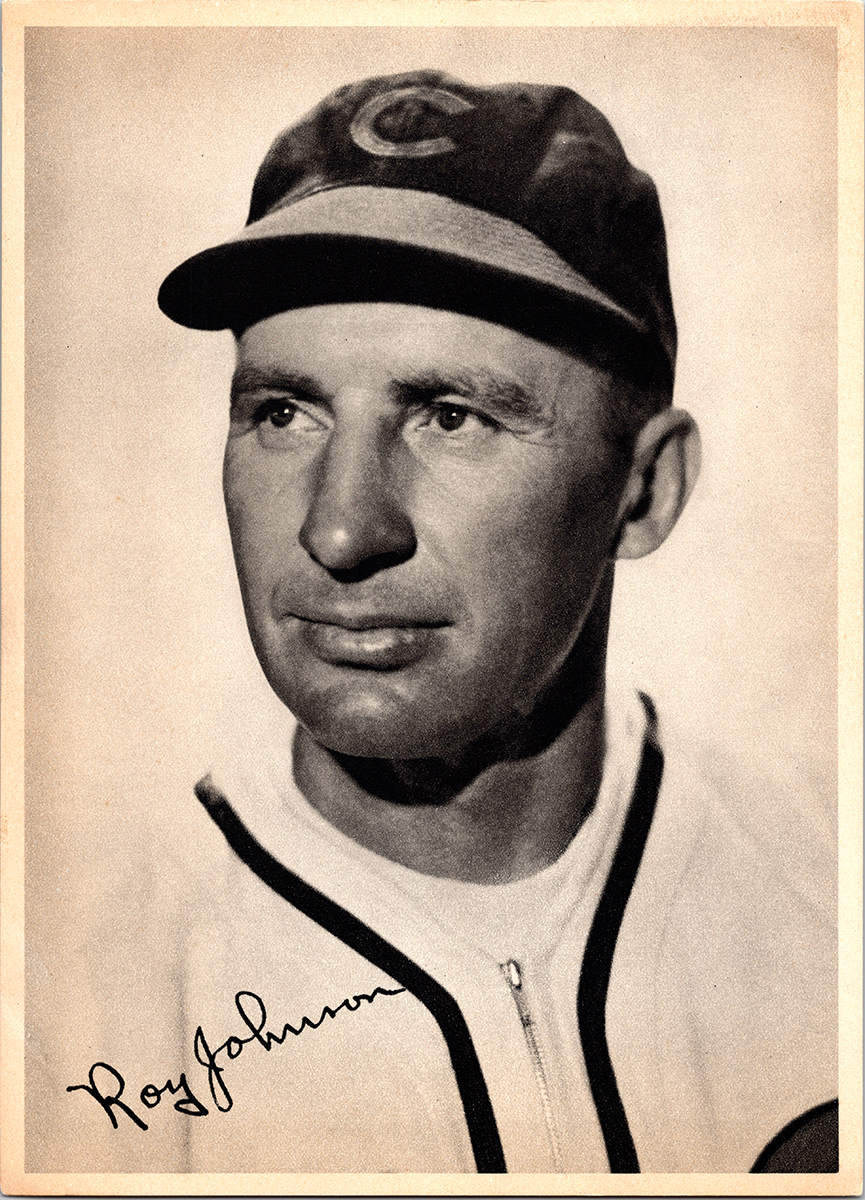

Roy Johnson

Hardrock Johnson: it’s one of the great tough-guy names. Roy Johnson got the monicker as a minor-league manager in Arizona, circa the late 1920s, because “he was a stickler for hard playing.”1

Hardrock Johnson: it’s one of the great tough-guy names. Roy Johnson got the monicker as a minor-league manager in Arizona, circa the late 1920s, because “he was a stickler for hard playing.”1

Johnson, a righty pitcher, was in the majors for part of just one season, 1918. He posted a 1-5 record in 10 games for the Philadelphia Athletics, who finished in the American League’s cellar that year. However, he spent nearly 70 years in professional baseball, starting in 1915. Johnson got his start as a manager in “outlaw” leagues in the mid-1920s after bouncing around those circuits and Organized Baseball as a hurler. He then became a minor-league skipper for 10 seasons and a big-league coach for 15 more. In 1944, he was the interim manager of the Chicago Cubs for one game.

