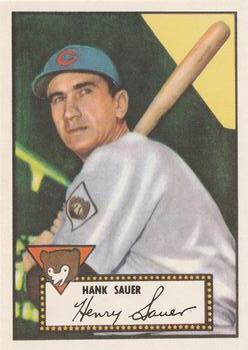

Hank Sauer

When the 1952 season ended, Hank Sauer, the heavy-hitting left fielder of the Chicago Cubs, had enjoyed a career year. Even though he averaged just .213 with three homers and seven RBIs during the month of September (due to a neck injury), the 35-year-old right-handed batting slugger was tied with the Pittsburgh Pirates’ Ralph Kiner for the major league home run title at 37. But Hank topped the majors in RBIs with 121, and his hitting helped lift Chicago to a fifth-place finish, the team’s highest since 1946.

When the 1952 season ended, Hank Sauer, the heavy-hitting left fielder of the Chicago Cubs, had enjoyed a career year. Even though he averaged just .213 with three homers and seven RBIs during the month of September (due to a neck injury), the 35-year-old right-handed batting slugger was tied with the Pittsburgh Pirates’ Ralph Kiner for the major league home run title at 37. But Hank topped the majors in RBIs with 121, and his hitting helped lift Chicago to a fifth-place finish, the team’s highest since 1946.

The Cubs saw paid attendance rise 130,411 above the team’s 1951 figure of 894,415. As a result, Chicago’s management gave Sauer – whose outstanding season was the most obvious reason for bigger crowds at Wrigley Field – his best contract ever: $37,500, a princely sum during a decade when the average big leaguer earned an annual salary of $12,340.

All smiles as he left the Cubs’ front office, the two-time All-Star came upon manager Phil Cavarretta in the hallway. Cavarretta was telling reporters that only five active big leaguers had lifetime slugging percentages over .500. Those power hitters were Stan Musial, Ralph Kiner, Johnny Mize, Larry Doby, and Hank Sauer.

Two weeks later the Baseball Writers Association of America’s 24-man committee, composed of three sportswriters from each of the National League’s eight cities, selected Sauer as the NL’s Most Valuable Player. The Pennsylvania native received 226 points in the voting, outpolling ace hurler Robin Roberts of the Philadelphia Phillies (28-7, 2.59 ERA) who had 211 points, and rookie right-hander Joe Black of the Brooklyn Dodgers (15-4, 2.15 ERA) with 208.

Thousands of older Cubs fans remember the MVP winner as one of the greatest sluggers – he smashed 288 regular season home runs – as well as one of the most modest fellows ever to grace the team’s uniform. Jerome Holtzman, the longtime Chicago scribe, wrote, “When Hank Sauer Was the Mayor of Wrigley Field” shortly after Sauer’s death in 2001. Holtzman labeled Hank “among the most popular players in Cubs history.”

Henry John Sauer’s struggle to live his baseball dream began in Bellevue, a Pittsburgh suburb. Born on March 17, 1917, he grew up in a working class family. After his father became ill, Hank helped his mother by running errands and cutting wood. All four sons, Fred, Bill, Hank, and Ed Sauer, later a four-year major leaguer, ate plenty of beans and soup in those days. Longing to see Pirates games at nearby Forbes Field, the Sauer boys would wait outside for a glimpse of heroes like Pie Traynor, Lloyd Waner and Paul Waner, and Arky Vaughan. Also, Hank was tough and a fighter. Later, he recalled his “nice guy” reputation in the majors came only after he learned to control his temper. “From an early age on,” he told author Danny Peary, “I was willing to mix it up.”

By age eight Hank was playing baseball behind a sausage factory with a rowdy bunch called the Quail Athletic Club. A modest, brown-haired, blue-eyed, spunky athlete, Sauer grew into a rugged 6’4” 200-pounder by the time he first glimpsed the major leagues in 1941. Along with his lanky, Lincolnesque appearance and a soft-spoken manner, he possessed excellent vision, good quickness, powerful wrists, and the muscular arms of a blacksmith, but he never had much speed. Later, the fans at Wrigley Field loved him. At every game, as a sign of affection, rooters in the “Sauer section” behind left field would toss tobacco to him. “Hank liked to chew,” former teammate Andy Pafko once observed, “and the fans showered him with pouches of tobacco!”

