Hank Wyse

As of 2013, Hank Wyse held the distinction of being the last Chicago Cubs player to throw a pitch in the World Series. The Cubs and Wyse enjoyed a magical season in 1945 despite losing their seventh consecutive World Series since 1910. Then in his fourth season with the North Siders, the 27-year-old Wyse recorded 22 wins for the pennant winners, and the smooth-tossing right-hander with pinpoint control seemed to have a bright future. But his career was plagued by arm problems and chronic back pain, and he was back in the minors in 1948. Wyse briefly revived his career in 1950 with the Philadelphia Athletics before leaving the majors for good in 1951 with a 79-70 record in eight seasons.

As of 2013, Hank Wyse held the distinction of being the last Chicago Cubs player to throw a pitch in the World Series. The Cubs and Wyse enjoyed a magical season in 1945 despite losing their seventh consecutive World Series since 1910. Then in his fourth season with the North Siders, the 27-year-old Wyse recorded 22 wins for the pennant winners, and the smooth-tossing right-hander with pinpoint control seemed to have a bright future. But his career was plagued by arm problems and chronic back pain, and he was back in the minors in 1948. Wyse briefly revived his career in 1950 with the Philadelphia Athletics before leaving the majors for good in 1951 with a 79-70 record in eight seasons.

As the United States mobilized soldiers for World War I, Henry Washington Wyse was born on March 1, 1918, in the bucolic town of Lunsford in northwestern Arkansas. His parents, John Henry and Minnie Elmira (Mead) Wyse, were of Irish and American Indian stock and raised seven children (four girls and three boys) on their farm. Like their father, a former semipro pitcher, the Wyse boys could be found on local sandlots as soon as they finished their chores at home. An athletic youngster, Hank began playing as a catcher and batterymate for his brother Leonard. The Wyses relocated to another small farming community, McCormick, after the death of father John in 1930. Hank quit school after the eighth grade so he could help support his family during the harsh economic times of the Great Depression. He joined an American Legion team in nearby Harrisburg, and was gradually moved to the mound to showcase his rocket right arm. From 1934 to 1936 Wyse worked for the Pointsett Lumber company in Truman, Arkansas, and pitched and played outfield for the company’s semipro team.

Hank’s initial big break came in 1937 when he moved to the Kansas City area, where he found employment as a sheet-metal worker and later as a welder in a factory. Wyse pitched for the company team in a local semipro league, and also played for Goldman’s Jewelry, a team in the competitive Ban Johnson League. That squad was skippered by former big-league pitcher Roy Sanders, who recognized Wyse’s raw talent. Wyse emerged as a star, once tossing 34 consecutive innings without surrendering an earned run, and gained additional exposure by throwing batting practice for the Kansas City Blues, the New York Yankees’ affiliate in the American Association.1 Convinced of Wyse’s major-league potential, Sanders wrote to several big-league clubs to tout his young right-hander. Scouts from the Yankees, the St. Louis Browns and Cardinals, the Cincinnati Reds, and the Chicago Cubs flocked to see the hurler. After refusing an offer from Yankees scout Bill Essick in 1938 because of the low salary offered, Wyse followed Sanders’s advice and signed with the pitching-starved Cubs the following year.

Assigned to the Moline Plow Boys of Class B Illinois-Indiana-Iowa League in 1940, 22-year old Wyse won his first professional start. By early July he was promoted to the Class A1 Tulsa Oilers of the Texas League, despite a 5.55 earned-run average in 94 innings. For the next 2½ seasons, Wyse was under the tutelage of Oilers skipper Roy “Hardrock” Johnson, a respected minor-league manager and former big-league pitcher who had a few cups of coffee with the Philadelphia A’s in 1918.

