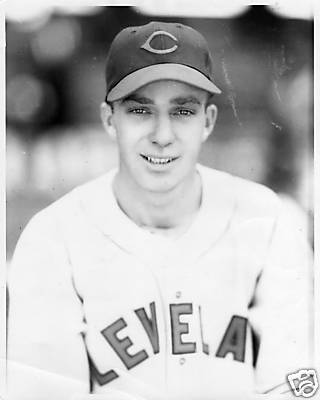

George Case

George Case was a four-time major-league All-Star who devoted almost 50 years of his life to the game he loved. His playing career, cut short by injuries, spanned 11 years (1937-47), ten years with the Washington Senators and one with the Cleveland Indians. After his playing days ended he remained in the game in various roles: college baseball manager, major-league coach, minor-league instructor and manager, and scout. In spite of his on-field success and the considerable fame he achieved in his day, Case is best remembered as a man with a strong sense of humility who rarely spoke of his many accomplishments – a man known to have his priorities in order. He was described by those who knew him best as “a special person,” and was a devoted husband, father, and grandfather.

George Case was a four-time major-league All-Star who devoted almost 50 years of his life to the game he loved. His playing career, cut short by injuries, spanned 11 years (1937-47), ten years with the Washington Senators and one with the Cleveland Indians. After his playing days ended he remained in the game in various roles: college baseball manager, major-league coach, minor-league instructor and manager, and scout. In spite of his on-field success and the considerable fame he achieved in his day, Case is best remembered as a man with a strong sense of humility who rarely spoke of his many accomplishments – a man known to have his priorities in order. He was described by those who knew him best as “a special person,” and was a devoted husband, father, and grandfather.

A natural athlete in his youth, George Case had one remarkable talent that separated him from his peers: his blazing speed. He wasn’t just fast. George Case could run like the wind. This extraordinary ability became his ticket into professional baseball; and once he made it to the majors, he fine-tuned his skills and emerged as the premier basestealer of his generation. According to author Mark Stang: “His raw speed and ability to read pitchers and catchers made him the most feared basestealer in either league.” 1

George Washington Case Jr. was born on November 11, 1915, in Trenton, New Jersey, the third of three children of George Washington Case Sr. and his second wife, Clara McIntyre. George Sr. was 59 at the time of George Jr.’s birth and had an older son, Cliff, from a previous marriage. Cliff was 30 years old when his half-brother George was born. The couple also had two daughters, Audrey and Gladys. George Case, Sr. was a butcher and businessman who founded Case’s Pork Roll in 1874. Case’s retail store was still in existence as of 2013. George Sr. was a noted sprinter in his youth, and was a source of his younger son’s exceptional athleticism. His older son, Cliff, also played professional baseball before giving up the game for a career with Case’s Pork Roll, a business he ran for many years.

George Jr. attended Gregory Elementary School, and Junior High Three, both in Trenton. During his youth he and his future wife, the former Helen Farrell, lived within two blocks of each other and attended grade school, junior high, and high school together. They were married in 1937 and had two children: a son, George Washington Case III, and a daughter, Robin. The two siblings were separated in age by 16 years. George W. Case III was executive Director of SABR from 2000 to 2002.

George Case attended Trenton High, graduating in 1934, followed by two prep-school years at the Peddie School in Hightown, New Jersey. According to his son, during his time at the Peddie School, “He was deciding whether to accept a college scholarship to Brown University or become a professional baseball player.”2

During his high-school years he acquired the nickname Casey because of his penchant for reciting “Casey at the Bat” for his teammates and relatives, an endearing family tradition he passed on to his son.3 He was first team All-State in baseball and basketball in high school. In 1934 he played in an exhibition game against future Hall of Famer Jimmie Foxx. The two became friends and remained so for many years. When Foxx played for the Philadelphia A’s he often visited the Case home in Trenton – and always replenished his supply of Case Pork Roll.4

As a pitcher and second baseman with terrific foot speed, George Case was noticed by local scouts. Before long the talented teenager came to the attention of Philadelphia Athletics owner-manager Connie Mack. Observing young George in a tryout Mack suggested a switch to the outfield, where his speed would be a valuable asset. George accepted Mack’s advice and developed into an exceptional defensive outfielder. He remained an outfielder for the rest of his career except for three games as a pitcher in the minors.

