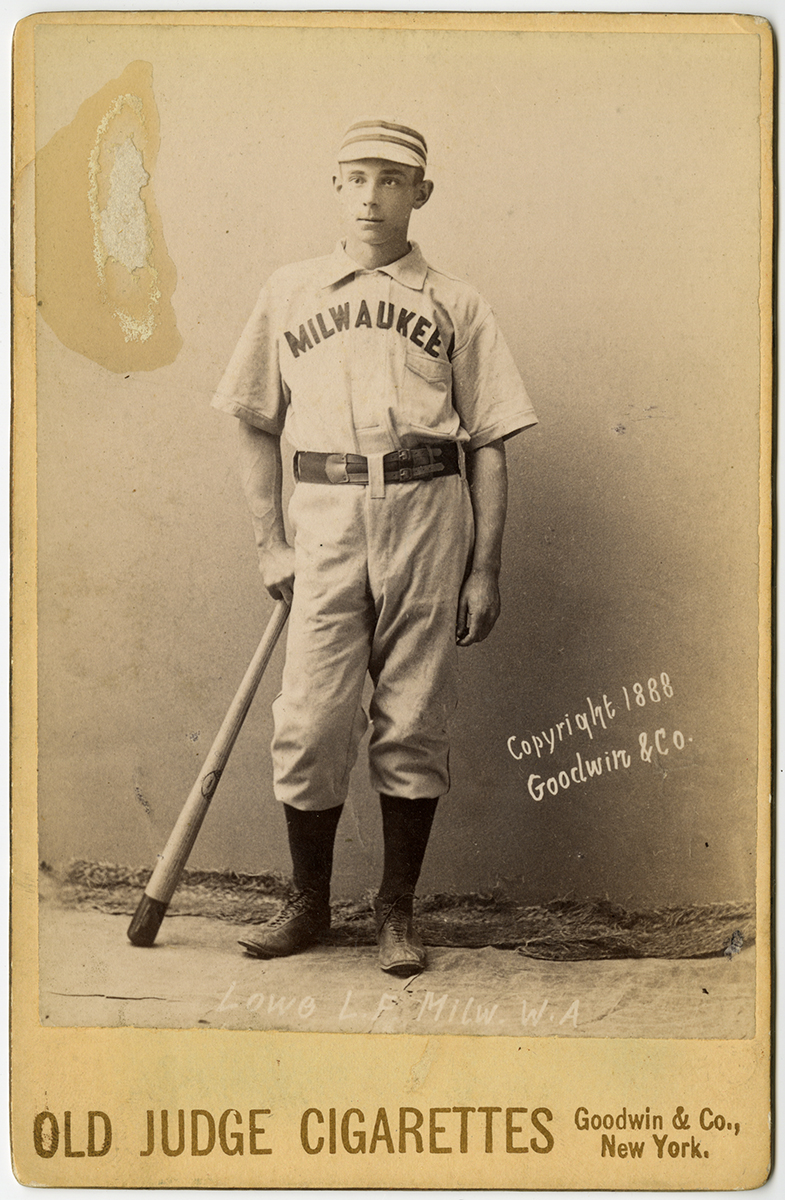

Lowe was picked up by Milwaukee manager James Hart for 1888. The Western Association Brewers were a middle-of-the-pack club and Lowe, playing left field mostly, was batting about .280 when his mom suddenly died in New Castle on July 27. After taking 10 days off for family issues, he was 2-for-25 in his first week back and never really got untracked, hitting .246 by year’s end. While he was in New Castle, Eau Claire was 1-8, scoring just 12 runs. In 1889 the old Boston NL star third baseman Ezra Sutton managed the Milwaukee club as Hart went to Boston to manage its NL entry. Sutton kept Lowe in the outfield but did move him to infield spots when injuries occurred. Ezra’s Creams were marginal, 58-63, ending way behind Frank Selee’s Omaha Omahogs, 83-38, led by pitcher Charlie “Kid” Nichols, 39-8. Lowe finished in the league’s top 10 hitters of those players who appeared in more than half the games, leading his club at .315.

