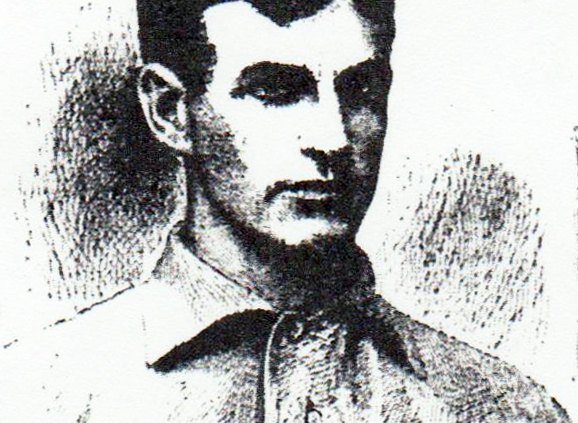

Jack Fifield

Right-hander Jack Fifield faced a challenge familiar to second-line pitchers in the late 19th century: getting out major league batters with a mediocre hurling repertoire. Still, he managed to eke out three full big-league seasons before dropping down to a more congenial competitive level. Pitching for the Syracuse Stars, Fifield was the Class B New York State League’s premier hurler for several seasons, with accomplishments that eventually led to his enshrinement in the Syracuse Baseball Wall of Fame. Northern New England native Fifield also made Syracuse his home during the offseason and beyond, living and working there until his passing in November 1939. The ensuing paragraphs recall this now-distant life.

Right-hander Jack Fifield faced a challenge familiar to second-line pitchers in the late 19th century: getting out major league batters with a mediocre hurling repertoire. Still, he managed to eke out three full big-league seasons before dropping down to a more congenial competitive level. Pitching for the Syracuse Stars, Fifield was the Class B New York State League’s premier hurler for several seasons, with accomplishments that eventually led to his enshrinement in the Syracuse Baseball Wall of Fame. Northern New England native Fifield also made Syracuse his home during the offseason and beyond, living and working there until his passing in November 1939. The ensuing paragraphs recall this now-distant life.

John Proctor Fifield was born on October 5, 1871 in Enfield, New Hampshire, a quiet Upper Connecticut River Valley town located about 10 miles east of the border with Vermont.1 He was the youngest of seven children2 born to produce and livestock trader Andrew Chauncey Fifield (1832-1889) and his wife Sylvia (née Proctor, 1834-1921), both descended from WASP forebears whose New Hampshire roots predated the Revolutionary War. Jack (as he was commonly called) was educated locally until his enrollment in Proctor Academy, a college prep school located in nearby Andover and named for generous school benefactor John Proctor (1804-1883), our subject’s granduncle. He subsequently matriculated to prestigious Dartmouth College and graduated in 1891.3

A Fifield profile published in the New York Clipper includes the unenlightening observation that he “learned to play ball at an early age.”4 Apart from that, little is known about Fifield’s youthful athletic pursuits – the claim that he played football and/or baseball at Dartmouth finds little support in the historical record.5 An obituary maintains that after college graduation Fifield began his working life in the employ of the Boston & Maine Railroad and that during this time he pitched for a YMCA team in Concord, the Granite State’s capital.6 He also reportedly played ball in the independent New Hampshire League.7

More certainly established is the fact that Fifield entered the professional ranks in 1895, signing with the Little Rock (Arkansas) Travelers of the Southern League.8 When not in the box for the Travelers, Fifield, a natural athlete, was deployed around the diamond, playing infield, outfield, and even catching on occasion.9 But he took his lumps pitching, with enemy hitters pounding him for a .346 opponents’ batting average. And he got little help from his defense, with more than half the runs scored against him (83 of 164) being unearned.10 Despite that, Fifield had managed to post seven victories by the time that the last-place (25-47, .347) Little Rock club folded in late July. He was “considered by many to be the star pitcher of the Southern League.”11

That reputation apparently intrigued veteran Chicago Colts playing manager Cap Anson, who signed the newly available prospect for his pitching-thin National League club.12 Fifield, however, never received a shot in a regular season game with Chicago before being released to the Detroit Tigers of the top-tier minor Western League.13 In a late-season audition, he was again hit hard, surrendering better than a run per inning and posting an unimpressive 1-4 (.200) record in six outings for the Tigers.14 But his press reviews were nonetheless glowing: Sporting Life’s local correspondent gushed, “young Fifield will be [Detroit’s] mainstay next season. He is the absolute master of the in-shoot that no batsman can get next to. With a month’s campaigning he will round to as an invincible.”15