Sauer’s road to the big leagues was long and winding. After finishing high school in 1935, during the Great Depression, he worked at a federal Civilian Conservation Corps camp to help support his family. Returning home in 1937, he worked and, on weekends, played baseball. That summer Yankee scout Gene McCann spotted Hank playing third base in a sandlot game.

McCann arranged for Sauer to try out with New York’s Butler club of the Class D Pennsylvania State Association. After driving most of the pitches deep to left field, Hank signed for $75 per month. Fearing he might be considered too old, he listed his age as eighteen (he was twenty). Sauer did not admit his actual birth year until after he retired from the major leagues.

With Hank in the lineup, Butler topped the Penn State Association in 1937. The recruit first baseman batted .268 with three homers and 38 RBIs in 68 games. Returning to Butler in 1938, Hank became a hero, leading the league in several categories, including hits with 135, doubles with 29, and average with .351. Butler finished in first place and also defeated McKeesport in the playoffs, four games to one.

Sauer made steady progress in the minors. In 1939, the final season before World War II began in Europe, he batted .301 with 13 round-trippers and 92 RBIs for Akron of the Class C Middle Atlantic League. Promoted to Birmingham of the tough Class 1-A Southern Association in 1940, he averaged .292 with nine homers and 79 RBIs. That summer he courted Esther Tavel, and on December 29, 1940, he and Esther were secretly wed – because the Barons’ owner opposed young players getting married.

In 1941 Sauer enjoyed a fine season at the plate for Birmingham. Playing 154 games, he batted .330 with 19 home runs and 114 RBIs, but he also paced the circuit’s first sackers with 26 errors. The Cincinnati Reds had drafted Sauer that winter, and the ball club brought him up for a trial in September. The Reds had veteran Frank McCormick, a .299 career hitter, playing first base, and manager Bill McKechnie, who was defensive-minded, sent the agile Sauer to the outfield. He looked good, playing nine games and hitting .303, adding four doubles and five RBIs.

Baseball, like everything else in America, was changing, because the United States was drawn into World War II when Japanese forces attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii on December 7, 1941. At the time, Sauer appeared to be an up-and-coming talent, but in the Reds’ spring camp of 1942, he lost a fly ball in the sun. In those days, a mistake could prove critical to a young ballplayer’s career. “I missed one fly ball in spring training that year,” Sauer recalled in a 1995 interview, “and I was done. McKechnie sent me back to Syracuse, claiming I needed more experience.”

Discouraged for a time, Sauer persevered, playing two solid seasons for Syracuse of the Triple-A International League. Manager Jewel Ens, an excellent teacher of fundamentals, showed him the finer points of outfield play as well as how to control his temper. The big guy battled injuries in 1942, hitting only .213 with 11 home runs and 44 RBIs in 82 games. Healthy in 1943, he played the full season, averaging .275 with 12 homers and 75 RBIs.

During the war, Sauer, like the majority of professional athletes, left his baseball career on the sidelines and served his country. He spent 1943 and 1944 with the Coast Guard. Mustered out in mid-1945, he returned to Cincinnati and Crosley Field to finish the last wartime season.

Sauer swung a potent bat, but again it seemed to do him little good. For 31 games in 1945, he averaged .293, including five home runs and 20 RBIs. However, during a slide into third base, he tore tendons in his ankle. His season was over, he was optioned to Syracuse for 1946, and he never recovered his running speed.

At now Double-A Syracuse in the first postwar season, the hard-hitting Sauer produced a good year, hitting .282 with 21 four-baggers and 90 RBIs. The manager, however, believed Sauer’s power production could be improved, and his belief led to an experiment with Hank’s bat.

“Finally, I got that heavy [36-inch] 40-ounce bat,” Sauer recollected in 1995. “Jewel Ens, the manager at Syracuse, got me to use that big bat. Jewel said, ‘Just give it ten days.’ I gave that 40-ounce bat ten days, and that’s when I had that tremendous minor league year. I’ve used it ever since. That heavier bat got me in the big leagues to stay. I was hitting a lot of home runs, but most of them were fouls. That’s why Jewel wanted me to use the big bat. He said, ‘Hank, you’re a good contact hitter, but you’re so fast with that bat that you’re going to have to get something to slow you down.’ So he ordered the 40-ounce Chick Hafey bat.

