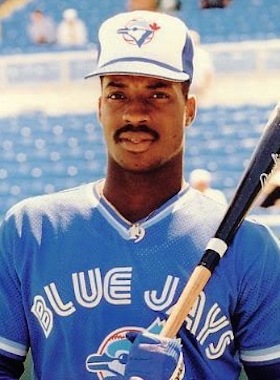

Fred McGriff

“I was blessed,” said Fred McGriff, reflecting on a decorated career that landed him in the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2022.1

McGriff signed his first pro contract when he was 17. During his 19-year major-league career, McGriff was a five-time All-Star, won the Silver Slugger award three times, and hit 30 or more home runs 10 times. In 1995 he led the Braves to their first world championship in Atlanta, and in 1998 brought professionalism and credibility to one of the worst teams ever, the expansion Tampa Bay Devil Rays.

In 1992, McGriff became the first player to lead both the American and National Leagues in home runs since the nineteenth century. He was also the first player to hit 30 or more home runs for five different teams. ESPN’s Chris Berman gave Fred McGriff one of the most memorable baseball nicknames of the 1990s: “Crime Dog,” after the cartoon public service announcement dog McGruff.

McGriff was born in Tampa, Florida, on October 31, 1963, the youngest son of Eliza and Earl McGriff. He had two sisters, Sandra and Terri, and two brothers, Michael and Dexter. Earl McGriff told Sports Illustrated, “We let our children produce at their own speed. We didn’t push them. We didn’t hold them back.”2

Fred McGriff grew up four blocks from Al Lopez Field, the longtime spring training home of the Cincinnati Reds, which gave him a lot of exposure to major-league baseball at an early age. “I can’t remember going to my first game,” he once said. “I mean, I was always at a

baseball game. I lived at ballgames. I always loved the game.”3

McGriff started playing organized ball in the West Tampa Little League. At Jefferson High School he played for coach Emeterio “Pop” Cuesta. In his long career, Cuesta also coached major leaguers Luis Gonzalez and Tino Martinez. Cuesta cut McGriff from the team during his sophomore year. Being cut from the team must have hurt McGriff, but perhaps it also motivated him, since he got back on the high school team and went on to a successful major-league career.

In June 2011 at a ceremony honoring Cuesta’s 40th anniversary of coaching baseball, McGriff asked him why. Cuesta responded to the audience, “First of all, this is not the Fred McGriff here as a sophomore. The Fred McGriff that was here was about 5-foot-6, 5-foot-7 with glasses. I told him to hit the ball, I mean, he hit it, but it wouldn’t go very far.”4

McGriff grew very quickly into a solid prospect during his junior year of high school. In 1981, after his senior year, the New York Yankees selected him in the ninth round of the amateur draft. McGriff had been offered several college scholarships, but decided to sign with the Yankees.

In a brief stint in the Gulf Coast League in 1981, McGriff hit just .148, but next season raised his average to .272 in 62 games. He led the league with 9 home runs and 41 RBIs in 62 games. After the season the Yankees traded McGriff, outfielder Dave Collins, pitcher Mike Morgan, and cash to Toronto for pitcher Dale Murray and infielder Tom Dodd (Rob Neyer included this trade in his book, Rob Neyer’s Big Book of Baseball Blunders, as one of the worst trades the Yankees ever made.).5

While McGriff was in the minors he visited a coach and swing doctor in Orlando, Tom Emanski. McGriff found Emanski’s coaching helpful, and the relationship he developed with Emanski would also become very lucrative for McGriff.

The Blue Jays sent their new acquisition to Kinston in the Carolina League. In 1984 McGriff was named the number-two prospect in the Blue Jays’ system by Baseball America. After moving up through Toronto’s minor-league system, McGriff was called to the big club from Syracuse in mid-May of 1986. He made his major-league debut, at the age of 22, on May 17, 1986, against the Cleveland Indians as a defensive replacement for Willie Upshaw. The next day McGriff started his first game, as the designated hitter and lined the first pitch he saw into left field for a single. He got into one more game before the Jays returned him to Syracuse for the rest of the season, where he hit .259 with 19 home runs and 74 RBIs.