Since the A’s were stocked with outfielders at the time, Mack advised his friend Clark Griffith of the Washington Senators to take a look at the young speedster.5 In 1936 Washington scout Joe Cambria, who signed many of the Senators’ best players during the 1930s and ’40s, inked George to his first professional contract. He landed with the York White Roses, a Senators affiliate in the New York-Pennsylvania League. Later in the season he was transferred to the Trenton Senators in the same league, a team owned at the time by his half-brother Cliff Case. In Case’s two minor-league seasons he played in 175 games and hit .313. While at Trenton Case lived at home and commuted to the ballpark. He and Edgar Leip (Washington 1939, Pittsburgh 1940-42) were the only two players to be born in Trenton, play minor-league baseball in Trenton, and go on to the major leagues.

With word of his extraordinary speed spreading throughout the Washington organization, the parent club called Case up a “look-see” in September 1937. The 6-foot, 183-pound right-handed-hitting outfielder made an inauspicious big-league debut on September 8 in a game at Philadelphia’s Shibe Park. He went 0-for-4 against Athletics pitcher George Caster in a 2-0 Washington loss in the first game of a doubleheader. In the second game he was also hitless in four at-bats. He recovered from this temporary setback and finished the season strong, hitting .289 in 93 at-bats. 1938 Case hit .305 in 107 games. His breakout year came in 1939, when he hit.302, led the Senators in runs (103), and topped the American League in steals (51). For the next seven years Case was baseball’s most feared and most successful basestealer. After he was traded to the Cleveland Indians in 1946, his new manager. Lou Boudreau jokingly remarked that he was relieved he no longer had to worry about “that pest” George Case on the bases.

In 1940 Case hit his stride and blossomed into a star. He achieved career highs in runs (109) and hits (192), and had 35 steals. More success followed in 1941 with 33 thefts and the league lead in outfield assists (21). Case hit a career-high .320 in 1942, scored 101 runs, added 44 steals, and was caught stealing only six times. In 1943 he won another stolen-base title, his fifth straight. His 61 thefts that year equaled the highest single-season mark from 1921 through 1961. He endured an injury-plagued season in 1944 as he slipped to a .250 average, an uncharacteristically low 63 runs scored, and a second-place finish to Snuffy Stirnweiss in stolen bases (49). In 1945 Case’s batting average climbed to a more respectable .294 with another second-place finish to Stirnweiss in stolen bases (30) as he placed ninth in MVP voting.

In December 1945, with a slow-healing separated shoulder and back problems taking their toll from many years of hard sliding, Case was traded to the Cleveland Indians for Jeff Heath. At age 30 he sensed that his body was starting to break down. Of his evolving approach to base stealing, he said, “I’ve reached a stage in my career when I realize that I must conserve myself if I’m going to last another ten years.” 6

Case’s last stolen-base title came with the Indians in 1946 (28), although his batting average (.225) and runs (46) continued to slide. In March 1947 Case was traded back to the Senators in exchange for pitcher Roger Wolff. After hitting .150 in 36 games he announced his retirement at the age of 31. He played his last game on August 3, 1947. The ten-year goal proved to be elusive.

Case’s last stolen-base title came with the Indians in 1946 (28), although his batting average (.225) and runs (46) continued to slide. In March 1947 Case was traded back to the Senators in exchange for pitcher Roger Wolff. After hitting .150 in 36 games he announced his retirement at the age of 31. He played his last game on August 3, 1947. The ten-year goal proved to be elusive.

Case stole 349 bases in his career with an outstanding 76.2 percent success rate. He ranked ninth in American League history in career steals at the time of his retirement. In 1986 writer Nicholas Dawidoff described Case’s base-stealing technique: “Like many great basestealers, Case didn’t take a big lead, but he was able to get a phenomenal jump on the pitcher. Hall of Fame pitcher Early Wynn says: ‘It seemed like he was always started at full speed.’ ”7

In the same article, Case commented on why he never stole 100 bases, and also proffered a contrast between today’s basestealers and those of his day: “Baseball was played a lot differently then [when I played]. I never stole third with two out or stole second when we were three or four runs down. In the 1940s, there were right and wrong times to run. Now that isn’t true. It’s no secret why players get 100 stolen bases today.” 8

