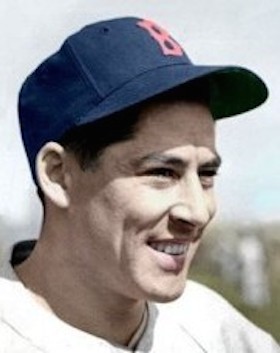

Eddie Lake

“Who the heck is Eddie Lake?” That is the title of a booklet written and published by Karen Elizabeth Bush in 2003. Bush is Executive Secretary of the Eddie Lake Society, an invitation-only society originally founded by Hall of Fame sportswriter Joe Falls. “We are made up of people who in some way or another have given as many as 40-50-60 years of their lives to baseball on and off the field,” writes Bush. “Joe’s only requirement for membership was that applicants love baseball. In recent years, this has been amended to ‘love baseball and respect and know the traditional game.’ Lake’s name was picked for the Society in part because he was so accessible to his fans, in part because – like so many of those fans – he was a blue-collar guy. With a total Society membership capped at 100, today 50-60 active members meet once a month (April – December) in Warren, Michigan.”

“Who the heck is Eddie Lake?” That is the title of a booklet written and published by Karen Elizabeth Bush in 2003. Bush is Executive Secretary of the Eddie Lake Society, an invitation-only society originally founded by Hall of Fame sportswriter Joe Falls. “We are made up of people who in some way or another have given as many as 40-50-60 years of their lives to baseball on and off the field,” writes Bush. “Joe’s only requirement for membership was that applicants love baseball. In recent years, this has been amended to ‘love baseball and respect and know the traditional game.’ Lake’s name was picked for the Society in part because he was so accessible to his fans, in part because – like so many of those fans – he was a blue-collar guy. With a total Society membership capped at 100, today 50-60 active members meet once a month (April – December) in Warren, Michigan.”

Lake was born in Antioch, California, on March 18, 1916 to California natives William Lake and Amelia (Acosta) Lake. “I’m a funny mixture of nationalities,” he mused. “I’m Spanish, Irish, and English. I suppose my swarthy complexion accounts for the blood of the noble Dons who were the first in California.”1 William Lake was a pipe fitter in a steel plant at the time of the 1920 census, when the family lived in Pittsburg, Contra Costa County, California. The Lakes had four children: Grace, Lyle, Edward, and Leabella.

At some point, William Lake was gone. In 1930, Amelia Lake was the head of the family working at ironing in a laundry.

Eddie went to the Cole School, Elmhurst Junior High, and Castlemont High School in Oakland, where he both pitched and played outfield, and was on the football and track teams. Lake had planned to become a cabinet maker.2

“He was thought to be too small for pro ball,” wrote Jack Malaney of the Boston Post.3 He is listed as 5-feet-7, weighing 170 pounds. St. Louis Cardinals scout Charley Remmers took a chance on him and signed him.4 Remmers may have first seen him at the Cardinals’ “observation camp” (a tryout) at Evans Park, Riverside, on March 2, 1937.5 “He’s a little guy,” Remmers wired Branch Rickey, “but think nothing of it. He’s big enough to powder that ball with the best in the organization.”6

In 1937, Lake played in the Class-D Nebraska State League for the Grand Island Red Birds, batting .297 over the course of 111 games with nine home runs. During the season Branch Rickey arranged for him to be converted to an infielder. “I liked the change from the start,” he said years later. “Ever since I’ve been an infielder, mostly a shortstop. That’s the job I like best.”7 He jumped two levels and played 1938 in the Class B Three-I League for the Decatur (Illinois) Commodores. He hit .279 in 125 games, and homered six times. His 112 bases on balls led the league.

In 1939, Eddie’s older brother, Lyle Lake, born in 1915, joined him as a professional baseball player. Lyle was a catcher who played two seasons for Spokane in the Class B Western International League. He hit .241 in 81 games in 1939, but only .182 in 33 games in 1940, his last year in pro ball due to his being drafted into WWII.

