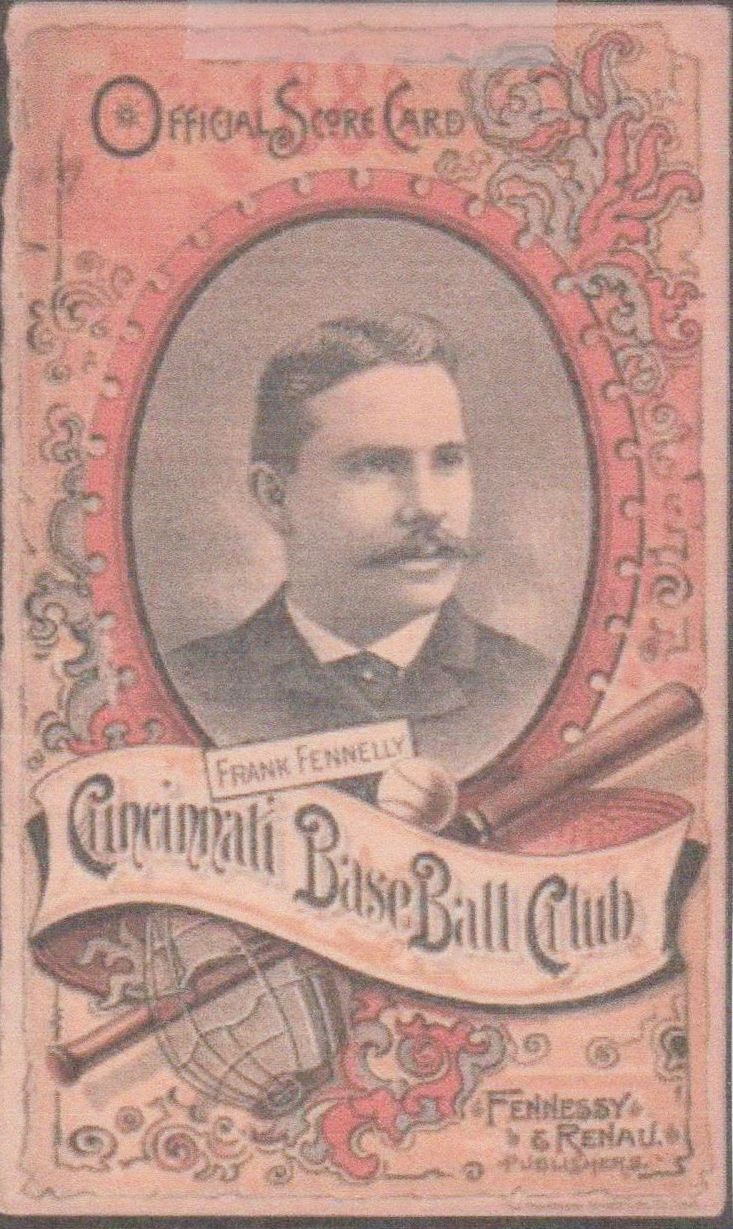

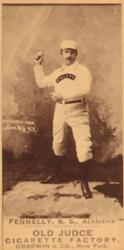

Frank Fennelly

If charted, the seven-season American Association career of shortstop Frank Fennelly would present an intriguing picture: a slightly above-average baseline with peaks of circuit-best and valleys of circuit-worst performance. When he broke into the major leagues in 1884, Fennelly had a live bat. His .311 batting average placed him in the AA’s top ten. The following season, he paced the Association in RBIs (89)1 and was third in home runs (10).

If charted, the seven-season American Association career of shortstop Frank Fennelly would present an intriguing picture: a slightly above-average baseline with peaks of circuit-best and valleys of circuit-worst performance. When he broke into the major leagues in 1884, Fennelly had a live bat. His .311 batting average placed him in the AA’s top ten. The following season, he paced the Association in RBIs (89)1 and was third in home runs (10).