Twisted baseball fate guided Lowe’s next move. Hart left Boston for England in an attempt by baseball’s high powers to ignite some interest across the Atlantic. Boston, with a full roster in 1889, had finished only one game from the pennant claimed by New York despite John Clarkson’s 49 wins. Omaha manager Selee was given the reins of Arthur Soden’s Beaneaters for the chaotic 1890 season when the upstart Brotherhood (Players’) League would be a third major employer along with the NL and the American Association. Underpaid players jumped to higher-bidding teams every day. Signing anyone was a formidable task as contract squabbles and lawsuits prevailed. NL Boston lost seven position players. Taking no chances on the possible fickleness of the PL, Lowe was the first to sign with NL Boston, in October 1889. Selee had seen him in the Western circuit and knew of his ability and character. Since Boston stalwart third baseman Billy Nash had skipped off to the PL Boston Reds, that position was open for Lowe. Another reason for his quick signing was that New Castle hero Charlie Bennett came to Boston in 1889 and now Bobby would get to play with him in the oldest, most stable league. But it all didn’t matter for long, since Bobby got hurt in early May.

Rookie third sacker Lowe was ablaze in his first 10 NL games, leading the NL in hitting (.470) on May 2 when bad knees crippled him. What was thought to be just a short-lived injury to be cured with rest turned into almost no action for three months. Bobby tried to play twice in the outfield, even got hits, but weakness forced him to give up and sit on the bench. A lanky-looking player at 5-feet-10 and 150 pounds, Lowe saw action in only 52 games, managing .280 for the season. It was by far the fewest games the right-handed swinger would play during the 1890s. Boston finished fifth (76-57) behind champ Brooklyn but Selee had cleverly assembled a solid squad for future campaigns.

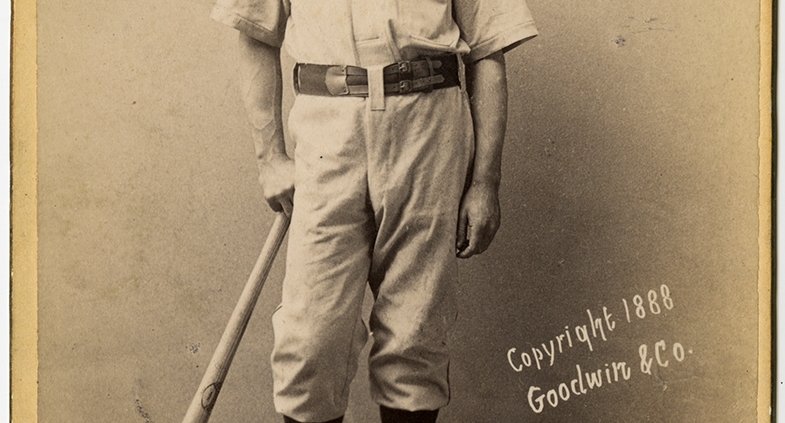

Baseball fans nationwide got their first education about Lowe on January 3, 1891, when the New York Clipper profiled him, explaining his background and route to the Beaneaters.3 The exact same story and image were published by the The Sporting News in its July 25, 1891, issue (front page). When the financially doomed PL folded after one season, popular third baseman Nash was lured back to the South End Grounds and was given the captaincy as part of his “prodigal son” deal. Veteran Joe Quinn was at second so Lowe was relegated to a utility role over the next two seasons. Lowe could play any position well, but his bat soured. He hit .260 and .242, stats that were overlooked as Boston won the pennant both years, including a record 102 victories in 1892 thanks to a longer season. In 1893 the pitcher’s box was moved back from 50 to 60 feet 6 inches and Bobby took advantage, hitting .298 with a team-high 14 home runs (third in the NL behind Phillies slugger Ed Delahanty’s 19). Quinn was dealt to St. Louis for Cliff Carroll and Lowe settled in at second base, a place he’d call home for a decade. Post-1891, the AA also went defunct, and Boston’s outfield had acquired the scoring punch of the Heavenly Twins, Hugh Duffy and Tommy McCarthy, who helped the 1893 squad win a third straight pennant. Nash, Lowe, shortstop phenom Herman Long, and first baseman Tommy Tucker gave the Beaneaters the best all-around infield in the League.

Omen-like tragedy struck the Boston franchise early in 1894. Beloved catcher and Lowe’s hometown buddy Bennett was severely injured in a January railroad accident in Wellsville, Kansas. After speaking to a friend at the depot, he tried to reboard a slowly moving train leaving the station and slipped beneath the wheels. He survived but lost parts of both legs and his career was over. On a brighter personal note, before coming to Boston to start the season, Lowe on April 3 married Harriet “Hattie” Hughes, whose father, Benjamin, and brother Issac ran the Leslie Hotel and a café in New Castle. Almost simultaneously, Duffy was hit with the second tragedy when his wife died while returning from a March trip to visit Southern friends. More bad news awaited.