In 1896, Fifield’s performance vindicated his press admirer’s improbable prediction. He started fast, downing Indianapolis in Detroit’s opener, 6-4. Later in the campaign, he notched complete-game victories in both ends of a doubleheader against Indianapolis.16 The righty-swinging Fifield was also reportedly the first player ever to hit a fair ball over the fence at Detroit’s Bennett Field.17 By season’s end, he was one of the Western League’s best pitchers, having gone 28-13 (.683)18 with a sharp 2.66 ERA19 in 47 outings for player-manager George Stallings’ third-place (80-58, .580) Detroit club.

Fifield’s work did not go unnoticed by major league teams. Sporting Life declared that “the only Western League twirler that is absolutely certain to go [up] is at present young Fifield, the great twirler of the Detroit club. Fifield will pitch in the National [League] in ’97 without a doubt.”20 Shortly thereafter, the Philadelphia Phillies purchased Fifield’s contract for a reported $1,500.21 Accompanying Jack to his new team was Detroit skipper George Stallings, engaged as the Phillies manager.22 Stallings was another enthusiastic Fifield booster, informing the press that the Phillies’ acquisition “was a wonder in pitching and the best fielder in his position in the profession. … [I]n fact he is in a class by himself as a pitcher and general player, being able to play well in any position, even behind the bat.”23

As a rookie, Fifield proved unable to live up to his advance billing. Lightly framed (5-feet-11 and 160 pounds), he did not possess overpowering stuff. His pitching arsenal – a tailing fastball and a variety of curves – was found eminently hittable by major league batsmen, and his strikeout-to-walks ratio would always be poor. But Fifield had poise and intelligence; decent control; pitched to contact effectively, if not consistently; and capably fielded his position. The 25-year-old hurler made his major league debut on April 28, 1897, pitching “a masterly game” against the Boston Beaneaters, but losing 6-5, undone by his own uncharacteristic defensive miscues in the late going.24 Notwithstanding the result, the Philadelphia Times was favorably impressed, reporting that “Fifield pitched a good game. … He showed a tendency to nervousness when men were on base and was a little wild, but should prove a winner for all.”25 The Philadelphia Inquirer felt the same way, stating that “Fifield reminds one of [Charlie] Buffinton. ‘Jack’ showed he is made of the proper sort of mettle.”26

Fifield dropped his next two starts before breaking into the major league win column on May 14 with a five-hit, complete-game triumph over Louisville, 7-1. But follow-up victories were hard to come by. At season’s end, his record stood at an unsightly 5-18 (.217) – he’d surrendered 263 base hits and 80 walks (as opposed to only 38 strikeouts) in 210 2/3 innings pitched for a 10th-place (55-77-2, .417) Philadelphia club.

The following season, Fifield made the Opening Day roster but was the forgotten man on manager Stallings’ staff. The campaign was already a month old before the rusty hurler made his first appearance, walking nine and hitting three batters in a 9-5 loss to Baltimore on May 17. He then sat idle for almost two months, taking in 48 consecutive games from the Philadelphia bench. Fifield, however, put this dormant period to at least one useful purpose. In mid-June, he briefly returned to New Hampshire and took Andover resident Ethel Wolfson as his bride.27 In time the arrival of children Margaret (born 1898), John Proctor, Jr. (1904), and George (1905) completed the Fifield family.

In early July, thew newlywed finally saw some playing time – at shortstop for the Phillies reserves. The occasion was a midseason exhibition game against a Port Richmond (Philadelphia) semipro nine, with the Phillies pitching chores being assigned to a novelty act: female hurler Lizzie Arlington. The versatile Fifield registered three hits at the plate and later struck out four in scoreless relief of Arlington.28

By the time that Arlington appeared in a Phillies uniform, manager Stallings was gone, replaced at the helm by Billy Shettsline. The change soon redounded to Fifield’s benefit. Given a July 11 start against Cleveland, the well-rested Fifield posted a 9-3 victory. Two complete-game wins quickly followed. Promoted to the starting rotation, he pitched the best ball of his major league tenure, throwing two shutouts late in the year.29 He finished the season with an 11-9 (.550) record and a respectable 3.31 ERA in 171 1/3 innings pitched. Under Shettsline’s direction, meanwhile, Philadelphia had gone a much improved 59-44-1 (.573) and climbed up to sixth place in final National League standings.

