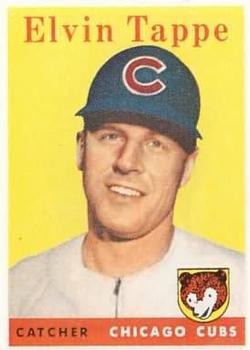

El Tappe

Never known for his hitting ability, catcher El Tappe played 145 games of major-league baseball over parts of six seasons with the Chicago Cubs. In addition, his suggestion in December 1960 to use a rotating system of instructors turned into owner Philip Wrigley’s decision to employ the College of Coaches in 1961 and 1962. Tappe was part of that corps, but in all, he worked 28 years for the Cubs as a player, major-league coach, minor-league manager, and scout.

Never known for his hitting ability, catcher El Tappe played 145 games of major-league baseball over parts of six seasons with the Chicago Cubs. In addition, his suggestion in December 1960 to use a rotating system of instructors turned into owner Philip Wrigley’s decision to employ the College of Coaches in 1961 and 1962. Tappe was part of that corps, but in all, he worked 28 years for the Cubs as a player, major-league coach, minor-league manager, and scout.

A lifetime .207 hitter at the top level, Tappe was well aware of his limitations with the bat. “I probably wouldn’t have made it to the majors if I hadn’t been an outstanding defensive catcher, because I never hit worth a darn,” he said in 1996. “It [catcher] used to be a defensive position and if you got a catcher who also could hit, that was great … They put guys back there now who don’t really catch that well, but hit real well.”1

Elvin Walter Tappe was born on May 21, 1927, in Quincy, Illinois, a city of about 45,000 along the Mississippi River in west central Illinois. The family, of German descent, had been in Quincy for at least two generations prior.2 His parents, Walter Emil Tappe and Marie Sophia “Mamie” Bronestine Tappe, had two other children: a daughter, Winona, born in 1920, and Elvin’s twin brother, Melvin. Mel Tappe pitched nine seasons (1947-55) in the minors, briefly getting as high as Class AA in 1952.

Walter Tappe died in 1972 in Quincy. His World War I draft registration showed his occupation as finisher in wood working. He later worked for the Quincy Board of Education for several years before retiring around 1958. Mamie Tappe died three weeks before her husband in Quincy after suffering a stroke.

Tappe started playing baseball at age 5 or 6 and followed the Cubs from an early age. (Chicago and Quincy are 312 miles apart.) Later, he played for the American Legion Junior baseball team in Quincy and caught for the Louis E. Davis American Legion Post baseball team in Bloomington, Illinois, 153 miles from Quincy.

Tappe was a starting guard on the Quincy High School basketball team that finished third in the Illinois state tournament in 1945 after losing to Champaign and beating Moline. “El was the better shooting guard of the two boys,” teammate Don Bickhaus said in 1998. “The Tappe boys were both super nice, real leaders in all affairs. El was student council president and he was so active that he practically ran the school.”3

Tappe also encouraged the Quincy School District superintendent to form a high school baseball team. “I was president of the student council and Mel was vice president,” Tappe recalled 47 years later. “We went and talked to the superintendent of schools.”4 When the discussion ended, Quincy High School had a baseball team, which finished third in the state in the spring of 1945. As the season developed, El and Mel were considered one of the best teenage catcher-pitcher duos in Illinois.

Tappe also was a twirler in the high school band, a member of the National Honor Society, represented Quincy High School at Rotary Club meetings, and sang in the school chorus. “The Tappe twins have excellent singing voices and have been in demand as entertainers since they were in grade school,” the Chicago Tribune reported.5

After graduating from high school in 1945, Tappe played for the Mare Island Marines baseball team during his 16-month stint in the Navy. Upon his discharge from the Navy, Tappe enrolled at Quincy College, where he played one season of baseball and four seasons of basketball. Four years later, he received a Bachelor of Science degree from the college.

Tappe (and his brother) signed with the unaffiliated Henderson Oilers in the Class C Lone Star League on July 22, 1947. Two days later, El doubled in his professional debut in the Oilers’ 12-6 loss to Tyler. In 27 games that season, the 20-year-old catcher hit .243 (26-for-107). The Oilers finished in seventh place, 12½ games behind the first-place Kilgore Drillers.

