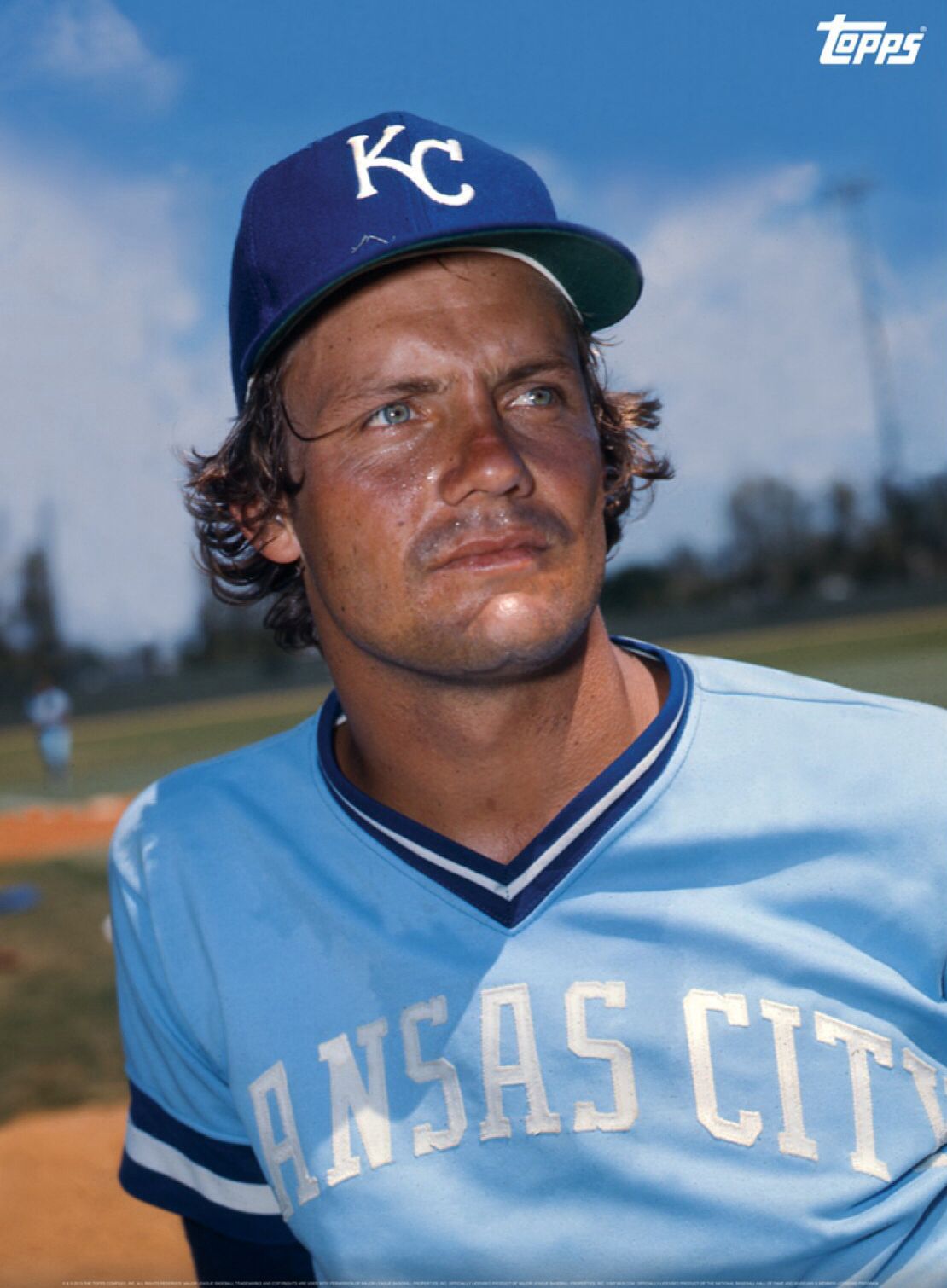

George Brett

Few players have been as synonymous with a team as George Brett and the Kansas City Royals. Yet the amiable, self-deprecating, and sometimes volatile Brett never viewed himself as being greater than the team he loved. A throwback to an earlier time, Brett favored pine tar over batting gloves, chewing tobacco over bubble gum, and cold beer over weightlifting. As the Royals reached the half-century mark, Brett remained the only player to represent the team in baseball’s Hall of Fame.