On May 15, in the 20th game of the season and only the fifth at home, the costliest event occurred when Boston’s South End Grounds, “the architectural crown jewel of nineteenth-century parks,” burned to the ground during a game with Baltimore.4 Starting small under the right-field stands along Berlin Street, the soon unstoppable blaze took 200 Roxbury buildings with it. No one was killed but the Grounds’ ornate witch-hat towers Grand Pavilion was history. The incident forced the Beaneaters to rent the unused PL/AA Congress Street Grounds for their next 27 home games.

Most batters finally caught on to the longer pitching distance in 1894, and the League average spiked to .309, the highest ever. Lowe joined the parade and enjoyed his best season (.346), but he had to settle for second place to the amazing Duffy in Beaneater hits, runs (158, fifth in the league), and home runs. Lowe’s 212 hits placed him fourth in the NL. Duffy whacked 18 home runs (really 19, see the June 20 game account) to Lowe’s 17 to snag that title.

Against the exceptional pitchers of the New York Giants, Rusie (pitching triple crown winner) and Jouett Meekin, runs were at a premium even at short-porched Congress Street, but after that the ballpark’s penchant for big scores took over. Lowe was collared by both Giants and a few days later he was 0-for-6 against Cincy’s Tom Parrott in the morning tilt of the Decoration Day twin bill, taken 13-10 by Boston. He and wife Hattie then had lunch at a North Station restaurant before returning to the Congress Street yard for the afternoon contest against Icebox Chamberlain.

Elton was 2-2 there lifetime and got Bobby out as leadoff batter, but did give up two quick scores. In the third inning Lowe took his first historic swing and smashed a pitch over the left-field fence for a 3-2 lead, then repeated that before the inning concluded. His two home runs in the inning ignited the host Beaneaters to an 11-2 lead. Icebox had melted but was still in the box when, continuing his surreal groove, Lowe blasted his third round-tripper in the fifth, and in the sixth frame he and Keystone pal Long drove back-to-back circuit blasts. The roaring crowd saw Bobby once more that day; he singled in the seventh much to their good-natured dismay. Kid Nichols took the 20-11 victory and Lowe walked away with a single-game record of four home runs and 17 total bases, tied by Delahanty in 1896 but not surpassed until Milwaukee’s Joe Adcock did so in 1954 at Ebbets Field (18 total bases).

In appreciation of the entertaining afternoon power splurge, the jubilant patrons threw about $160 worth of coins on the field for Lowe to pocket. His worst and best games ever had come on the same day. Recounting the feat many times as the years passed, he claimed that all four clouts fell within 30 feet of each other.5

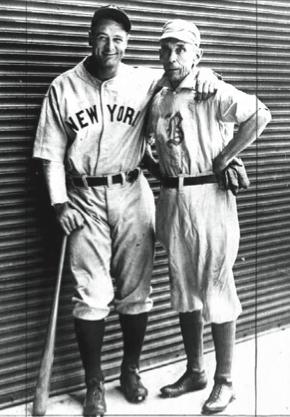

On June 3, 1932, Lou Gehrig matched Bobby Lowe’s feat of four home home runs in a single game, set in 1894.

Ned Hanlon’s Orioles eventually pulled away from the Beaneaters in September (20-3 to 14-11) and took the pennant, preventing a fourth straight Boston title. Selee’s club had beaten Baltimore 8-4 in games but didn’t crush the bad teams as often, finishing eight games behind Baltimore despite hitting .331 and plating the most runs (1,220). Lowe, as leadoff batter most of the season, led the NL with 613 at-bats and was second to Billy Hamilton of Philly in plate appearances. Good health, knees included, allowed Bobby to play all 133 games.

In 1895 the Beaneaters figured to bounce back, but it never happened. They pitched decently but hit .041 less, finishing fifth at 71-60-2. Lowe hit .297 and scored 102 runs, but Baltimore (87-43-2) took its second pennant. The Orioles defeated Boston in 10 of 12 games, the worst season series beating by one team of the decade over Selee’s squad. By midseason Boston had dugout trouble as rumors abounded that cliques had formed. An offseason blockbuster deal sent third-base fixture Nash to Philadelphia to play and manage the 1896 Phillies in exchange for bat wizard and flychaser Hamilton. McCarthy was then sent packing to Brooklyn for his final season. Lowe hit .320 but played in only 73 games due to injuries. Rookie Marty Bergen caught well (.269), phenom Jimmy Collins (.296) handled third base, and Hamilton was terrific (.366, 110 walks, 153 runs), but it was not enough to derail the Orioles express (90-39), which claimed a third straight flag. Rookie switch-hitter Dan McGann (.322) filled in for Lowe at second; it was his only year as a Beaneater.

