Jim Walkup

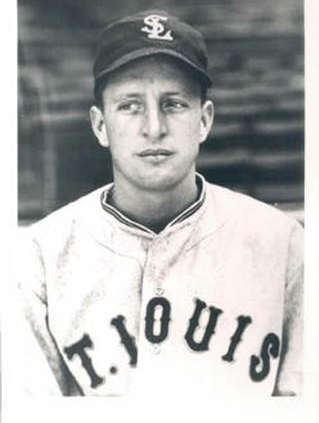

Jim Walkup, known by his middle name, Elton, for much of his playing career, was a hard-throwing right-hander with a devastating curveball. He debuted with the lowly St. Louis Browns in 1934 with comparisons to Dizzy Dean. Walkup, however, was plagued by control problems and never reached the potential many thought he possessed, posting a 16-38 record and unsightly 6.74 ERA in parts of five big-league seasons.

Jim Walkup, known by his middle name, Elton, for much of his playing career, was a hard-throwing right-hander with a devastating curveball. He debuted with the lowly St. Louis Browns in 1934 with comparisons to Dizzy Dean. Walkup, however, was plagued by control problems and never reached the potential many thought he possessed, posting a 16-38 record and unsightly 6.74 ERA in parts of five big-league seasons.

James Elton Walkup was born on December 14, 1909, in Havana, Arkansas. His parents were Huey Bart and Annie Jane (Dunlap) Walkup. Together they raised five children, who were born between approximately 1908 and 1921: Margaret, the eldest, followed by Jim, Florence, Burt, and Robert.1 The Walkups lived on a farm in Havana, a small town of about 600 residents located in the picturesque Petit Jean River Valley, flanked by the Ouachita and Ozark Mountains in northwest Arkansas.

Young Jim’s introduction to baseball was probably through his cousin, Jim, 14 years his senior, who also lived in Havana. Both were named after their paternal grandfather.2 Probably to avoid confusion, the younger Jim was called Elton. The elder Jim was a baseball prodigy and began his professional career as a 19-year-old with the Muskogee (Oklahoma) Mets in the Class D Western League in 1915. He had a cup of coffee with the Detroit Tigers in 1927, but earned his reputation as 5-foot-8, 150-pound “Little Jimmy,” whose impeccable control helped him to at least 233 wins in a minor-league career that lasted through the 1934 season.

After graduating from high school in 1928, Elton followed in his cousin Jim’s footsteps and enrolled at the University of Arkansas, located in Fayetteville, about 120 miles northwest of Havana. Sportswriter Jim Bohrat described Walkup as “doing some great pitching” as a sophomore in 1930.3 However, baseball was not a major sport at the school.

With the Great Depression tightening its grip on the American economy, Walkup left school after two years and returned to Havana, where farms were ravaged and prospects for employment limited. In 1932 he signed a professional baseball contract with the nearby Fort Smith (Arkansas) Twins of the Class C Western League. The lower minors were especially volatile during the financial crisis of the 1930s. In midseason the Twins relocated to Muskogee, whose team had moved and then disbanded. While pitching in Muskogee, Walkup was spotted by St. Louis Browns scout Ray Cahill, who was assessing Browns prospects in the league. Cahill was immediately impressed with the right-hander, who stood 6-feet-1, yet was thin at 170 pounds. “He’s got a curve like a big jug-handle,” gushed the scout.4 The Browns signed Walkup on Cahill’s recommendation. Walkup completed the season in Muskogee, going 9-14 for a 48-80 team and striking out 6.5 batters per nine innings, the second highest mark in the circuit.