Few players have been as synonymous with a team as George Brett and the Kansas City Royals. Yet the amiable, self-deprecating, and sometimes volatile Brett never viewed himself as being greater than the team he loved. A throwback to an earlier time, Brett favored pine tar over batting gloves, chewing tobacco over bubble gum, and cold beer over weightlifting. As the Royals reached the half-century mark, Brett remained the only player to represent the team in baseball’s Hall of Fame.

George is the youngest of four brothers. All four boys wound up playing baseball professionally. John, the oldest, got as far as Class-A ball in 1968, playing for the Waterloo (Iowa) Hawks in the Midwest League. Bobby, the second youngest, played one season of minor-league ball in 1972 before moving on to have a lucrative career in real-estate development.1 The brother who was the most promising was Ken Brett, the second oldest, who was affectionately known as “Kemer” throughout the Brett household.

Ken Brett pitched in 14 major-league seasons with 10 different teams. He made his major-league debut in Fenway Park with the Boston Red Sox on September 27, 1967, pitching the last two innings in a 6-0 loss to the Cleveland Indians. Two weeks later, at 19 years old, he replaced Sparky Lyle on the postseason roster to become the youngest pitcher in World Series competition when he threw 1⅓ scoreless innings in his two relief appearances. Sitting in the stands cheering him on, was 14-year-old George as Ken was allowed to invite his parents, siblings, and high-school coach John Stevenson to witness the fall classic.2

In 1973, while pitching for the Phillies, Ken surrendered Hank Aaron’s 700th home run. A year later, as the lone representative of the Pittsburgh Pirates, he was the winning pitcher in the 1974 All-Star Game. Although Ken’s pitching career was plagued by arm problems, he was also an excellent hitter. In 1973 he set a record for the most consecutive games by a pitcher (four) with a home run. On October 3, 1981, his “little” brother George had come full circle: from watching his older brother pitch in the World Series to playing alongside him in his final major-league appearance. Kemer pitched two innings, allowing one run, as the Royals lost 8-4 to the Oakland A’s in Kansas City. George homered in the sixth off Rick Langford.

The Brett boys grew up in El Segundo, California. John, Ken, and Bobby were born in Brooklyn, New York. George was born on May 15, 1953, in Glen Dale, West Virginia, before the family moved out west when he was 2 years old.

Their father, Jack Brett, was a Brooklynite who cheered for the New York Yankees. Although he came from a good household (his father worked on Wall Street), he dropped out of high school to work in a factory. By the age of 18, he enlisted in the US Army and fought in World War II. His tour of duty ended when he was shot in the leg in France. Upon returning home, he enrolled at Pace College in New York, where he earned a degree in business administration. He worked as an accountant for Mattel Toys. In 1945 he married Ethel Hansen.

Ethel, who worked as a bookkeeper for a furniture company, was a loving, nurturing mother. Jack was the disciplinarian in the household, whose wrath was felt mostly by George. While the older siblings seemed to apply themselves both athletically and academically, George was seen as somewhat lazy and lacking motivation. He preferred bumming around Redondo Beach to playing baseball. George later admitted that if it were not for his baseball skills, he more than likely would have wound up as a bartender or a construction worker.

Like his brothers before him, 7-year-old George began playing Little League baseball at Recreation Park in El Segundo. As a child his favorite players were Mickey Mantle, Carl Yastrzemski, and Brooks Robinson. By the ninth grade, George was only 5-feet-1 and 105 pounds when he tried out for the El Segundo High School baseball team. Initially Dave Reed, a junior-varsity coach, wanted to cut George from the squad for his lack of size, but he was overruled by varsity coach John Stevenson, who coached George’s three older brothers. As it turned out, the ambidextrous George broke his wrist and had to sit out his freshman year anyway.3

Over the next two years George grew and filled out. His first love was football, and George was the starting quarterback for his high school team. Because of his propensity for throwing interceptions, he was converted to a wide receiver in his senior year. As a high-school baseball player, he could never measure up to his older brother Ken, who was already pitching for the Red Sox. He was also overshadowed by high-school teammate Scott McGregor, who went on to have a 13-year major-league career pitching for the Baltimore Orioles.

