George Davis

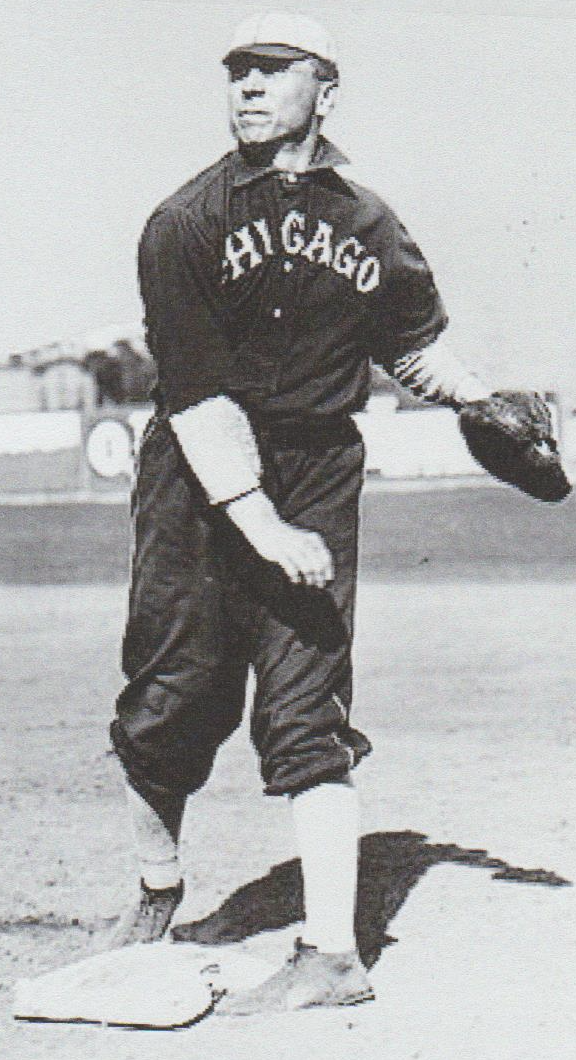

Known as “Gorgeous George” for his graceful play and blond locks, George Davis established himself as one of the game’s most well-rounded players during his 20 seasons in the major leagues. At the plate, the switch-hitting Davis was a model of consistency, batting better than .300 every year from 1893 to 1901. In the field, the shortstop was steady and reliable, leading his league in fielding percentage four times. On the basepaths, the 5’9″, 180-pounder was a constant threat, swiping 619 bases in his career, the third most ever by a player whose primary position was shortstop, behind Honus Wagner and Bert Campaneris. John McGraw described Davis as “an exceptionally quick thinker,” a reputation which led to Davis spending time as the manager of the New York Giants. Yet despite his many achievements, Davis vanished from sight after his career ended and died in obscurity.

Known as “Gorgeous George” for his graceful play and blond locks, George Davis established himself as one of the game’s most well-rounded players during his 20 seasons in the major leagues. At the plate, the switch-hitting Davis was a model of consistency, batting better than .300 every year from 1893 to 1901. In the field, the shortstop was steady and reliable, leading his league in fielding percentage four times. On the basepaths, the 5’9″, 180-pounder was a constant threat, swiping 619 bases in his career, the third most ever by a player whose primary position was shortstop, behind Honus Wagner and Bert Campaneris. John McGraw described Davis as “an exceptionally quick thinker,” a reputation which led to Davis spending time as the manager of the New York Giants. Yet despite his many achievements, Davis vanished from sight after his career ended and died in obscurity.

George Stacey Davis was born on August 23, 1870 in Cohoes, New York, the fifth of seven children of Irish immigrant Abraham Davis and his Welsh wife, Sarah. According to the 1880 census, Abraham supported his family as a machinist. Baseball was becoming very popular in the Albany area during George’s childhood, and Cohoes newspapers place the lad on tavern-sponsored teams as early as 1886. According to these sources, even at this young age Davis was already a switch-hitter.

Davis spent the 1889 season with an Albany semipro team. The following year, the Cleveland Spiders of the National League, looking to replace players who had jumped to the upstart Players League, signed Davis on the recommendation of Albany manager Tom York. Still just 19 years old at the start of the 1890 season, the rookie answered the call by hitting a solid .264, with six home runs, 73 RBI, 22 stolen bases and 35 assists in the outfield, playing mostly center. The following year, Davis proved that his promising debut had been no fluke, as he batted .289 with 115 runs scored, 50 extra base hits and 42 stolen bases. Davis’s excellent and versatile defense allowed Cleveland manager Patsy Tebeau to bounce him between the outfield, third base, second base, and even the pitcher’s box, albeit only for three abominable appearances in which the right-handed thrower yielded seven earned runs in four innings of work.

Prior to the 1893 season, New York Giants manager John Montgomery Ward traded heralded veteran Buck Ewing for the young 22-year old Davis, just off a subpar year in which he had batted .241. Ward installed Davis at third base and the switch-hitter, aided by the new 60’6″ pitching distance, hit an impressive .355 with 119 RBI and a career-high 27 triples. He also set a major league record with a 33-game hitting streak, though the mark would be broken by Bill Dahlen the next year. The New York fans embraced their new player and Ward became a mentor to Davis, who grew a handlebar mustache that mirrored Ward’s, making it difficult to tell the two apart.

In 1895, Andrew Freedman took control of the Giants’ franchise as Ward retired to make use of his new law degree. Freedman jumped on 24-year-old Davis as a replacement because of his intelligence and well-spoken demeanor, making him the youngest manager in baseball history at the time. The Giants struggled under their new skipper, however, going 16-17 before Davis was relieved of his duties.