Starting in 1953, Johnson was also a scout for over 30 years. After he died in 1986 at age 90, his widow said, “Roy loved to work. He was going out and sitting in a beach chair to scout high school and college games until just a year or so ago.”2

* * *

Roy J. Johnson – it’s not known what the middle initial may have stood for – was born in Madill, Oklahoma on October 1, 1895.3 Madill was in what was then the Chickasaw Nation – Oklahoma did not become a state until 1907. Roy was the eldest of three children born to Albert C. and Sally Doshia (née Pennington) Johnson, fondly known as “Red” and “Doshie.” He was followed by two sisters, Lilly and Gloe.4

Ira Berkow of the New York Times wrote a warm reminiscence of Johnson that appeared after the old baseball man’s death. One passage recounted, “To avoid becoming a coal miner like his father, Roy first became a prize fighter. It wasn’t long before he understood that this was as tough a way to earn a living as digging coal, and turned to baseball, and pitching.”5

Johnson began his professional career at age 19 with the McAlester (Oklahoma) Miners of the Western Association (Class D). This club was located about 13 miles northwest of Haileyville, the coal town where Johnson grew up. In 29 games, he was 6-10 with a 3.41 ERA. Like many young pitchers, he lacked control, walking 96 in 153 innings pitched. Indeed, according to a report from March 1917, “he had all the stuff in the world … but [was] farmed out on account of wildness.” Thus, he spent 1916 in another Class D circuit, the Central Texas League. With the Terrell Terrors, he posted marks of 2-7, 3.86. He cut his walks down to 34 in 77 innings.

By the time the 1916 season started, Johnson was a married man. His wife, Fanetta (née Aubuchon) was also from Haileyville. They got hitched there on March 306 and remained together for nearly 70 years. The couple had one daughter, Joan.7

Johnson returned to McAlester for the 1917 season. Although Baseball-Reference.com does not have mound stats for him that year, contemporary press noted that he did “some brilliant pitching,” including two no-hitters. Thus, that September the New York Giants of the National League acquired him in the minor-league draft.8 A couple of later articles suggest that Johnson was with the Giants for the tail end of the 1917 season, but the bulk of the evidence indicates that he was not.

As the 1918 season dawned, the Kansas City Blues of the American Association (Class AA) formed a working agreement with Giants manager John McGraw. The Blues obtained several players who were deemed in need of more experience before they could earn jobs with the Giants.9 The available numbers for Johnson with K.C. that year are patchy – a 6-7 record without ERA – but clearly, he continued to attract attention at the top level. A July 31 report out of St. Louis stated that Cardinals president Branch Rickey had signed Johnson and that the hurler would join the Cards in the east.10

Within a week, however, Johnson had joined the Philadelphia A’s. Either the St. Louis deal fell through or A’s boss Connie Mack offered more attractive terms. The Philadelphia Inquirer reported on August 8 that the pitcher had been “picked up by Mack as a free lance.”11 Five days later, the Washington Herald called Johnson “a youth obtained from the Kansas City club when Mack was on the Western tour.”12

The rookie made his big-league debut on August 7 in the opener of a doubleheader at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis. He allowed just four hits in eight innings but lost, 3-1. The Inquirer observed that “passes simply donated the first matinee to the Browns.”13 Johnson issued eight walks, including two in the fourth that followed three of the St. Louis hits.

His second outing, on August 12 at Shibe Park against Washington, was another eight-inning complete game. The Herald said, “he made a neat job of it,” noting that the one Senators run he allowed was unearned.14 The game was called after the eighth with the score tied at 1-1.

Johnson lost again to the Browns on August 14, giving up three unearned runs after entering in relief in the 11th. From August 16 through August 27, he made four starts, losing two and getting no decision in the others.