Slugger Charles “Chick” Stahl (.354) came to Boston in 1897. He was the only major roster change as the Beaneaters tried to dethrone the thrice pennant-winning Orioles. The two rivals nearly matched each other in pitching and hitting and split their 12 games. Selee’s squad did manage to outscore (1,025-964) and outhomer the Orioles. Boston edged Baltimore by two games for the pennant, thanks to the New York Giants beating Baltimore 7 of 12 times, while the Beaneaters whipped New York 8 of 12. Boston’s team average was .319. Making up for catcher Bergen’s .248 was pitcher-outfielder Jack Stivetts (11-4, .367). Lowe batted .309 and knocked home 106 runs while playing excellent defense behind Nichols’ 31-11 record and that of Fred Klobedanz (26-7).

In 1898 Baltimore’s hitting and pitching were a shade better than Boston’s and they even scored more runs, but Boston won 102 games in the expanded schedule of 154 games and edged the Orioles to win the flag for a fifth time in the 1890s, this time by six games. The Beaneaters’ average dropped to .290 despite Hamilton’s topping the club at .369/110 runs. Lowe chipped in a decent .272/94 RBIs and led the club with 20 sacrifices. Bobby’s fielding (.952) was second best in the league.

Ending the fabulous 1890s Gilded decade and the century, Lowe’s average didn’t change much with age, (.272 and .278), 88 and 71 RBIs, as the Beaneaters finished second to Brooklyn in 1899 before sinking to 66-72 in 1900 when their great pitching finally declined. In each of those years, Lowe was still a top-fielding second baseman while playing 279 games. The Beaneaters dynasty was all but over, and in 1902 three of the oldest South End Grounders moved on. Selee went to North Side Chicago to manage the Cubs and Lowe went with him to be a veteran presence. Nichols headed back to the Midwest, leaving Long as the longest-term Beaneater, but even he was gone by 1903.

In Chicago Lowe was made captain and played well (.248), replacing the retired Clarence “Cupid” Childs. Bobby was the fourth infielder when Frank Chance and rookies Joe Tinker and Johnny Evers (debut) took the field together for the first time on September 1, 1902. It was a bit depressing for Lowe to watch his new team hit just six homers all season. A broken kneecap allowed him only 32 games in 1903 (.267). He played mostly second base for Selee’s Cubs in April, May, and half of June, but on the 13th his knees hurt terribly. It was diagnosed as water on the knee, and all thought rest would be helpful. On July 4, after three weeks off, Lowe got his last hit and run for Chicago at the West Side Grounds while making three errors in a 16-9 win over New York. Then doctors’ X-rays discovered the real problem. Regretting the inevitable, Selee released his old soldier on July 18 so he might latch on to another club as a manager.6

Durand Clarence Packard, owner of Denver’s Grizzlies of the Western Association, signed Lowe to pilot the team starting July 28 as manager Ed Barrow had departed. In his first series as manager, Lowe was pitted against old pitching-ace pal Nichols, who was manager-pitcher for Kansas City. In 1904 Lowe tried to catch on with the thrice-NL champ Pirates and spent March in Hot Springs, Arkansas, playing for the Pittsburgh Yanigans. Spring training improved his health and he signed a Pirates contract on April 14, only to be released on the 19th after one at-bat, a pinch-hit strikeout in a 6-5 loss at St. Louis. But Lowe had Tiger friends and he immediately went to Detroit, where a spot at second base awaited. On April 23 he started his first game of 140, and finished second among AL second basemen in fielding (.964) but hit just .208. He was again with New Castle legend Charlie Bennett, who was a Bengals coach.