Eddie Lake was with the Houston Buffaloes in the Texas League, an A-1 circuit, the equivalent of Double-A ball in the early twenty-first century. Houston finished first, 8 ½ games ahead of Dallas and San Antonio. He acquitted himself well, playing the full season and leading the league in runs scored with 129. Though slight of stature, he homered 14 times. Again, he showed a patient eye at the plate, for the second year in a row leading his league in walks (153).

On September 9 his contract was formally sold to the Cardinals and he was brought to St. Louis. Lake debuted on September 26 in Cincinnati, as a pinch-runner for Johnny Mize. His first start was on September 30, playing shortstop and batting leadoff against the Cubs at Wrigley. Lake was 1-for-3, with a base on balls. He had another at-bat on October 1, but made an out.

Lake trained with the Cardinals at St. Petersburg and opened the 1940 season with the team, combining pinch appearances with second base and shortstop work. He got into 32 games, but one was spectacular enough to provide a memory to hold onto. The Brooklyn Dodgers were visiting Sportsman’s Park on May 7, 1940. Lake hit his first big-league home run – and his second (the only two he hit all year) – and drove in his first major-league runs. Five of them. St. Louis won the game, 18-2, setting a record at the time with 49 total bases. Lake was 3-for-6 with a double and the two long balls. But come June 23, he was batting only.212. On July 1, not having played in the interim, the Cards sent him to the Sacramento Solons (Pacific Coast League), where he batted .295 with 15 homers in 69 games. Though he’d played just a half-season, noted sportswriter Bob Ray of the Los Angeles Times selected him as utility infielder for a PCL all-star team.

Lake was never unhappy to be assigned to Sacramento. He had married Verla McCarter of Oakland in March 1937. The two later had a daughter named Patricia (born on St. Patrick’s Day) and another named Donna.

He played all of 1941 for St. Louis, but it was a dispiriting year. He hit just .105 in 92 plate appearances scattered over 45 games – just eight hits, two of them doubles, over a full big-league season. He didn’t drive in a run all year long. And his error at shortstop with the bases loaded in the 13th inning cost the Cards a loss to the Pirates on August 9. He played third base, short, and second, committing three errors at each position. When he wasn’t playing, he was often used to warm up pitchers in the bullpen.

Lake decided he’d rather play in the minor leagues that have another season like that. Karen Bush writes, “When the spring of 1942 came around, he flatly refused to report to the Cardinals, making the rather unusual request that he be reassigned to the minors. In fact, he said, he would go back to work in a steel mill not far from his mother’s home in Oakland, if baseball didn’t send him to Sacramento.”8 Branch Rickey reported, “He wants to go to a Double-A club for $150 a month less than he’s been getting from the Cardinals. Never knew of a case like it.”9 We might keep in mind that this unfolded within a relatively few weeks after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor plunged America into war, and playing closer to home might have additional appeal as well. Lake said he wanted to play baseball and hadn’t started even one game in 1941. “That’s all there is to it.”10

On April 8 he joined the Solons. The Coast League had a much longer season, and Eddie played in 176 games for Sacramento in 1942, far more enjoyable than sitting on the bench. He batted .278 with 19 homers. Sacramento finished first in the standings, one game ahead of the Los Angeles Angels. Lake led the league with 118 runs scored. With 107 bases on balls, he had a .385 on-base percentage.

Lake was still on a St. Louis Cardinals contract. With the Red Sox losing a significant number of players to military service, including Ted Williams and star rookie shortstop Johnny Pesky (.331, a league-leading 205 base hits, and ranking third in league MVP voting), Boston wanted to shore up shortstop for 1943. On September 8 the Red Sox purchased Lake’s contract from the Cardinals for a sum understood to be $25,000, calling for delivery in 1943.