In 1948, the Tappe twins were one of four sets of brothers in Texas’s five professional baseball leagues.6 That May 29, 1948, however, Elvin Tappe severely fractured his right ankle while sliding home. It brought his second pro season to an early end; he had hit .283 in 30 games. Henderson finished in fourth place under four managers.

On December 28, 1948, Tappe married Donna Kae Hull, a Quincy High School graduate and National Honor Society member, at Trinity United Church of Christ in Quincy. The couple met in 1946 at a dance after a football game when Tappe was a freshman at Quincy College and Donna was a sophomore at Quincy High.7 The Tappes had a son, Steven, born on April 6, 1951, in Quincy; another son, Stanley, born in September 1953; and a daughter, Tammy, born in 1955.

During his stints as Cubs “head coach,” Tappe was ejected from games twice. On May 29, 1949, he was tossed for the first time in his professional career, by home plate umpire Buck Krauss in the fifth inning for disputing Glenn Burns’s three-run home run just inside the left-field foul pole. Nevertheless, Henderson beat Longview, 8-7, in the second game of a doubleheader at Legion Field at Longview.8 Two days later, Tappe had a game-winning single in the Oilers’ 7-6 win over eventual East Texas League playoff champion Gladewater. He represented the South team in the league’s annual all-star game at Marshall, Texas, on July 11. Tappe finished with his best season yet, hitting .271 with 20 doubles.

Joining the New York Yankees organization in 1950, Tappe was promoted all the way to Class AA but saw limited duty. That August, a Shreveport, Louisiana, sportswriter said, “Tappe’s single claim to distinction is that of having worn out more pairs of pants of sliding up and down the bench than any other player in Texas League history.”9 As the No. 2 catcher behind Clint Courtney in 1950, Tappe played in only 35 games and hit .286 for the Beaumont Roughnecks, the Yankees’ affiliate in the Texas League. On May 5, however, he threw out four of five would-be base stealers in a loss to Fort Worth at Beaumont.

With Courtney’s promotion to Triple-A in 1951, Tappe became Beaumont’s primary catcher. That June 25, 1951, he was hit in the head by Fort Worth hurler Bill Glane and carried off the field on a stretcher. St. Joseph’s Hospital in Fort Worth reported the next day, however, that Tappe was not seriously hurt.10 El hit .244 in 88 games for the fourth-place Roughnecks, who were managed that season by Harry Craft – another future member of the College of Coaches.

On December 3, 1951, Tappe found his long-term employer as the Cubs took him in the minor-league draft.11 He was assigned to Los Angeles in the Pacific Coast League.

Tappe hit .211 for 49 games for Los Angeles in 1952, playing behind first-string catcher Les Peden in 1952, Again, however, he stood out on defense. Tappe “was the best receiver of the two … he (Tappe) could catch any kind of a pitch and field like a fiend on bunts and dribblers.” That view came from L.A. sportswriter Braven Dyer, best remembered today for being punched out in 1964 by Bo Belinsky. Tappe’s hometown paper, the Quincy Herald-Whig, ran it in April 1953.12

Dyer’s account continued, “Rarely have I seen a minor league player with as much hustle as energetic Elvin. He has more pepper than a king-sized enchilada.”13 Les Peden, who’d been obtained by the Washington Senators, got his only shot at the majors to start the 1953 season. Thus, Tappe became the primary catcher for Los Angeles, and his batting perked up. He drove in three runs in the Angels’ opener and hit .281 in 38 games while handling 161 chances without an error.

A couple of months into the season, however, Peden returned to Los Angeles. Tappe was sent to the Des Moines Bruins in the Class A Western League. There he hit .214 in 85 games and was one of four Bruins on the East team in the Western League all-star game.14

Bouncing back from the demotion, Tappe opened the 1954 season with the Cubs. In camp that March, manager Phil Cavarretta said he didn’t expect Tappe to hit much but called him definitely ready defensively,15 The 26-year-old made his major-league debut on April 24 in a 6-5 loss to the Cincinnati Redlegs.16 Cavarretta’s assessment proved accurate: Tappe hit only .185 in 46 games for the Cubs and .188 in 23 games for Des Moines that season. As a January 1955 review noted, he “was rated as a slick receiver, but was weak at the plate.”17