Yet only four seasons later, Fennelly was unable to make reliable contact at the plate, leading the AA in strikeouts and struggling to bat .200. His fielding was much the same. Quick feet and deep defensive positioning allowed Fennelly to reach batted balls that other shortstops only waved at. This resulted in Fennelly finishing at or near the top in chances, putouts, assists, and double plays almost every season — but with errors galore, including 117 in 1886, a staggering number even in the days of the barehanded infielder. As a baserunner, Fennelly was considered one of the AA’s best, credited with as many as 74 stolen bases in a season — despite a reluctance to slide. Probably with good cause, as an awkward slide into third resulted in a career-ending injury in June 1890.

On the personal side, Fennelly displayed mostly positive traits. Sober, affable, and perceptive, he was widely admired by peers, fans, and the sporting press. Fennelly was also a natural leader, chosen as the field captain of almost every ball club he played for, from amateur nines through the majors. Nor did Frank confine his winning ways to the diamond. He enjoyed success in business and local politics as well. Fennelly was still somewhat engaged in both when a heart attack brought his life to a sudden end in August 1920. A century later, he rests among that legion of once-renowned but now-forgotten ballplayers. The ensuing paragraphs endeavor to recall the long-ago life and times of Frank Fennelly.

Francis John Fennelly was born on February 18, 1860, in Fall River, Massachusetts, then a thriving textile manufacturing center located about 50 miles south of Boston. He was the ninth of ten children2 born to teamster Thomas Fennelly (1818-1891) and his wife Catherine (née Morris, 1823-1887), both Irish-Catholic immigrants. Young Frank was educated through the eighth grade in Fall River public schools and then entered the local workforce, employed as a clerk in an older brother’s grocery store when not working as a common laborer.

Fennelly began his baseball playing days on the sandlots of Fall River, a hotbed of the 19th century game. Hometown teammates and/or rivals included future major league pitching standout Charlie Buffinton, and big league journeymen Jim Manning, Mert Hackett, Tom Gunning, and Andy Cusick. Fennelly was sturdily built (eventually 5-foot-9, 168 pounds), batted right-handed, and threw righty too, as one would expect of a shortstop. He began playing ball as a teenager with a local club called the White Stockings. In time, he advanced to the Flints, a top-notch member of the fast Fall River City League, where his teammates included catcher Gunning.3 Late in 1879, Fennelly and Gunning transferred to the rival Quequechans, teaming with hurling stalwart Buffinton to capture the Massachusetts state amateur crown.4

In March 1882, Fennelly, Buffinton, and fellow Fall River City League alumnus Jim Manning entered the professional ranks together, signing with the Philadelphia Athletics, an independent club affiliated with the League Alliance.5 By then sporting the handlebar moustache that would become a lifelong facial trademark, Fennelly was assigned to third base and, occasionally, the outfield by the A’s, but played poorly. In early May, he and Buffinton (who had only seen sparing action as an outfielder, and none as a pitcher) were released by Philadelphia.6 Thereafter, Fennelly hooked on with an independent pro club in Atlantic City, New Jersey, managed by National Association veteran Fergy Malone. On May 25, Frank debuted spectacularly for Atlantic City, going 6-for-6, with a double, a triple, and two home runs for his new club, a feat “probably never excelled in the way of batting.”7 Fennelly finished the season playing shortstop for another New Jersey team, the Camden Merritts of the minor league Interstate Association.8 Thereafter, he was placed on the Merritts’ reserve list for the coming season.9