Lake believed he was going to be able to play for the Red Sox, and not just warm the bench. He said, “It called for a little cap-tossing in the air.”11

Regarding his moves with the Cardinals, he remarked to John Drohan of the Boston Traveler, “I tell you joining that Cardinal organization is really a liberal education in itself; you discover towns and places you never ever read about in geography.”12

He and Skeeter Newsome were to compete for the position during spring training, though the job was really Lake’s to lose. Near the end of March, he contracted German measles and was placed in “virtual quarantine,” isolated from the rest of the team. The disease did not spread.13

Newsome ended up with the lion’s share of the playing. Lake batted .199, playing in 75 games, and drove in 16 runs on the season, six of them in back-to-back games in late June during 6-5 and 7-1 wins in Philadelphia. His ninth-inning double off Early Wynn won the May 7 game against the Senators. Thanks to 47 bases on balls, he recorded a .345 on-base percentage, and he scored 26 runs.

He’d talked about wanting to pitch (which he hadn’t done since high school) and almost worked in an exhibition game against Camp Grant at Rockford, Illinois, but the game had to be canceled so the Red Sox could make up a postponed game against the White Sox. On August 31 he pitched seven innings against the U.S. Army team at Camp Shanks, New York, allowing eight hits and winning the exhibition game, 10-1.14

In 1944 he got his chance to pitch in a regulation game. He did marginally better at the plate, batting .206 (with only eight RBIs) but had the uncommon opportunity to actually pitch not just one time but in six games. The 5’7” infielder had thrown a half-hour of batting practice on May 17, but Joe Cronin stuck him on the mound in the sixth inning of the second game of that day’s doubleheader, after the Browns had posted nine runs.

Lake pitched 2 1/3 innings. He gave up three hits, walked two, struck out one, and made a fielding error as pitcher. Three runs scored, but the Boston Globe’s Harold Kaese was impressed: “Compared with most Sox pitchers, Lake has a lot of stuff on the ball and if handled like a pitcher, he probably would prove as effective a game-finisher as Cronin has.” The Globe ran a story the next day headlined, “Cronin Sees Eddie Lake as Sox Mound Prospect.”

A couple of weeks later, on June 2, Lake was called upon again and pitched no-hit ball for two innings. On June 23 he threw the final four innings, yielding three hits, one run. He had a double at the plate. His longest mound stint was on July 5, when he pitched the final six innings; in the process, though, he yielded six hits and three runs.

On July 9, “Sparky” Lake pitched the final three innings. Five hits, three runs. And in his last time on the mound — July 16, he threw the final two innings, matching his shortest stint of the year. He gave up two hits and hit two batters.

All told, his line as a pitcher was 19 1/3 IP, 20 hits, two HRs, 11 BB, seven K, and an almost respectable 4.19 ERA. (The league ERA was 3.40.) The next time he pitched was seven years later, in the minors in 1951.

There wasn’t much reason to think the Red Sox would want him back in 1945, based on his ’43 and ’44 seasons, and indeed he didn’t even come east for spring training. He hadn’t been called into the service but he was working 10-11 hours a day at a defense plant in California. But when the Sox lost the services of Bobby Doerr and Jim Tabor to the war, Lake was summoned east, arriving on April 17. Two days later, he pinch-ran in a game, then first played the infield on April 29. He didn’t get a start until May 27; he singled and drew three walks in eight plate appearances during the day’s doubleheader, and handled 14 chances at shortstop, helping Boo Ferriss preserve a one-hitter in the first game.