Walker was assigned to the San Antonio Missions of the Class A Texas League in 1933. Less than two months into his tenure there, he was described as “sensational,” eventually posting a 15-11 slate with a league-most 146 strikeouts, while helping the Missions to the league championship.5 Despite Walkup’s wildness — 139 walks — league President J. Alvin Gardner raved, “I think he is one of the best young pitchers of the decade and I consider him a better prospect than Dizzy Dean was in his first year in the circuit.”6

Walkup was invited to the Browns’ spring training in West Palm Beach, Florida, in 1934. He was praised for his “great curve” and “real fast one,” but Cahill cautioned, “we may be bringing him up too soon. If the young man can get control, he’ll be good enough to stay.” He also added that Walkup will “give a catcher a busy day.”7 The Browns supposedly turned down an offer of $25,000 for the hurler, who was expected to vie for the last spot on the staff, which had posted the majors’ highest ERA (4.82) as a last-place team in 1933.

However, Walkup came down with arm troubles in mid-March. At the end of camp, he was optioned to the Milwaukee Brewers of the American Association. Skipper Allen Sothoron, a former Browns pitcher who once won 30 games in the Pacific Coast League, took Walkup under his wing. On a team featuring a quartet of hurlers who each logged at least 221 innings, Walkup served as spot starter and reliever, going 7-10 with a staff-best 3.85 ERA in 166 innings, while his 5.6 walks per nine innings ranked second highest in the league.

A September call-up to the Browns, Walkup debuted on September 22 at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis. He tossed two innings of mop-up duty against the Detroit Tigers, surrendering just one hit, but walking four and throwing a wild pitch which led to two runs. His other two outings, which consisted of no earned runs in 6⅓ innings and just one walk, pointed to a much brighter future.

During spring training in 1935, Browns manager Rogers Hornsby claimed his pitching staff was among the best in the AL, even with the offseason trade of Bump Hadley.8 Yet by mid-May, the team was without its two other most effective hurlers from the previous season, having also traded away Bobo Newsom and George Blaeholder. The result was a core group of seven hurlers, each of whom started between 17 and 24 games and relieved regularly. They became the first major-league staff to have three pitchers appear in at least 50 games in the same season, led by Walkup’s 55, which ranked second in the majors. (The other two were Russ Van Atta with 53 games and Ivy Andrews with 50.) Hornsby’s assertion, however, proved to be fallacious: Walkup had the ignominious achievement of posting the big-league’s highest ERA (6.25) while the Browns’ 5.26 team ERA was baseball’s worst.

Walkup’s season debut in 1935 was “superb” and “dominating,” gushed St. Louis sportswriter Glen L. Walker.9 He relieved starter Dick Coffman and held the visiting Chicago White Sox to one single over 6⅔ scoreless innings, earning the victory, 6-5, and the subheading “Walkup Saves the Day” in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat.”10 The excitement of that performance was tempered by his next four appearances, in which he was clubbed for 20 runs (18 earned) in just 8⅔ innings.

Highlights were few and far between for the Browns. The club drew a miserable attendance of 80,922 for the entire season, an all-time major-league low. The ongoing Depression was a factor, but the team was also uncompetitive, residing in the AL cellar most of the season before a late-season surge landed the Browns in seventh place (65-87).

One of those victories was Walkup’s “great exhibition,” according to sportswriter James M. Gould, an eight-hit shutout of the Boston Red Sox in the second game of a doubleheader at Sportsman’s Park on August 17.11 It proved to be the only shutout in Walkup’s career. In his most productive season in the majors, Walkup went 6-9 and logged a career-high 181⅓ innings. He yielded a major-league-most 11.2 hits per nine innings; while his 5.2 walks per nine innings were the second highest.

Walkup arrived at the Browns camp in 1936 with increased expectations. Hornsby predicted that the 26-year-old hurler would become “one of the pitching sensations of the circuit.”12 However, Walkup struggled during spring training, failing to win a game. Slated as a reliever to start the season, Walkup seemed to have gained Hornsby’s confidence once again after his “brilliant work,” wrote Gould, on April 26 against the Cleveland Indians.13 He tossed three-hit ball over 7⅔ innings of relief, but took the loss when two Browns errors contributed to an unearned run in the 16th inning. Given another chance as a starter, Walkup failed to reach the second inning in his two starts, yielding nine earned runs in 1⅔ innings. In mid-May he was optioned to the San Antonio Missions of the Texas League, where he finished at 10-11 with a sharp 3.19 ERA.