On Friday, August 30, Johnson appeared in both ends of a doubleheader at Fenway Park in Boston. The first, as a starter, gave rise to an anecdote about facing Babe Ruth, then in transition to becoming a full-time outfielder. According to Johnson’s widow, Mack said to Johnson, “This guy can hit. Don’t give him anything. Make him bite. Or walk him if you have to.” She continued, “Roy threw and the Babe hit the ball 400 feet into the last row of the bleachers. Roy said, ‘It might have cleared the Bunker Hill monument, but at least I didn’t walk him.’”15

Like many such tales, though, this one was embellished. The records show that Johnson did not allow a homer in his 50 innings pitched in the majors. He did, however, give up a two-run double to Ruth that brought in Boston’s first two runs in a 12-0 romp. Johnson was removed after two innings and took the loss.

Three days later, Johnson got into the win column, going all the way at Griffith Stadium in Washington. He walked seven but gave up just six hits; the final score was 5-2. That turned out to be Johnson’s last outing in the majors – he was just 22.

After spending the 1919 season and early 1920 back in Kansas City, Johnson jumped to an “outlaw” team in Idaho Falls, Idaho.16 He started 1921 with another independent club, this one in Logan, Utah – but left for Denver in the Midwest League in late May.17

Johnson spent 1922 with at least three different teams: one in Osawatomie (Kansas), another in Pontiac (Illinois), and a third in Racine (Wisconsin).18 None appears to have been in Organized Baseball. The next year, he worked with a club representing Nash Motors of Kenosha (Wisconsin)19 and a squad in Jackson (Tennessee).20

Johnson applied for – and was granted – reinstatement to Organized Baseball in 1924.21 The Oklahoman returned to the Sooner State and split 1924 between Oklahoma City and Tulsa of the Western League (Class A). He was with Tulsa again in 1925, as well as Danville (Illinois) of the Three-I League (Class B).

Stepping out of the O.B. realm again in 1926, Johnson took his first managerial assignment with Fort Bayard (New Mexico) of the Copper League. Fort Bayard won the pennant, and Johnson returned for the 1927 season.22

The Arizona State League was organized in 1928, and the Bisbee club hired Johnson as manager. He spent five seasons as the Bees’ skipper; for the last two (1931 and 1932), the franchise was in the Arizona-Texas League. Johnson still made occasional appearances as a player – but it was as a manager during this time that he earned his enduring nickname. He told his friend, author Ed Howsam, the story in his own words in the 1980s.

“We were playing down in Tucson and I got run out of the ball game. They put me out of the ball park and there stood a big gray horse with a saddle on it that someone had tied to a hitching post. So I got on this old gray horse and rode him up to the fence just to where I could see real good. I sat there on him and no one paid any attention to me, so I managed the game from on top of that horse.

“Finally, the umpire spotted me and got me off the horse. The next day, Pop McKale [a fixture for decades in University of Arizona athletics] – he did a little sportswriting in the summer in those days – had quite a write-up. About how our club … had to hustle for that old hardrock manager. The kids began to call me Hardrock and when I went to the big league as a coach everyone called me Hardrock.”23 In addition, “hardrock” is a term from mining, which was the backbone of the Bisbee economy. By one account, Johnson was a hardrock miner himself in Bisbee in the offseasons.24

Mired in the depths of the Great Depression, the Arizona-Texas League folded midway through the 1932 season.25 Johnson may not have been in baseball in 1933. He returned to managing in his native state in 1934 with the Ponca City Angels of the Western League (Class C). The Angels were an affiliate of the Chicago Cubs, and Johnson would be employed by that organization for more than half a century.

Johnson moved up to become the big club’s pitching coach in 1935. He remained in that role through the 1939 season. The Cubs won pennants in two of those five seasons, 1935 and 1938; their pitching staff included various fine hurlers, among them Lon Warneke and Bill Lee.

From 1940 through 1942, Johnson was back in Oklahoma once again, managing the Tulsa Oilers, the Cubs’ farm team in the Texas League (Class A). Most of the press attention he received during this time was from 1940, when the Oilers featured Dizzy Dean, then aged 30 and continuing to battle arm problems – but still a big name. Dean pitched well enough in Tulsa to get another chance with Chicago that September.