The next season McGriff made the Blue Jays roster as a DH/first baseman, platooning sometimes with Cecil Fielder. McGriff hit .247 with 20 home runs in 107 games. He hit his first major-league home run on April 17 against the Boston Red Sox’ Bob Stanley in Toronto – a three-run shot with two out in the bottom of the fifth that gave the Blue Jays a 7-5 lead in a game they won 10-5

Tom Emanski called McGriff during the season to ask a favor. As McGriff told the New York Times, “I’m in the big leagues and we’re playing in Chicago. After the game he picks me up right outside the stadium and we go to a Little League park. He just gives me this shirt and this hat and says put them on. He had his own little video camera so he shoots the video. At the time I was just like, OK give me one percent. I didn’t know it was going to turn into anything.”6

The video, Tom Emanski’s Defensive Drills, became one of the best-selling baseball instructional videos of the 1990s, thanks to an ad campaign on ESPN featuring McGriff’s endorsement. McGriff said he was kidded in every locker room whenever that commercial aired on ESPN. “I’m sure he made millions,” McGriff added, “but the thing is, he did a great job and he did help me get to the big leagues. He helped me make a great living also.”7 McGriff’s percentage added up to a great deal of money over the years.

In 1988 the Blue Jays made McGriff their regular first baseman. He played 154 games and hit .282 with 34 home runs (second in the AL to Jose Canseco) and 82 RBIs, beginning a streak of seven straight years hitting 30 or more homers.

In 1989 the Blue Jays moved to the Skydome, and McGriff blossomed into one of the most dangerous sluggers in the majors. On June 5 he celebrated the first game in the new park with a home run. McGriff batted .269, led the AL with 36 home runs, and won his first Silver Slugger award. Teammate Lloyd Moseby said of McGriff, “You know that highlight reel that shows the Willie Mays catch and then switches to the fan who grabs his head with his hands in amazement? Fred McGriff does that to you when he hits a home run.”8 The Blue Jays won the AL East, but lost in the ALCS to the Oakland A’s. McGriff hit a disappointing 3-for-21 in the series.

McGriff suffered through a slump early in 1990, but managed to finish strongly, batting .300 with 35 home runs and 88 RBIs. Then, after the season, the Blue Jays made a blockbuster trade with the San Diego Padres, sending the 26-year-old McGriff and shortstop Tony Fernandez, to the San Diego Padres for catcher Roberto Alomar and outfielder Joe Carter. The trade worked out well for the Blue Jays, who won the AL East in 1991 and back-to-back World Series in 1992 and 1993. In 1991, McGriff hit .278 with 31 home runs and 106 RBIs as the Padres finished third in the NL West.

McGriff started 1992 on fire, hitting homers in four of his first five games, including a grand slam. In July he homered in four consecutive games, was voted onto the NL All-Star team, and went 2-for-3 in the game. He finished the season with a .286 batting average, led the league. with 35 home runs and drove in 104 runs. That earned him a second Silver Slugger award, and he finished sixth in MVP voting, his best showing so far. McGriff became the first player to lead two different major leagues in home runs since Harry Stovey (National League and American Association) in the 19th century.

McGriff earned just over $4 million in 1992 and signed a 1993 contract for $4.2 million. He got off to a terrible start, batting just .190 in April. Although he improved to .275 by July, the Padres were going nowhere, and the front office was ordered to cut payroll. The Atlanta Braves needed a hard-hitting first baseman, and on July 18 relieved the Padres of McGriff’s services and salary for three prospects: Vince Moore, Donnie Elliot, and Melvin Nieves.

When McGriff came to Atlanta the Braves were in second place in the NL West, nine games behind the San Francisco Giants. McGriff joined the Braves in Atlanta for a game against the Cardinals on July 20. Before the game, a fire broke out in the press box. No one was hurt, the fire was put out, and the game started. Coincidentally or not, McGriff’s presence appeared to ignite the Braves. They were behind 5-0 entering the bottom of the sixth. Jeff Blauser hit a three-run homer and Ron Gant singled. McGriff then launched a two-run homer that tied the game. The Braves went on to win 8-5.