The 1936-1937 offseason marked a turning point in Browns history. The cash-strapped organization, which had been run by Phil Ball’s estate after his death in 1933, was sold to banker Don Barnes. As SABR members Greg Erion and Don Pajot wrote in their history of the Browns’ ownership, the AL had been pressuring the Ball estate to sell the club for several years because it had become a financial burden to teams visiting Sportsman’s Park, where Browns gate receipts did not cover their expenses.14 As noted, average attendance for the Browns had dropped to 1,079 per home game in 1935, marking the eighth of 18 consecutive seasons in which the team finished last at the box office.

The atmosphere at the Browns spring camp, which had moved to San Antonio in 1937, was not noticeably different despite new ownership promising changes. Hornsby, who still suited up for a handful of at-bats since taking over in mid-1933, was increasingly vocal in his displeasure with the team’s lack of talent and its long-held practice of selling its few productive players to meet basic day-to-day financial obligations.

Little was expected of Walkup, who (according to St. Louis sportswriter Ray Gillespie) “appeared to be headed back to the Missions” in 1937.15 Unexpectedly, Walkup got on a roll and emerged as the “sensation in camp,” remarked Gillespie.16 Coming off a major-league-worst 6.24 ERA, the Browns staff needed desperate help and hoped to ride Walkup’s hot hand.

Walkup’s name graced sports pages across the country after his season debut on April 24 in Cleveland. Described by Browns beat writer W.J. McGoogan as “an unheralded hope,” Walkup “pitched courageously,” tossing a complete game and overcoming eight hits and six walks to beat 18-year-old wunderkind Bob Feller and the Indians, 4-3.17 Gateway City scribes were in continual search for that rare nugget of good news for the Browns and this seemed like one. Wrote John Wray, sports editor of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch: “[Walkup] has tremendous speed, a good curve and a stylish delivery. Everyone who watches his work wonders why he is not in the upper bracket as a great pitcher.”18 He went on to answer his own rhetorical question: control, something that Walkup never mastered.

There was no fairy-tale transformation or ending for Walkup. In late June and early July, he tossed consecutive complete-game victories for the first and only time in his career, yielding just 10 combined hits. That improved his record to 5-5 (despite a 5.37 ERA). However, Walkup was unmercifully clobbered in his next four starts. Opponents bombed him for 40 runs (38 earned) and 58 hits in 31 innings. The Browns had few other options on the staff, which posted the majors’ highest team ERA (6.00) for the third straight season. Sunny Jim Bottomley, who had replaced the increasingly acrimonious Hornsby as skipper in midseason, was frowning by season’s end as the Brownies finished with 108 losses, the worst at that point in the club’s history. Walkup (9-12) led the majors in several dubious categories for hurlers with at least 150 innings, including highest ERA (7.36), most hits per nine innings (13.1), and highest WHIP (2.002).

The Browns got another new skipper in 1938: Gabby Street, who had guided the St. Louis Cardinals to the World Series title in 1931. Street proclaimed optimistically that he was “counting heavily” on Walkup.19 Given the Browns’ dearth of talent, the fiery manager known as Old Sarge had few other options.

Walkup had a frightful year in 1938, going 1-12, 6.80 in 18 games. In mid-July, he was involved in an “explosion on the bench” after Street pulled him from the game.20 Walkup supposedly referred to both the Browns and Street as “lousy” (and likely other choice expletives). He was subsequently fined and was suspended for one week.21 Upon his return on July 13, Walkup lost his 10th straight decision without a victory (and a 7.64 ERA). He was optioned to the Toledo Mud Hens in the American Association. Upon his return in mid-September, Walkup pitched an inning of relief and broke his losing streak. It took a small miracle: The Browns mounted a ninth-inning comeback to beat the eventual World Series champion New York Yankees in the second game of a twin bill.