“From that day on, I still got around fast enough to pull the ball. I was already a pronounced pull hitter. That’s [the bat] what made me, and I give Jewel Ens all the credit in the world for it.”

Sauer’s impressive 1947 figures included a .336 average, one point below the International League’s leader, and 50 home runs, three behind Howie Moss of Baltimore. Sauer topped the circuit in hits with 182, runs with 130, and RBIs with 141. Now slower, he belted 28 doubles and fielded a solid .983, racking up 12 assists with his strong arm. The Sporting News named him Minor League Player of the Year.

Saur made the big leagues to stay in 1948, playing as the regular left fielder for seventh-place Cincinnati. The 31-year-old rookie batted .260. Using his hard, looping swing to launch towering shots, he crashed 35 home runs, fourth best in the league, and he produced 97 RBIs, easily leading the ball club in both categories.

In 1949, however, Sauer struggled trying to continue Johnny Neun’s directive of hitting more to right field. On June 15, 1949, the major league trading deadline, Hank was hitting just .237 with four homers and 16 RBIs. Cincinnati, making one of the team’s worst trades ever, swapped Sauer and Frankie Baumholtz to the Cubs for “Peanuts” Lowrey and Harry Walker.

“Cincinnati kept hollering about wanting somebody with power,” Sauer remembered in 1995. “They got me in 1948, and I hit the 35 home runs. The manager [Johnny Neun] says, ‘Hank, we’re going to have to get you to hit a few balls to right field.’

“I said, ‘You know something. I was in the Yankee organization when I first broke in. They told me they wanted me to be a pull hitter. So the manager kept pitching to me, and I became a pronounced pull hitter. So I began hitting home runs. I said, ‘You asked for a home run hitter, and you got one. And now you want to make a Punch-and-Judy hitter out of me.’”

Sauer got off to a slow start and was traded to Chicago, where he was a better fit: “When they traded me to the Cubs, manager Frankie Frisch said, ‘Hank, I didn’t buy you to hit balls to right field. I want you to hit home runs and drive in runs for me.’ Well, that’s when I went crazy. I hit 31 home runs that year, and 27 of those came with Chicago.”

Sauer finished 1949 with a combined .275 average, 31 homers, and 99 RBIs. By comparison, Ralph Kiner led the loop with 54 round-trippers, and Stan Musial was second with 36. Even though he was more than thirty years old, Sauer didn’t want to be a team leader. He was a team player. Later, Hank said in Danny Peary’s We Played the Game, “I wasn’t a leader type and I didn’t want to get into that role. I didn’t want to be accused of popping off because I considered myself a star.”

Wrigley Field, however, was not an easy ballpark for hitting four-baggers. The center field bleachers were mostly full of men wearing white shirts, the dress custom of the time for male sports fans, meaning the white baseball was coming out of a white background. In addition, the breeze usually blew off nearby Lake Michigan and affected play, because the wind could suddenly blow hard and also change direction quickly. Sauer recalled one occasion when Pittsburgh’s Murry Dickson, pitching on a gusty afternoon with the wind coming from center field, said he would groove the ball and let Sauer hit away. Hank launched three blasts that would have been home runs, but they were blown back into play for outs. In his fourth trip, Hank said, “I hit the best shot of my life and it barely hit the fence.” Overall, Sauer had success at Wrigley, because he focused on the pitcher’s arm and ignored the white background. Even so, he told Danny Peary, “Guys like Stan Musial questioned how I could hit so many homers there.”

In 1951 the Cubs slipped after trading Andy Pafko in an eight-player deal to Brooklyn on June 15. Sauer was batting fourth with Pafko fifth, so that after the eight-player swap, Hank didn’t have a strong hitter batting behind him, and he believed other teams often pitched around him in big situations. Chicago fielded a close-knit team, Sauer recalled, except the younger players disliked manager Frankie Frisch, who was fired after several of them complained. In fact, most of the Cub players were pals off the diamond, and they would drink beer together or visit one another. “Most of the guys lived modestly on the North Side,” Hank said to Danny Peary, “and you’d usually have a companion or two going to and from the ballpark each day.”

