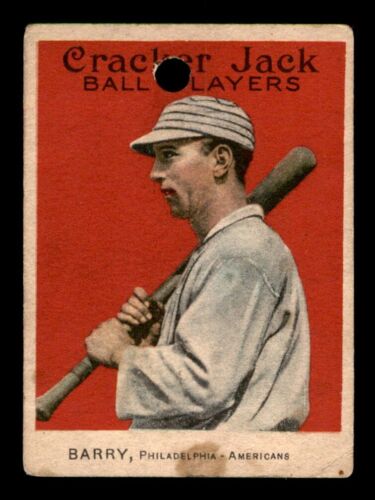

Jack Barry

The least known member of the Athletics’ famous $100,000 infield, Jack Barry was a .243 career hitter with little power and average speed, who nonetheless earned the respect and admiration of his peers because he did the so-called “little things” well: pulling off the squeeze play, turning the double play, and hitting in the clutch, among others. Playing in an era that espoused the virtues of the “inside” style of play, the quiet, brainy shortstop was thought by many teammates, opponents, and writers to be the most valuable member of Mack’s famous infield. As Philadelphia Inquirer writer Edgar Wolfe (writing under the nom de plume Jim Nasium) put it in 1913, “Barry is the weakest hitter of the quartet, but his hits are always timely and his sensational fielding is something that cannot be computed in cold, soulless figures.” Ty Cobb once called him the most feared hitter on the A’s, and Hughie Jennings declared that “I’d rather have Barry than any .400 hitter in the business. . . In a pinch he hits better than anybody in our league outside of Cobb.”

The least known member of the Athletics’ famous $100,000 infield, Jack Barry was a .243 career hitter with little power and average speed, who nonetheless earned the respect and admiration of his peers because he did the so-called “little things” well: pulling off the squeeze play, turning the double play, and hitting in the clutch, among others. Playing in an era that espoused the virtues of the “inside” style of play, the quiet, brainy shortstop was thought by many teammates, opponents, and writers to be the most valuable member of Mack’s famous infield. As Philadelphia Inquirer writer Edgar Wolfe (writing under the nom de plume Jim Nasium) put it in 1913, “Barry is the weakest hitter of the quartet, but his hits are always timely and his sensational fielding is something that cannot be computed in cold, soulless figures.” Ty Cobb once called him the most feared hitter on the A’s, and Hughie Jennings declared that “I’d rather have Barry than any .400 hitter in the business. . . In a pinch he hits better than anybody in our league outside of Cobb.”

John Joseph Barry was born April 26, 1887 in Meriden, Connecticut, the oldest child of Patrick and Mary Doohan Barry, natives of County Kerry, Ireland. Patrick Barry owned a saloon, and his family lived atop an incline at 24 Hillside Avenue. There was a barn on the corner of the property, and young Jack developed his speed and agility by throwing a ball over the barn roof and dashing around to the other side to catch it on the way down.

Jack attended St. Rose parochial school and Meriden High, where his team twice won the state championship. His infield play prompted local Holy Cross athletic boosters to arrange for him to attend Holy Cross prep school, a division of the College of the Holy Cross. He arrived in the fall of 1902 and played every infield position during his two years at the prep school and four years at the College. By the spring of 1908 a half dozen major league teams were eager to sign the Holy Cross senior. The White Sox asked Meriden’s most prominent citizen, Ed Walsh, to talk to him. They were all too late. Connie Mack’s brother, Tom, a hotel owner in Worcester, had kept his brother informed about Barry since 1905. In the fall of 1907 Tom had invited Barry to meet the Athletics’ manager at the hotel. At the meeting Barry asked for a $500 signing bonus. Mack agreed, but asked Barry not to say anything about it, as it was not his policy to pay such bonuses. (Barry never mentioned it outside his family.) Barry signed a 1908 contract, and joined the A’s in June after the college season ended.

Jack Barry proved to be Connie Mack’s kind of player: quiet, smart, hardworking, innovative, straight-arrow, a non-drinker until later in life. He went to Mass every morning. At first Mack intended to keep the 21-year-old rookie on the bench beside him, teaching and bringing him along slowly. But he needed a second baseman one day and put Barry in the lineup. For the rest of the year the 5’9″, 151-pound Barry played second, short and third before Mack decided that shortstop was his best position.

Barry was the second member, after Eddie Collins, to arrive in what many called the greatest infield ever assembled. Despite dissimilar personalities, Collins and Barry became lifelong friends. Given a free hand by Mack, they worked out plays that no other keystone combination could approach. Together they perfected a defense against the widely-used double steal, in which the weaker-armed Collins cut in front of second, stopped the catcher’s throw if the runner on third broke for home, or ducked and let it go through to Barry if the runner stayed near third. Chicago sportswriter Hugh Fullerton also believed that Barry was the best in the game at taking throws, blocking the base and holding runners close to second.