Over that winter, Tappe had his own TV sports show in his hometown of Quincy.18 In the spring of 1955, he received instruction from Cubs teammate Frank Baumholtz, who’d hit .325 three years earlier. “The Cubs know I won’t ever be a power boy,” said Tappe, “and they want me to develop into a spray hitter, aiming down the middle and letting the ball land where it may,” he said.19 He was unable to get a firm grip on the bat after suffering a fractured right hand in high school that didn’t heal properly. “As a result,” he said, “I’ve been getting my hands through too quick and hitting to right – same as a slice in golf.”20 And, he said, he “probably [had] been a victim of overcoaching in the minors; everyone had a new theory for me to experiment with.”21

Tappe and two other players, infielder Vern Morgan and pitcher Don Kaiser, underwent special muscle tests at the University of Illinois on April 6, 1955. After Dr. Thomas Cureton studied the athletes’ muscle structure, he prescribed exercises and diets to improve the players’ power and endurance.22 The doctor’s advice, however, didn’t help Tappe’s hitting. He got into just two games for Chicago before rosters were cut down in May. That ended the brief run as teammates with Ted Tappe (no relation).

Tappe hit .230 in 45 games for Beaumont (then a Milwaukee Braves affiliate) and .121 in 62 games for Los Angeles in 1955. He recorded his only home run of the season in an 8-4 loss to the Shreveport Sports on June 26. The Angels were in seventh place when Tappe arrived in Los Angeles in early July, but the team was not eliminated from the PCL race until the next to last day of the season

Despite his lackluster bat, Tappe won plaudits with Los Angeles in 1955. “There are two factors in determining the value of a catcher, receiving and throwing, and receiving is divided into several departments,” Angels’ publicist George Goodale said. “As a general behind the plate, Tappe is as good as they come.”23 Baseball observers also noted that Tappe was particularly adept at shifting positions, providing a target, and getting the “strike” call on close pitches. In fact, toward the end of the ’55 season, Chicago Tribune sportswriter Richard Dozer said Tappe was “looked upon as a promising star.”24

During the next offseason, Tappe crumbled bits of newspapers into tiny balls to strengthen his hands and improve his hitting.25 “I figured it was the best exercise I could take to strengthen my hands,” Tappe told a Fort Worth newspaper. in the spring of 1956. “I have good shoulder and arm strength, but my hands have always been weak. I have to get better control of the bat. That paper squeezing routine may sound silly if you never tried it, but I believe it has helped me.”26

Tappe was one of seven catchers on the Cubs’ roster after the team obtained lefty-hitting backstop Hobie Landrith from Cincinnati in a trade for pitcher Hal Jeffcoat on November 29, 1955, at the winter minor-league meetings in Columbus, Ohio.27 Tappe spent most of his time with Los Angeles in the Pacific Coast League in 1956.28

“If Tappe could hit even .220 or .230 in the National League, he would go down in history alongside the Bill Dickeys and Mickey Cochranes. El is one of the greatest defensive backstops the game has ever known,” Los Angeles manager Bob Scheffing said in April 1956. “I remember the first three weeks Tappe was with the Angels last season. He hit something like .125, but his work with the pitchers was probably responsible for our winning about a dozen ball games.”29 Tappe hit .267 in 100 games for the PCL-champion Angels. He was also named to the league’s all-star team.

Tappe remained with L.A. the next season even though the franchise had been bought by the Brooklyn Dodgers – whose crafty owner, Walter O’Malley, thus obtained the rights to having a big-league club in Los Angeles. Tappe hit .182 in 79 games for the Angels, most of any by the four catchers the team used that year. He spent time on the disabled list in August with a badly swollen right thumb.30

Tappe started the 1958 season with the Cubs. On April 24, his single broke a 3-3 tie in an eventual 6-5 win against the Dodgers, who by then were in Los Angeles. He collected two more singles in the Cubs’ 15-2 victory the next day. Chicago outfielder Lee Walls hit three home runs and drove in eight runs in the lopsided contest. However, Tappe started only four of his team’s first 12 games, and he appeared in only 17 of the team’s 68 games through his last appearance on July 4. He batted only .214 in those games. Tappe was placed on waivers on July 23 so he could join the Cubs’ coaching staff.

Tappe served as a coach for the fifth-place Cubs from July 23, 1958, through the end of the 1959 season. He returned to the field in 1960, batting .233 in 51 games.