Years later, McGriff told a reporter how he felt about the trade and his first game with Atlanta. He said, “The Padres were having a fire sale, so it didn’t surprise me … my ribs were really bothering me when I was traded, and the Braves let me go home to Tampa for a day or two to rest them. Then my plan was to come up for the first game in the St. Louis series, but I intentionally left my house in Tampa at noon because I knew I would get up to the game right before it started and would get another night off to rest my ribs. But then came the fire, I was in the lineup and the game started after 9. I spent most of my time before the game in the training room with the trainer working on my ribs. Then I went out and hit that homer. It was crazy.’’9

In the 68 games McGriff played from July 20 to the end of the season, the Braves went 51-17. McGriff hit 19 homers, drove in 55 runs, and had a 1.004 OPS. In his book The Time of Bobby Cox, author Lang Whitaker wrote, “With McGriff on the team, the Braves were definitely combustible. Fred McGriff got the Braves red hot.”10

The Braves passed the Giants and won the West Division championship by one game with a record of 104-58. For the season, McGriff finished with a .291 batting average, 37 home runs, and 101 RBIs. Although the Braves lost the NLCS to the Philadelphia Phillies in six games, McGriff stayed hot, batting .435 for the series with one home run and four RBIs. He won another

Silver Slugger award and finished fourth in the MVP voting – his career high.

Teammate Ron Gant gave McGriff a great deal of credit for the Braves’ surge, telling a sportswriter, “He just makes everyone else a better hitter. I hit in front of him. It wasn’t that the pitchers were throwing me different pitches. They were throwing me the same pitches, but I was just more of an aggressive hitter with him hitting behind me. He just makes everyone else better.”11

McGriff appeared to be on his way to a career year in 1994, batting .310 with 23 home runs and 63 RBIs at the All-Star break. In the All-Star Game his two-run pinch-hit homer in the ninth inning off Lee Smith tied the score, and he was named the game’s MVP after the National League won in the 10th. Of the home run, he said, “It was a fastball away. He blew the second pitch by me. I was thinking, let it go, be aggressive, take your whacks. If you don’t get him, get ready for Thursday and play the Marlins.”12

A month after the All Star-Game the season ended for everyone. Players responded to the owners’ efforts to unilaterally enforce new policies that would lead to a salary cap by striking on August 12, 1994. The strike led to the first World Series cancellation in 90 years and delayed the start of the 1995 season. McGriff finished 1994 with a full season’s work: 34 homers, 94 RBIs, and a .318 batting average in only 113 games. Since McGriff finished his career with 493 home runs, it’s tempting to think that had the season continued, McGriff could have hit at least eight more homers. Perhaps getting over the 500-home run mark would have made a difference in McGriff’s Hall of Fame support.

When the 1995 season opened on April 26, McGriff showed his long hiatus hadn’t cooled down his bat, as he went 4-for-5 with two home runs against the San Francisco Giants. The Braves had high expectations for success in 1995. McGriff said, “It was win or bust that year.”13 McGriff played every game that season, made his third All-Star Game, and helped the Braves win the NL East crown with a .280 batting average, 27 home runs, and 93 RBIs.

The Braves beat the Colorado Rockies in the NLDS four games to one and swept the Cincinnati Reds in the NLCS to face the Cleveland Indians in the World Series. McGriff batted a sizzling .438 in the NLCS to spark the team. In Game One of the World Series, he homered off Orel Hershiser in his first World Series at-bat. McGriff batted .261 for the Series. He hit another home run in Game Three. He also had two doubles and a .609 slugging average as the Braves defeated Cleveland in six games for their first Series victory, and the only Series win for a Bobby Cox-managed team.

McGriff had another solid year in 1996 to lead the Braves to another division championship. On May 19, he reached the 300-lifetime homer mark. He finished the season with a .295 batting average, 28 homers, and 107 RBIs. The Braves won the pennant but lost to the Yankees in the World Series.