In early 1883, the Merritts were the class of the Interstate Association. A circuit-leading record, however, was not enough to draw Camden-area fans and the club was soon in financial distress. With the Merritts log sitting at a handsome 27-8, club sponsors pulled the plug and disbanded the team in early July.10 A player dispersal draft promptly conducted at a Philadelphia hotel was attended by representatives of the National League, American Association, and other Interstate Association clubs. The rights to Fennelly and several other former Merritts were ultimately assigned to the IA’s Brooklyn Grays.11 Establishing a practice to which he would frequently resort later in his professional career, Fennelly made himself difficult to sign, demanding a $400/month contract, far in excess of the monthly $125 stipend that he had reportedly received from his erstwhile employer.12 He soon settled for less, and then set about proving his worth to Brooklyn club boss/manager George Taylor. Playing various infield positions and spearheading the attack of the pennant-winning (44-28, .611) Grays, Fennelly batted .303 and led the Interstate Association in runs scored (91), base hits (102), and home runs (6) over 75 games played, combined.13 During the ensuing post-season, Frank then got his first taste of major league play, joining the NL Providence Grays for an exhibition game tour of the Midwest.14 But in December, he was unexpectedly released by Brooklyn.15

Like a multitude of other players, Fennelly benefited from the talent scramble that attended the arrival of the self-proclaimed major league Union Association in 1884. Before the season was out, no fewer than 34 different clubs would be affiliated with one of the now three major league circuits. Given his impressive Interstate Association showing of the previous year, Fennelly was a hot commodity. But from his assorted suitors, he made a seemingly inexplicable selection: a newly-assembled American Association franchise, the Washington Statesmen. Fennelly soon had reason to regret the choice, as the Statesmen proved a sad lot. That, however, seemed far from the case on Opening Day.

On May 1, 1884, team captain Fennelly and the Washington Statesmen made a most impressive major league debut against the Brooklyn Atlantics, another new entrant in the American Association. In the first inning, Fennelly doubled off right-hander Sam Kimber, triggering a six-run uprising. By game’s end, Frank had gone 4-for-5, with four runs scored, and handled ten chances at shortstop flawlessly during a 12-0 Washington romp. Unhappily for the Statesmen, they immediately lost their next five games and were soon residing in the AA nether regions. Fennelly was about the only genuine talent on the Washington roster, and with the franchise on the brink of insolvency, his contract was dealt to the Cincinnati Reds “for a good round consideration” on August 1.16 The following day, with a 12-51 (.190) record, the Washington Statesmen abandoned play.

The change of scenery proved a tonic for Fennelly, who immediately went on an offensive tear, hitting a home run in his first game for Cincinnati. In 28 late-season games, he hit .352, with 15 extra-base hits for the 68-41 (.624) Reds. Overall in a combined 88 games played, Fennelly posted a .311 batting average, eighth-highest among American Association hitters, and placed in the circuit’s top ten in six other offensive categories.17 The only worrying sign was his 73 errors committed, second-most of any AA shortstop and a harbinger of an unhappy fielding tendency that would dog his career. After the season, Frank returned home to attend to business interests and an agreeable domestic matter: his January 1885 marriage to fellow Fall River native Julia Sullivan. The couple’s happy 35-year union would soon yield two children: Daniel (born 1886) and Catherine (1887).

During the 1885 season, Fennelly joined Long John Reilly (first base), future Hall of Famer Bid McPhee (second), and Hick Carpenter (third) to provide Cincinnati a stable infield, perhaps the Reds’ most capable of the 19th century. Frank started slowly at the plate, with concern expressed that he had “lost his gauge on the ball.”18 He soon righted matters, however, and went on to post solid offensive numbers, playing in all 112 Cincinnati games. Although his batting average dipped to .273, Fennelly compensated with impressive power numbers that included 41 extra-base hits and an AA-leading 89 RBIs. He also placed in the AA top ten in five other offensive categories.19 Defensively, he cut his errors down and posted a career-best .873 FA.20 The keystone combo of Fennelly and McPhee placed first in double plays turned for the second-place (63-49, .563) Reds.

Despite the presence of more veteran players on the Cincinnati roster, Fennelly was appointed team captain in 1886. But over the course of a campaign expanded to 138 games, his play deteriorated. Frank’s batting average fell to .249, and his other offensive numbers (extra-base hits, RBIs, OPS, slugging average, and total bases) declined perceptibly. Fennelly’s fielding stats, however, were more of a mixed bag. He led American Association shortstops in both assists (485) and double plays (54), but also in errors committed (117).21 Meanwhile, the Reds skidded to 65-73 (.474) and a non-competitive fifth-place finish.