Regrettably for Fifield, he could not repeat the previous season’s success. As in the year before, he did not see action in early 1899, waiting almost three weeks to get his first start. Scattering eight hits, he downed New York, 7-3. Ten days later, he blanked the Giants, 9-0. But thereafter, his record spiraled downward, as he lost six of seven decisions, leaving supportive Sporting Life editor Francis C. Richter to lament that “Fifield seems unable to get out of his losing rut. … Instead of being the Phillies star pitcher … he has changed places with [Chick] Fraser as the team’s losing pitcher.”30

With his record standing at 3-8 (.273) in mid-July, Fifield was optioned to the Minneapolis Millers of the Western League.31 There, he split eight decisions32 before being placed on suspension for “indifferent work”33 or “insubordination”34 and remanded to the Phillies. Given that the quiet, teetotaling Fifield was neither a slacker nor a troublemaker, such explanations for his suspension seem dubious. But whatever the cause, he was back in Philadelphia livery in time to make a relief appearance during an 8-0 loss to St. Louis on August 18. It was obvious, however, that Fifield was no longer a part of the club’s future plans, and he was unconditionally released in early September.35

Hours after Fifield was jettisoned by Philadelphia, he signed with the 11th-place Washington Nationals and promptly beseeched manager Arthur Irwin for that day’s start against his former club.36 The request was granted but he turned in a nightmarish outing, yielding 21 base hits and walking 10 in an 18-10 trouncing by the Phillies.37 A week later, he partially redeemed himself with a route-going win over Cincinnati, 6-3. But thereafter Fifield pitched poorly, finishing the campaign at 2-4 (.333) with an inflated 6.13 ERA in six complete-game starts for the Nats.

During the winter, the bloated and unprofitable 12-team National League was reduced to an eight-club circuit for the 1900 season. A byproduct of NL contraction was unemployment at the major league level for borderline playing talents like Jack Fifield. Although he continued pitching for another nine seasons, Fifield’s time as a big leaguer was over. In 68 games overall, he posted a 21-39 (.350) record, with a high 4.59 ERA in 521 2/3 innings pitched. Over that span, he allowed 616 base hits (yielding a hefty .292 OBA) and walked 193. With only 89 enemy batsmen retired via strikeout, he was constantly dependent on shaky defenses that made nearly one-third of the runs scored against him unearned. Still, he managed to complete 54 of 64 starting assignments and threw three shutouts.

The Washington Nationals were one of the four National League clubs liquidated over the winter, leaving Fifield a free agent but without top-echelon suitors. He was, however, wanted back in Detroit, now a member of the minor American (née Western) League. Shortly before the 1900 season got underway, he signed with the Tigers, once again managed by former mentor George Stallings.38 But Fifield was unable to recapture his sterling 1896 form, being pummeled (35 hits plus 11 walks in 20 innings) in five appearances and losing both his decisions. By late May he had been given his walking papers by Detroit. A subsequent tryout with the AL’s Chicago White Sox was also a bust.39 Thereafter, Fifield returned home and spent the remainder of the summer pitching, with little success, for semipro clubs in New England.40

Fifield reentered Organized Baseball for the 1901 season, signing with the Rome (New York) Romans of the Class C New York State League. Before leaving home, however, he returned to the Dartmouth campus to tutor his alma mater’s pitching prospects.41 Once in Rome, he took a place in the club rotation, appearing in 40 contests; his other pitching stats are not available.42 Fifield’s work, however, was apparently good enough for the club to want him back in 1902.43 But before he returned, a life-changing event occurred: the Rome franchise was transferred to Syracuse.44 Fifield promptly rerouted himself to Syracuse – and never left, spending the remainder of his life there.