In 1961, Tappe had a major role in a revolutionary decision by owner P.K. Wrigley to replace the traditional manager with a system of rotating coaches at the major- and minor-league levels. When summoned by Wrigley at the end of the 1960 season, Tappe told the Cubs’ owner, “You’re making too many changes. Every time you make a managerial change, you make a pitching coach change and all coaching staff changes. We’ve got to systemize the thing.”31 In turn, Tappe suggested hiring a group of coaches who would remain as coaches no matter who filled the manager’s position. He also volunteered to write a book outlining the Cubs’ way so that the same methods would be used throughout the organization.

But Wrigley took Tappe’s suggestion one step further. “The college of coaches was my idea, but the Cubs made a fiasco out of it,” Tappe said years later. “The mistake was when Mr. Wrigley rotated the managers [head coaches]. I just wanted to rotate the coaches. I wanted to get hitting and pitching instructors to coach our players in the minor leagues and major leagues. Everybody is doing that now.”32

The Cubs conceded in their Official 1962 Press TV Radio Roster Book that the new system probably wouldn’t help the major-league club for at least three years. “The whole idea is to help the young prospects in the lower classifications,” the Cubs explained.33

Tappe served as head coach three different times and compiled a 42-54-1 record in the first year of the often-ridiculed experiment. Vedie Himsl, Craft, and Lou Klein also shared the head coaching duties throughout the season.34 Despite finishing in seventh place with a 64-90-2 record, future Hall of Famer Billy Williams was named Rookie of the Year. Another eventual Hall of Famer, Ron Santo, was chosen sophomore of the year. Even though the Cubs were the only team with a winning record against the pennant-winning Cincinnati Reds, they led the National League in errors and runs allowed.35

The Cubs had only three head coaches in 1962 – Tappe, Klein, and Charlie Metro, who replaced Craft after Craft was named manager of the expansion Houston Colt .45s. The Cubs got off to a 4-16 start under Tappe and ultimately finished ninth with a 59-103 record for a .364 winning percentage, their worst mark in the club’s 87-year history to that point (subsequently tied by the 1966 squad).36 Tappe returned to active duty on May 21, 1962, in Pittsburgh to beef up the catching corps when Dick Bertell became unavailable because of Army duty.37 The 35-year-old hit .208 in 26 games in his final season as a major-league player.

Later, Tappe credited the College of Coaches with developing the 1969 Cubs team that was overtaken by the New York Mets in September in the National League pennant race.38 Author John Skipper, however, said that gives too much credit to Wrigley’s two-year experiment. “The vast majority of the best players were with the Cubs before or came to the Cubs after the system was used,” Skipper observed.39

In 1963, Tappe guided the Cubs’ Triple-A affiliate, the Salt Lake City Bees, to a fourth-place finish in the Pacific Coast League’s South Division. The Bees finished 73-85. The next season, the Wenatchee Chiefs finished last in the Class A Northwest League with a 57-83 record under Tappe and Art Thompson. Tappe also scouted for the Cubs through 1975. Although the Cubs traded outfielder Lou Brock in 1964, Tappe tried to talk the Cubs’ management out of dealing the youngster to the rival St. Louis Cardinals, Tappe’s wife said 54 years later. “He got outvoted, and he maintained it was the worst trade the Cubs ever made,” Donna Tappe said at a fundraiser for the Western Illinois Fellowship of Christian Athletes in 2018.40

Tappe received the Fritz Ostermueller Memorial Award from the Quincy Elks on January 25, 1961. The award was named after a Quincy native and lifetime Elk who compiled a 114-115 record in 15 seasons with the Boston Red Sox, St. Louis Browns, Pittsburgh Pirates, and Brooklyn Dodgers. A story in the Quincy Herald-Whig six days earlier noted that Cub starting pitchers averaged 7 2/3 innings per start by mid-August 1960 after Tappe was restored to active duty as a catcher. The pitchers averaged only 2 2/3 innings per start when Tappe first served as a coach that season.41

Six years later, Tappe and his twin brother opened Tappe’s Sporting Goods in downtown Quincy’s east corridor. Tappe continued to operate the business for a while with the help of Mel’s sons, Ted, Tim, Tony, and Marty. “The transition to the sporting goods store … well, that was the typical El,” longtime friend Bill Alberts recalled in 1998. “As long as he was working with people and sports, he was happy.”42 In July 2003, Tim and Tony Tappe closed the 36-year-old business as the majority of shopping had moved from downtown to the city’s east end.