Sauer traveled to California after the 1948 season to visit his brother Ed, who was then playing in the Pacific Coast League, and Hank never left. Instead, he lived in California and took part-time jobs in the off-season during his first five years in the majors, through 1952, when he signed for more than $37,000. He helped a carpenter in Hollywood, he appeared as an extra in movies and on television programs, and he took up golf, quickly becoming a scratch golfer. He also made a little money off endorsements each year, notably $1500 one time for his signature on a Wilson glove. Baseball cards were booming in the early 1950s, and he collected about $100 a year from the two card companies, Topps and Bowman. Hank signed a bat contract with Hillerich and Bradsby, but he received one set of golf clubs for allowing the company to use his signature each year. Such was the supposedly glamorous life of a star major leaguer in the postwar era.

In 1952 Sauer surprised many baseball writers and thrilled Cub fans by coming through with an MVP season, and his feats including hitting 37 homers, which tied him with Pittsburgh’s Ralph Kiner for the major league lead, and Sauer led the majors with 121 RBIs. Based on his performance, not only did the baseball writers select him as the National League’s MVP, but The Sporting News named him the circuit’s top player and chose him as for the weekly paper’s Major League All-Star team. What was unusual in 1952 was that Sauer became the first player on a second-division team – the Cubs finished in fifth place – to become league MVP.

However, “The Honker” (so called because of his large nose) ended the season in a slump that was caused by an injury. In mid-August, he slid into Red Schoendienst of the Cardinals while trying to break up a double play at second base. As the play ended, Hank fell on the back of his head, wrenching his neck. He returned to the lineup three days later. Even so, Sauer suffered muscle spasms and severe pain, he had no lateral vision at bat, and he couldn’t sleep for two months. Esther had to help him out of bed each morning. Somehow he blasted home run number 37 on September 11, 1952, and two weeks later Kiner hit number 37 to tie Sauer.

Over the winter, Sauer’s neck healed, but in 1953 he endured an off-season due in part to injuries. “In spring training,” Sauer said in 1995, “I broke one finger. On Opening Day, I broke another one. But I played with a splint. I just took those fingers off the bat. But when I broke my hand, I was out for six weeks there. And I came back too soon.

“A week after they took the cast off, I was playing ball. It really hurt. I told Phil Cavarretta, ‘Phil, I can’t even hold the bat right yet.’ Phil said, ‘Well, you hit better with one hand than most of these guys do with two.’

“So that’s the way I played. I had a poor year that year. I think I had 19 home runs, even hitting that way. That wasn’t too bad. You give me a couple hundred more at-bats, I would have still hit my 30 homers and knocked in 100 runs.”

Sauer asked, “You know why we came back too soon after injuries? Because we were afraid someone else would take away our job. That’s the way it used to be in the 1950s.”

In 1954 a healthy Sauer returned to form. In 520 official at-bats, he hit .288 and slammed a personal-best 41 four-baggers. Chicago, meanwhile, released Phil Cavarretta, the manager, and replaced him with Stan Hack, the former Cubs’ third baseman who starred on Chicago’s 1945 World Series team. But the managerial switch made little difference. Chicago finished seventh in 1954 and sixth in 1955.

Sauer enjoyed a better season in 1954 than his MVP season in 1952. He recalled, “You know what? They sent me a $1,500 cut in contract after the 1954 season. I said, ‘I don’t think I deserve a cut in contract.’ Finally, they gave me back the same contract I had in 1954. The front office said, ‘We could have ended up in seventh place without you.’ I said, ‘Yeah, but you wouldn’t have drawn a million people without me.’”

The Cubs did honor their fan favorite with a “Thank Hank Day” in 1954. Laughing about his day, Hank remarked, “You talk about throwing tobacco out on the field. That day they had to stop the game and send workers out to pick it all up! They filled seven or eight bushel baskets with tobacco pouches.”