Neither Baseball-Reference nor the Reach and Spalding Guides provide particularized pitching stats for the New York State League, elevated to Class B status for the 1902 season. But the press release that accompanied the Syracuse Baseball Wall of Fame induction of the Class of 2004 states that Fifield won 19 games for the fourth-place (61-55, .526) Syracuse Stars. During the offseason, he secured a job managing a local bowling alley, informing the press that he had “not the slightest desire to break into either of the big leagues.”45 That winter he also reportedly managed an indoor baseball club in Syracuse known as the Yale Rifles.46

Fifield was the crème of the pitching crop in the 1903 New York State League, leading circuit hurlers in victories with 26.47 He replicated that feat the following season, going 26-7 (.778), and leading the New York State League in wins and winning percentage48 for the pennant-capturing (91-44, .674) Syracuse Stars of 1904. At season end, he was also chosen the Stars’ most popular player by fans’ vote.49 By now, Fifield had permanently relocated his young family to Syracuse and spent the ensuing winter managing a local ice-skating rink.50

Although his pitching stats are unavailable, it appears that Fifield thereafter went into decline. He posted a losing record in 1905,51 and was around .500 the following year.52 Likewise, there are no pitching data for Fifield’s 1907 season, but he could plainly still be effective on occasion, as reflected in a five-hit, 3-0 shutout of Troy on July 27.53 Fifield was listed on the Syracuse roster for the 1908 campaign,54 but by early May he was pitching for a NYSL rival, the Binghamton Bingos. Although he won some early season games for his new club,55 he drew his release after a poor outing in mid-June.56 He was then signed by another NYSL team, the Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Barons,57 but his stay there was brief, as well.

Released by Wilkes-Barre in mid-July, Fifield applied for a position as a circuit umpire. That application drew a wholehearted endorsement from the Wilkes-Barre Times-Leader, which stated that “Jack is one of the best fellows in League base ball and has a host of friends among both players and fans and the Times-Leader unites with them in wishing him all success.”58 Another local newspaper seconded the sentiment, observing that “Fifield has been one of the best and brainiest pitchers in the State league for years. He is cool and collected under all circumstances and best of all has intelligence and good judgment.”59 NYSL President John H. Farrell promptly approved the application and Fifield spent the remainder of the season in New York State League blue.

After the season, Fifield left baseball to “become the head of the time department at Brown-Lipe-Chapin Company,”60 a Syracuse-based manufacturer of automobile parts. The pull of the game, however, proved irresistible; Fifield took leaves of absence from his company job during the summers of 1913 and 1914 to umpire in the Southern League, the place where he began his professional baseball career some two decades earlier.61 He also coached the baseball team at St. John Military Academy in Manlius, a Syracuse suburb.62

Fifield was a Depression Era employment casualty, being laid off the job at Brown-Lipe-Chapin in 1931, “after which he engaged in no business.”63 His health began to decline in the mid-1930s, and he died of a heart attack suffered at his Syracuse residence on November 27, 1939. John Proctor “Jack” Fifield was 68. Following a local funeral service conducted by a Congregational Church clergyman, the deceased was returned to his native New Hampshire and interred at Proctor Cemetery in Andover. Survivors included his widow Ethel, sons Proctor and George, daughter Margaret Lewis, and two siblings.

Almost a century after he had last worn a Syracuse Stars uniform, the long-deceased Jack Fifield was enshrined in the Syracuse Baseball Wall of Fame. Established in 1998, the Wall of Fame “recognizes individuals who made unique contributions to the history of professional baseball in Syracuse and Central New York, both on the field and off.”64 It honors luminaries such as Grover Alexander, Jim Bottomley, Vic Willis, Thurman Munson, and Pepper Martin. To state the obvious, our subject’s plaque inhabits a distinguished neighborhood.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Darren Gibson and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Jeff Findley.

Sources

Sources for the biographical info imparted above include the Jack Fifield file at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; the Fifield profiles published in the New York Clipper, July 17, 1897, and Major League Player Profiles, 1871-1900, Vol. 1, David Nemec, ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011); US Census and other government records accessed via Ancestry.com; and certain of the newspaper articles cited in the endnotes. Unless otherwise specified, stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

Photo credit: Jack Fifield, New York Clipper, July 17, 1897.

Notes

1 The 1870 US Census placed the population of Enfield at 1,162. Enfield is also the birthplace of Stan Williams (1936-2021), a 14-season major league pitcher.