The Tappe family suffered a loss when El and Donna’s son Steven was found dead in a hotel in Nogales, Mexico (about 50 miles from his home in Tucson, Arizona) on March 6, 1976. The cause of death was cardio-respiratory arrest caused by heroin overdose, according to a Mexican coroner’s report.43 At the time, Steven was reportedly on a job for his employer, a tennis court contractor.

On June 11, 1977, Tappe was inducted into the Quincy College Sports Hall of Fame during an alumni weekend banquet at the college. The honor recognized his four years as a starter on the Quincy College basketball team and one year as a catcher on the college’s baseball team. He was also a charter member of the Quincy High School Sports Hall of Fame.

After retiring from baseball, Tappe did play-by-play for WTAD-AM radio and worked for television station KHQA in Quincy, “He was a lot of fun to be with,” longtime friend Alberts said. “He was the kind of guy that liked everybody, every place all the time.”44

Tappe died on Saturday, October 10, 1998, at his home in Quincy after a five-year battle with pancreatic cancer. He was survived by his wife, son Stanley, daughter Tammy, sister Winona, a sister-in-law. two grandchildren, and nieces, nephews, aunts, and cousins. Funeral services were held in Quincy the following Wednesday, and he was buried at Quincy Memorial Park. His brother Mel had died in 1992.

Reflecting on Tappe’s death, longtime Quincy Herald-Whig sports editor Chuck Brady called his Quincy College classmate “a tremendous all-around athlete.”45

Tappe was still getting eight or nine autograph requests per week two years before his death, which he always accepted without charging. “I would never charge for my autograph … I’m just thrilled that people want it. A baseball player who would take $25 for his autograph from, say, a guy who has two children, thus he has to get two signatures ($50), and yet has trouble making his house payments but wants to be a good dad … that’s wrong.

“I just wasn’t brought up that way – to charge for autographs – and don’t believe in that. Maybe I’m from the old school. To me, it’s like stealing, stealing on your success. Evidently a lot of guys don’t feel that way, but I do.”46

Even though Tappe is not in the National Baseball Hall of Fame, he is remembered fondly by many Cub fans for his contributions to the organization and his hometown of Quincy, Illinois.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Gregory H. Wolf and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Don Zminda.

In addition to the sources listed below, the author used Elvin Tappe’s player profile at the Baseball Hall of Fame Museum and Library, the Quincy Historical Newspaper Archive on the Quincy Public Library website at quincylibrary.org, baseball-reference.com, findagrave.com, ancestry.com, and newspapers.com.

Notes

1 Ross Forman, “Old-Timer Elvin Tappe remembers the game the way it was (and should be),” Sports Collectors Digest, February 23, 1996: 170.

2 Elvin’s paternal grandfather, Frederick William Tappe, was a musician and tailor and died in Quincy in 1897 at age 32. His paternal grandmother, Amelia Feld Tappe, a quilter, died in Quincy in 1938 after a long illness.

3 Bob Gough, “Friends remember El Tappe as tremendous athlete, leader,” Quincy (Illinois) Herald-Whig, October 12, 1998: 12.

4 William Mussetter, “Field of Dreams,” Quincy Herald-Whig, July 30, 1992: 31.

5 “Tops Among Teens,” Chicago Tribune, May 12, 1946: 109.

6 The others were Simon and Felipe Luna of Del Rio in the Class D Longhorn League, Ed and Kenny Peacock of Sweetwater in the Longhorn League, and Don Dee Moore of Lubbock and Wiley Moore of Clovis in the Class C West Texas-New Mexico League. “Texas Baseball Proves Ability Runs In Family,” Longview (Texas) News-Journal, August 2, 1948: 7.

7 Chuck Brady, “Tappe’s Match Marriage, Career,” Quincy Herald-Whig, August 8, 1961: 12.

8 “Texans Split Double-Header With Henderson 6-1, 7-8,” Longview News-Journal, May 30, 1949: 7.

9 Otis Harris, “As We Were Saying, “ Shreveport (Louisiana) Journal, August 25, 1950: 12.

10 “Tappe Not Seriously Hurt,” Fort Worth (Texas) Star-Telegram, June 26, 1951: 9.

11 Edgar G. Brands, “Minors Draft 162, Eight More Than Last Year,” The Sporting News, December 12, 1951: 7-8.

12 Braven Dyer, “Los Angeles Fans Love Him,” Quincy Herald-Whig, April 19, 1953: 36.

13 Dyer, “Los Angeles Fans Love Him.”

14 “Sky Sox, Chiefs Pace Stars,” The Sporting News, July 8, 1953: 34.