The 1887 season was one of major league baseball’s strangest, statistically speaking. With a base on balls being counted as a base hit, batting averages soared to levels never seen before (or since), with Tip O’Neill of the St. Louis Browns being credited with a final batting average in the .490s.22 Given Fennelly’s penchant to wait out pitchers — he walked a career-high 82 times in 1887 — this one-year rule change elevated his batting average almost 100 points over where it would have been any other season: .365 vs. a normalized .266. But his other offensive numbers were also strong, with career highs in runs scored (133), RBIs (97), and stolen bases (74). An AA-leading 81 strikeouts, however, were a problem. Defensively, Fennelly posted his usual stats, both positive and negative.

Fennelly was re-elected Reds captain by his teammates that spring23 and thereafter led his club during a successful second-place (81-54. .600) campaign. Yet he was so disgruntled by season’s end that he vowed never to play in Cincinnati again. He said he would retire if not released24 — no idle threat given that Fennelly now had several income-producing ventures back home in Fall River.25 Nevertheless, Cincinnati reserved him for the 1888 season.26 Over the winter, Fennelly signed to return as Reds shortstop and team captain for “the salary limit, plus a nice bonus besides.”27 Begun with high hopes, the year proved one of personal heartache and dismal on-field performance for the Reds field leader.

Not long after he reached the Reds 1888 spring training site in New Orleans, Frank received tragic news from home. Infant daughter Katie, healthy and thriving when he left Fall River, had suddenly taken ill and died.28 Not wanting to be separated from his family after that, Frank thereafter relocated his wife and young son to Cincinnati for the season. But it did not help. His 1888 play was abysmal, particularly with the bat. It seemed like Fennelly had forgotten how to hit. Late in the season, the Cleveland Plain Dealer observed: “It looks queer to see Frank Fennelly’s name among the batting tail enders. His percentage is now but .190.”29

Fennelly became “much dissatisfied in Porkopolis” as the season wore on.30 Eventually it was rumored that he was “playing for his release.”31 If so, Cincinnati club management accommodated him. On September 24, Fennelly was sold to a league rival, the Philadelphia Athletics.32 There, an 11-for-47 mini-surge at the plate nudged Fennelly’s season-ending batting average to an even .200, albeit with an AA-leading 83 strikeouts. Meanwhile, his fielding was as schizophrenic as ever: a circuit-best 463 assists and 41 double plays counterbalanced by the most errors (100) committed by an AA shortstop.

The transfer to Philadelphia returned Fennelly to the place where he had begun his professional career some seven seasons earlier. It also briefly reunited him with hometown friend Tom Gunning.33 In spring 1889, A’s manager Billy Sharsig appointed incumbent star outfielder Harry Stovey the club’s field captain. The lately arrived Frank Fennelly assumed the post of assistant captain, much to the approval of Sporting Life, which commented: “This is undoubtedly the best selection that could have been made and will give great satisfaction to the club. Both [Stovey and Fennelly] are great players and competent to fill the position.”34

The observation proved half-right. Stovey went on to have a banner season, leading American Association batters in runs scored (152), home runs (19), RBIs (119), slugging average (.525), and total bases (292). Fennelly, however, got off so slowly that by late May he had to be benched “for weak hitting.”35 There was also a disturbing report that the previously abstemious Fennelly was occasionally joining Stovey, Curt Welch, and other hard-drinking teammates on their evening tours of Philadelphia’s saloons.36 Nevertheless, Frank’s play began to pick up during the summer; he finished the season with a respectable .257 batting average and 64 RBIs. And his fielding stats stayed about the same as the year before, but with fewer errors (93) in more games played (a career-high 138).

