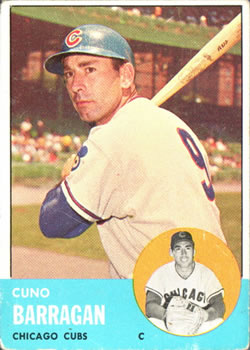

Cuno Barragan

On Friday, September 1, 1961, catcher Facundo “Cuno” Barragan, age 29, made his major-league debut for the lowly Chicago Cubs. He became the 33rd big-leaguer to hit a home run in his first at-bat. In 2017, he recalled, “When I hit it, I was running like it was going to be a double, and then when I saw the umpire signaling a home run, I started laughing.”1 That list has more than tripled in size since then, but is still pretty exclusive company.

On Friday, September 1, 1961, catcher Facundo “Cuno” Barragan, age 29, made his major-league debut for the lowly Chicago Cubs. He became the 33rd big-leaguer to hit a home run in his first at-bat. In 2017, he recalled, “When I hit it, I was running like it was going to be a double, and then when I saw the umpire signaling a home run, I started laughing.”1 That list has more than tripled in size since then, but is still pretty exclusive company.

Unfortunately, that was the only homer that Barragan hit in his short time in the majors: 69 games across three seasons. His pro career ended after 1963.

The series of events that brought Facundo Barragan to Chicago had many twists, turns, challenges, and setbacks. It is hard to imagine a more improbable path than the one that led Barragan to wear a Cubs jersey – maybe even more improbable than the idea Cubs owner Phil Wrigley hatched earlier in 1961, the system of rotating managers called “The College of Coaches.”

Facundo Antonio Barragan was born in Sacramento, California on June 20, 1932. His parents were both immigrants born in Mexico. In Spanish, the accent falls on the last syllable of the family name – Barragán – but he uses the English pronunciation (accent on the first syllable) unless he is speaking Spanish.

Facundo was the youngest of seven children. His father, Claudio, worked at the Southern Pacific Railroad shop in Sacramento, but contracted a disease and died when Cuno was only two years old. The family was on relief, but got by with the children pitching in, earning money wherever they could, and by renting out an upstairs room. His mother, Josefa, did not speak English; everyone spoke Spanish at home. She died at the age of 56 when Cuno was only 15 years old.

For much of his youth, therefore, he was raised by his older siblings: Josephine, Vincent, Caroline, Claude, Guadalupe, and half-brother Joe Alejo. He was closest to brother Claude, who found time to play catch with Cuno and who also played a little semi-pro baseball in Sacramento as a pitcher. Josephine was an outstanding athlete too, playing basketball and softball.

They lived in a multiracial neighborhood on Q Street in downtown Sacramento. Besides school, Cuno spent his days playing sports in the neighborhood. The local kids played baseball in the street, with a broken curb acting as first base, a palm tree as third base, and whatever they could find to put in the street as second base. He also helped the family finances by delivering the Sacramento Bee newspaper, a job that was handed down from brother to brother. During the baseball season he and his buddies would go to Edmonds Field, which was only a few blocks away, and try to get hired to pick up bottles in the stadium after the Sacramento Solons games. Every little bit of income helped the family.

Barragan also has fond memories of the different strategies that he and his friends used to sneak into Solons games. Did he ever think that he would be playing professionally on that field? “No, no, no thought at all. I never had any aspiration to be a professional baseball player. It was just a game to be played at school and in the park,” claims Barragan.2

As a youngster Barragan had a pretty strong arm and envisioned himself as a pitcher. Although Little League did not exist back then, Sacramento had many divisions in the Municipal Summer League. At the age of 11 or 12, Cuno organized his own team in the 100-pound division and got a sponsor. His plan to be the star pitcher quickly evaporated when no one was willing to be catcher. Without a catcher they could not play, so he capitulated and took the spot, wearing borrowed gear. That became his position for the rest of his baseball playing days, both professionally and in the amateur ranks.

Barragan played on his junior high’s baseball team, but was so far down on the depth chart that in the team picture he was not wearing a uniform. From 1947 to 1949 he attended Sacramento High School, where he played football and baseball. Despite not being large, he was tough – enough to be a lineman on the football team. In baseball he played his typical position, catcher. During the football season he also played baseball in the Sacramento Winter Baseball League, starting in the 1949-50 season (he had graduated from high school in midyear).

After high school Barragan attended Sacramento Junior College. Academics did not have much allure for him; after a baseball season in which he was the fourth-string catcher, he quit school and went to work for the Fischer Tile & Marble Company. Figuring that this business was going to be his life’s career path, the young man quickly learned how to set tile.