The Giants’ second manager of the 1896 season was third baseman Bill Joyce, who moved Davis to shortstop. Davis became the leader of the infield and shined with his wide range and above-average arm. In 1897, Davis was spectacular at the plate, where he batted .353 with career highs in RBI (135) and stolen bases (65). He also excelled in his first full season at short, ranking third in the league in fielding percentage at .926 while leading the league in putouts (339) and double plays (67). Davis’s offensive numbers declined in 1898 in line with the entire league and in 1899 he was hampered with injuries. Despite a solid .337 average that year, Davis managed just one home run and 59 RBI for the season.

Prior to the 1900 season, the Giants new manager, Buck Ewing, appointed Davis as field captain, but before long dissension infested the Giants clubhouse. The team split into two cliques, one consisting of leftover New Yorkers, the other of Ewing imports. After a terrible early July road trip, the Giants fell to 21-41, forcing Ewing to resign under pressure. Ewing cried foul accusing Davis of faking a knee injury to stay in New York to conspire against him to steal his job. Following Ewing’s resignation, Davis was named manager of the club, which finished in last place despite posting a solid 39-37 record under Davis.

After a horrid 52-85 1901 season, it was apparent Davis would not be returning as manager of New York and like many other players at the time, he ignored the reserve clause and signed a contract with the White Sox drawn up by his lawyer, John Montgomery Ward. Freedman did not contest the move because he wanted to replace Davis anyway. In his first season in the American League, Davis batted a solid .299, drove in 93 runs and stole 31 bases.

John McGraw took over as Giants manager midway through the 1902 season. After the campaign, McGraw, looking to fill the club’s gaping hole at shortstop, acquired Davis’s signature on a two-year contract to play for New York. The move threatened to destroy the new peace treaty which had been forged between the two leagues that winter. White Sox owner Charles Comiskey threatened legal action. Davis went to Ward who argued, rather disingenuously, considering that he had helped Davis jump his New York contract the previous year, that the reserve clause in Davis’s 1901 Giants contract constituted a legal hold on the ballplayer’s services for the 1902 season, thus overruling any claim the White Sox had on his services. Ward declared Davis was entitled to rejoin the Giants per the new contract. Comiskey counter-attacked by first securing an injunction from an Illinois court, which prevented Davis from playing baseball for any team other than the White Sox in that state. In July, Comiskey obtained another injunction, this one from the U.S. Court of Appeals, which prohibited Davis from playing for any team anywhere other than the White Sox. The National League owners, weary of the dispute, instructed Giants owner John Brush to give up his rights to Davis. In all, the shortstop played only four games for New York that year, and none for Chicago.

Davis returned to a hostility-free White Sox team in 1904 and, paralleling a league-wide decline in offense, batted just .252, although he also swatted 43 extra base hits and swiped 32 bases for the season. Defensively, Davis continued his excellent work, leading all AL shortstops in putouts, assists, double plays and chances per game.

After finishing third in 1904, Chicago improved to second place in 1905, as Davis, now 34, batted a solid .278. In 1906 the veteran was the best offensive performer for the famous “Hitless Wonders,” finishing the year with a .277 batting average and leading the team in doubles (26), slugging percentage (.355), and RBI (80). Because of illness, Davis missed the first three games of that year’s World Series. After going 0-for-3 in Game 4, he rebounded nicely in the critical final two games of the Series, stroking three doubles and a single, and collecting six RBI over the final two games.

The 1906 championship marked the last hurrah for Davis as age and injuries caused his average to steadily decline in 1907 and 1908. By 1909 he was a part-time player, appearing in just 28 games and batting only .132. At the end of the season, the White Sox granted Davis’s request to be released.

Davis managed the Des Moines Western League team in 1911 but much like his major league managerial career, was not successful, finishing the year in last place with a 49-113 record. Afterwards, Davis managed a Manhattan bowling alley from 1911 through 1913 and was featured in a New York paper looking clean-shaven and fit as a star bowler at age 43. From 1913 to 1918 Davis was coach at Amherst College during which he also scouted for the Yankees in 1915 and Browns in 1917. He was last mentioned in the press selling cars in St. Louis in 1918.

Davis vanished from public after that until 1968, when Hall of Fame historian Lee Allen discovered his death certificate. Davis had been admitted to Philadelphia General Hospital in 1934 and three weeks later was transferred to a mental hospital in the city. He died on October 17, 1940, at age 70. The cause was paresis—insanity produced by syphilitic alteration of the brain that leads to dementia and paralysis. His wife, Jane Holden Davis, signed the death certificate and buried him 24 hours later just outside of Philadelphia in an unmarked grave in Fernwood Cemetery. Davis’s family would not learn of his death until years later.

Davis received his due recognition when the Veterans Committee voted him into the Hall of Fame in 1998. Thanks to the (now defunct) George Davis Chapter of the Society of American Baseball Research (SABR) and the Century Monument Company, George Stacey Davis now has a stone at his gravesite.

Note

This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

National Baseball Hall of Fame Library files on George Davis and John Montgomery Ward.

Total Baseball, 8th ed.. Sport Media Publishing, 2004.

Lamb, William F. “George Davis: Forgotten Great.” The National Pastime, Number 17. SABR, 1997.

Mathewson, Christy. Pitching In A Pinch. University of Nebraska Press reprint, 1994.

DiSalvatore, Bryan. A Clever Base-Ballist: The Life and Times of John Montgomery Ward. Random House, 1999.

Berke, Art & Schmitt, Paul. This Date In Chicago White Sox History, Stein and Day Publishers, 1982.

Cohoes Newspaper Clippings, 1886-1892.

Albany Times Union. July 26, 1998.

The Sporting News

New York Times

New York World

Chicago Tribune

www.baseballhalloffame.org

Full Name

George Stacey Davis

Born

August 23, 1870 at Cohoes, NY (USA)

Died

October 17, 1940 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.