Case is the only player to lead the major leagues in stolen bases five consecutive seasons (1939-43). He did it again in 1946, thus topping the American League six times. This achievement tied him with Ty Cobb for the most seasons leading in steals, a mark later broken by Hall of Famer Luis Aparicio. Case’s 321 steals for Washington rank third in franchise history, behind Clyde “Deerfoot” Milan (495), and Hall of Famer Sam Rice (346). He said of his remarkable success, “You just can’t run on a sign and be a good basestealer. All the time I played in Washington under Bucky Harris and Ossie Bluege, I never was given a sign.” 9

In addition to his skill on the basepaths, Case had many other career highlights. As a line-drive-hitting leadoff man, he compiled a respectable .282 lifetime batting average in 1,226 games, with 1,415 hits and a .341 on-base percentage playing for mostly second-division Washington teams. He hit over .300 three times and scored over 100 runs four times, leading the league in 1943. He struck out only 297 times in 5,016 at-bats (5.9 percent). Case was one of the hardest players ever to double up, hitting into a double play only once in every 94 at-bats. (As of 2013 he ranked in the top five in this category.) Case led the American League in plate appearances in 1940 and ’41, and had three top-ten finishes in hits. He earned four All-Star selections (1939, ’43, ’44, and ’45) and tied a major-league record with nine hits in a doubleheader against Philadelphia in 1940. He was on the field when Lou Gehrig gave his “Luckiest Man” speech on July 4, 1939, at Yankee Stadium, and caught the last ball that Gehrig hit in his major league career, a fly ball to center on April 30, 1939.

Case was thought by many to be the fastest ballplayer in the game between the 1920s and ’50s. He was possibly the fastest ever to play the game, at least until the time of his retirement. His baseball mentor, Clyde Milan, Washington’s all-time leading basestealer, thought so and once paid him the ultimate compliment: “George Case was the fastest man ever to play baseball. … He was faster than Ty Cobb, Eddie Collins, Max Carey. …” 10

This view was also shared by sportswriter Edwin Rumill of the Christian Science Monitor: “In the person of George Washington Case, the senatorial outfielder, you are looking at the fastest human in the American League. …” 11 This claim is not without merit. In 1943 Case was credited with the fastest time ever circling the bases. In a pregame exhibition at Griffith Stadium he was clocked by an AAU timer in 13.5 seconds from a standing start. This broke the previous record of 13.8 seconds set by Hans Lobert. In 1946 Cleveland Indians owner Bill Veeck staged one of his famous promotions, pitting Case against the legendary Jesse Owens in a 100-yard dash. Case lost to “The World’s Fastest Human” by a mere one-tenth of a second, possibly the only race he ever lost.

In another promotional race in 1946 staged by Clark Griffith at Griffith Stadium, the speedster was matched against super-fast rookie Gil Coan, who at the time was seven years Case’s junior. Although Case was ailing from a bad back, he was clocked at 10 seconds flat in the 100-yard dash, beating the stunned rookie by half a stride.

Case’s second career in baseball began right after he retired as a player. In 1947 he opened a sporting-goods store, George Case’s Sports Center, in Trenton, which he ran until 1960. From 1950 to 1960 he coached the Rutgers University baseball team, splitting his time between the store and the university during the baseball season. In his first year at the Rutgers helm, he guided the Scarlet Knights to their only College World Series berth. His son George W. Case, III played for his dad during his sophomore year at Rutgers (1960).12 During this busy time, Case also hosted a daily 15-minute radio show for WTTM in Trenton (1958-60).

Case later became the third-base coach for the expansion Washington Senators under manager Mickey Vernon (1961-63); managed the Triple-A Hawaii Islanders in the Pacific Coast League (1965-66); coached for the Minnesota Twins (1968); managed the Class A (short season) Oneonta Yankees (1969-72), earning two Manager of the Year Awards; enjoyed a stint as the CBS color commentator alongside play-by-play announcer Jack Whitaker for the backup Game of the Week (1973); scouted for the Yankees, Texas Rangers, and Seattle Mariners (1974-79); and was a minor-league batting instructor for the Mariners (1980-85) until illness forced his retirement from the game. This ended a distinguished baseball career that spanned nearly five decades. In retirement Case devoted much time to his family, including his five grandchildren. He also had time for his lifelong hobby of duck hunting, and even served as a duck-hunting guide in Barnegat Bay, off the New Jersey coast.