Despite the decent comeback season, Fennelly was unhappy in Philadelphia. As always, however, his grievances could be redressed by “a little more money next year.”37 Later, it was reported that in addition to a salary raise, Frank wanted “a contract that will run for more than one year.”38 Club management opted for a different solution: sale of the Fennelly contract to the Brooklyn Gladiators, a newly-organized American Association entry.39 Once Fennelly was in the fold, club boss Jim Kennedy appointed the veteran shortstop the Gladiators’ field captain.40 The acquisition pleased the local baseball press. The New York Herald informed readers that “Frank Fennelly is one of the best shortstops playing ball today and a good batter.”41 But the 1890 season would prove an extremely trying one for him, as the Brooklyn Gladiators were a hapless club.

With the Gladiators floundering near the bottom of AA standings in early June, Fennelly swallowed his pride and moved over to third base so that 41-year-old veteran Candy Nelson could be tried at short. The experiment lasted seven games. By June 13, the Gladiators’ log stood at an unsightly 12-26, and captain Fennelly’s patience was wearing thin. Normally genial, Fennelly was so incensed by criticism published in the Philadelphia Press that he “publicly abused” a Press reporter while still in Gladiators uniform, a rules infraction that led to a formal charge being lodged against Fennelly with the Association office.42 An intervening event soon rendered disciplinary proceedings moot: the end of Frank Fennelly’s major league career.

During the second game of a doubleheader loss to Philadelphia on June 18, an awkward slide into third base resulted in a leg injury so severe that Fennelly was deemed through for the season.43 The Brooklyn club was teetering on the brink of financial collapse — indeed, the 26-73-1 Gladiators would disband in late August. Thus, carrying their laid-up captain on the roster was a luxury that the club could not afford. “The Brooklyn club regretted to part with him, but no other course [besides Fennelly’s unconditional release] presented itself,” maintained the Boston Herald.44 The big league career of our subject was now over.

During the second game of a doubleheader loss to Philadelphia on June 18, an awkward slide into third base resulted in a leg injury so severe that Fennelly was deemed through for the season.43 The Brooklyn club was teetering on the brink of financial collapse — indeed, the 26-73-1 Gladiators would disband in late August. Thus, carrying their laid-up captain on the roster was a luxury that the club could not afford. “The Brooklyn club regretted to part with him, but no other course [besides Fennelly’s unconditional release] presented itself,” maintained the Boston Herald.44 The big league career of our subject was now over.

While not quite a star, Frank Fennelly had been a first-rate player during his seven-season major league stay. Over 786 games played, his chronically up-and-down batting average settled at a respectable .257, with good power numbers, particularly for a 19th century shortstop: 34 home runs and 408 RBIs. Indeed, he had been the American Association leader in two single-season offensive categories — RBIs in 1885 and being hit by pitch, 18 times in 1886. On the minus side, Fennelly had led AA batsmen in strikeouts twice. His fielding stats were uneven as well. Frank led AA shortstops in assists twice and double plays three times, but was also a three-time leader in errors committed.

Following his release, Fennelly (then 30) returned to Fall River. In time, his business interests there expanded into the operation of a local saloon.45 But after two years on the sidelines, Frank returned to the game, joining the Fall River Indians of the minor New England League. Serving as both team captain and everyday shortstop, he played all but one game on the Fall River schedule and batted a solid .272, with 95 runs scored and 31 stolen bases. Fennelly was given much of the credit for the Indians’ first-place (60-30) finish, but strife developed between him and non-playing manager Mike McDermott as the season progressed. During the off-season, Fennelly partisans attempted to oust McDermott as Fall River manager, but failed. This led Fennelly to leave his hometown club.46 At first, it was rumored that he was trying to start up a club in nearby Taunton, Massachusetts.47 In late February 1894, however, Fennelly signed to captain and play short for an NEL rival club in Portland, Maine.48 But his time in Portland was brief. Frank was released in mid-May,49 and by July he was umpiring games in the New England League, instead.50

After the 1894 season, Fennelly and friends took another stab at supplanting Mike McDermott as Fall River manager. And when the attempt again failed, he began to make noise about entering his own Fall River ball club in a rival circuit, the proposed Eastern Association.51 Fennelly hastened to add, however, that while he would take an active part in formation of the new Fall River nine, he would not serve as its manager. Fennelly had just taken on a new job as a salesman for the Cudahy Beef Company that required his full attention.52 But nothing ever came of it; both the fledgling Fall River club and the Eastern Association were stillborn. And with that, Frank Fennelly withdrew from Organized Baseball — at least for a time.