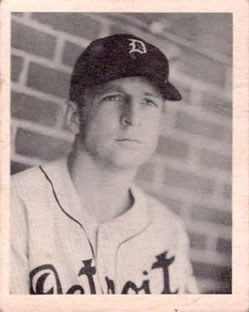

Despite Walkup’s dreadful performance in 1938, his knee-buckling curveball still drew raves from Browns brass. Vice President and GM Bill Dewitt predicted that Walkup’s breaking ball would “baffle all American League sluggers” in 1939.22 New skipper Fred Haney, the team’s fifth in the last three seasons, had coached Walkup with the Mud Hens and knew otherwise. Walkup made only one appearance, pitching two-thirds of an inning and picking up the loss on April 26. On May 13 he was shipped to the Detroit Tigers in a 10-player trade. Gateway City sportswriter Martin J. Haley described it as the “biggest major league baseball player deal consummated in many years.”23

Despite Walkup’s dreadful performance in 1938, his knee-buckling curveball still drew raves from Browns brass. Vice President and GM Bill Dewitt predicted that Walkup’s breaking ball would “baffle all American League sluggers” in 1939.22 New skipper Fred Haney, the team’s fifth in the last three seasons, had coached Walkup with the Mud Hens and knew otherwise. Walkup made only one appearance, pitching two-thirds of an inning and picking up the loss on April 26. On May 13 he was shipped to the Detroit Tigers in a 10-player trade. Gateway City sportswriter Martin J. Haley described it as the “biggest major league baseball player deal consummated in many years.”23

According to Detroit sportswriter Sam Greene, it was “generally understood that [Walkup] would not remain” with the Tigers.24 The righty made only seven brief relief appearances before the Tigers sold him outright to the American Association Toronto Maple Leafs in mid-July.25

Walkup spent the remainder of 1939 and all of 1940 with Toronto, as well as most of 1941 (when he had a short stint back with Milwaukee). After holding out in 1942, Walkup was released by Toronto.

Walkup enlisted in the US Army Air Forces in May 1942. While stationed at Chanute Field in central Illinois, he trained as an aviation technician.26 He eventually achieved the rank of sergeant and was qualified as “instrument specialist” assigned to the 399th Service Squadron at the Newport Army Air Field, located in northeast Arkansas.27 He played baseball for both base teams.

Discharged from the military in late 1945, the 36-year-old hurler resurrected his professional baseball career. After spending most of the 1946 season with the Henderson Oilers of the Class C East Texas League, Walkup enjoyed his best statistical season in 1947 with the Paris Red Peppers. He won 20 games and led the Class B Big State League with a 3.72 ERA. He logged more than 200 innings again in 1948, though his record fell to 8-18 in his last season of professional baseball.

In parts of six seasons in the majors, Walkup posted a 16-38 record and a 6.74 ERA in 462⅓ innings. He went 97-103 in 11 seasons in the minors.

Walkup’s lasting effect on baseball may have been the influence he had on another pitcher from Havana, Johnny Sain. Bursting on the scene in 1946, winning 20 games for the first of four times in five seasons for the Boston Braves, Sain revealed that he had learned his trademark curveball from Walkup. “Before Walkup reported in spring [in the 1930s], he and I would spend considerable time throwing to each other,” said Sain, eight years younger than Walkup. “He wised me up on a lot of tricks, coached me, tipped me, and gave me invaluable assistance. Walkup urged me to go into baseball.”28

After his baseball career, Walkup lived in Havana with his wife, Anna (McBride) Walkup. They met in Toronto, where her family had had settled after emigrating from Ireland when she was 12 years old.29 They married on January 6, 1942, and had two daughters, Sharon and Robin. Like his father, Walkup was a farmer.