Initially Brett was a third baseman, but he moved to shortstop in his junior year. Throwing right-handed but batting left-handed, he imitated a Yaz-like stance at the plate. He established such a flair for the dramatics in crucial situations that his teammates nicknamed him “Mr. Drama.”

By Brett’s senior year the 1971 El Segundo Eagles were one of the finest high-school baseball teams ever assembled in the California Interscholastic Federation (CIF). They posted a 33-2 record and won the CIF championship. Six players, including Brett, were drafted by major-league teams, yet George was never offered a college scholarship for his baseball prowess.4

Because Brett still had some baby fat around his midsection, many scouts passed on him. Even some of the scouts for the expansion Kansas City Royals were skeptical. However, scouts Tom Ferrick and Rosey Gilhousen saw Brett as a diamond in the rough. Gilhousen pushed the hardest for the Royals to draft Brett, basing his assessment on the intangibles of desire, instincts, and aggressiveness. He persuaded the Royals vice president for player personnel, Lou Gorman, to see Brett in action during a high-school game. The fact that Coach Stevenson and Gorman were in the Navy together may have helped sway the Royals into taking Brett with the fifth pick in the second round of the June 1971 amateur draft.)

Brett began his professional career in the rookie-level Pioneer League. On June 15, 1971, shortly after his high-school graduation, he arrived in Billings, Montana, to play for the Mustangs. Garbed in beach-bum attire when he met his new manager, Gary Blaylock, Brett was politely told to wear some shoes and a shirt the next time they met.5 It was there that Brett was converted from a shortstop to a third baseman.6 For the season Brett batted .291 with 5 home runs and 44 RBIs.

He was sent to the Winter Instructional League in Sarasota, Florida, between seasons and was promoted to San Jose of the Class-A California League for 1972. In June his brother Bobby became a teammate when he signed with the Royals. He played 19 games with the Bees before calling it a career. George finished the season with a .274 batting average, 10 home runs, and a team-leading 68 RBIs.

In 1973 Brett was invited to the Royals spring-training site in Fort Myers, Florida. On the flight to Fort Myers he met another Royals prospect, Jamie Quirk.7 The two would form a lifelong friendship, but for now they were competing for a spot on the Royals Opening Day roster.

It didn’t take long before Brett was back on a plane heading to Omaha after he was one of the first cuts in spring training. Playing for the Omaha Royals in the American Association, Brett made the Triple-A all-star team and finished with a batting average of .284, 8 home runs, and 64 RBIs before being called up to the Royals. Filling in for the injured Paul Schaal, Brett made his big-league debut on August 2, 1973, at Comiskey Park in Chicago. Batting eighth, Brett lined out to the pitcher, Stan Bahnsen, in his first plate appearance. The second time up he recorded his first major-league hit — a broken-bat bloop single to left field. Brett finished the season with a .125 batting average in limited action as Kansas City improved to 88-74, six games behind the league-leading Oakland A’s.

It is worth noting that Brett wasn’t the only player making his Royals debut that year. The Royals had acquired outfielder Hal McRae in an offseason trade with the Cincinnati Reds. McRae’s vehement passion for the game was a major influence on Brett as the culture of the Royals clubhouse gradually changed in the coming years.8

Heading into 1974, it was no secret that Royals manager Jack McKeon was not overly thrilled with having Brett on his team.9 Despite the fact that incumbent third baseman Paul Schaal led the majors with 30 errors in 1973, Brett found himself back in Omaha to start the new season. In fairness to Schaal, the newly constructed Royals Stadium featured artificial turf which may have contributed to his defensive struggles.10

On April 30, 1974, Schaal was traded to the California Angels for outfielder Richie Scheinblum. Frank White filled in at third base for a few games before the Royals recalled Brett from Omaha. When Brett took over for White in early May, he struggled defensively and offensively. Nearing the All-Star break, Brett was barely hitting above .200 when hitting coach Charley Lau approached him. For the rest of the season, Lau worked with Brett daily on revamping his swing. One day, after Brett didn’t show up for practice, Lau called him a “mullet head” for his complacency.11 (It was later shortened to “Mullet.”) Suffice it to say that Brett never missed a session with Lau again.