Other endeavors promptly filled the void for the energetic Fennelly. In addition to his job with Cudahy, Frank became a Fall River wine merchant. By 1900, he was also the local tax collector.53 During the summer of 1902, he returned to umpiring, this time in the minor Connecticut League.54 Always a popular figure in his hometown, Fennelly turned his hand to local politics and was elected to a one-year term as Massachusetts state representative for the 10th (Bristol County) District in 1905. A Democrat, he was thereafter re-elected the next three years running. During his time in the state house, Representative Fennelly’s duties included committee oversight of street railways, roads and bridges, and prisons.55 He also introduced the legislation needed to fund construction of a contagious diseases hospital in Fall River.56 Upon return to private life, he worked for an insurance company. He also remained marginally connected to local politics, serving as an enumerator for the 1920 US Census.

While parking his car in the garage of his Fall River home on the evening of October 5, 1920, a seemingly hale and hearty Fennelly fell victim to a fatal heart attack. He was 60. Following a viewing at the Fennelly family residence, his remains were transported to Sacred Heart Church for a High Requiem Funeral Mass. Among the pallbearers was his former teammate and lifelong friend, Dr. Thomas F. Gunning, by then the Bristol County medical examiner.57 Interment was at nearby St. Patrick’s Cemetery, Fall River. Survivors included widow Julia and son Dr. Daniel Fennelly. Admired in his time but forgotten in ours, Frank Fennelly’s fine major league playing career was but one aspect of a life well-lived.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources

Sources for the biographical information provided herein include Fennelly profiles published in the New York Clipper, March 23, 1889, Baseball’s First Stars, Frederick Ivor-Campbell, Robert L. Tiemann, and Mark Rucker, eds. (SABR: Cleveland, 1996), and Major League Player Profiles, 1871-1900, Vol. I, David Nemec, ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011); US Census and other government records accessed via Ancestry.com; and certain of the newspaper articles cited below, particularly the lengthy Fennelly obituary published in the Fall River (Massachusetts) Globe, August 5, 1920. Unless otherwise noted, stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

Notes

1 As retroactively calculated by modern day researchers. The RBI did not become an official major league statistic until 1920.

2 Frank’s siblings were a first name-unknown oldest brother (born 1840), James (1842), Michael (1845), Thomas (1847), Mary Ann (1849), Stephen (1854), Charles (1856), John (1858), and Alvin (1864).

3 Per “Was Wonderful Ball Player,” Fall River (Massachusetts) Globe, August 5, 1920: 13.

4 Per local news clippings furnished the writer by Fall River historian and early baseball expert Philip T. Silvia Jr.

5 As reported in “In and Out-Door Sports,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 14, 1882: 5. For more on the Philadelphia Athletics and its arrangement with the League Alliance, see Robert L. Warrington, “Philadelphia in the 1882 League Alliance,” Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 48, No. 2 (Fall 2019), 105-124.

6 As noted in “Base Ball Yesterday,” New Haven (Connecticut) Register, May 6, 1882: 2; “Sporting Sparks,” (Springfield) Illinois State Journal, May 7, 1882: 2.

7 According to “Diamond Dust,” Cleveland Leader, June 6, 1882: 5. See also, Charles F. Faber, Major League Careers Cut Short: Leading Players Gone by 30 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2010), 114.

8 As reflected in late-1882 season box scores published in the Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Patriot, Wilmington (Delaware) Gazette, and elsewhere. The Camden club was named for New Jersey State Senator Albert Merritt, its principal financial backer.