After seeing limited action as a reliever in a half-season with the Oilers in 1940, Wyse enjoyed a breakout campaign in 1941. The “kid speed baller” notched a 20-4 record and posted a stellar 2.09 ERA in 202 innings, and earned two more wins in the league playoff.2 “[Wyse] can work on two or three days’ rest and is a real prospect,” wrote The Sporting News.3 The Cubs took note of Wyse’s unexpectedly strong season and invited him to Catalina Island to participate in spring training in 1942. Returned to Tulsa at the end of camp, Wyse proved to be the league’s hottest prospect. His 20 wins and 281 innings ranked second in the league, and were supported by a robust 2.56 ERA.

It was no surprise that Wyse joined the Cubs in September 1942 when the rosters expanded. The sixth-place squad desperately needed pitching and boasted only two starters, Claude Passeau and Bill Lee, who started more the 20 games that season. Wyse debuted on Labor Day in the second game of a doubleheader against the Cincinnati Reds at Cincinnati. In what Cubs beat reporter Edward Burns described as a “sharp performance,” Wyse tossed eight-hit ball over 7⅔ innings, yielding three runs (only one earned) to pick up the win, 5-3.4 Ten days later he hurled the first of 11 career shutouts by blanking the Philadelphia Phillies on eight hits in Philadelphia. Wyse immediately noticed a cultural difference between the big leagues and the Texas League. “Jimmy Wilson was a pretty strict manager,” he said, contrasting his Cubs skipper with the jovial Roy Johnson. “He had an awful close curfew [and] didn’t talk to the players very much, only the older players.”5 Wyse went 2-1 in his four starts in September with an impressive 1.93 ERA, thus raising expectations for 1943.

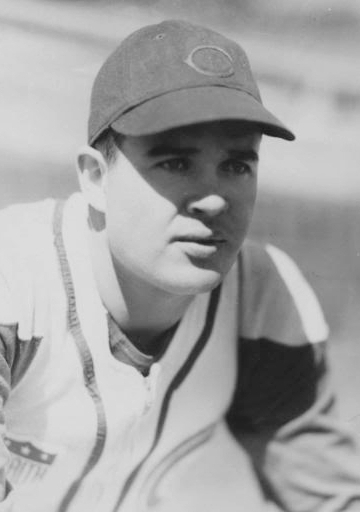

Wyse stood a shade under 6 feet and weighed about 185 pounds with broad, muscular shoulders. He was good-looking with jet-black hair, a dark complexion, high cheekbones, and blue-gray eyes. While newspapers often made reference to his Native American background, Wyse’s teammates teased him about his boyish, baby face (“cherubic” in the words of Edward Burns), which he barely needed to shave.6 But behind Wyse’s youthful appearance lay an intense, competitive nature.

Wyse missed all of spring training in 1943 tending to his gravely ill wife, who died that year. Forced to work himself into shape once the season started, Wyse pitched out of the bullpen with mixed results before making his first start on June 27 with the Cubs in last place. In July Wyse tossed five consecutive complete-game victories, including a career-best 12-inning effort against the New York Giants. Inconsistent in the last two months of the season, Wyse split his time between starts and relief outings. He finished with a 9-7 record, made 15 starts among his 38 appearances, and posted a 2.94 ERA in 156 innings for the fifth-place Cubs.

In the only Opening Day start of his career, Wyse tossed a five-hitter to blank Cincinnati, 3-0, on April 18, 1944, at Crosley Field. The Cubs lost the next 13 games and 16 of 17, resulting in Wilson’s dismissal. Chicago hired Charlie Grimm, manager of the Milwaukee Brewers of the American Association and a former Cubs first baseman and skipper. Grimm, who had guided the club to a pennant in 1935, was a popular choice. Players responded to his laid-back personality and the relaxed tone he set in the clubhouse. “Jolly Cholly” was like a father figure to the players and gave them all nicknames; Wyse’s was “Hankus Pankus.”7 On the Cubs’ starting rotation carousel (nine pitchers started at least seven games), Wyse and 35-year-old fellow right-hander Claude Passeau were the only consistent, dependable starters. Like the Cubs, Wyse finished the season strongly, wining six of eight decisions and posting a 1.46 ERA from August 30 to October 1. In his breakout season, Wyse developed into the staff’s workhorse, pacing the team in wins (16), starts (34), and innings (257⅓).The Cubs went 74-69 under Grimm and finished in fourth place, the first time they finished in the first division since 1939.