On July 24 manager Ed Barrow had resigned. Owner William H. Yawkey (uncle of future Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey) and business manager Frank Navin chose Lowe as manager to finish the season. Detroit went 30-44 under Lowe. At age 39 in 1905, Lowe gave up managing and became the Tigers utilityman, playing all infield positions and some outfield in his 58 games (.193). Lowe remained with Detroit for another 58 games in 1906-07, hitting .214. Lowe claimed the major-league players’ “hard luck” title in 1906. First a bout with malaria shelved him, followed by a torn fingernail and a sprained ankle, both topped by a broken nose from his own fouled bunt attempt in drizzly Philadelphia on August 25. That finished his season.7

In 1907 Lowe started the spring as baseball coach at the University of Michigan (11-4-1). He returned to the Tigers for 17 games, appearing only once before August 13. He subbed at third base mostly and pinch-hit twice. All of his final career hits, RBIs, and an error came in the club’s final games on October 6, a doubleheader at St. Louis, as AL champ Detroit rested regulars for the World Series. Lowe knocked in runs in each first inning, first off rookie Bill Bailey and then off veteran Harry Howell, but the Browns won 10-4 and 10-3. Lowe hung around long enough to play with Ty Cobb and see the Tigers take the 1907 AL pennant under manager Hughie Jennings, his old Orioles adversary.

The 1908 baseball season saw Lowe in Grand Rapids, Michigan, managing the Central League’s Wolverines. They finished 68-71 in fifth place behind Evansville. In 1909 he signed with Washington and Jefferson College, southwest of Pittsburgh, to coach that college squad. Off and on he was still there in 1914.

According to the 1910 census, Bobby and Hattie were in Detroit and he was listed as a “baseball traveler” as he scouted for the Tigers for a few years. Their residence then at 617 John R. Road is 300 feet from present-day Comerica Park. About 1922 Lowe found a comfortable position with the Detroit Public Works Department, where he was employed as an inspector of streets and sewers until retirement in the 1940s. Bobby’s entire family – parents Robert and Jane, three sisters, Mary, Lida, and Olive, and brother, Charles, all died before 1900. His wife, Hattie, died in September 1947, and Lowe, suffering from crippling neuritis, passed away in Detroit at the Arnold Home for the Aged/Retired on December 8, 1951, three days after Shoeless Joe Jackson (Greenville, South Carolina). The Lowes are buried in north Detroit’s Evergreen Cemetery, south of Woodlawn Cemetery near Palmer Park.

Lowe’s notable diamond exploits are not limited to his four-homer outburst on May 30, 1894. He had a six-hit game and three five-hit games; in one of them he scored six runs (May 3, 1895, 27-11 versus visiting Washington). Over a five-year span, Lowe clouted four home runs off fellow Pittsburgher Addison Gumbert, equaling his four off the Icebox in four innings. Though his Decoration Day record gets the most attention, Lowe said that his second favorite game was as a Cub on June 22, 1902. In the longest game ever at the West Side Grounds, Chicago beat champ Pittsburgh 3-2 in 19 innings. Lowe helped tie the game in the ninth and won it 10 frames later with an RBI single off stalwart Charles Deacon Phillippe before a howling crowd of 10,000.8 According to a list of home runs specifically hit by second basemen through 1900, compiled by era expert Dave Nemec, Lowe ranks second only to Chicago’s Fred Pfeffer, 93 to 56, with McPhee at 53. Since Pfeffer and McPhee played mainly in the 1880s, by default Bobby Lowe is easily the premier Keystone slugger of the 1890s. Both Pfeffer and Lowe took good advantage of home-field short porches.

In March 1911 his ex-teammate and by then a respected manager, Fred Tenney, wrote in the New York Times that Lowe was the best all-around utility player of his era, able to handle any position smoothly as well as wield a solid bat.9 Lowe’s three grand slams came in successive years, off George Haddock in May 1893, Charlie Petty in May ’94 and Ernie Beam in August ’95. Of Bobby’s 71 home runs, half were with men on base.

Considered a gentleman and exceptional baseball citizen, Lowe was ejected only twice in his career, never as Beaneater. On August 13, 1902, Tom Brown expelled him for arguing a decision, and on July 22, 1904, ump Frank Dwyer didn’t appreciate Lowe and Wild Bill Donovan bringing flaming newspapers on to the field in the 13th inning of a scoreless game in Washington to indicate they felt it was too dark to continue. While going from Hot Springs to Grand Rapids for the start of his 1908 managerial season, Linc and Hattie stopped in Fort Wayne to see the mother of former teammate Chick Stahl, who had committed suicide the year before.