9 Per “Base Ball,” Harrisburg Patriot, November 27, 1882: 4, citing the Philadelphia Record.

10 See “Senator Merritt,” Lancaster (Pennsylvania) Intelligencer, July 20, 1883: 3; “The Disbanded Merritts,” Harrisburg Patriot, July 23, 1883: 1.

11 As reported in the Lancaster Intelligencer, Wilmington Gazette, and elsewhere, July 24, 1883.

12 Per a widely distributed wire service dispatch. See e.g., “The National Game,” Abbeville (South Carolina) Press & Banner, August 15, 1883: 1.

13 Per Interstate Association stats published in The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds. (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 2d ed. 1997), 108.

14 See “The Record: Results of Exhibition Games Played at Various Points,” Sporting Life, October 22, 1883: 4, and accompanying box scores. The personal highlight of Fennelly’s audition with Providence occurred on October 12 when he hit an eighth-inning triple and scored the only run in a 1-0 Grays victory over the American Association Cincinnati Reds.

15 As reported in “Base-Ball Notes,” New York Times, December 21, 1883: 2. Fennelly’s release followed Brooklyn’s acquisition of Jack Warner to play third base.

16 See “A Short Stop,” Cincinnati Commercial Gazette, August 2, 1884: 3. The purchase price was likely $1,000.

17 Including present-day metrics, Fennelly’s top-ten stats included a .367 OBP (4th), .480 SLG (4th), .847 OPS (4th), 41 extra-base hits (7th), 22 doubles (9th), and 31 walks (9th).

18 See “Notes,” Cincinnati Commercial-Gazette, April 21, 1885: 3.

19 Fennelly ranked second in triples (17), fifth in walks (38), sixth in slugging percentage (.445) and total bases (202), and seventh in OPS (.738).

20 Fennelly’s career-best .873 FA was about middle-of-the-pack for AA shortstops in 1885.

21 The noticeably deep position that he took at short allowed Fennelly to reach batted balls that would otherwise have gone into the outfield., as noted the next year by the Washington Daily Critic, August 22, 1887: 4. And the more batted balls that he got to, the more Fennelly exposed his fielding record to the harsh official scoring judgments that characterized the 1880s. That said, Fennelly’s .849 FA ranked next-to-last of the AA shortstops measured. See 1886 defensive stats published in “The American Association,” The Sporting News, November 20, 1886: 2.

22 To this day, O’Neill’s final numbers for the 1887 remain in dispute. For more, see Dennis Thiessen, Tip O’Neill and the St. Louis Browns of 1887 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2019).

23 See “World of Sport,” Cleveland Leader, April 3, 1887: 11: “Manager Gus Schmelz allowed Cincinnati players to choose their own captain. They selected Frank Fennelly and all were satisfied.”

24 See “Base Ball Notes,” New York Sun, October 2, 1887: 11. The cause of Fennelly’s discontent was not specified in the article but same likely centered on his compensation by Cincinnati management, as Fennelly was often dissatisfied about his wages during his baseball career.

25 Including a large grocery store, Fennelly’s hometown business interests “pay him twice his baseball salary,” reported Sporting Life, January 11, 1888: 1.

26 See “Reserved Ball Players,” Chicago Inter-Ocean, October 29, 1887: 2.

27 Per “Fennelly Signs with Cincinnati,” Sporting Life, January 4, 1888: 1, and “One of Cincinnati’s Two Grocerymen,” Sporting Life, January 11, 1888: 1. See also, “The Diamond,” Boston Herald, January 3, 1888: 7.

28 Per Ren Mulford Jr., “The Reds Trip,” Sporting Life, February 22, 1888: 3.

29 “Base Ball Notes,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 26, 1888: 3. It has been theorized that a change in the playing rules precipitated Fennelly’s batting decline. A notorious low-ball hitter, he supposedly proved unable to cope when the rule change discontinued the batter’s right to call for a high (above the waist) or low (below the waist) strike be pitched to him. See e.g., “Frank Fennelly,” Major League Player Profile, 1871-1900, Vol. 1, David Nemec, ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 455. But the uniform strike zone had been adopted a year earlier, and the solid batting stats posted by Fennelly in 1887 contradict the notion that he was dramatically handicapped by the rule change.