During his first seven seasons, starting when he was thirty-one, an age considered “old” for a professional athlete during the time period, Sauer averaged .271, 32 homers, and 96 RBIs, all the while playing for second-division ball clubs. In 1955, partly because Chicago no longer used the aging hero as a regular, Sauer had another off-season. In Stan Hack’s second year as manager, the Cubs climbed one notch to sixth. But Sauer, playing in 79 games and batting 261 times, hit just .211 with 12 home runs and 28 RBIs. It was his most disappointing season.

“Wid Matthews, the director of player personnel, wanted to get rid of me,” Sauer recalled, “but [owner] Phil Wrigley said, ‘You can’t get rid of him. He’s going to be one of our organization men.’”

Still, Sauer’s worst season caused the front office to decide that he was too old, and on March 30, 1956, he was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals for outfielder Pete Whisenant and $30,000. In St. Louis, Hank roomed with Stan Musial.

Sauer, playing as a reserve in 1956, batted 151 times, but he averaged .298 with five home runs and 24 RBIs, despite being hit in the face with a bat during one of the team’s practice sessions. Also, he and his roommate stayed out until after midnight two or three nights a week, which, Hank recollected, Musial enjoyed.

The Cardinals’ management, however, did not favor late-night carousing. Sauer observed, “In September of ‘56, the manager [Fred Hutchinson] came up and said, ‘Hank, we’ve got to let you go.’ I said, ‘Let me go! I’m having a pretty damn good year. Why are you letting me go?’

“He said, ‘Yeah, you’re having a good year, but your roommate is having a lousy year. He’s only hitting .315.’ I said, ‘What the hell’s the matter with .315?’ He said, ‘Musial is not a .315 hitter. He’s a .330 hitter. You’re on your way!’ So I was the one who had to go.”

Laughing, Sauer added, “Wherever Stan Musial goes when he dies, I want to go, too. There’s not a better person in the world than Stan Musial. He’s just a tremendous guy. He’s just personality-plus.”

St. Louis released Sauer on October 16, 1956. Ten days later, he signed with the New York Giants and renewed his career in 1957. Covering left field at the Polo Grounds, the 40-year-old flychaser (on paper he was 38) won the Comeback Player of the Year Award for what became his last season as a regular. Sitting out the second half of twin bills, the likeable Hank played 127 games, averaged .259, hit 26 home runs, and contributed 76 RBIs to the sixth-place Giants.

Moving with the club to San Francisco in 1958, Sauer became a backup, hitting .250 with 12 homers and 27 RBIs. In 1959, he joined the coaching staff in mid-season, a move made by the Giants’ management in order to keep Felipe Alou from being sent to the minors.

Sauer served in different capacities for the Giants for thirty-five years. Based on his agreement with owner Horace Stoneham, Hank served as the club’s hitting instructor for ten years. The old slugger worked with the Giants’ hitters when they were at home and with minor league players while the club was traveling. Beginning in 1970, he became an assistant to the minor league director, Jack Schwarz. In effect, Sauer ran the Giants’ farm system, until the club “retired” him for a younger man in 1993. Like so many other longtime players before him, Sauer became a lifetime baseball man, able to work every day with the game he loved

Reflecting on his years as a major leaguer, Saur explained that two of his favorite highlights occurred in 1952. On June 11 at Wrigley Field, the big outfielder blasted three solo home runs off Phillies’ left-hander Curt Simmons, lifting the Cubs to a 3-2 victory over the pitcher soon named to start the 1952 All-Star game. Ironically, Sauer enjoyed his only other three-homer day on August 28, 1950, also against the fast-balling Simmons, when he led the Cubs to a 7-5 win. Sauer’s 1952 slugfest against Simmons made him the first major leaguer ever to hit three home runs off the same pitcher in two separate games.

The second highlight came on July 8, 1952, when Sauer became the biggest hero at the All-Star game, held on a rainy afternoon in Philadelphia’s Shibe Park. With his NL team trailing, 2-1, in the bottom of the fourth, Sauer, batting cleanup, stepped to the plate with Stan Musial, who had been hit by a Bob Lemon fastball, on first base.

“On Lemon’s next delivery,” wrote John Drebinger of the New York Times, “Sauer, currently the National League’s leading slugger with twenty-three homers, blasted the ball over the left field roof for just about as robust a clout as any mid-summer classic had seen.” Curt Simmons pitched the first three innings, and the Cubs’ Bob Rush, who hurled the last two frames of the rain-shortened game, won the contest, 3-2.