Wyse was known as “Hooks” for his knee-buckling curveball, but his pitching arsenal also included an assortment of fastball, screwballs, and changeups. His most effective pitch may have been an “elusive sinker” that he supposedly learned from grizzled former big leaguer Peaches Davis when they pitched together with the Tulsa Oilers.8 Not overpowering, Wyse relied on his pinpoint control and “constantly teasing” stuff to nibble at the high and low corners of the plate.9 Wyse’s control was a product of hard work. “I put a canvas target 18 inches wide in our backyard and threw at that thing by the hour, day after day,” he said of his about his years with Roy Johnson in Tulsa “It was control that made me a pitcher.”10

“Hank’s success,” said skipper Charlie Grimm, “lies mainly in his ability to pace himself down to the last batter. Wyse is strong, but he always conserves himself for the tough spot.”11 Wyse told Edgar Munzel of The Sporting News that pitching in the heat of the Texas League helped him to build up his stamina and avoid unnecessary movement.12 Consequently, Wyse was a fast worker on the mound, regularly completing games in under an hour and 50 minutes. “When I was pitching,” he once said, “as soon as I got the ball, I fired the ball in.”13

In the offseason Wyse worked in the oil fields in Oklahoma. “It was dangerous work,” he once recalled in an interview.14 Workers lost hands and fingers, fell off derricks, braved the brutal winters and weather, and fought with one another. The Cubs got a scare two months before spring training in 1945 when word arrived from Oklahoma that Wyse had fallen off a welding platform and seriously hurt his back. Hank recovered, but for the rest of his career endured chronic lower-back pain. When on the mound, Wyse wore a specially made corset to give his spine and lower vertebrae added support.

The conclusion of the 1944 season gave the Cubs hope in 1945, though no one expected them to unseat the three-time reigning NL pennant-winning St. Louis Cardinals. On April 28 Wyse tossed the best game of his career, yielding only an eighth-inning single to Bill Salkeld to defeat the Pittsburgh Pirates, 6-0, and move the North Siders into a tie for first place. But by the end of June the inconsistent Cubs were in fifth place, struggling to keep their collective heads above water. The outlook looked bleak with Wyse’s status in doubt after he left the team following his seventh win of the season on June 21 to report to his draft board in Oklahoma. But the Cubs’ season was on the precipice of a great shift.

Wyse received a 4-F classification (physically unfit) and joined the Cubs in New York City on July 1 after a grueling 36-hour train ride. That day he tossed a complete game to beat the Giants in the second game of a doubleheader at the Polo Grounds. “His presence,” wrote Jimmy Jordan of the Associated Press, “seemed to give the club a psychological lift.”15 The Cubs proceeded to win 11 consecutive games and 16 of 17 to take over first place. Wyse enjoyed the greatest month of his pitching career in the momentum-turning month of July. He hurled eight complete-game victories in nine starts and posted a 1.84 ERA in 78⅓ innings. With his seemingly effortless delivery with “no frills [and] no wasted motion,” Wyse regularly started on three days’ and even two days’ rest.16

The Cubs’ push to the pennant was given a major boost when they acquired right-hander Hank Borowy from the New York Yankees on July 27. While Borowy garnered many of the headlines, going 11-2 in just over two months with the Cubs, Wyse was content to play second fiddle. At his best when the Cubs needed him most, Wyse concluded the season by tossing four consecutive complete-game victories to lead the Cubs to the pennant.