30 “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, September 26, 1888: 4.

31 “Sprays of Sport,” Denver News, September 16, 1888: 3.

32 In return, Cincinnati received $1,000, per Retrosheet.

33 Regrettably for the two, the reunion would not last long. Philadelphia released Gunning in June 1889, bringing his baseball career to an end. Tom subsequently completed his medical studies at the University of Pennsylvania and then returned to Fall River to establish his practice.

34 “Philadelphia Pointers,” Sporting Life, March 27, 1889: 4. See also, “Sports of the Spring,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 21, 1889: 6, and “The Sporting World,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 24, 1889: 2.

35 Per “Baseball Notes,” Erie (Pennsylvania) Times, May 25, 1889: 1.

36 According to an undated June 1889 report in the Philadelphia Times. The preceding year, Cincinnati club boss Aaron Stern had awarded Fennelly a $500 contract clause bonus for refraining from alcohol use during the entire 1888 season. See “The Sporting World,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 1, 1888: 5.

37 Per “A Little Trouble in the Athletic Camp,” Sporting Life, November 6, 1889: 7.

38 Per “Hits from the Bat,” Boston Herald, January 4, 1890: 10.

39 As reported in “Short Stops,” Boston Herald, February 9, 1890: 3; “Brooklyn Budget,” Sporting Life, February 12, 1890: 2, and elsewhere.

40 See “Gossip of the Game,” Kalamazoo (Michigan) Gazette, February 23, 1890: 8; “The Association,” Wichita (Kansas) Eagle, April 1, 1890: 8.

41 “Among the Ball Men,” New York Herald, February 9, 1890: 18.

42 As reported in “Notes and Gossip,” Sporting Life, June 21, 1890: 4.

43 See “Ramsey in Disgrace Again,” Baltimore Sun, July 7, 1890: 1; “Notes of the Diamond Field,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 10, 1890: 3; “Notes and Gossip,” Sporting Life, July 12, 1890: 4.

44 “Hits and Tips,” Boston Herald, July 11, 1890: 4. Brooklyn’s release of Fennelly was also reported in “Base Ball Notes,” New York Sun, July 8, 1890: 4, and the news articles cited in endnote 43.

45 Per “Happy Birthday, Frank Fennelly!” Mighty Casey Baseball, posted on-line February 18, 2019.

46 As reported by Boston sportswriter Jacob C. Morse in “Hub Happenings,” Sporting Life, January 20, 1894: 5, and February 10, 1894: 5. It was later revealed that McDermott had greased the skids for Fennelly’s departure by cutting his salary while every other Fall River player received an increase in pay for the 1894 season. See “Fall River Facts,” Sporting Life, December 8, 1894: 3.

47 Ibid.

48 See Edwin Phillips, “Portland Points,” Sporting Life, February 24, 1894: 4; “General Sports Notes,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 14, 1894: 4.

49 As reported in “Fall River Nine for ’94,” Portland (Maine) Herald, May 14, 1894: 8.

50 Fennelly was appointed an NEL umpire by league president Tim Murnane, a longtime friend.

51 See “Fall River May Have a Rival Club,” Boston Herald, October 7, 1894: 4.

52 “Fall River Facts,” Sporting Life, December 8, 1894: 3.

53 The Fennelly occupation listed in the 1900 US Census.

54 Per “News Notes,” Sporting Life, May 31, 1902: 20.

55 Per “Who’s Who in State Politics,” 1908, and Fennelly’s obituary “Was Wonderful Ball Player,” Fall River Globe, October 5, 1920: 13.

56 As noted in the Fennelly obituary, above.

57 As related in “Funerals: Francis J. Fennelly,” Fall River Globe, October 7, 1920: 12.

Full Name

Francis John Fennelly

Born

February 18, 1860 at Fall River, MA (USA)

Died

August 4, 1920 at Fall River, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.