In late May, Newsome had been hurt in a play at second base and that gave Lake his shot, in a reshuffled infield. Starting on May 28, he put together a 10-game hitting streak, bumping his average up from .000 to .390 (with a .510 on-base percentage). There was no way Joe Cronin was going to take him out of the lineup at that point. Lake showed hustle, too, a trait highly-regarded at the time. “Despite his rare appearances in games, ‘Inky’ has kept up his hustle and chatter during practice and from the dugout, and is the sort of boy you like to see in there every day.”15

There was another hitting streak, 11 games, from June 19 through July 2. All in all, the way Lake had become red-hot was just “one of those unexplainable things in baseball.”16 He played the rest of the season, 130 games at shortstop. He cooled off as a batter, but put up a respectable .279 average, with 51 RBIs – third on the team. He hit 11 homers; only Bob Johnson hit more (12). By late July, he had already homered more times than in his prior career to date. Lake credited Bob Johnson’s suggesting he “move back in the batter’s box and use his powerful wrists more.” Lake said, “Playing regularly lets me look at more pitching and those few inches I backed up give me a better chance to watch the ball.” Alright, but what about the home runs? “I dunno, I just poke it if it’s in there.”17

Most notably, he earned 106 bases on balls. Added to his base hits, Lake led the American League in on-base percentage at .412. His 459 assists from shortstop led the league, as did the 112 double plays he helped turn. The Red Sox set a major-league record with 198 double plays in 1945.18 It was by far Lake’s best year.

With Johnny Pesky coming back from the service, Lake had become surplus but still a valuable commodity. There was talk about swapping him to Washington for outfielder George Case, but just as the new year began, the Sox sent him to the reigning World Champion Detroit Tigers on January 3 for Rudy York. Of Lake, the Boston Herald observed, “He had little chance to be [the first-string shortstop] this year, with Johnny Pesky coming back….As the Sox felt they could let Lake go, so did the Tigers figure that they could strengthen a weak spot by letting York go, since it’s generally conceeded [sic] that Hammering Hank Greenberg will be back at his old first sack berth for the ’46 Tigers.”19

Even before the season began, though, prognosticators picked the Red Sox to win the pennant in 1946, not the Tigers. They had Ted Williams coming back, and Pesky, and Doerr and Dom DiMaggio and so many others. Indeed, they ran away with the pennant from the get-go.

Eddie Lake could never say he hadn’t got his chance to play, appearing in 155 games in 1946 for manager Steve O’Neill and the Tigers — every game the team played. He hit .254, and walked 103 times, for an on-base percentage of .369. He drove in 31 but he scored an impressive 108 runs, third-best in the American League. His 703 plate appearances led the league, but his 35 errors at shortstop were second highest.

He picked it up in 1947 with a good April, but by May 12 had dropped under .200 and didn’t reach it again until June 30. It took a 10-game hitting streak in mid-July to get him to .220. By season’s end, he was at .211, a drop-off that is difficult to understand. It wasn’t for lack of playing time; the Tigers played 158 games (there were four tie games) and Lake was in every one. Why did he struggle so? Karen Bush suggests that the emergence of a couple of fellow infielders on the Tigers may have affected him. Both third baseman George Kell (.320, 93 RBIs) and first baseman Roy Cullenbine (24 HRs, 78 RBIs, despite a .224 batting average) had very good years, and Lake may have been trying too hard to keep up. He did hit 12 homers, his career high, but it may have been at too great a cost. Even though Lake walked 120 times, Cullenbine drew 137 walks. Bush wrote, “It was heady company for Eddie to be keeping, and he felt the pressure.”20

His 43 errors led the league, though that also reflected the number of chances he had due to playing in so many games; he also led the league in putouts, with 508.

The following spring, an unnamed veteran in the Tigers clubhouse said of Lake, “He’d be a lot better off if he wasn’t home-run sluggy. He thinks he’s a home-run hitter and he stands up there and keeps swinging for the stands. If he doesn’t knock one out of the park for a couple of weeks he broods and his fielding falls off. The guy can’t weigh more than 137 pounds. He’s so small that they nicknamed him ‘Jockey’ in the minors. If he’d get over this home-run complex of his and just try to meet the ball, he’d hit at least 50 points higher.”21