Of Sauer’s 38 total home runs in 1952, his All-Star shot was the most famous: “John Hillerich, president of the bat company, left the game early. He was driving down the street behind the left field stands, and he saw the ball I hit bounce in the street. He got out and paid $5 to the fellow who picked it up. Later, Juni gave that ball to me.

“The Baseball Hall of Fame called up, and I sent it to them. So I’m not in the Hall of Fame, but one ball I hit made it all the way to Cooperstown!”

Sauer enjoyed a very satisfying career, but he never has been seriously considered for the National Baseball Hall of Fame. However, he was proud of being inducted into the Halls of Fame of the Birmingham Barons, the Syracuse Chiefs, and the International League.

“I enjoyed playing alongside Hank Sauer, a great power hitter,” Andy Pafko later remarked. “I saw him hit three home runs at Wrigley Field off Curt Simmons. It was a great display of power, one to left field, one to center, and one to right field!”

If he had one regret about his years in baseball, Sauer remarked in 1995, it was that he was never able to play on a team that made it to the World Series.

Still, Sauer loved baseball, loved talking about the game, and loved hearing from the fans. He liked to point out, however, that today’s baseball business is different from the game they used to play. Reminiscing about his first trip to the majors in 1941, Sauer said: “That was a proud moment, putting on the uniform. Oh, boy, I walked a mile high! I was a tall man then. When you put on a major league uniform, you feel like a big man. The tops. Nothing higher.”

On August 24, 2001, the eighty-four year old Sauer died suddenly of a heart attack while he was golfing, which was his second favorite sport. He was survived by his second wife, Jeanne, whom he married in 1979, after Esther (Tavel) Sauer passed away.

Tall, friendly Henry John Sauer, a down-to-earth man of strength, determination, and grace, was in many ways typical of major leaguers during the postwar decade. Lawrence Ritter, in his Introduction to We Played the Game, commented on Sauer’s times: “In the forties and fifties, we sat in the afternoon sunshine and watched the likes of Joseph Paul DiMaggio, Ted Williams, Stan the Man, and Rapid Robert Feller – all of whom, by the way, spent their entire careers with one team – and with role models like them, it was no wonder just about all the sports idols of kids growing up were baseball players.”

Everyman’s ballplayer, Sauer worked to overcome the challenges he faced in life and baseball. Even though he lost two years to World War II, spent eight years in the minors, became a regular major leaguer when he was past thirty, adjusted and readjusted his hitting style, and came back from many injuries, the big Pennsylvania native persevered and won recognition as a two-time National League All-Star, the senior circuit’s 1952 MVP as well as home run and RBI champion, and a longtime Cubs fan favorite.

January 17, 2012

Sources

Jim Sargent, “Hank Sauer, Power Hitter: ‘The Mayor of Wrigley Field’ Revisited,” Oldtyme Baseball News, volume 8, issue 2 (1996), pp. 8-9, 22, was an earlier version of this article. Also see Jerome Holtzman, “Do You Remember … When Hank Sauer Was the Mayor of Wrigley Field,” Baseball Digest, December 2001, pp. 64-66. I talked with Sauer on several occasions, notably on July 22, 1995, and the quotes from Hank that have no other source indicated came from that telephone interview. Also, Sauer was interviewed at length for Danny Peary’s book, We Played the Game: 65 Players Remember Baseball’s Greatest Era, 1947-1964 (New York: Hyperion, 1994). Sauer’s clipping file in the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s Library contains a number of useful items. Also, his stats were derived from The Baseball Encyclopedia (Macmillan, 9th edition, 1993), Total Baseball (Sport Media Publishing, 8th edition, 2004), and Baseball-Reference.com. For information on salaries, see Michael J. Haupert, “The Economic History of Major League Baseball” (2010), posted on the web site of the Economic History Association: http://eh.net/encyclopedia/article/haupert.mlb

Full Name

Henry John Sauer

Born

March 17, 1917 at Pittsburgh, PA (USA)

Died

August 24, 2001 at Burlingame, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.