The “iron man” of the staff ranked second in the NL in wins (22), innings (278⅓), and complete games (23), and tied for second in starts (34). His 2.68 ERA helped the Cubs lead the league in that department for the first time since 1938.17 Wyse earned the respect of his teammates with his fighting attitude. “Guys like (pitcher Paul) Derringer, Passeau, and Wyse,” said outfielder Bill Nicholson, “they understood that everybody behind them was part of the team but they were the main part out there.”18 Wyse finished seventh in the MVP voting, behind teammates Phil Cavarretta, the award winner, Andy Pafko (fourth), and Borowy (sixth).

Wyse was selected to his first and only All-Star Game in 1945, but the contest was canceled because of wartime travel restrictions. He joined six other Cubs on the team: Passeau, first baseman Cavarretta, second baseman Don Johnson, third baseman Stan Hack, and outfielders Nicholson and Pafko.

The day after Borowy’s six-hit shutout of the Detroit Tigers in the Opening Game of the World Series, Wyse faced hard-throwing Virgil Trucks in Game Two, played at Detroit’s Briggs Stadium. Wyse yielded only two hits through the first four frames before the Tigers rocked him for four runs in the fifth, highlighted by Hank Greenberg’s three-run home run. Lifted for a pinch-hitter in the seventh, Wyse was charged with the 4-1 loss.

The Series shifted to Chicago for the final four games with the Cubs leading two games to one. (With wartime travel restrictions still in place even though the war had just ended, the Series was played in a 3-4 format.) Wyse was in line to start Game Six, but Grimm opted for Passeau, who had tossed a one-hit shutout in Game Three. When Passeau ran into trouble with one out in the seventh, Wyse came on in relief and was clobbered. He surrendered three hits and three runs (two earned), issued a walk, and allowed an inherited runner to score while recording just two outs. But the Cubs won the game in the 12th inning to set up a decisive Game Seven. Decades after that game, Wyse still fumed. “I thought I was going to pitch,” he said. “I thought it was a mistake [to pitch Borowy].19 Borowy was lifted without registering an out, and the Cubs were in a five-run hole by the time they came to bat in the first. Wyse, the sixth and final pitcher of the game, tossed a 1-2-3 ninth in mop-up duty in a soul-crushing 9-3 loss. As of the end of the 2013 season, Wyse was the last Cubs hurler to throw a pitch in the World Series.

In 1946 a weak-hitting, injury-prone, and aging Cubs squad failed to replicate the magic of the previous season. After leading the NL in hitting in 1945, the Cubs dropped to third in ’46, and only two position players appeared in at least 120 games. The pitching was weakened by the loss of 16-game winner Derringer; 13-game winner and ERA champion Ray Prim, won only twice; 17-game winner Passeau registered only nine victories; and Borowy who had won a combined 21 games with the Yankees and Cubs, won 12. Wyse, whose demise in the World Series was a product of “exhaustion and wildness,” according to Edward Burns, pitched consistently, duplicating his 2.68 ERA (seventh best in the NL) from the previous season, but managed just a 14-12 record.20 Wyse was a hard-luck loser as the Cubs scored three runs or fewer (15 total) in 11 of his losses. Not known for his hitting, Wyse batted a career-best .243 (18-for-74), well above his career average of .163 in 435 at-bats.

Stamina had been one of the keys to Wyse’s success the previous three years, but the right-hander struggled going deep in ballgames in 1947 and was banished to the bullpen in June. Edward Burns noted Wyse’s “inability to survive tough innings” and suggested that he suffered from a sore arm.21 Vehemently denying any injuries, Wyse countered that his problems came from being in poor shape, “pressing” too hard when he pitched, and not relaxing on the mound.22 Most alarming was the loss of Wyse’s impeccable control (his walks per nine innings rose to 4.1, more than double his previous career rate). While the Cubs fell back to earth with a disappointing sixth-place finish, Wyse concluded a miserable campaign with a 6-9 record and a 4.31 ERA in 142 innings.