Under Lau’s tutelage, Brett’s batting average soared to .292 with three games left in the season when Jack McKeon unexpectedly fired Lau.12 A devastated Brett collected one hit in those last three games and finished with a .282 average.13

The 1975 season was one of transformation for Brett and the Royals. It began with Brett changing his jersey number from 25 to his more familiar number 5. He did this to pay homage to one of his favorite players (who also played third base), Brooks Robinson.14 After 96 games into the season, the Royals replaced manager McKeon with Whitey Herzog. One of the first things Herzog did was to rehire Charley Lau as their hitting coach. Brett went on to lead the league in hits (195) and triples (13). He also finished with a .300 batting average (.308 to be exact) for the first time in his professional career. The Royals posted their best record so far, finishing 20 games above .500, but were still spectators for the postseason. Kansas City fans were growing weary of seeing the Oakland A’s win another divisional title, their fifth in a row.

When Charlie O. Finley moved the team to Oakland before the 1968 season, many fans in Kansas City were ambivalent about their departure. The Athletics never finished above .500 in the 13 years they played in Kansas City, yet it was demoralizing to see the A’s finish above .500 in their inaugural season in Oakland. Like a bitter divorce, the animosity only got worse as the A’s continued to get better, culminating in three straight World Series titles (1972-1974).15 The Royals finally seized their opportunity to wrest the division crown away from the A’s in 1976, after Finley began to dismantle his dynasty in an effort to save money.

The ’76 season began with Brett making headlines almost immediately. From May 8 to 13, he collected three hits in six consecutive games to tie a major-league record.16 The Royals claimed first place by a half-game on May 19 and never relinquished their lead. By August 6 they had built it into a 12-game lead over the second-place A’s. During an extra-inning game against the Cleveland Indians on August 17 at Royals Stadium, Brett pulled off one of the rarest feats in baseball by stealing home for the walk-off win.17 From that point on, the Royals sputtered with an 18-27 record, but were able to stave off a late-season surge by the A’s to capture their first division title by 2½ games.

Even though the Royals were headed to the postseason in 1976, the last game of the regular season was marred in controversy when Brett edged out McRae for the AL batting title. With the Royals trailing the Minnesota Twins 5-2 in the bottom of the ninth, Brett came up to bat with one out and nobody on base. He lofted a routine fly ball to left field, which many felt could have been caught by Twins outfielder Steve Brye. Instead, Brye played it into an inside-the-park home run, thereby giving Brett the title. McRae, an African-American, was outraged by Brye’s lackadaisical attempt and accused him of being a racist. Brett felt terrible about the whole situation, and said that if he could split the award in half he would gladly do it. In spite of his disappointment, McRae held no ill will toward his friend and teammate as they embarked on their first American League Championship Series against the New York Yankees.18

Brett had an inauspicious beginning to his postseason career when his two errors led to two runs in the first inning of Game One at Royals Stadium. The Royals lost, 4-1, but they managed to push the series to the decisive Game Five. During that game, at Yankee Stadium, the national audience got their first glimpse at Brett’s penchant for delivering in crucial moments as he belted a three-run homer to tie the game, 6-6, in the top of the eighth inning. That home run is often forgotten as Chris Chambliss led off the bottom of the ninth with a solo homer that put the Yankees in the World Series for the first time in 12 years.

Although the Royals came up short in the ALCS, they would continue to dominate the American League West by appearing in six of the next nine postseasons. It is not a coincidence that 1976 was also the first of Brett’s 13 consecutive All-Star selections. When the season ended, he was the runner-up to Thurman Munson for the American League Most Valuable Player.

The 1977 ALCS was a rematch of 1976. In the deciding Game Five at Royals Stadium, Brett hit an RBI triple off Ron Guidry in the first inning. When Brett slid in hard at third, Yankees third baseman Graig Nettles took exception and kicked him in the face. Brett jumped up with a haymaker to ignite a bench-clearing brawl. After order was restored, both players were allowed to stay in the game. Losing 3-2 in the top of the ninth, New York scored three unanswered runs to snatch the pennant away from Kansas City once again. For the second year in a row, the Royals lost the pennant to the Yankees in the final inning of the final game.