Lake may have taken the advice to heart. He wasn’t as “home-run sluggy” in 1948 (he hit only two), and he did hit almost precisely 50 points higher — .263 to the .211 he’d hit in 1947 – but he also hadn’t played nearly as much. He was late to sign (March 17, the last on the club to come to terms) and then his wife’s illness held him back a couple more weeks. He didn’t start his first game until May 9. There had been rumors of trades including Lake at the tail end of the 1947 season, and an Associated Press story in April 1948 dubbed him as “wearing an excess-baggage label.”22

Johnny Lipon had secured the starting slot at short. Lake played third base in May, and then filled in at second base for an injured Eddie Mayo from that point on, until he suffered his own injury. On August 24, during the fourth inning of the game against the Athletics at Shibe Park, he took a throw from Lipon as the baserunner crashed into him at the second-base bag. The third finger of his left hand was broken in two places.23 He was out for the rest of the year.

Quick to sign in 1949, he had an entirely lackluster season. Though he appeared in 94 games (missing a significant number in both June and July), he pinch-hit or pinch-ran in a number of the games. He was at shortstop in 38 games, and split 37 games almost equally between third base and second. His best contribution at the plate was in taking bases on balls; he hit for just a .196 average but walking 61 times boosted his on-base percentage to .359. Lake drove in 15, and scored 38 runs. He hit one home run, his last in the majors.

Oddly enough, one of the most notable things he did was to ground into a double play his last time up. The Tigers were in fourth place, and winning or losing the October 2 season finale wasn’t going to make a difference in the standings. The Cleveland Indians were at Briggs, and a huge crowd of 51,714 had come out to see the arguably otherwise-meaningless game, a matchup between Bob Feller and Virgil Trucks. They were there to see if George Kell could possibly win the batting title.

Cleveland was leading 8-4 going into the bottom of the ninth. With one out, Dick Wakefield pinch-hit and singled. Eddie Lake was up next, already 0-for-4 on the day. Waiting in the on-deck circle as Lake stepped into the batter’s box was George Kell.

Kell had been .341 coming into the game, and Ted Williams of the Red Sox was, rounded up, .344. It looked like Williams was poised to win another batting title – and a third Triple Crown. But Williams was 0-for-4 on October 2, and Kell was 2-for-2 through the fifth. He walked in the sixth and then flied out in the seventh. He was leading the American League in batting average, but only by a razor-thin margin over Ted Williams of the Red Sox. Kell’s average was .3429118. Williams was .3427561.

Had Ted sat out his final at-bat and not flied out to center field in the sixth, he would have held an edge – but not known whether Kell would hit or not. Sitting out was no option; a Red Sox win would have given them the pennant and they were down 1-0 against the Yankees at the time. Tigers manager Red Rolfe could have sat Kell – the Red Sox game was over and the Sox had lost. Kell said he would take his chances and was indeed in the on-deck circle. Whether Rolfe would have pulled Kell at the last moment will never be known. Had Kell batted and made an out, he would have been .3422562, and lost the title.

Eddie Lake grounded into a game-ending double play. Kell was the American League batting champion.

Lake’s last season was 1950. Even though he appeared in 20 games, spread throughout the season, he didn’t get even one base hit. He pinch-hit nine times and pinch-ran nine times. He filled in late in one game at third base and another at shortstop. Though pinch-hitting nine times, he only had eight plate appearances. In the June 26 game in Detroit, the Tigers were down, 4-1, heading into the bottom of the eighth. They scored three times to score and had runners on first and third with two outs. Lake was sent up to pinch-hit for pitcher Hal White. But the White Sox brought in a new pitcher, so Red Rolfe had Charlie Keller pinch-hit for the pinch-hitter Lake, and Keller tripled to give the Tigers a 6-4 margin, enough to win the game.

