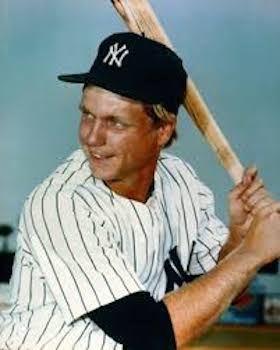

Brian Doyle

Nobody in Hollywood would have tried to produce a script that would end like this,” said New York Yankee manager Bob Lemon after his charges came back from a two-games to none deficit to defeat the Los Angeles Dodgers in the 1978 World Series. Having reached the Fall Classic on the broad shoulders of sluggers Graig Nettles, Chris Chambliss, and future HOF outfielder Reggie Jackson, the club derived its Series inspiration and spunk from its number eight and number nine hitters Brian Doyle and Bucky Dent. “Dent and Doyle?” asked columnist Furman Bisher of The Sporting News. “Reads more like sound effect than people . . . Plink and plunk.” Whatever its sounds, the production from the bottom of their order helped put the Yankees over the top to capture the franchise’s 22nd world championship.1

Nobody in Hollywood would have tried to produce a script that would end like this,” said New York Yankee manager Bob Lemon after his charges came back from a two-games to none deficit to defeat the Los Angeles Dodgers in the 1978 World Series. Having reached the Fall Classic on the broad shoulders of sluggers Graig Nettles, Chris Chambliss, and future HOF outfielder Reggie Jackson, the club derived its Series inspiration and spunk from its number eight and number nine hitters Brian Doyle and Bucky Dent. “Dent and Doyle?” asked columnist Furman Bisher of The Sporting News. “Reads more like sound effect than people . . . Plink and plunk.” Whatever its sounds, the production from the bottom of their order helped put the Yankees over the top to capture the franchise’s 22nd world championship.1

Though Dent won the MVP award, Doyle’s team-best .438 Series average paced the Bronx Bombers. He had not rated a single line in the Series program and was not even made eligible until minutes before Game One after Yankee second baseman Willie Randolph’s injured leg proved unstable. But by Series’ end Doyle would join the ranks of Howard Ehmke, Bill Bevens, and Al Weis as unlikely World Series heroes. “A prime exhibit in the Horatio Alger showcase . . . [Doyle’s] credentials were scarcely the type of which World Series dreams are made.”2

Brian Reed Doyle and his identical twin brother Blake were born on January 26, 1954, the last of four children of Robert Shelby and Virginia Kathryn (Toohey) Doyle, in Glasgow, Kentucky, 95 miles south of Louisville.3 In the 1760s Brian’s four-great grandfather Samuel Doyle (a/k/a Doyel) arrived in Virginia from County Carlow, Ireland, and substantial evidence suggests he served as a militia private during the Revolutionary War. After the war Samuel moved to North Carolina before eventually settling east of Louisville, Kentucky. Around 1800, his eldest sons continued the trek south to Kentucky’s Bowling Green region where Doyle descendants proliferated for generations (the “Doyel” spelling appears to have been discontinued in the late 1800s). In 1917 Brian’s father was born in Barren County about 30 miles east of Bowling Green. An extraordinary athlete, Robert excelled in basketball, tennis, and eventually semi-pro baseball (later joined in this latter pursuit by his eldest son, future major leaguer Denny Doyle). Robert, Sr. turned down a University of Kentucky basketball scholarship in part because his father, a hard-working farmer, strongly discouraged sports. Robert the younger took a different path; after marrying his high school sweetheart in 1940, the couple never missed an athletic event in which their children were involved.

The children attended Caverna High School in Horse Cave, Kentucky. Through 2015 the Caverna Colonels have achieved two state baseball championships. The first came in 1961, under the guidance of Denny Doyle, and the second 11 years later under Brian and Blake (an accomplished pitcher and shortstop). In 1972, during his senior year in high school, Brian, who also starred in basketball and football, received athletic scholarship offers from a variety of Division I schools. However the Doyle home had experienced radical upheaval. Finances nosedived after Robert, a successful building contractor, suffered a heart attack. The large bonuses being offered by every major league club offered Brian an opportunity to assist the family. Both he and Blake made themselves available in the June 1972 amateur draft. In a deep class that included hurler Bob Purkey’s son and HOF manager Walter Alston’s grandson, Brian and Blake were selected in the fourth round by the Texas Rangers and Baltimore Orioles, respectively.