With World War II in full swing, the Texas League did not operate from 1943 through 1945. Thus, for the 1943 season, Johnson stepped down to Class D ball as skipper of the Lockport (New York) Cubs in the PONY League. His charges included three future big-leaguers, the most notable being Jim Delsing.

Johnson returned to the big club in Chicago as pitching coach in 1944. “The announcement was a popular one,” The Sporting News observed, “with those who know of Johnson’s tireless energy and his constant eagerness to help youngsters improve themselves.”26

After winning on Opening Day, the team dropped nine in a row, and manager Jimmie Wilson quit on May 1.27 Johnson’s one game as a big-league skipper came on May 3 at Wrigley Field; the Cincinnati Reds beat the Cubs, 10-4. He would have had more to show for his interim stint if bad weather hadn’t interrupted the homestand at Wrigley for the next three days.28 Chicago then named Charlie Grimm manager.

Johnson resumed his duties as pitching coach, remaining in that role through the 1950 season (he also served as first base coach). The Cubs won the NL pennant in 1945, and the team’s top winner that year – Hank Wyse (22-10) – gave Johnson credit for “aiding in the development of his rubber arm.” Johnson, who had been Wyse’s manager at Tulsa in 1940-42, “stressed the theory that an arm can be strengthened only by constant throwing and insisted on [Wyse’s] working frequently in batting practice and pepper games.”29

That same year, Johnson also helped the team’s primary shortstop, Lennie Merullo, with a hitting tip – just to try to meet the ball, not kill it. That advice came while Johnson was throwing batting practice.30 Johnson also observed that the other half of the Cubs’ double-play combo, second baseman Don Johnson, worked well with Merullo “because they teamed together for me at Tulsa. They know each other’s every move.”31

An entertaining description of Johnson in the clubhouse appeared during the pennant race late that September, after the Cubs had won a key game over second-place St. Louis to widen their lead to 2½ games. The “celebrated singing duo” of Johnson and Lon Warneke (in his last season as a player) broke into the team’s victory march, “John, the Baptist,” as they did after every win. The team then partook from a waiting tub of beer.32

At age 50 in 1946, Johnson still pitched batting practice almost daily. That August 18, he suffered a broken jaw when he was struck by a Peanuts Lowrey liner.33 After he was discharged from the hospital, he was permitted to go home for the remainder of the season.34 It appears that Hardrock toughed it out and stayed with the club, though, because he was in charge for the last two games of a road trip while Charlie Grimm visited a gravely ill old friend.35 The Cubs split those games at the Polo Grounds on September 18 and 19, beating the Giants 4-3, then losing 1-0.

The great pitcher Robin Roberts had a Johnson anecdote from 1948, Roberts’ rookie year. The backdrop: a game between the Phillies and Cubs (the opener of a doubleheader at Wrigley on July 18) was tied 2-2 in the bottom of the ninth. Chicago had runners on third and first with two outs, but “then for some unknown reason I got wild. I plunked Phil] Cavarretta in the midsection to load the bases and then on the very next pitch hit Andy] Pafko in the ribs to force in the winning run.

“So my first start in Wrigley Field ended in disaster. As I started walking to the dugout with the game over, Pafko, who was upset because I’d hit him, acted like he was going to charge the mound. The Cubs’ first base coach was a tough character called Hard Rock [sic] Johnson. He grabbed Pafko by the shirt and said, ‘You dumb SOB, he wasn’t throwing at you, he just lost the game.’” Years later, according to Roberts, Chicago columnist Mike Royko called Pafko’s move one of the dumbest things he’d seen in his life.36

Charlie Root, who’d been a pitcher for the Cubs during Johnson’s first stint as a coach, became the team’s pitching coach in 1951. However, Johnson remained on the staff. That summer he encountered Ira Berkow, then an 11-year-old autograph seeker, after a game at Wrigley. Berkow described Johnson as “a leathery man, gruff-looking but with a pigeon-toed walk that seemed to suggest a vulnerability below the tough exterior.” Indeed, though Johnson was in a hurry and couldn’t sign that day, he soon made good on his promise to give young Berkow a ball. It became the future sportswriter’s prize possession. But beyond that, Berkow wrote, “Through the years the incident of getting that baseball from Hardrock Johnson stayed with the boy. It enlarged possibilities for him.”37