2 The other Fifield children were Frank (born 1856), Nellie (1857), Susan (1858), George (1859), Everard (1860), and Dell (1868).

3 According to an unidentified obituary contained in the Fifield file at the Giamatti Research Center. Fifield’s TSN contract card also lists him as a Dartmouth graduate, but without the year.

4 “John P. Fifield,” New York Clipper, July 17, 1897: 323.

5 One published report claimed that Fifield played catcher for Dartmouth in 1889 and “was with the collegians for two years.” See “Three Ball Players,” Detroit Evening News, March 15, 1896: 5. But the Fifield name does not appear in the 1887-1891 Dartmouth baseball box scores regularly printed in the Boston Globe and other Northeastern newspapers. Nor is Fifield’s name found on newspaper-published Dartmouth gridiron rosters.

6 Per “J.P. Fifield, Ex Baseball Player, Dies,” unidentified November 27, 1939, obituary in the Fifield file at the GRC.

7 See “Lowell Laconics,” Sporting Life, February 16, 1895: 11.

8 “Baseballists Arrive,” (Little Rock) Arkansas Gazette, March 1, 1895: 6.

9 As established by box scores published in Southern League news outlets.

10 Per Southern League stats published in the 1896 Reach Official Base Ball Guide, 68. Baseball-Reference provides no data for Fifield’s time with Little Rock.

11 “Atlanta Goes Up a Peg,” Atlanta Journal, May 27, 1895: 8.

12 As reported in “Telegraphic Sparks,” Sporting Life, August 1, 1895: 1; “Sporting News,” Arkansas Gazette, July 30, 1895: 2; and elsewhere.

13 As noted in “Diamond Dust,” Milwaukee Journal, September 3, 1895: 8; “Watkins Wants Detroit,” Sporting Life, August 31, 1895: 1; and elsewhere.

14 As established by review of newspaper line scores. Baseball-Reference puts the Fifield log at 1-3 (.250) in six appearances for Detroit.

15 “Detroit Dotlets,” Sporting Life, December 7, 1895: 9. An eastern newspaper was slightly more subdued, stating that Fifield “has made a great hit in Detroit.” See “On the Base Lines,” Boston Herald, September 9, 1895: 10.

16 On August 19, 1896, Fifield posted 5-2 and 7-6 wins. He also went 3-for-7 at the plate with four runs scored during the twin bill.

17 According to “Cronin the Last Word,” Buffalo Sunday Times, August 5, 1900: 10.

18 According to the Jack Fifield profile in Major League Player Profiles, 1871-1900, Vol. 1, David Nemec, ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 64, and “Diamond Dust,” Milwaukee Journal, October 14, 1896: 8. Another source gives Fifield 32 wins. See “John R. Gantry Did It,” Saginaw (Michigan) Evening News, September 25, 1896: 3. Baseball-Reference provides no 1896 stats for Fifield.

19 Per the 1897 Reach Official Base Ball Guide, 28. The Guide does not provide win-loss numbers for Western League pitchers.

20 “Western Players,” Sporting Life, September 19, 1896: 9.

21 As reported in “Sporting Notes,” Decatur (Illinois) Herald-Dispatch, September 27, 1896: 4; “Sammy Gillen a Quaker,” Pittsburgh Post, September 26, 1896: 3; and elsewhere.

22 See “Quakers Finally Secure a Manager,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 2, 1896: 4.

23 “Local Jottings,” Sporting Life, December 19, 1896: 6.

24 See “Sweet Variety Is the Spice of Life,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 29, 1897: 4.

25 “Phillies Lose Their First Game,” Philadelphia Times, April 29, 1887: 8.

26 “Passed Balls,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 29, 1897: 2. Right-hander Charlie Buffinton had notched three-consecutive 20+-win seasons for Philadelphia in the late 1880s.

27 New Hampshire marriage records indicate that the couple wed on June 14, 1898.

28 Per “Miss Arlington Pitched Well,” Philadelphia Times, July 3, 1898: 10. The Phillies distaff starter gave up five runs in four frames before retiring in favor of Fifield. The Phillies Reserves romped, 18-5.