15 Edgar Munzel, “Cavvy Tabs Sauer, Baumholtz as Revolving Cub Right Fielders,“ The Sporting News, March 31, 1954: 10.

16 Tappe replaced catcher Joe Garagiola in the sixth inning and was replaced by Clyde McCullough in the seventh inning. https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1954/B04240CIN1954.htm. Accessed June 24, 2024.

17 Edward Prell, “Keegan Ends Argument With Sox and Signs,” Chicago Tribune, January 30, 1955: 36.

18 Paul Sisco, “Life Lines,” Berwyn (Illinois) Life-Beacon, April 6, 1955: 8.

19 “Tappe Battles Weakness To Stick With the Cubs,” Quincy Herald-Whig, March 31, 1955: 9.

20 “Tappe Battles Weakness To Stick With the Cubs.”

21 “Tappe Battles Weakness To Stick With the Cubs.”

22 Associated Press, “Three Cub Players Take Muscle Tests,” Terre Haute (Indiana) Tribune, April 5, 1955: 12.

23 George Goodale, “Few Catchers Better Than Tappe—Goodale,” Los Angeles Evening Citizen News, July 10, 1956: 14.

24 Richard Dozer, “Cubs’ Farmhands Impress Wid Matthews,” Chicago Tribune, September 13, 1955: 54.

25 Associated Press, “Elvin Tappe Trains On Old Newspapers,” Quincy Herald-Whig, February 28, 1956: 8.

26 Flem Hall, “The Sport Tide,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, March 1, 1956: 51.

27 The Cubs also drafted Monte Irvin, former New York Giants outfielder. Irvin finished his major-league career with the Cubs in 1956.

28 He also appeared in two games with the Cubs but did not bat. Elvin Tappe, Chicago Cubs Official 1962 Press TV Radio Roster Book (Chicago: Chicago National League Ball Club, 1962), 24.

29 Bob Kelley, “Bob Kelley Says,” Long Beach (California) Independent, April 25, 1956: 22.

30 Frank Finch, “Bilko Hits Homer but Angels Lose,” Los Angeles Times, August 2, 1957: 61.

31 Peter Golenbock, Wrigleyville: A Magical History Tour of the Chicago Cubs (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1999), 366.

32 Rick Van Blair, “El Tappe got to live his boyhood dream,” Sports Collectors Digest, January 8, 1993, 164.

33 “Some First-Hand Information About the Chicago Cubs Coaching System,” Chicago Cubs Official 1962 Press TV Radio Roster Book (Chicago: Chicago National League Ball Club, 1962), 36.

34 John Skipper, Take Me Out to the Cubs Game: 35 Former Ballplayers Speak of Losing At Wrigley (Jefferson, North.Carolina: McFarland, 2000), 219.

35 Rich Puerzer, “The Chicago Cubs’ College of Coaches: A Management Innovation That Failed,” The National Pastime, Society for American Baseball Research, Volume 26, 2006, https://sabr.org/journal/article/the-chicago-cubs-college-of-coaches-a-management-innovation-that-failed/, accessed July 18, 2024.

36 Skipper, Take Me Out to the Cubs Game, 219.

37 Elvin Tappe, Chicago Cubs Official 1962 Press TV Radio Roster Book, 6.

38 Skipper, Take Me Out to the Cubs Game, 219.

39 Skipper, Take Me Out to the Cubs Game, 219.

40 Ashley Szatala, “Quincy visit like old times for Hall of Famer Brock,” Quincy Herald-Whig, April 9, 2018: 1.

41 “Elvin Tappe Is Named for Elks Ostermueller Award,” Quincy Herald-Whig, January 19, 1961: 9.

42 Gough, “Friends remember El Tappe as tremendous athlete, leader.”

43 “Two Quincyans found dead in Mexican hotel,” Quincy Herald-Whig, March 9, 1976: 1.

44 Gough, “Friends remember El Tappe as tremendous athlete, leader.”

45 Gough, “Friends remember El Tappe as tremendous athlete, leader.”

46 Forman, “Old-Timer Elvin Tappe remembers the game the way it was (and should be).”

Full Name

Elvin Walter Tappe

Born

May 21, 1927 at Quincy, IL (USA)

Died

October 10, 1998 at Quincy, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.