Johnson coached with the Cubs through the 1953 season. He shifted to the scouting department in October 1953, in part because arthritis was bothering him. (According to Berkow, he had been struck by a baseball and suffered from a bad hip.38) However, the move was part of a broader housecleaning after Chicago had finished in seventh place.39

Despite his change in role, and arthritis notwithstanding, Johnson remained active on the field for the Cubs in spring training 1954. Specifically, he drilled star-to-be Ernie Banks, who’d made his big-league debut the previous September. “Banks was applying himself at shortstop … taking ground balls by the hour from Roy Johnson.”40

Johnson’s territory as a scout was the Southwest and West. SABR’s Scouts Committee credits him with recommending or signing the following major-leaguers (note that some of these players’ careers predated his 1953 reassignment):

- Dick Aylward41

- Jim Brewer

- Eddie Carnett42

- Don Kaiser

- Steve Mesner43

- Dee Moore44

- Ron Santo (shared credit)

The list is surprisingly short but reflects Johnson’s duties. He held the title Special Assignment Scout for the Cubs from 1961 to 1964 and Advance Scout from 1965 to 1982, which would account for his not being credited with signing more amateur prospects. Santo, who became a Hall of Famer in 2012, was the most distinguished of this group. Yet as he related in his 2005 memoir, he signed with the Cubs in 1959 despite the organization’s lowball offer of a $20,000 bonus, which Johnson conveyed.45

A vivid description of Johnson as a scout in the early ’80s forms the first chapter of Baseball Graffiti (1995). Ed Howsam – son of baseball executive Bob Howsam – became a scout himself and learned much from Johnson. He recounted Hardrock’s memories from his decades in the game and his approach to scouting (backed by his companion, a large brown French poodle named Jacques who seemingly had instincts for the real prospects).46

Roy “Hardrock” Johnson died on January 10, 1986. He had been living in a nursing home in Scottsdale, Arizona with his wife, Fanetta. That April, Ira Berkow’s article appeared in the New York Times. It featured his chat with Fanetta, who had shared her memories in a clear voice.

She noted, “Most people called him ‘Grumpy,’ including me and our daughter and even our grandchildren. But living with Roy was wonderful. We just laughed. We had the best time our whole 70 years together. He had that grumpy look, and sometimes his temper was short [Howsam also mentioned his short fuse], but usually it didn’t mean anything.”47

Ed Howsam provided a fitting epitaph for his longtime friend and mentor. “He was every inch a man, a man with true grit, and because baseball was his passion and his life’s work, the consummate baseball scout.”48

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Gregory H. Wolf and Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Rod Nelson.

Thanks to the following for their contributions:

Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee

SABR members Paul Proia and Wayne McElreavy

Eric Costello

Sources

Ed Howsam’s Baseball Graffiti (self-published, 1995) is available online at Internet Archive (archive.org).

Notes

1 Baseball Register, St. Louis, Missouri: C.C. Spink & Son (1952): 252.

2 Ira Berkow, “Sports of the Times: Mr. Hardrock, Sir,” New York Times, April 5, 1986: Section 1, 47.

3 According to The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture (https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=MA004), Madill was founded in 1900. Johnson’s birthplace may have been in the locale that subsequently was named Madill.

4 1910 US Census data, Findagrave.com and various articles from Oklahoma newspapers (The Hartshorne Sun, The M’Alester News-Capital, and The Pittsburg County Republican).

5 Berkow, “Mr. Hardrock, Sir.”

6 Roy and Fanetta Johnson’s marriage certificate.

7 Roy J. Johnson obituary, Arizona Republic, January 12, 1986: 17.

8 The Daily Oklahoman, September 21, 1917: 12. “Johnson Will Play,” Evansville (Indiana) Journal, February 27, 1918: 6.

9 Indianapolis News, April 11, 1918: 18.

10 “Pitcher Roy Johnson Is Signed by Rickey,” St. Louis Star and Times, July 31, 1918: 13.