After another offseason filled with trade rumors, Wyse reported discomfort in his right elbow during spring training in 1948. According to The Sporting News, physicians detected bone spurs in his right elbow which required x-ray treatment and a cast.23 Despite the bad news, Wyse was kept on the team and expected to return in mid-May. When the Cubs embarked on a 13-game Eastern swing on May 18, Wyse remained in Chicago, still suffering from arm pain. In the meantime, his relationship with the Cubs had deteriorated and his status with the club remained a mystery. Rumors had him going to the Cleveland Indians in a waiver transaction. In an attempt to get back in shape, Wyse threw batting practice for the Chicago White Sox and other AL teams at Comiskey Park, and was even seen in an Indians uniform.24 On May 30 he was optioned on 24-hour recall to the Shreveport (Louisiana) Sports of the Texas League.25 Back in the heat of the Deep South, the 30-year-old Wyse went 12-8 and logged 171 innings.

Wyse was back in Wrigley Field in 1949, but not the one he had hoped for. He was shelled in his five starts with the Cubs’ affiliate in the Pacific Coast League, the Los Angeles Angels, who played their games in the original Wrigley Field. (Cubs Park in Chicago was renamed Wrigley Field in 1927, two years after William Wrigley’s namesake park opened in LA.) Wyse was placed on waivers in early May. Shreveport purchased his contract, and the big right-hander unexpectedly turned in a commanding performance. He went 18-8 and was named to the Texas League All-Star team. Just days after the conclusion of the season, the Associated Press reported that Wyse had been arrested on drunk-driving charges after an accident and later suffered injuries requiring 40 stitches to his arm and back in a jailhouse brawl with other inmates.26 Team officials suspended him for the league playoffs.

The hot-blooded Wyse got another chance in the big leagues when the Philadelphia Athletics, acting on the advice of scout Harry H. O’Donnell, selected him in the Rule 5 draft on November 17, 1949.27 Wyse, however, balked at signing a contract calling for a $5,000 salary. “I can make that much in the Texas League,” he argued.28 But 87-year-old owner Connie Mack, entering his 50th and final season as the A’s skipper, was a tough negotiator. He promised to rework Wyse’s contract based on the pitcher’s early-season results. Wyse’s desire to return to the majors after a two-year stint in the bushes was greater than his desire to squabble over a contract. The highlight of Wyse’s season might have been his debut with the A’s. He threw six-hit ball over six innings against the Washington Senators to earn the win, 6-1, in the second game of the season. “Hooks” managed to win nine games (second-most on the club, which compiled just 52 victories all season) despite possessing the highest ERA among qualifying pitchers in all of baseball (5.85 in 170⅔ innings). In Wyse’s defense, A’s beat writer Art Morrow reported that the right-hander suffered from “back pain” during the season.29

After opening the 1951 campaign with the A’s, Wyse was sold to the Washington Senators on May 16, but an emergency appendectomy delayed his arrival in the nation’s capital by almost three weeks. Thrust into the starting rotation Wyse floundered, still weak from his operation. Less than five weeks after his acquisition, Wyse was sold to the New York Yankees, who assigned him to the Kansas City Blues. Wyse’s career had come full circle, but he was no longer the tireless workhorse with pinpoint control from the late 1930s. On the heels of an 8.63 ERA in 24 innings with the A’s and Senators, Wyse posted a 5.73 ERA for the Blues.

Not yet prepared to give up the sport he loved, Wyse accepted a demotion to the Beaumont Roughriders of the Texas League in 1952. Healthy all season and facing admittedly less rigorous competition, Wyse went 17-15 and logged 240 innings. He concluded his 14-year professional baseball career by going 11-8 with the Tyler (Texas) East Texans in the Class B Big State League, playing in front of about 700 spectators per game far from the bright lights of the big leagues and even the Texas League.

In his eight seasons in the majors, Wyse went 79-70 and carved out a 3.52 ERA in 1,257⅔ innings. He won 115 games and logged 1,495 innings with seven different teams in eight seasons in the minors.