That path took a major turn when St. Mary’s College in Moraga (in Contra Costa County, near Oakland) dropped its football program. As a result, two of his high school buddies, who were on scholarship to play football at St. Mary’s, left Moraga and came back to play for Sacramento Junior College in 1951. They convinced Barragan to join them. Reticent at first because he was making $75 per week setting tile and had a 1939 Chevy that required upkeep, he finally relented.

He was a first-string linebacker for the Panthers and team MVP, and when baseball season rolled around, he decided to give it another try. While he was not in school, he had continued playing baseball in the County League. Now with more confidence and baseball maturity, he was one of the top players on the team that made it all the way to the state championship, only to lose to Santa Rosa. He led the team in hitting with a .408 average.3

During that summer of 1952, with renewed interest and excitement in baseball, he took part in two semi-pro summer leagues. He played in the County League for the Rio Vista Red Sox and traveled up to Willows to catch for the Glenn County Cardinals in the Sacramento Valley League.

Based on his performance at college and in the summer leagues, the 5’11”, 180-pound catcher was starting to draw interest from baseball scouts, so he decided not to play football. During the tail end of the 1952 Pacific Coast League season he was invited to go to San Francisco for a tryout in which he caught batting practice for the Seals. They offered him a contract to play for the Yakima Bears for the following season. He was not yet 21 years old, so he was unable to sign on the spot without a guardian’s signature.

When Barragan got back to Sacramento, Charlie Graham, Jr., owner of the Solons, caught wind of the trip and contract offer, and immediately made an offer of his own. The lure of playing in his hometown led Barragan to sign with Sacramento. With both parents deceased, his brother Vince had to go down to the courthouse and pay $50 to become Cuno’s legal guardian in order to co-sign the contract. Meanwhile, Harry Fischer, owner of the tile company, tried to convince Barragan that there was no future in a baseball career and that he should come back to a solid career in his business. Although it was not a year-round salary, Barragan believed that being able to play baseball and earn $800 a month during baseball season beat $75 per week setting tile. On February 1, 1953 he married Marlene Spencer, who supported his decision.

So in the spring of 1953, after one of his most active seasons (17 games) in the Sacramento Winter League’s top division, Barragan joined the Solons for spring training in Santa Cruz. Before the regular season began he was optioned to the Idaho Falls Russets, a team in the Class C Pioneer League that had a working agreement with the Solons. They were training in Lodi, California, so off went Cuno to Lodi. He spent the entire season with the Russets. Along with four or five other Sacramento natives, he played well and survived the long bus rides to such places as Salt Lake City, Utah and Great Falls, Montana.

But a roadblock to his baseball career was just around the corner. Barragan remembers, “A lot of my friends were being drafted, so a couple of us went down and enlisted in the Naval Reserve.”4 Among other activities, this required his attendance at weekly meetings. Although he transferred from the 12th Naval District to the 13th, he found that the long bus rides and away games made it difficult to attend the meetings. “At the end of the season when I got home there was a letter from the President of the United States directing me to report to Ford Ord (in California),” Barragan remembers. “Apparently I had missed too many meetings.”5

On the day before he was to report to Ford Ord, he was transferred to the San Diego Naval Training Center to begin his two-year hitch in the service. So he left for San Diego, leaving behind Marlene and their young son, Michael.

Barragan recalls, “I went through the regular training for ten weeks, or whatever it was, and when they were assigning duty onto the aircraft carriers, somebody looked at my billet and saw that I was owned by the Sacramento Solons. The commander in charge decided to keep me there.”6 He spent 1954 in San Diego, working in the post office, but mostly playing baseball for the base team. The next year he was transferred to the Naval Station in Alameda, California, which was a little closer to home. In the service he played third base and also did some pitching.

In the spring of 1956 he was out of the service and went to spring training with the Solons. Again he was optioned out, this time to the Amarillo Gold Sox of the Western League. Playing in a ballpark that often had gusting winds, Cuno used the conditions to his advantage and hit a career-high 10 home runs. He hit .257, but again had to endure long bus rides, including a 28-hour trip from Amarillo to Sioux City, Iowa.

During the off-season Barragan went back to school at Sacramento State College. He also worked as a janitor for the Sacramento Unified School District to help support his family, now with a second son, Stephen. In addition, he appeared in 15 National Division games in the Sacramento Winter League.