Signed by former major league infielder and longtime scout Hillis Layne, Doyle was assigned to the Geneva (New York) Senators in the Short-Season A New York-Pennsylvania League. The diminutive infielder—5’10”, maybe 160 pounds if he had a large wad of tobacco in his mouth—had an immediate impact launching his professional career with an eight-game hitting streak. In a circuit not known for hitting—league average: .247—Doyle placed among the club leaders with a .256/.390/.363 slash line with 16 stolen bases in 215 at-bats. On August 13 he delivered a 9th inning game winning hit to cap a dramatic come-from-behind win as the Senators scored six runs with two outs to edge the Batavia Trojans 7-6. Doyle also had an impact on the field at shortstop. Drawing comparisons to his older brother as a “master at the double play,”4 Doyle helped his team to a league leading 69 double plays. But like teammate Mike Hargrove, whose between-pitch ritual at the plate earned him the nickname “The Human Rain Delay” in the majors, Doyle had his own amusingly peculiar regimen:

After each offering by his pitcher, Doyle will spit some tobacco juice over his right shoulder, wipe his mouth with his right sleeve, wipe his mouth with his left sleeve, bring his right hand to the front of his cap, bring his right hand to the back of his cap, remove his fielder’s [sic] glove, bring his left hand to the front of his cap, bring his left hand to the back of his cap for one final adjustment and put his fielder’s glove back on his left hand. “It’s just a habit I guess,” Doyle [said.] “I’ve been doing it for as long as I can remember.”5

But Doyle’s first year success soured over the next three seasons. Shifted primarily to second base, in 1974 he endured an injury-plagued year—a mere 115 at-bats—with the Pittsfield (Massachusetts) Rangers in the Eastern League. The next year, following a demotion to the Lynchburg, Virginia, affiliate in the Carolina League (Class A), Doyle struggled with a .183-0-10 line in his last 47 games. But he suddenly bounced back in 1976. Moved to the hot corner with the San Antonio Brewers in the Texas circuit—and excluding two games at first base, Doyle would spend his entire career shifting around the remainder of the infield—he surged to a .349 pace in his first 25 games to earn a rapid promotion to AAA Sacramento in the Pacific Coast League. On August 8, his four hits led the Solons to an 11-1 rout of the Spokane Indians, and he finished with a .290-3-32 line in 393 at-bats. The rebound quickly attracted attention from other major league clubs. On February 17, 1977 he was traded to the Yankees alongside fellow minor league infielder Greg Pryor and $25,000 for veteran utility player Sandy Alomar.

Doyle was assigned to the Syracuse Chiefs in the International League and picked up where he had left off in the PCL (nine hits in his first 26 at-bats). On May 16, 1977, for the first time in his professional career, he played opposite his twin who was manning second base for the Rochester Red Wings.6 (If different jerseys still made it difficult to tell the identical twins apart, Doyle jokingly tried to help: “It’s easy to tell us apart . . . I chew tobacco on the right side, [Blake] chews it on the left.”)7 Four days later Doyle led the Chiefs to a 3-2 win over the Red Wings with a sixth inning homer and an extra-inning walk-off RBI. On June 11, he delivered three hits in a 6-5 extra-inning win over the Charleston Charlies followed shortly by a four-hit performance against the Toledo Mud Hens. Seemingly on pace for a promotion to the majors, Doyle got sidetracked by severely damaged finger in July. Excepting a six-hit bump against Toledo in the final series on September 4-5, he tumbled to a .200-0-19 slump through the second half of the season. His defense suffered as well. “I felt I was in the Twilight Zone,” Doyle said after his late-inning error helped the Pawtucket Red Sox shade the Chiefs in an 11-9 slugfest.8

In spring of 1978, back to full health, Doyle launched a promising (and well-timed) start. Laterally assigned to Tacoma in the PCL, he was called up to the parent club in April after Yankee infielder Mickey Klutts broke his thumb warming up a pitcher in the bullpen. The call initiated Doyle’s season-long odyssey of reassignments and recalls to the big league. Some wag suggested that Yankees’ managers Billy Martin, Dick Howser, and Bob Lemon, severely handicapped by injuries to their players, “had to call for volunteers before making out [the] lineup card.”9 (At the end of the season there similar wags suggested the team doctor be nominated as the Yankees’ MVP.)