Lake did walk once (giving him a .125 on-base percentage) and he drove in one run, with one of his outs. He scored three runs. It was no surprise to anyone that the Tigers cut him loose before the 1951 season. What may have been a surprise is that they had sent him a contract, but the proffered deal cut him from $10,000 to $7,500 and he decided to hold out. In the meantime he was “conducting his own spring training practice at the San Leandro ball park near his home.”24 But “the manpower shortage being what it is,” Rolfe apparently wanted “this seemingly useless fugitive from the junk pile” (in the words of Ed Gardner of the Washington Daily News.)25

On April 5, Lake’s contract was sold outright to the San Francisco Seals. Lake was far from useless to manager Lefty O’Doul of the 1951 Seals. He played 84 games at second base, 73 at third, and four at shortstop. He hit for a .261 batting average, homering 27 times (eight more than any other season, with 18 of the homers at Seals Stadium) and drove in 58 runs. He led his league again in walks, with 112. But the Seals finished in last place.

On February 23, 1952, the Oakland Oaks traded pitcher Wes Bailey and infielder Jimmy Moran to the Seals “in return for the Seals crack infielder, Eddie Lake….Lake, an ex-major leaguer last with Detroit, had been involved in a dispute with Paul Fagan, president of the Seals, over a bonus he claimed had been promised him if he had a good season last year.”26 He said that former Seals GM Joe Orengo had been the one to make him the promise.

Oakland actually tried Lake out in center field, and in right, but for the most part he played shortstop. He even pitched eight innings over four games (he’d pitched a couple of innings for the Seals in 1951). He never sufficiently impressed at anything, however, and only appeared in 47 games, batting .210. His season ended on June 7 when his right wrist was fractured as he tried to tag Sacramento baserunner Ed Roberts at second base.27 Over the holidays, the Lakes welcomed a son to the family.

He rejoined the Oaks in 1953 as a utility infielder, and got a fair amount of work, hitting .225 while appearing in 105 games. Come 1954, he was left high and dry and looking for a job; he wasn’t sent a contract. As he explained in March, “After last season when I had a couple of chances to manage small clubs, Oakland wouldn’t give me a release. Then I don’t get a contract so I am out all the way around.”28 He ended up in A ball, playing in the Western International League for the Victoria Tyees. He hit .276 in 89 games.

The league disbanded after the 1954 season, replaced by the Class-B Northwest League, and the Spokane Indians hired Lake as manager for 1955. He assigned himself to play in 80 games and hit for a .336 batting average, second on the team. Spokane finished in last place in the seven-team circuit. In 1956 he managed the Class C Salinas Packers (California League.) He hit .312 in 119 games, his last games in professional baseball. He walked 101 more times. There were eight teams in the league; Salinas finished seventh.

In each of his last six years in the minors, Lake pitched in one or more games, for a total over the six seasons of 13 appearances.

In 1959, Lake got into scouting and worked that year for the Washington Senators, followed by 1960-1962 for Minnesota, and 1968-1970 for the Detroit Tigers. In 1965 he had signed on as baseball coach for the noted St. Mary’s of Moraga, California. For 1965 and 1966, the most frequent appearance of “Eddie Lake” in newspapers was that of a racehorse that entered numerous races.

Lake spent a few weeks in both 1969 and 1970 working in Mexican baseball, conducting a series of baseball clinics, for the Mexico City Reds in 1969 and the Union League clubs at Queretaro in 1970. After 1970, he retired from baseball.

On June 7, 1995, he died at the Baywood Nursing Facility in Castro Valley, California. He was 79 years old, and had died from generalized nodular Hodgkin’s disease some 10 weeks after surgery. He is buried in Holy Sepulchre Cemetery in Hayward, California.

Keeping alive the memory of Eddie Lake is the Eddie Lake Society, with a core membership of 100 and an outreach nearing 200.

Last revised: May 6, 2021 (zp)

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Lake’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks to Karen Elizabeth Bush.