Boston Braves captain and 1914 World Series champ (and future Hall of Famer) Johnny Evers penned the best evidence of Lowe’s grand baseball citizen credentials. In a syndicated column in March 1915, Evers recalled 37-year-old Bobby on the Cubs in 1903 guiding 21-year-old Evers through the baseball wars. “Lowe was one of the best friends I had in baseball during my struggle to stick,” Evers wrote. “He did everything he could for me. Lowe later went into the insurance business and I am glad to say that I took the first policy he ever wrote. He is now scouting for Detroit. Selee had been with him for 12 years in Boston and when it came time to give Bobby his release, Selee wouldn’t do it. The Chicago club finally gave it to the veteran and a grand player passed out of the league. The members of the Cubs bought Lowe a diamond watch fob as a mark of esteem before he hung up his spangles for good. I want to say that I believe Bobby Lowe had more to do with me making good than any other man in baseball, with his kindly advice and valuable tips which he had gathered during his long experience. I was sorry to see him go.”10

Lowe made his final appearance in a Boston uniform on September 11, 1922, at Braves Field. He was one of the Old Timers invited to a benefit game there for Children’s Hospital. Some 20,000 fans saw about 40 stars of bygone days and Bobby was 1-for-1 in the 28-7 loss to the AL team. The Detroit Free Press ran a humorous anecdote in 1948 about Ty Cobb and his wife visiting the Lowes in Detroit in the late 1930s. The wives were in the living room when they heard commotion in the kitchen. Ty had told Bobby he developed a slide technique that enabled him to avoid any tag. Lowe tried to prove him wrong and the two retired teammates were wrestling on the floor before the ladies called a halt to the childish ruckus.11 Bobby had the “guest of honor” head-table spot for the April 1938 Old Timers Association gathering to welcome the new season in the Motor City.

Because of his longevity as a Beaneater, Lowe is in the top 10 of several categories in the descendant Braves franchise history. He is fourth in stolen bases and fifth in hit by pitches, and ranks eighth, ninth or 10th in games, at-bats, runs, RBIs, average, hits, triples, and sacrifices. In the Detroit Free Press, New York sportswriter Whitney Martin composed an unexpected tribute to Lowe for the August 19, 1942, edition. His theme was great second basemen through the years and included elders Nap Lajoie, Bid McPhee, Charlie Gehringer and Rogers Hornsby. The headline read, “Speaking of Great Second Basemen, Don’t Forget Lowe.”12 Bobby never received a single Hall of Fame vote.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Ancestry.com, Baseball-Reference.com, Lowe’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Baseball America’s Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and the following newspapers: Boston Herald, Boston Post, Cincinnati Enquirer, Fort Wayne Daily News, Milwaukee Journal, New Castle (Pennsylvania) News, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, and The Sporting News. Thanks to David Nemec for supplying nineteenth-century home-run statistics.

Photo credits

National Baseball Hall of Fame Library and John Thorn.

Notes

1 “Hot Blast Explosion,” Youngstown (Ohio) Vindicator, December 13, 1878: 5.

2 “Brilliant Player – Story of How Bobby Lowe Was Discovered,” Boston Globe, December 22, 1895: 15.

3 New York Clipper, January 3, 1891: 681.

4 John Pastier, “Constructing Paradise: the Evolution of the Ballpark,” Ballparks Yesterday and Today (Edison, New Jersey: Chartwell Books, Inc., 2007), 13.

5 See Bob Latshaw, “4 Homers in One Game!” Detroit Free Press, March 23, 1947: 31, and “Bobby Lowe Dies at 83,” Boston Globe, December 10, 1951: 10.

6 “Capt. Lowe Is Released,” Chicago Tribune, July 9, 1903: 8.

7 “Bobby Lowe Claims the Hard-Luck Title,” Pittsburgh Press, September 26, 1906: 14.

8 “Four Homers in One Game,” Detroit Free Press, March 23, 1947: 31.

9 Fred Tenney, “Bobby Lowe Best Utility Player,” New York Times, March 14, 1911: 9.

10 Johnny Evers, “Some More Inside History,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, March 3, 1915: 9.

11 Lyall Smith, “As of Today; Even Cobb Had His Moments,” Detroit Free Press, May 9, 1948: C-1.

12 Whitney Martin (Associated Press), “Speaking of Great Second Basemen, Don’t Forget Lowe,” Detroit Free Press, August 19, 1942: 15.

Full Name

Robert Lincoln Lowe

Born

July 10, 1865 at Pittsburgh, PA (USA)

Died

December 8, 1951 at Detroit, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.