With their rivalry now firmly solidified, the 1978 postseason marked the third straight year the Royals faced the Yankees in the ALCS. This time the Royals won only one game. Brett provided some highlights in the third game by becoming the fourth player to hit three home runs in a postseason game.19 All three homers were served up by Catfish Hunter. To Brett it was small consolation as the Royals lost, 6-5. They would lose more than the series as dissension was festering among the ranks. During the regular season Whitey Herzog was losing his patience with the results of his hitting guru, Charley Lau.20 Shortly after the ALCS, the Royals announced that Lau would not return in 1979. Seizing the opportunity, the Yankees quickly hired Lau as their hitting coach.

Brett began 1979 by breaking his right thumb in an offseason charity basketball game.21 Because of the injury, plus the absence of Charley Lau, Brett got off to a slow start but he finished the season with a league-leading 212 hits and 20 triples. His .329 batting average was second in the league to Fred Lynn’s .333. Despite Brett’s production, the Royals missed the playoffs for the first time in four years. Whitey Herzog and all his coaches were fired. The future looked bleak.22

The Royals had won three division titles under Herzog, but never got past the Yankees in the Championship Series. Entering the 1980 season, they were now playing for rookie manager Jim Frey. Frey, hired just days after his Baltimore Orioles lost the 1979 World Series to the Pittsburgh Pirates, had been a coach under Earl Weaver for 10 years.

On May 15, 1980, Brett’s 27th birthday, the Royals were 16-14 while enjoying an offday. In lieu of a ballgame it was the nationally televised Miss USA Beauty Pageant that had fans in Kansas City cheering. The contest’s “Miss New York,” Debra Sue Maurice, informed host Bob Barker that she was dating George Brett. Brett, who tried to downplay his long reputation of being a ladies’ man, was caught off-guard by her statement. He acknowledged having had a few dates with Miss Maurice but nothing more serious than that.23

Whatever distraction it may have caused was insignificant as the bigger story of the 1980 season was Brett’s unlikely pursuit of a .400 batting average. During a June 10 game in Cleveland, he tore a ligament in his right foot while trying to steal second base.24 Unable to play again until July 10, Brett was batting .337 at the time he was hurt. No one could have predicted that he would be soaring around .400 by season’s end. Beginning on July 18, Brett started a 30-game hitting streak that would help catapult him over the vaunted mark. He topped .400 on Sunday, August 17, when he went 4-for-4 against the Toronto Blue Jays in Kansas City. His fourth hit, a bases-clearing double in the eighth inning off Mike Barlow, put him over the top. As he stood on second base, acknowledging the hometown crowd, the scoreboard flashed “.401.”25

Whatever distraction it may have caused was insignificant as the bigger story of the 1980 season was Brett’s unlikely pursuit of a .400 batting average. During a June 10 game in Cleveland, he tore a ligament in his right foot while trying to steal second base.24 Unable to play again until July 10, Brett was batting .337 at the time he was hurt. No one could have predicted that he would be soaring around .400 by season’s end. Beginning on July 18, Brett started a 30-game hitting streak that would help catapult him over the vaunted mark. He topped .400 on Sunday, August 17, when he went 4-for-4 against the Toronto Blue Jays in Kansas City. His fourth hit, a bases-clearing double in the eighth inning off Mike Barlow, put him over the top. As he stood on second base, acknowledging the hometown crowd, the scoreboard flashed “.401.”25

A week earlier, on August 11, the Royals had signed George’s older brother, left-hander Ken Brett, to help out in their bullpen. Released by the Dodgers in the spring because of a sore left elbow, Ken was playing for the semipro Orange County A’s when the Royals came calling.26 He made five appearances with the Omaha Royals before making his Kansas City debut on September 1 against the Brewers. With the Royals down 4-1 to Milwaukee, Ken relieved Rich Gale in the top of the fourth to get the final out. He remained in the game to pitch four more shutout innings. Whether it was coincidence or a backhanded tribute, Ken wore the number 25, the same number his “little” brother wore when he first came up to the Royals in 1973. Regardless of the motive, playing alongside his older brother at the major-league level is one of George’s most cherished moments in baseball.27

With his brother by his side, George’s average hovered around .400 for over a month. It wasn’t until September 20, when he went 0-for-4 against Oakland, that his average dipped below.395. Plagued by nagging injuries which caused him to miss 45 games during the season, the media attention also took its toll. To avoid the press, the Brett brothers would often drive together in George’s Mercedes and park in a tunnel behind the Royals bullpen for an easy escape after games.28 Eventually his average dropped to .390 to close out the campaign. As of 2018, it was the closest any player has gotten to .400 since Ted Williams batted .406 in 1941.29 Additionally, Brett led the league in on-base percentage (.454) and slugging percentage (.664). It is worth noting that he also belted 24 home runs yet only struck out 22 times in 515 plate appearances.