Notes

1 John Drohan, “Lake Helped Martin Win Pennant at Sacramento,” Boston Traveler, March 24, 1943: 24.

2 American League player questionnaire, Eddie Lake player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

3 Wilbur Adams, “Between the Sport Lines,” Sacramento Bee, August 8, 1945: 10. The Bee reprinted Malaney’s column.

4 Ibid.

5 “Number Rookies at Cardinal Tryout Camp Here Increased to 70,” Riverside Daily Press, March 2, 1937: 11. Fifty of the 70 were under Cardinals contracts.

6 Drohan.

7 Sam Greene, “Lake’s Distinction,” Detroit News, April 16, 1946.

8 Bush adds, “At the time, no specific reason was given for his bizarre preference for the minor leagues. The papers carried only the story that Lake’s home and family were in Oakland. But, in later years, Eddie talked about being glad to be near his family because Verla (who about that time would have been pregnant with Donna, the couple’s second daughter) “wasn’t feeling too well.” See the booklet by Karen Bush, Who the heck is Eddie Lake? (Michigan: Lexicon Services, 2003). See also United Press, “Cards’ Eddie Lake Wants Job on Coast,” New York World-Telegram, March 31, 1942. The PCL did pay reasonably well, and a number of West Coast players sometimes preferred playing closer to home.

9 Associated Press, “Half of Card Fielders Are Outside Fold,” Dallas Morning News, February 26, 1942: II, 5.

10 United Press, “Lake Wants To Play, Not Sit on A Bench,” San Luis Obispo Telegram Tribune, February 27, 1942: 5.

11 Drohan.

12 Ibif.

13 Roger Birtwell, “Eddie Lake Ill with Measles, Mates ‘Worry,’” Boston Globe, March 30, 1943: 10.

14 Associated Press, “As a Shortstop, Lake Is a Good Pitcher, Too,” New York World-Telegram, September 1, 1943.

15 Ed Rumill, “Lake, McBride and Lazor Pace Latest Red Sox Drive,” Christian Science Monitor, June2, 1945: 16. The “Inky” nickname derived from his aforementioned “swarthy complexion.”

16 Jack Malaney, “Eddie Lake Blisters A. L. Pitching,” Boston Post, August 2, 1945.

17 Joseph B. Kelley, Associated Press, “Johnson Big Reason Lake Is Bosox Star,” Washington Post, July 26, 1945: 10.

18 Melville Webb, “Red Sox Set New Mark for Double Plays,” Boston Globe, December 26, 1945: 10. Detroit News writer H. G. Salsinger explored the history of the double-play record in depth in an undated column found in Lake’s Hall of Fame player file.

19 Burt Whitman, “Red Sox Get York in Trade for Lake,” Boston Herald, January 4, 1946: 22. Whitman added, “Lake would be a fifth wheel here this year.”

20 Bush.

21 Undated, unsigned newspaper clipping found in Lake’s Hall of Fame player file.

22 Associated Press, “Eddie Lake May Be Sold By Detroit,” Charleston (South Carolina) News and Courier, April 3, 1948: 7.

23 United Press, “Tigers Lose Eddie Lake for Rest of Season,” New York World-Telegram, August 25, 1948.

24 United Press, “Lake Prefers PCL to Taking Cut In Pay From Tigers,” Sacramento Bee, May 7, 1951: 34.

25 Wilbur Adams, “Between the Sport Lines,” Sacramento Bee, May 21, 1951: 30. Adams quoted Gardner in his column.

26 Associated Press, “Lake Traded to Oak Club,” The Oregonian, February 24, 1952: 35.

27 McClatchy Newspapers Service, “Sacs Lose Three More, Sink 16 ½ Games Off Pace,” Sacramento Bee, June 9, 1952: 28.

28 Associated Press, “Jobless Eddie Lake Gets No Oaks Post,” Sacramento Bee, March 18, 1954: 30.

Full Name

Edward Erving Lake

Born

March 18, 1916 at Antioch, CA (USA)

Died

June 7, 1995 at Castro Valley, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.