In 1957 he finally stuck with the Solons for the entire season, playing in 108 games, but hitting only .193. Following the season he went down to Mexico to play in the Veracruz League for Pericos de Puebla. Although Sacramento had its own Winter League, with some very good players, Barragan figured that playing down in Mexico would improve his game, and he would get paid at the same time. He didn’t stay long, though, because a foul tip broke a finger.7

When spring training 1958 closed, the Solons wanted to ship Barragan out to the Atlanta Crackers, of the Southern Association, to work on his hitting. Feeling that he had paid his dues by catching 108 games the previous season, he did not want to leave his family and refused to go. So he was suspended and went back to work setting tile.

In early July, injuries had left the Portland Beavers with only one catcher. Portland manager Tommy Heath, who was familiar with Barragan after managing the Solons in 1957, inquired about him and was told that he was on the suspended list. So Sacramento made Barragan eligible and sold him, conditionally, to Portland. In order for a player to change teams, money had to change hands, so Portland bought Barragan’s rights for one dollar. He played six games for Portland, batting .250, and then was returned to Sacramento – for $1.

One advantage of his short stint in Portland was a slight change in his contract. Barragan’s contract with Sacramento had called for him to receive 10% of the selling price if he were to be sold to a major league club. Grateful that Barragan had helped fill in for his regulars, the Portland general manager changed it to 25%. That change would pay off in 1960.

With the Solons under new management, Barragan was back with Sacramento to start the 1959 season. In spring training, he outhit the other two catchers on the roster, Clay Dalrymple and Bob Roselli, with a .351 average. In the early part of June, however, his average was only .200. Spokane was in dire need of a catcher, so he was sold to the Indians, again for $1. He finished out the season with Spokane and ended up with a combined .205 average in 195 at-bats. When Sacramento came in fourth place, he was allotted a half-share of the team’s prize money, which amounted to only $28.71.

In 1960, after being sold by Spokane back to the Solons (again for a dollar), Barragan had a strong season – his springboard to the major leagues. Though a wrist injury limited him to 80 games, he batted .318 and had 46 assists. A feature in The Sporting News that August said, “He’s hard as nails, has an abundance of hustle. His catching has improved along with his batting. His arm is both good and accurate. He has developed into a smart handler of pitchers. And, unlike most catchers, Cuno can run.”8 Barragan also said, “My main problem as a hitter was that I tried to pull everything. In 1960, I started to hit the other way, which helped my average.”9

In November 1960, the 28-year-old Barragan was drafted by the Chicago Cubs. The selling price for his services had increased to $25,000, which the Solons pocketed, minus Cuno’s $6,250 cut, thanks to his modified contract. He and his wife also welcomed a third son, David, in November.

In February Barragan signed a contract and set his sights on the Cubs catching job. It wasn’t going to be easy – the Cubs had seven catchers in spring training camp in Mesa, Arizona. He was getting a lot of playing time in the preseason games until March 25, when he broke his ankle while sliding into third base against the Cleveland Indians. Barragan sadly remembers, “I hit a double. On the next play I was being sacrificed to third and I anticipated a play at third base. I was already into my slide when I saw the sign to stand up.”10

Barragan had already become a popular man on the club. After the injury, one of the Cubs coaches, Harry Craft, said, “Nobody likes to see anybody get hurt, but it seems even worse because it happened to Cuno. He was working so hard and was such a likable fellow. You had to admire him for the way he went about his business. I know you’re not supposed to let personal feelings enter into baseball, but I know that deep down a lot of us were hoping that he’d make the club.”11

After getting out of the hospital, Barragan went home to Sacramento to recuperate. After about two months he returned to Chicago to have the cast removed and join the team. He was still a couple of months away from being able to return to the field, so he was handed a 10-power scope and shown the way inside the scoreboard to be the “scoreboard spy.” His job was to steal the catcher’s signals and relay to the batter what type of pitch was coming via a red light switch. Barragan had a funny anecdote about Giants scout Hank Sauer, who was aware of the practice from his years as a Cub in the ’50s. “I always barricaded myself up there, so that no one could come up and catch me stealing signs. So, Sauer came up the ladder and tried that door, but he could not get in, so he started yelling. ‘I know you’re up there Barragan, you SOB! I’m gonna come up there and rip you apart!’”12

When rosters expanded on September 1, Barragan finally got into his first official major league game. Lights at Wrigley Field were still decades away, so all Cubs home games were played during the day. This was a warm and sunny afternoon, with the temperature hitting 90 degrees at the start of the contest. The National League then had just eight teams, and the Cubs were in seventh place, 22 1/2 games behind the first-place Cincinnati Reds. Only the Philadelphia Phillies, deep in the cellar, were worse. It is no wonder that only 5,427 fans were on hand at Wrigley that day. The opponent that day was the San Francisco Giants, who were in fourth place, seven games back.