The Braves reached the postseason again in 1997, even though McGriff’s home runs declined to 22, but with 97 RBIs. He didn’t make the All-Star team, and the Braves lost to the Florida Marlins in the NLCS. Two new teams, the Tampa Bay Devil Rays and the Arizona Diamondbacks, were admitted to the major leagues for 1998. On the day of the expansion draft, the Braves sold McGriff to the Devil Rays, sending the Crime Dog back to his home town. Ever the gracious professional, McGriff simply said about moving from one of the best teams in baseball to an expansion team, “Going back and getting to play in front of my parents in our hometown was really special.’’14

On April 1, 1998, McGriff drove in four runs to spark the Devil Rays to the franchise’s first win, over the Tigers. He had a poor year for the Rays by his standards, hitting .284 with just 19 home runs and 81 RBIs. (He did lead the team in those categories.) McGriff rebounded in 1999, hitting 32 homers, driving in 104 runs, and batting .310.

In 2000 the Devil Rays signed some high-profile free agents, including Vinny Castilla and Greg Vaughn, to join McGriff and Jose Canseco. They dubbed their new lineup “The Hit Show,” and raised expectations high for the 2000 season. But only McGriff and Vaughn had decent seasons. On June 2 McGriff hit a home run off the New York Mets’ Glendon Rusch that made him the 31st major leaguer to reach 400 homers. McGriff also represented the Devil Rays in the All-Star game. He finished the season with 27 home runs, 106 RBIs, and a batting average of .277. On September 23 McGriff became the second player (along with Frank Robinson) to hit 200 home runs in both leagues when he homered off Roy Halladay of the Blue Jays.

McGriff started slowly in 2001 but soon heated up and was hitting over .300 for the Devil Rays when the team traded him to the Cubs. McGriff, 37, was being paid $6.5 million. When the deal was originally made on July 8, McGriff invoked his no-trade clause. Later in the month he accepted the deal and went to Chicago.

The Cubs wanted a strong left-handed bat to hit behind Sammy Sosa, on his way to 64 home runs. In 49 games with the Cubs, McGriff hit 12 homers. For the full season he hit 31, with102 RBIs and a .306 batting average.

The Cubs picked up their option on McGriff for 2002. Taking advantage of the hitter-friendly Wrigley Field, McGriff hit 30 homers drove in 103 runs with a .273 batting average. This was McGriff’s 10th 30-homer season, and he became the first player to hit 30 or more homers with five different teams. Despite McGriff’s hitting, the Cubs finished fifth in the NL Central Division, and the team opted not to re-sign the 39-year-old, making him a free agent for the first time in his career.

The Los Angeles Dodgers signed McGriff for the 2003 season for $3.75 million, about half his Cubs salary. They hoped McGriff could give them the same steady power in the middle of the order and perhaps attract some fans who wanted to see him break the 500-home-run barrier.

For the first time in his career, McGriff’s body broke down. He missed extended periods with knee, hip, and groin injuries. When he was playing, the injuries hurt his game. He played in 86 games and ended up with 13 homers and 41 RBIs. Worse, he batted only .249. Still, McGriff ended the season only nine home runs away from 500, and with an offseason to rehab many thought he would make it.

The Dodgers did not re-sign McGriff for 2004. In March the 40-year-old signed with the Devil Rays and started the season with the Triple-A Durham Bulls. On May 28 he joined the Devil Rays, who were noted for bringing in older players close to achieving milestones to improve attendance. McGriff hit a home run on May 31 to spark a 7-5 win over the Minnesota Twins. That started a small hot streak, and by June 17 he was batting .269. He hit his second home run that day. That was the high point – McGriff slumped to a .181 average by July 15, and didn’t hit another home run.

That July 15 game was McGriff’s last. The Devil Rays released him on July 28. He officially retired during spring training 2005, seven home runs shy of 500. His 493 home runs tied him with Lou Gehrig. He also ended his career with 2,490 hits, 1,550 RBIs and 1,349 runs scored. He batted .284 with a .377 on-base percentage, and an .886 OPS (on-base percentage plus slugging average). McGriff hit even better in postseason play. In 50 games he batted .303 with 10 home runs and 37 RBIs, with a .917 OPS. He hit four home runs in 12 World Series games.