29 On September 19, Fifield blanked Cincinnati, 8-0. Three weeks later, he whitewashed Washington, 6-0.

30 Francis C. Richter, “Phillies Pleasing,” Sporting Life, June 24, 1899: 5.

31 As reported in “Baseball Notes,” Denver Evening Post, July 21, 1899: 10; “Puffs from the Pipe,” Kansas City Journal, July 18, 1899: 6; and elsewhere.

32 As calculated by the writer from published Western League line scores. Baseball-Reference has no Minneapolis stats for Fifield.

33 Per Fifield, Major League Player Profiles, 65.

34 According to “Fourth, Fifth or Sixth,” Detroit Evening News, September 4, 1899: 6.

35 As reported in “News and Comment,” Sporting Life, September 9, 1899: 5.

36 Per “Fifield Makes a Mess of It,” Kansas City Times, September 6, 1899: 3; “Jack Got in Bad,” Columbus Dispatch, September 6, 1899: 9; and elsewhere.

37 Per wire service box scores published in the Boston Globe, Cleveland Leader, and newspapers nationwide, September 6, 1899. Locally published game accounts upped the hit total allowed by Fifield to 23. See e.g., “Base Hits on Tap,” Philadelphia Times, September 6, 1899: 4.

38 As reported in “Harley Signed,” Detroit Evening News, April 10, 1900: 8; “Baseball: Detroit Team Gets Fifield,” Windsor (Ontario) Evening Record, April 10, 1900: 4; and elsewhere.

39 Per “News and Gossip,” Sporting Life, June 23, 1900: 9.

40 Among other places, Fifield pitched for semipro clubs in Newport, Rhode Island, and Bethel, Vermont.

41 Per “Dartmouth’s Squad Out,” Boston Globe, March 5, 1901: 7.

42 Neither Baseball-Reference nor the Reach or Spalding baseball guides provide pitching stats for the 1901 New York State League. Fifield, however, split 16 decisions in the games for which the writer found line scores.

43 Sporting Life, February 22, 1902: 4: “John P. Fifield, the ex-National Leaguer, is working out in East Andover and returns to Rome, NY this season.”

44 Per “New York’s League,” Sporting Life, March 22, 1902: 8.

45 “Another Double-Header Is Forced Upon the Already Hard-Worked Athletics,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 14, 1902: 13. The Fifield stance was probably moot as there is no evidence of any major league interest in the soon-to-be 31-year-old hurler.

46 See “Gathered at Home Plate,” Boston Herald, January 5, 1903: 9.

47 Per the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds. (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 3rd ed., 2007), 191.

48 Per Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, 195.

49 As reported in “New York League Nuggets,” Sporting Life, October 15, 1904: 14.

50 “New York League Nuggets,” Sporting Life, November 19, 1904: 3.

51 Baseball-Reference places Fifield in 30 games during the 1905 season, and by the writer’s reckoning he won only five of the 16 games for which a Syracuse line score was discovered.

52 Fifield appeared in 33 games for the 1906 Syracuse Stars. By the writer’s count, he went 9-10 (.474) in contests for which a line score was found.

53 According to the Class of 2004 Syracuse Baseball Wall of Fame press release, Fifield won 133 games for the Syracuse Stars, overall.

54 Per “News Notes,” Sporting Life, April 11, 1908: 16.

55 Fifield victories for Binghamton include a 7-3 win over Albany on May 15 and a 6-1 win over Amsterdam-Johnstown-Gloversville on May 25.

56 As reported in “State League Notes,” Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Times-Leader, June 17, 1908: 3.

57 Per “State League Notes,” Wilkes-Barre Times-Leader, June 29, 1908: 6.

58 “‘Happy Jack’ Fifield Now an Umpire,” Wilkes-Barre Times-Leader, July 14, 1908: 4.

59 “Sports,” Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Record, July 15, 1908: 12.

60 Per “John Fifield Dies at 68; Ace Pitcher in Big Leagues and for Syracuse Stars,” an unidentified obituary contained in the Fifield file at the GRC.

61 Same as above. Fifield’s Southern League umpiring stint is also noted on his TSN contract card.

62 “John Fifield Dies at 68,” above.

63 Same as above.

64 Mission statement posted online.

Full Name

John Proctor Fifield

Born

October 5, 1871 at Enfield, NH (USA)

Died

November 27, 1939 at Syracuse, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.