Barragan got the start for Chicago as the batterymate for right-hander Glen Hobbie. He batted eighth in the order. On the mound for the Giants was a tall lefty, rookie Dick LeMay. After an inning and a half there was no score, but the Cubs got on the board in the bottom of the second inning as Andre Rodgers hit a two-run homer with two outs. Barragan then came to the plate for the first time in the majors. “I don’t remember the excitement of going to bat the first time ’cause there was a home run hit right before me,” says Cuno.13 He belted a LeMay pitch over the left field fence.14

Barragan finished the season playing in only nine more games, though he started eight of those. He batted .214, but did not make an error in 39 chances.

His other most memorable moment that season came in Los Angeles on September 20. It was the last game that the Dodgers played in the Los Angeles Coliseum, since Dodger Stadium (known then as Chavez Ravine) would open the next season. The Dodgers won 3-2 in 13 innings behind a complete-game performance by future Hall of Famer Sandy Koufax, who threw 205 pitches to notch his 18th win of the season.

Barragan started the game for the Cubs. Up to the seventh inning he had struck out twice against Koufax, who ended up with 15 Ks for the game. In the seventh, Koufax threw him two fastballs for strikes; Cuno knew he was overmatched. For some reason Koufax then tossed him a curveball and Barragan met it squarely for a single. In the ninth, he drew a two-out walk. Although he had pretty good speed for a catcher, even after his broken ankle, the Cubs decided to replace him with a pinch runner. There was no embarrassment for him in that the runner was another future Hall of Famer, premier base stealer Lou Brock.

In 1962 Barragan was one of five catchers on the Cubs roster, with at least three being active at all times. Even 35-year-old player/coach El Tappe got behind the plate for 26 games. With a .302 batting average, Dick Bertell got the most action behind the plate, 76 games. Barragan batted .201 in 58 games; Moe Thacker got into 65 games and hit .187; and Sammy Taylor caught only six games, hitting .133.

Without a consistent lineup and having three different managers during the season, it was not surprising that the Cubs ended up in ninth place (out of ten teams), losing 103 games. The only team that was worse was one of the two new expansion clubs, the New York Mets. Even the other new franchise, the Houston Colt .45s, finished ahead of Chicago.

On Opening Day, Barragan got the start against the Colts at Colt Stadium in Houston’s first ever major league game. The Cubs were crushed, 11-2, but Barragan got one hit in three tries. That was his only hit over his next ten games and his average dipped to .063. With an abundance of catchers, he was relegated to the bench for the next 11 days. In the meantime El Tappe had been replaced by Lou Klein as manager.

When Barragan got back into the lineup, the hits started to fall. Against the Phillies and Mets in a stretch of six games, he went 10 for 23 and raised his average to .282. His hitting eventually cooled off and his playing time was sporadic. He did, however, catch the last game of the season, in which the Cubs beat the Mets, 5-1, giving New York a record-setting 120 losses for the season.

On the strength of his hitting in 1962, Dick Bertell was pegged as the Cubs’ starting catcher for the 1963 campaign. The team had a new manager, Bob Kennedy (the College of Coaches had been abandoned), and a couple of new catchers, Merritt Ranew and Jimmie Schaffer. There wasn’t room for the 31-year old Barragan. He got into only one game – his last in the majors – on April 21, striking out in his only at-bat.

Chicago then optioned Barragan to Salt Lake City of the Pacific Coast League. He played in 85 games for the Bees and had the second highest batting average of his career at .284.

Barragan did, however, wear the Cubs uniform one more time. On October 12, 1963, in the last baseball game ever to be played at the Polo Grounds in New York, he was the National League catcher in the one and only Latin American major league players’ game. The exhibition game was a charity benefit. Barragan’s presence shows how much less common Latino players were then – during the 1963 season, not one man born in Latin America played catcher in the NL.15 He caught the whole game and although he went 0 for 3, his squad, which included such stars as Roberto Clemente, Orlando Cepeda, and Juan Marichal, defeated the American League squad, 5-2.

In December 1963, the Cubs traded Barragan to the Los Angeles Dodgers along with pitcher Jim Brewer for pitcher Dick Scott. Despite being invited to the Dodgers’ spring training camp in Vero Beach, Cuno was offered a Triple-A contract, which would have brought him back to Spokane. “They said come to spring training and be a Dodger.” Barragan related. “I said I’m not going without a major league contract.”16 The starting catcher for Los Angeles was Johnny Roseboro, so the most Barragan could have hoped for was a backup position. Without a major league contract he figured that he wouldn’t get a fair look.