Jim Walkup died at the age of 87 on February 17, 1997, at Chambers Memorial Hospital in nearby Danville, Arkansas. He was buried at the Havana Cemetery.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Len Levin and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com, SABR.org, The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record, the player’s Hall of Fame file, newspapers via Newspaper.com, and Ancestry.com.

Notes

1 Yell County Obits. https://yellcountyobits.org/obittext/obit352.html.

2 Newspapers typically referred to Elton as Jim’s nephew. However, according to the 1880 US Census, their fathers, Huey and William, were brothers with about a 16-year age difference.

3 Jim Bohrat, sportswriter at the Arkansas Democrat (Little Rock), was quoted in Flem R. Hall, “The Sport Tide,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 4, 1930: 15.

4 J. Roy Stockton, “Extra Innings,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 11, 1934: 19.

5 Associated Press, “Missions Divide Double Bill with Houston Buffs,” Longview (Texas) News-Journal, May 22, 1933: 6.

6 “$25,000 Hurler and Infielder to Join Browns,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 2, 1933: 8.

7 J. Roy Stockton, “Extra Innings.”

8 “Hornsby Compares Pitching Staff with Best,” The Sporting News, March 21, 1935: 5.

9 Glen L. Walker, “Browns Turn Back White Sox,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 23, 1935: 11.

10 Glen L. Walker, “Browns Turn Back White Sox.”

11 James M. Gould, “Browns Win Doubleheader from Boston, 11-7 and 7-0,” St Louis Post-Dispatch, August 18, 1935: 13.

12 Paul Michelson, Associated Press, “”Hornsby Aims At 5th Place for St. Louis,” Star-Gazette (Elmira, New York), March 24, 1936: 14.

13 James M. Gould, “Walkup Appears to Have Won Starting Job with Browns by His Brilliant Work Sunday,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 27, 1936: 15.

14 Greg Erion and Dennis Pajot, “St. Louis Browns Team Ownership History,” SABR.org, https://sabr.org/research/st-louis-browns-team-ownership-history.

15 Ray Gillespie, “Hornsby’s Spring Work Puts Him on Spot for Player Come-Back,” The Sporting News, April 1, 1937: 1.

16 Ray Gillespie, “Hildebrand an Ace in Rog’s Wild Deck,” The Sporting News, April 8, 1937: 3.

17 W.J. McGoogan,” Bob Feller Fans 11 in Six Frames, But Browns Win, 4-3,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 25, 1937: 19.

18 John Wray, “Wray’s Column,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 27, 1937: 14.

19 Associated Press, “Browns a Team Heavy on Hitters,” Moberly (Missouri) Monitor-Index and Democrat,” March 30, 1938: 6.

20 Dick Farrington, “National Split With American Over Radio, Declines to Let Landis Control Air Policies,” The Sporting News, July 14, 1938: 3.

21 Ray Gillespie, “Browns Suspend Pitcher Walkup for Verbal Row,” St. Louis Star and Times, July 7, 1938: 8.

22 Sid Keener, “Sid Keener’s Column,” St. Louis Star and Times, April 13, 1939: 26.

23 Martin J. Haley, “Newsom in 10-Player Trade Between Browns and Tigers,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, May 14, 1939: 1.

24 Sam Greene, “Jinx Takes Another Shot at the Tigers,” The Sporting News, July 27, 1939: 5.

25 United Press, “Pitcher Jim Walkup Is Sold to Toronto,” St. Louis Star and Times, July 22, 1939: 6.

26 “In the Service,” The Sporting News, September 17, 1942: 6.

27 “In the Service,” The Sporting News, April 29, 1943: 6.

28 J.G. Taylor Spink, “Looping the Loops,” The Sporting News, July 6, 1952: 6.

29 Yell County Obits. https://yellcountyobits.org/obittext/obit352.html.

Full Name

James Elton Walkup

Born

December 14, 1909 at Havana, AR (USA)

Died

February 7, 1997 at Danville, AR (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.