The Royals clinched their division by 14 games over the second-place A’s. For the fourth time in five years, they would face the Yankees in the American League Championship Series. The Royals won the first two games, leaving them one win away from their first World Series appearance. Game Three featured one of the most memorable moments in playoff history. The Royals were trailing 2-1 in the top of the sevento on, Brett stepped in to face the imposing Gossage and hammered the first pitch to him for a three-run homer to put the Royals ahead. That held up to give the Royals a 4-2 victory and their first trip to the World Series.

The Royals faced the Philadelphia Phillies, who were also vying for their first Worlh. Yankees pitcher Tommy John got the first two outs before Willie Wilson doubled. Reliever Goose Gossage gave up a single to U L Washington and Wilson went to third. With two out and twd Series title. The first two games were won by the Phillies in Veterans Stadium. In the second game Brett began to feel severe pain. After collecting a walk and two singles, he asked to be taken out of the game. On the way back to Royals Stadium for Game Three, Brett went to St. Luke’s Hospital in Kansas City for minor surgery to have hemorrhoids removed. It was national news by the time Game Three got underway as Brett found the grit to suit up. In his first at-bat, just hours after the surgery, Brett drove a Dick Ruthven pitch into the right-field stands for a home run that gave the Royals a 1-0 lead. The Royals held on to win the game, but lost the Series in six games.

On an individual basis, 1980 would prove to be Brett’s most defining year as a major leaguer. He won the American League Most Valuable Player Award, but individual accomplishments didn’t matter much to Brett. He was disappointed that he fell short of hitting .400, but admitted that it would have eased his pain if the Royals could have won the World Series.30

With his pursuit of .400, his tryst with a beauty pageant contestant, his first World Series appearance, and his hemorrhoids, Brett’s stature was now on a national level. His waning days of casually hanging out in Kansas City with teammates Jamie Quirk and Clint Hurdle for burgers and beers in the bars of Westport and the Country Club Plaza were now over.31

A players strike in 1981 divided the season into two halves. Manager Jim Frey was fired after the team went 10-10 to start the second half, and was replaced by former Yankees skipper Dick Howser. Under Howser the Royals went 20-13 to finish with a second-half record of 30-23, earning them a playoff berth; they were swept by the Oakland A’s in the American League Division Series.

The Royals missed the playoffs altogether in 1982 and 1983. Brett continued to put up decent numbers in those two seasons, although he missed a combined 57 games during that span. However, one of his games stood out: It was played on July 24, 1983, at Yankee Stadium and is referred to in baseball lore as “The Pine Tar Game.”

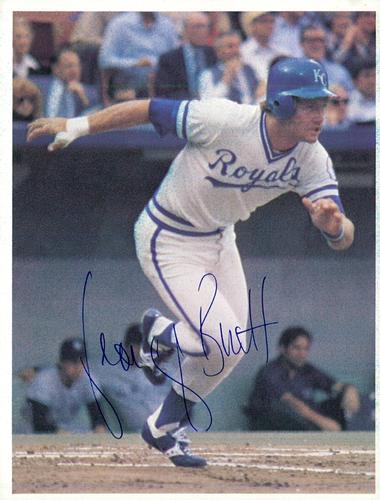

Heading into the game, the Yankees and Royals were two games back in their respective divisions. The Yankees were winning 4-3 entering the top of the ninth inning. Yankees pitcher Dale Murray retired the first two Royals hitters before surrendering a single to U L Washington. Yankees manager Billy Martin replaced Murray with Goose Gossage to face Brett. Brett fouled off the first pitch. The next pitch was up and in, but Brett was able to get the barrel of the bat on the ball and tomahawked it over the right-field wall to give the Royals a 5-4 lead. As Brett circled the bases, Martin was out of the Yankees dugout to have the umpires inspect Brett’s bat for excessive pine tar, insisting that Brett had violated Rule 1.10(c), which stated that “a bat may not be covered by such a substance more than 18 inches from the tip of the handle.%

Full Name

George Howard Brett

Born

May 15, 1953 at Glen Dale, WV (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.