McGriff became eligible for election to the Hall of Fame in 2010 and received 21.5 percent of the vote. Many writers thought McGriff would eventually be voted in, but he never came close to receiving the required 75% of votes. In 2019, his last year of eligibility on the baseball writers’ ballot, McGriff received 39.8% of the vote – good for 10th place, but not for the Hall of Fame. Some suggested McGriff’s chances were hurt by playing for five different teams in his career, some say it was because he didn’t hit 500 home runs. Hall of Famer Chipper Jones, his teammate on the Braves, thought McGriff should get elected. “There was nobody I enjoyed hitting in front of more than Fred McGriff.”15

In December 2022, McGriff was unanimously elected to the Hall of Fame by the Contemporary Era Committee, which included his former Braves teammate Greg Maddux, former Blue Jays teammate Kenny Williams, and former Blue Jays executive Paul Beeston.

Baseball made McGriff a wealthy man. He earned over $65 million in salary during his playing career, which was supplemented by his royalty percentage from the Tom Emanski video. After his playing career was over, McGriff consulted and coached for some of his former teams, including the Blue Jays. He spent 2007 through 2010 as a consultant for the Rays (formerly the Devil Rays), as the team moved from the AL East depths to a World Series appearance and regular contention for the division title. He also hosted a sports radio talk show in Tampa. In 2015, the 20th anniversary of the Braves’ World Series victory, the Braves signed McGriff to serve as a spring-training instructor and scout. As of 2019, McGriff still worked for the Braves and sold his house in Tampa.

Last revised: December 4, 2022

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseballamerica.com,

baseballhall.org, Baseball-reference.com, draysbay.com, MLB.com, Orlando Sentinel, Retrosheet.org, Sports Illustrated, and SABR.org.

Notes

1 David O’Brien, “McGriff Q & A Part 2,” Atlanta Journal Constitution, March 9, 2018. https://www.ajc.com/sports/baseball/mcgriff-part-hall-fame-snub-and-advice-for-prospects/kWtUEZUP9eGY6wD3bxnv3J

2 Ralph Wiley, “Give Us a Smile, Hit It a Mile – Fred McGriff,” Sports Illustrated, May 8, 1989. https://www.si.com/vault/1989/05/08/119855/give-us-a-smile-hit-it-a-mile-fred-mcgriff-of-the-toronto-blue-jays-is-mr-nice-guy—-until-he-punishes-opposing-pitchers-with-his-tape-measure-home-runs

3 Ibid.

4 Eddie Daniels, “Jefferson’s Pop Cuesta Honored for 40 Years of Coaching,” Tampa Tribune, June 4, 2011. http://ttt-tbdev.newscyclecloud.com/sports/preps/jefferson-dragons/baseball-jeffersons-pop-cuesta-honored-for–years-of-coaching-235095

5 Rob Neyer, Rob Neyer’s Big Book of Baseball Blunders (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006), 209-210.

6 Tyler Kepner, “Deciphering Hall Ballot Without Superstar,” New York Times, January 5, 2010: B15.

7 Kepner.

8 Wiley.

9 O’Brien.

10 Lang Whitaker, In the Time of Bobby Cox (New York: Scribner, 2011), 111-112.

11 Claire Smith, “McGriff and Turnaround are Same Word to the Braves,” New York Times, October 5, 1993: B16

12 Ibid.

13 Wiley.

14 O’Brien.

15 Marc Topkin, “Know Who Thinks Fred McGriff Deserves to Be in the Hall of Fame? New Member Chipper Jones,” Tampa Bay Times, January 25, 2019. https://www.tampabay.com/blogs/rays/2018/01/25/know-who-thinks-fred-mcgriff-deserves-to-be-in-the-hall-of-fame-new-member-chipper-jones/

Full Name

Frederick Stanley McGriff

Born

October 31, 1963 at Tampa, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.