Case received numerous awards during his lifetime, including inductions into the Peddie School Athletic Hall of Fame (where he was named “Athlete of the Century”), and the New Jersey Sportswriters Hall of Fame. He was named the New Jersey Professional Athlete of the Year for 1939. True to his humble nature, he rarely spoke of any of these awards.13 His son accepted numerous posthumous awards for his father, including induction into the Washington Hall of Stars (1989), the Trenton Thunder Hall of Fame (1994), and the New Jersey Interscholastic Sports Hall of Fame (2012). 14

Case was an exemplar of the extraordinary athleticism many of his descendants have exhibited, including a grandson who played professional hockey in the Pittsburgh Penguins organization and in Sweden. More important was the legacy of integrity and humility he bequeathed to his proud family, proving that a man can achieve success without compromising his values. This was illustrated in a story related by his son: “While baseball was his life and he deeply loved the game, he remained humble and modest about his successes. There once was an article about him in a local newspaper with the headline ‘George Case, His Three Loves: Family, Baseball, and Duck Hunting.’ One of the highest compliments ever paid to him was from a local resident who said to me after the article appeared: ‘I never even knew your father was a major-league ballplayer!’ ” 15

Like many of his contemporaries from “the greatest generation,” in which modesty was one of the highest virtues, George Washington Case, Jr. would have worn this epitaph with pride. He died on January 23, 1989, in Trenton at the age of 74 following complications from emphysema. He was a resident of Morrisville, Pennsylvania, at the time of his death. He was survived by his wife, Helen (who died in 1996); son George Washington Case III; daughter Robin Davis; and five grandchildren. He was buried in the First Presbyterian Church Cemetery of Ewing in Trenton. Over the years his immediate descendants have grown to six grandchildren and six great-grandchildren, including grandson and family namesake, George Washington Case IV.

Sources

Lee, Bill, The Baseball Necrology (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 2003)

Purdy, Dennis, The Team by Team Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball (New York: Workman Publishing, 2006)

Reichler, Joseph, The Baseball Encyclopedia, Ninth Edition (New York: Macmillan, 1993)

Snyder, Brad, Beyond the Shadow of the Senators (New York: McGraw Hill, 2003)

Spatz, Lyle, ed., The SABR Baseball List & Record Book (New York: Scribner, 2007)

Stang, Mark, and Phil Wood, The Nationals on Parade (Wilmington, Ohio: Orange Frazer Press, 2005)

Dawidoff, T. Nicholas, “Meet George Case, The Best Base Stealer That You’ve Never Heard Of,” Sports Illustrated, October 6, 1986

Rumill, Edwin, “George Case Is the New Speed Champ of the American League,” Christian Science Monitor, August 20, 1938

Milwaukee Journal, August 4, 1945

New York Times, Obituary for George Case, January 24, 1989

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.org

SABR.org

Baseball Hall of Fame Library, player clip file for George Case

George W. Case, III, email correspondence with author, October-November 2013

Notes

1 Mark Stang, The Washington Senators On Parade (Wilmington, Ohio: Orange Frazer Press, 2005), 104.

2 E-mail correspondence with George W. Case, III, October-November 2013 (Case e-mails).

3 Case e-mails.

4 Case e-mails.

5 Case e-mails.

6 “Guy Named George Is Sure to Win the Base Stealing Title,” Milwaukee Journal, August 4, 1945, 4.

7 T. Nicholas Dawidoff, “Meet George Case, the Best Base Stealing You’ve Never Heard Of,” Sports Illustrated, October 6, 1986.

8 Ibid.

9 Stang and Wood, The Washington Senators On Parade, 104.

10 T. Nicholas Dawidoff, “Meet George Case the Best Base Stealing You’ve Never Heard Of,” Sports Illustrated, October 6, 1986.

11 Edwin Rumill, “George Case Is the New Speed Champ of the American League,” Christian Science Monitor, August 20, 1938, 10.

12 Case e-mails.

13 Case e-mails.

14 Case e-mails.

15 Case e-mails.

Full Name

George Washington Case

Born

November 11, 1915 at Trenton, NJ (USA)

Died

January 23, 1989 at Trenton, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.