Barry’s enormous range enabled third baseman Frank Baker to play close to the line at third and Collins to shade toward first, even with a man on first and a potential double play in sight. His ability to cover second from deep in the hole at short and take throws from Baker, then relay to first for double plays, drew comments of amazement from the likes of shortstop Bobby Wallace. Also known for his sure hands, Barry cut a cross clear through the palm of the small, short-fingered glove he favored for digging out ground balls, using the sweat from his hand to help him grip the ball.

At the plate, the weak-hitting Barry was overshadowed by his more famous teammates, as he hit with little power and never batted better than .275 in a single season. But the same headiness that Barry brought to his play in the field, he carried with him into the batter’s box, where the right-hander developed a reputation among his peers as one of the league’s most dangerous clutch hitters. “If Barry’s batting average was only .119 and a hit was needed to win a game for the Athletics, it’s a cinch that 99 percent of the fans would rather have Barry at bat than any other man on Mack’s payroll,” Stony McLinn of the Philadelphia Press observed. An exceptional bunter, Barry was free to call a squeeze play on his own, and was the only man in the lineup who was trusted to call the double squeeze — scoring men from second and third on a bunt. It almost always worked.

Beginning in 1910, the Athletics won four of the next five pennants and three World Series. Summaries of these Series never single out Barry, but baseball people knew better. In 1910 against the Cubs, Collins batted .429, Baker .409, Barry .235. But several members of the Cubs said it was Barry who beat them with his glove, and Cubs manager Frank Chance called him the best shortstop he had ever seen, including Honus Wagner. And despite Baker’s heroics in the 1911 World Series, the four umpires who worked the games picked a Barry play that looked routine to the crowd as the best of the Series.

Following the A’s sweep at the hands of the Braves in 1914, Mack did not expect the team to go from first to last in a hurry, even though he sold Collins during the offseason. But Frank Baker held out for the entire 1915 season, and by July 1 the A’s had sunk into the cellar. Once Mack made the decision to cut his losses and sell Barry, several teams expressed their interest. The Yankees, Red Sox, and White Sox all wanted him, but Barry preferred to play near his home, so Mack sold him to Boston, where he played second base, a position he considered a snap compared to shortstop. Barry would play only a single inning at short over the rest of his career.

Thanks in part to Barry’s stabilizing influence on the Boston infield, the Red Sox won back-to-back World Championships in 1915 and 1916, making Barry the first player in history to win four World Series. When Bill Carrigan resigned as the Red Sox manager after the 1916 season, Barry replaced him. The only player-manager in the league, he piloted Boston to a second-place finish in 1917.

With the United States’ entry into World War I, Barry joined the Naval Reserve before the end of the 1917 season. In November, he was called up as a yeoman at the Charlestown Navy Yard in Boston, where he ran track and managed the baseball team. He was promoted to a school for ensigns, and after missing the entire 1918 season, he was discharged in December. In his absence Barry had lost his managerial job to Ed Barrow and his second base job to Dave Shean, so in June 1919 the Red Sox traded him back to the Athletics as part of a four-man deal. Though still just 32 years old, Barry’s legs and knee, injured in the Navy and abused throughout his 11-year-career, felt more like 50. After weeks of mulling it over, Barry retired from baseball.

Following his retirement, Barry and his wife, the former Margaret McDonough, moved to Shrewsbury, Massachusetts, near Worcester, where Barry had helped coach the Holy Cross baseball team since 1912. In 1921 he became the Crusaders’ full-time coach, and stayed for 40½ seasons, compiling a record of 619-147; his .806 winning percentage remains the best in baseball history. His team was unbeaten in 1924, and College World Series champions in 1952. He sent 29 players to the major leagues. In 1956, he became one of the first six inductees into the Holy Cross Hall of Fame.

At home in Shrewsbury, Jack Barry played rummy and poker, and was a member of the Knights of Columbus. A self-taught piano player, he enjoyed hitting the keys after Sunday dinner, singing, “Margie” for his wife, and “Take Me Out to the Ball Game,” where it was “root, root, root for the Red Sox.”

Jack Barry passed away in his home from lung cancer on April 23, 1961, three months after his 50th wedding anniversary and three days before his 74th birthday. Survived by his wife, he left behind no children. He is buried at Sacred Heart Cemetery in Meriden. A square is dedicated to him in Shrewsbury.

Note

This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

For this biography, the author used a number of contemporary sources, especially those found in the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Full Name

John Joseph Barry

Born

April 26, 1887 at Meriden, CT (USA)

Died

April 23, 1961 at Shrewsbury, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.