Doyle made his major league debut on April 30, in Yankee Stadium against Minnesota. Replacing perennial All Star Willie Randolph at second base, Doyle was flawless in the field but hitless in three at-bats against Twins’ righty Roger Erickson. Fellow Tacoma infielder George Zeber briefly took Doyle’s roster spot, but that move flipped in June after Doyle lashed out at a .333 pace in his first 75 at-bats in the PCL, including a five-hit performance against the Vancouver Canadians on June 5. Twelve days later he garnered his first two major league hits in a 4-0 win against the California Angels. Yet Willie Randolph was not going to be unseated easily. When first baseman Jim Spencer came off the DL in August, Doyle (who had a mere 15 at-bats in July) was returned to Tacoma despite his “Eddie Stanky . . . tough as cement” approach.10 Still Doyle, “a solid fielder and good, all-round utility player,” had made a positive impression on the often crusty New York press.11

Doyle rejoined the Yankees as a September call-up and made just one appearance as a defensive replacement as the club tried to hold on to their narrow first place margin. On September 29 Randolph pulled a hamstring running out an eighth inning infield single. Inserted as a pinch-runner, Doyle scored the winning tally in a 3-1 comeback victory. The injury ended Randolph’s season, and the Yankees finished the few remaining games of the season platooning Doyle and utility infielder Fred Stanley at second base. On October 2 the Yankees defeated the Boston Red Sox in a one game playoff to capture the AL East crown. The next day—a date he normally would have spent travelling to his offseason job selling shirts and fitting customers at Gold & Farley’s clothing store in Bowling Green—Doyle instead found himself in Kansas City starting in Game One of the ALCS. He contributed his first ever career RBI among two hits in a 7-1 opening win against the Royals. Doyle appeared in two of the three remaining playoff games as the Yankees eliminated the Royals and headed for the World Series.

Interestingly, Doyle started against right-handers despite a much better career average in limited play against lefties (Stanley performed better against southpaws as well, but only marginally so). Doyle sat out Game One and the start of Game Four against Los Angeles Dodgers’ lefty Tommy John. He got his first World Series hit in the fourth inning of Game Two as the Yankees lost their second game in Los Angeles. But by October 14, the Bronx Bombers had tied the Series at two games apiece on their home turf. The next day the Dodgers took an early 2-0 lead before nine-hole hitter Bucky Dent’s leadoff walk in the third opened the floodgates. The next inning Doyle—batting eighth—drove a single to center field to continue the onslaught in a lopsided 12-2 win. Doyle and Dent got six of the club’s 12 hits and scored one-third of their runs. They weren’t through. On October 17, back the West coast, the pair collected three hits apiece for the second straight game while collectively driving in five runs and scoring two in a 7-2 win that clinched the Series for the Yankees. Doyle’s RBI double in the second—his first extra-base hit in the majors—tied the game, while his sixth inning RBI single against future HOF inductee Don Sutton provided breathing room for the Yankees’ then one-run lead. After the game Doyle identified his Series heroics as his greatest baseball achievement adding, “[a]ll I know [is] . . . I’m not going to sell clothes this winter.”12 A week later, in a parade worthy of a conquering Caesar, he was honored with “Brian Doyle Day” in Cave City, Kentucky. Doyle spent a busy winter in Florida alongside his brothers establishing the Doyle Baseball instructional school. The concept, which had evolved at least a year before, immediately benefitted from his new-found name recognition. When not working with his brothers Doyle could be found on the rubber-chicken circuit. In January 1979, the Yankees’ twice failed to extract future HOF infielder Rod Carew from the Twins for a large mix of players that included first base slugger Chris Chambliss and Brian Doyle.

With Randolph’s expected healthy return, Doyle had no illusions as to his job on the 1979 Yankees. “I knew what I’d be doing this year, what my role on this team is,” he said. “If you’re going to be a utilityman, there’s no better place to be one than on the best team in the world.”13 Noted for his relentlessly positive outlook, Doyle willingly surrendered his uniform number 25 to free agent signee Tommy John. But in June, as injuries devastated the Yankees’ pitching—they would use an almost league-leading 19 pitchers that season—the club assigned Doyle to the Columbus Clippers in the International League to clear roster space for reliever Ron Davis. Doyle returned in July and again in September but saw little play—32 at-bats in 20 appearances.

The 1980 season echoed 1979. Doyle’s season-long Columbus to New York and back shuffle earned him the dubious Otis Elevator Award. Subbing at varied times for the injured trio of Dent, Stanley, and third baseman Graig Nettles, Doyle earned a career high 13 hits in 75 at-bats including his only major league home run, a solo shot against Cleveland Indians righty Len Barker on June 29. In November, the Yankees traded Doyle to the Oakland Athletics to complete an earlier trade for pitcher Mike Morgan, but Commissioner Bowie Kuhn voided the transfer because Doyle had once again been assigned to Columbus. On December 8, the Athletics made it official by selecting Doyle in the rule 5 draft.