After his active playing days, Wyse settled in the Tulsa area, where he worked as a union electrician. On his player questionnaire from the Baseball Hall of Fame, he reported that he married Virginia Burns in 1952. She was the sister of his second wife, whom he had divorced. Their father, Denny Burns, pitched for Connie Mack’s A’s in 1923 and 1924 and logged 2,800 innings in 16 years in the minors. In 1967 Wyse was inducted into the Oklahoma Hall of Fame;30 and he was inducted posthumously into the Texas League Hall of Fame in 2009.31

Hank Wyse died at the age of 82 on October 22, 2000, in Pryor, Oklahoma. He had been in declining health after suffering a broken hip.32 He was buried in Fairview Cemetery in Pryor.

Sources

Chicago Daily Tribune

New York Times

The Sporting News

Ancestry.com

BaseballLibrary.com

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.com

SABR.org

Hank Wyse player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York

Notes

1 “Four Boys Are Sharing a Dream Of a National Ban Johnson Championship,” Kansas City Star, September 4, 1938, 3B.

2 The Sporting News, June 5, 1941, 5.

3 Ibid.

4 Edward Burns, “Jim Wilson Finds Winning Lineup, So Club Divides,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 8, 1942, 23.

5 Peter Golenbock, Wrigleyville: A Magical History Tour of the Chicago Cubs (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1999), 42.

6 Edward Burns, “Cubs Beat Pirates, 6-0; Wyse Yields 1 Hit,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 29, 1945, A1.

7 Golenbock, 290.

8 Al Vermeer (Newspaper Enterprise Association), “Diligent Study Made Hank Wyse Wise,” Ogden (Utah) Standard-Examiner, August 26, 1945, 13.

9 Jerry Liska (Associated Press), “Hank Wyse Features Control and Teasing Stuff,” Ogden (Utah) Standard-Examiner, August 5,1945, 10.

10 Jimmy Jordan, “Hank Wyse Stays in Background As Cubs Roll Toward Crown,” Fresno Bee – The Republic, August 14, 1945, 40.

11 Ibid.

12 The Sporting News, July 26, 1945, 5.

13 Golenbock, 292.

14 Golenbock, 290.

15 Jordan, 40.

16 Vermeer, 13.

17 Jordan, 40.

18 Golenbock, 286.

19 John C. Skipper, Take Me Out to the Cubs Game: 35 Former Players Speak of Losing at Wrigley (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2000), 29.

20 The Sporting News, October 18, 1945, 2.

21 The Sporting News, June 11, 1947, 4.

22 The Sporting News, March 17, 1948, 6.

23 The Sporting News, April 28, 1948, 8.

24 “If Anybody’s Wise to the Status of Wyse, It Can’t Be Hank,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 30, 1948, A2.

25 Baseball-Reference.com gives May 10 as the date of Wyse’s option; The Sporting News provides May 30.

26 Associated Press, “Bad Weather Grounds Wyse; Misses Houston Grand Jury,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 17, 1949.

27 The Sporting News, February, 1958, 28.

28 The Sporting News, March 29, 1950, 18.

29 The Sporting News, June 28, 1950, 8.

30 John Ferguson, “Koufax, Mantle, Wyse Win Tributes at Tulsa Dinner,” Miami (Oklahoma) Daily News January 13, 1967, 8.

31 “Texas League Hall of Fame,” MILB.com. http://milb.com/content/page.jsp?ymd=20100302&content_id=8648734&sid=l109&vkey=league1.

32 Barry Lewis, “Former Oiler pitcher Wyse dies in Pryor,” Tulsa World, October 24, 2000. [Player’s Hall of Fame file].

Full Name

Henry Washington Wyse

Born

March 1, 1918 at Lunsford, AR (USA)

Died

October 22, 2000 at Pryor, OK (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.