Thus, he decided to retire. The Dodgers put him on the suspended list. “They didn’t give me my outright release until I had been in the insurance business for three or four years.”17 There were some good breaks and some bad breaks along Facundo Barragan’s path in baseball. Yet he was grateful for the opportunity to play pro ball for nine years, with and against some of the all-time greats of the game.

Going to school during the off-seasons, Barragan had graduated from Sacramento State College with a degree in Physical Education in 1960. His plan was to go into teaching and coaching once his baseball career was over. A friend in the insurance business, however, convinced him that he could make more money selling insurance than teaching and even more than he could playing baseball. So Barragan left baseball and teaching behind and went to work for Cal Western Life Insurance. He later became an independent agent and remained in the insurance business until his retirement in 2011.

For a few years in the mid-1960s Barragan continued to play semi-pro ball as a player/manager in the Sacramento County League for the team sponsored by Rainbo Bread. As late as 1969, he appeared in a Sacramento Winter League National Division game. He also spent 13 seasons in the Sierras on the ski patrol.

In Sacramento, Barragan is a member of three Halls of Fame. In 1973, he was selected by the Mexican-American Sports Association Hall of Fame; in 2002, he became a member of the LaSalle Club Baseball Hall of Fame and the Sacramento City College Athletic Hall of Fame.

Cuno Barragan lived in the Sacramento suburb of Carmichael with his wife, Karla (née Goff), whom he married on April 14, 2003.18 During the Cubs’ road to the World Series championship in 2016, he became a media star in his hometown area. As a member of the franchise’s “fraternity of futility,” the local networks and newspapers wanted to get his perspective on the team’s run for the crown. He watched the final game in his home, surrounded by a houseful of media personnel. After the Cubbies won, his doorbell rang and it was a neighbor with a round cake, decorated as a baseball with a big blue “W” in the middle.

He died at the age of 91 on May 12, 2024.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Rory Costello for reviewing this biography and contributing some material, including insights on the Latin American players’ game of 1963.

Sources

Interviews

Notes from Ed Carroll’s February 2007 interview with Cuno Barragan

The author’s many conversations with Cuno Barragan from 2013 to 2017, particularly ones on February 28, 2017 and March 14, 2017.

Newspapers

Sacramento Bee and Sacramento Union (Tom Crisp’s research into the archives of these newspapers provided the information on Barragan’s records in the Sacramento Winter League)

Chicago Tribune

Websites

Ancestry.com

Thisgreatgame.com

Books

Alan O’Connor, Gold on the Diamond, Sacramento, California: Big Tomato Press, 2008

Joe Taxeira, A Unique Look at Big League Baseball – Unique History, Photos, & Statistics through 2010, Roswell, Georgia:, Colorwise Commercial Printing, 2011

Notes

1 Tom Crisp, conversation with Cuno Barragan, February 28, 2017.

2 Ibid.

3 Tom Crisp, conversation with Cuno Barragan, March 14, 2017.

4 Crisp conversation with Barragan, February 28, 2017.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Richard A. Santillán, Mexican American Baseball in the Central Coast, Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2013: 81.

8 Wilbur Adams, “Late-Blooming Barragan Hits His Stride at 28,” The Sporting News, August 24, 1960, 29.

9 Ed Attanasio, “They Were There: Cuno Barragan,” This Great Game website (http://www.thisgreatgame.com/cuno-barragan.html)

10 Tom Crisp, conversation with Cuno Barragan, February 28, 2017

11 Jerry Holtzman, “Ankle Break Shelves Top Rookie Barragan,” The Sporting News, April 5, 1961, 24.

12 Attanasio, “They Were There: Cuno Barragan.”

13 Tom Crisp, conversation with Cuno Barragan, February 28, 2017

14 Barragan told Ed Attanasio that it was the first pitch, but in a recent conversation with Tom Crisp, he thought it might have been the second pitch. Available contemporary accounts of the game do not specify.

15 The closest other thing to a Latino catcher in the NL in 1963 was Elmo Plaskett, who was born in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Plaskett caught in five games for the Pittsburgh Pirates that year, He was not on hand that day, though; the other catcher on the NL roster was Italian-American Joe Pignatano.

16 Tom Crisp, conversation with Cuno Barragan, February 28, 2017

17 Ibid.

18 Barragan’s marriage to Marlene ended in divorce in 1966. He was also married a second time from 1983 to 1993.

Full Name

Facundo Anthony Barragan

Born

June 20, 1932 at Sacramento, CA (USA)

Died

May 12, 2024 at Lincoln, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.