In 1982, the prospect of a regular role dangled before Doyle since the A’s had not had a fulltime second baseman in two years. He started three of the season’s first four games before being sidelined by a hamstring injury. He returned in May and received the bulk of play at second before a May 24 collision with Toronto Blue Jays designated hitter Otto Velez, who was attempting to break up a double play. The crash not only landed Doyle on the 15-day disabled list with a separated shoulder, but it ended his major league career. In June, before he had fully healed, Doyle was assigned to the Tacoma Tigers in the PCL. The next year he shuffled between Toronto and Cleveland affiliates in the International League. On June 26, 1982, playing for the Charleston Charlies, Doyle stole home plate against the Richmond Braves. The next day he cleverly pulled the hidden ball trick against Braves’ outfielder Leo Vargas. But 1982 marked the end of Doyle’s playing career. The next year he managed Cleveland’s Short Season-A Batavia (New York) Trojans in the New York-Pennsylvania League and spent the 1984-85 campaigns as a Cleveland Indians coach under manager Pat Corrales. But these events proved the final hurrah for Doyle. In 1984 he retired from organized baseball and returned to his adopted home of Winter Haven, Florida, to his family of four.

Doyle had married Kentucky-native and childhood sweetheart Connie Payton in Horse Cave, Kentucky, in December 1973. The union produced a son Kirk and a daughter Kristin. Though he continued to maintain his close association with his brothers’ Doyle Baseball school—a camp frequented over the years by such notable guest instructors as Carew, Cal Yastrzemski, Carlton Fisk and Fergie Jenkins—Doyle launched a second career in a higher calling.

In a lengthy interview in 1979 Doyle remarked, “[t]here are more important things in life than baseball. One thing is my Christian faith, which is very important to me.”14 By the 1990s he had put that faith to work. With just a few college semesters under his belt at Western Kentucky University, and no seminary training, Doyle was ordained as a Southern Baptist minister. He received his first placement in 2005 at the Fort Lauderdale First Baptist Church. Serving there until 2011, Doyle and his wife moved to Georgia where he joined the Global Baseball Youth Federation. First placed by Global Baseball in Israel, Doyle went on to develop the federation’s curriculum which took him to Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Ecuador.

In 2011 Doyle and his wife moved to Georgia to be close to their five grandchildren. Three years later he contracted Parkinson’s disease. The debilitating disease slowed but did not fully curtail his active life. In 2016, he awaited the publication of the first of a series of religiously-focused children’s books, and he was working on an autobiography entitled The Call. In 2014, the New York faithful fondly remembered Doyle for his 1978 World Series exploits at an Old Timers Day event at Yankee Stadium.

Noted for “play[ing] defense as if there was a price on his head,” Doyle’s fielding prowess enabled a four year major league career. In 110 major league games, he went to the plate only 199 times. And none too successfully. He managed only a meager .161-1-13 lifetime line that included a singular rarity: a .192 BA, OBP, and SLG in 1978. Doyle lacked “great speed, power or a great arm,” as he himself readily admitted. But in October 1978, in just a few World Series appearances, Doyle captured the attention of the nation.15

Last revised: May 9, 2016

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Rod Nelson, chair of the SABR Scouts Committee, and Tom Schott for review and edit of the narrative.

Sources

Ancestry.com

Brian Doyle, telephone interview, March 29, 2016.

Notes

1 “Dent and Doyle Dynamite Duo,” The Sporting News, November 4, 1978: 24.

2 “Unheralded Doyle, Beattie Preside as Yanks Pour It On,” ibid., October 28: 12.

3 Some sources give his birth year as 1955, but Doyle told the author that 1954 is correct.

4 “Super Glove Work Helps Red Sox Boost Lead,” The Sporting News, August 16, 1975: 11.

5 “Doyle’s Habit,” ibid., August 6, 1977: 34.

6 In 1977 the International League featured a number of familial connections including brothers Lee and Garth Iorg and the sons of HOF inductees Yogi Berra and Whitey Ford.

7 “Martin Casts Vote for Maturing Randolph,” The Sporting News, May 13, 1978: 10.

8 “Doyle in Twilight Zone,” ibid., August 6, 1977: 34.

9 “Yankee Tale—From Turbulence to Triumph,” ibid., October 28, 1978: 20.

10 “Series Star Soon Out of Sight,” ibid., April 7, 1979: 9.

11 “Calendar Takes Big Cut At Yankee Flag Hopes,” ibid., September 9, 1978: 49.

12 “Yanks Do It With Deadly Duo: Dent, Doyle,” ibid., November 4: 41.

13 “Series Star Soon Out of Sight.”

14 “Brian Doyle Just Idle Hero Now,” ibid. May 19, 1979: 14.

15 “Series Star Soon Out of Sight”; “The Imperfect Trifecta or Singles Only, Please,” April 12, 2012. Accessed April 18, 2016, http://bit.ly/1Nudy2u; ibid. (quote).

Full Name

Brian Reed Doyle

Born

January 26, 1954 at Glasgow, KY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.