11 Philadelphia Inquirer, August 8, 1918: 12.

12 Washington Herald, August 13, 1918: 6.

13 See note 11.

14 See note 12.

15 Berkow, “Mr. Hardrock, Sir.”

16 “Skips to Outlaws,” Birmingham News, June 1, 1920: 9.

17 “Roy Johnson Leaves Logan for Denver Club,” Salt Lake Tribune, June 1, 1921: 14.

18 Kansas City Times, May 9, 1922: 10. The Journal Times (Racine, Wisconsin), February 14, 1923: 10.

19 The Journal Times, May 7, 1923: 12.

20 The Commercial Appeal (Memphis, Tennessee), June 10, 1923: 39.

21 Arizona Republic, August 4, 1928: 11.

22 See note 21.

23 Ed Howsam, Baseball Graffiti, Scottsdale, Arizona, EH Productions (1995): 5.

24 Hadley Hicks, So You Wanna Be a Legend. So Did I., Bloomington, Indiana: WestBow Press (2010): 85. Hicks, who was Johnson’s godson, played one season of Class D ball thanks to Johnson.

25 Benedict Carter, Copper City Baseball, Bisbee, Arizona: self-published (2016): 14.

26 Ed Burns, “Cubs Stock Up on Coaches in Johnson, Stock,” The Sporting News, December 23, 1943: 2.

27 Ed Burns, “Wilson Quits, Roy Johnson Bossing Cubs,” The Sporting News, May 4, 1944: 9.

28 Edgar Munzel, “Grimm Called by Cubs, but Gremlins Linger, Too,” The Sporting News, May 11, 1944: 4.

29 “Johnson, Davis Credited in Development of Wyse,” The Sporting News, July 26, 1945: 5.

30 Edgar Munzel, “Merullo’s About-Face at Shortstop Made Him Pivot Man in Cubs’ Rise,” The Sporting News, August 16, 1945: 6.

31 Gene Kessler, “Cubs’ Coaches Find Gems – Polish ’Em,” The Sporting News, October 4, 1945: 16.

32 Edward Prell, “Cubs Celebrate Big Victory with Beer, Banter, Ballads,” Chicago Tribune, September 26, 1945: 25.

33 Edgar Munzel, “Cubs’ Fortunes Continue Bad, Except at Turnstiles,” The Sporting News, August 28, 1946: 9.

34 “Roy Johnson’s Jaw Fractured,” The Sporting News, August 28, 1946: 14.

35 “Grimm Visits Ill Friend,” The Sporting News, September 25, 1946: 6.

36 Robin Roberts with C. Paul Rogers III, The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant, Philadelphia: Temple University Press (1996): 91. The story was retold in the same words in Robin Roberts with C. Paul Rogers, My Life in Baseball, Chicago: Triumph Books (2003): [page number unavailable online]. It has not been possible to pinpoint the Royko column Roberts cited.

37 Berkow, “Mr. Hardrock, Sir.”

38 Berkow, “Mr. Hardrock, Sir.”

39 Edgar Munzel, “Cubs Spare Cavvy but Lower Boom on Coaching Staff,” The Sporting News, October 14, 1946: 24.

40 Ron Rapoport, Let’s Play Two, New York: Hachette Books (2019): [page number unavailable online].

41 Aylward played for Johnson in Lockport in 1943. He made it to the majors with Cleveland in 1953.

42 Carnett went to Ponca City High School and was signed by the Cubs in 1935. He first reached the majors in 1941 with the Boston Braves.

43 Mesner played for Johnson at Ponca City in 1934.

44 Moore also played for Ponca City in 1934 but signed his first contract with the Cubs in 1933.

45 Ron Santo with Phil Pepe, Few and Chosen, Chicago: Triumph Books (2005): xv.

46 Howsam, Baseball Graffiti: 1-8.

47 Berkow, “Mr. Hardrock, Sir.”

48 Howsam, Baseball Graffiti: 8.

Full Name

Roy J. Johnson

Born

October 1, 1895 at Madill, OK (USA)

Died

January 10, 1986 at Scottsdale, AZ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.