St. Louis Browns team ownership history

This article was written by Dennis Pajot - Greg Erion

This article was published in the Team Ownership History Project

Sportsman’s Park was home of the St. Louis Browns from 1902 to 1953. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.)

Introduction

Achieving on-field success has often proved elusive to owners of the Baltimore Orioles and its predecessor teams, the St. Louis Browns and Milwaukee Brewers. The franchise, dating back to the inception of the American League, frequently vexed its chief executives, including the likes of businessman Phil Ball, baseball impresario Bill Veeck, and more recently, attorney Peter Angelos. While the ballclub occasionally tasted victory, it endured long stretches of futility often aided by owner ineptness and undercapitalization.1

Competitive difficulties began in the team’s early years as the saying, “First in shoes, first in booze, and last in the American League,” became popular, capturing the Browns’ reputation for incompetence.2 When the team moved to Baltimore after the 1953 season, it had the worst franchise won-lost record of the eight ballclubs in the league. Even the Washington Senators, whose “First in war, first in peace, and last in the American League” epithet inspired the Brownie descriptive, had a better record than St. Louis.3 While Baltimore eventually began to field winning teams in the early 1960s they reverted to losing ways as the twentieth century ended, experiencing a run of 14 consecutive losing seasons.

Over the years, various owners contributed to subpar performances through unwise decisions. Ball made a fatal mistake in letting his general manager, Branch Rickey, go to the Cardinals. Rickey’s contributions to the Cardinals’ success eventually fueled the Browns leaving St. Louis. More recently, Angelos has received criticism for Baltimore’s dismal play during the past 20 seasons.

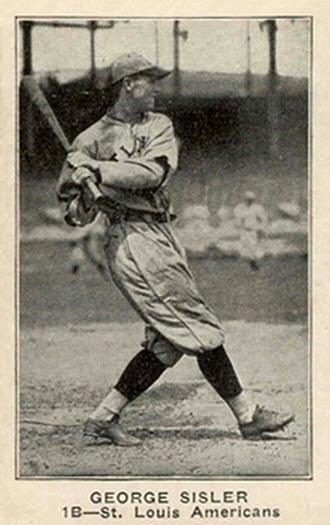

There were, however, periods of enlightened leadership. Robert Hedges, first owner of the Browns, promoted the game to a wider clientele by banning the sale of alcohol and instituting Ladies Day. His then-innovative reconstruction of Sportsman’s Park in 1908 into a steel and concrete facility led the way in designing future ballparks. Hedges also had the foresight to hire Rickey to run the team. While Rickey’s tenure was cut short by Ball, he was with the club long enough to obtain the services of George Sisler, the greatest of all Browns players.4

Brewery magnate Jerold Hoffberger presided over several decades of Orioles dominance as they won six division titles and two World Series. His organization served as a role model for all of baseball spanning the 1960s through the mid-1980s. In the 1980s, inspiration for the precedent-setting Oriole Park at Camden Yards was encouraged by Hoffberger’s successor, Edward Bennett Williams. Its retro style ushered in a new era of ballpark architecture, helping stimulate a renewed interest in baseball.

In the Beginning

Throughout the ballclub’s history, owners had to deal with daunting challenges such as scandals, strikes, and world wars. None, however, faced the experiences of brothers Henry and Mathew Killilea in 1901. They not only had to oversee the Milwaukee Brewers operations, but also assure the American League’s success in challenging the National League’s supremacy in baseball. Their ownership of the Brewers lasted only one year, a circumstance dominated by the overarching conflict between the two leagues.

After the 1900 season, Ban Johnson, president of the then Class A American League, announced that players under his jurisdiction wouldn’t be governed by the National Agreement, a covenant that decreed participants would honor a player’s contractual agreements with their respective teams. Effectively this meant he would begin raiding teams in the National League for their “reserved” players.5 Johnson was establishing a new major league.

He needed top-notch players for his league, and the National League’s self-imposed player salary cap of $2,400 per year made it easy to lure them to his fledgling organization. A rush of players to the new league was immediate. Eventually, nearly two-thirds of American League rosters came from the National League.6 Significantly, his raid included such standouts as Nap Lajoie and Cy Young.

In addition to attracting players through higher wages, Johnson played a longer strategy. A significant factor in determining a team’s financial viability was (and still is) the population base from which it drew: the larger the base, the greater chance of success. Placing teams in large metropolitan areas was paramount, especially before popular usage of the automobile left people were dependent on mass transportation. Shifting franchises to these locales became crucial for the league’s survival.

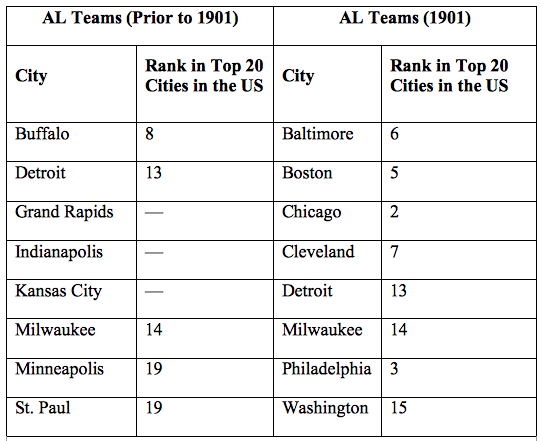

When the National League dropped Baltimore, Cleveland, and Washington after the 1899 season, Johnson added them to his circuit at the expense of less populated venues. Grand Rapids, with a population of less than 90,000, simply could not match Cleveland’s potential to draw fans from a base of over 380,000 inhabitants. Johnson also placed teams in Boston, Chicago, and Philadelphia to compete directly with the senior circuit. Detroit and Milwaukee, both founding franchises in the Western League, rounded out the new major league. As 1901 began, the rearrangement looked like this:

(Click image to enlarge.)

Source: 1900 US Census via InfoPlease.com

The league did well in 1901. Despite not having teams in two of the largest cities in the country, New York and St. Louis, Johnson’s clubs generated attendance of nearly 1.7 million, favorably comparing to the National League’s 1.9 million fans.

While these developments boded well for the American League, the same could not be said for the Brewers. Milwaukee’s performance in 1900 had been successful; it finished a close second to the Chicago White Stockings. But in 1901 the Brewers were overwhelmed by events stemming from the American/National League conflict.

With the movement of franchises to larger cities, Johnson also attracted substantial capital to Cleveland, Boston, Chicago, and Philadelphia. The Brew City’s Killilea brothers could not hope to compete financially with these owners, and their ability to successfully attract players from the senior circuit. It was a sad turn of events for Matthew Killilea, who had not only been active in running the Brewers but also proved a solid legal adviser to Johnson during the league war years.

Killilea, son of Irish immigrants, was an attorney and minor politician in Milwaukee. He and nine other local businessmen became involved with the Brewers as a matter of civic pride.7 Increasingly entwined in team affairs, he was instrumental in construction of Milwaukee Park at 16th and Lloyd, a facility designed to accommodate minor-league competition. Killilea developed a reputation for fairness in dealing with his players and extended efforts to provide a competitive team. Most often, however, until Connie Mack began managing the team, this last objective was not met, the Brewers usually finishing well out of the pennant race.8

Frequently called on to provide legal expertise as the league grew and conflict with the National League continued, Killilea was integral to the process of incorporating the White Stockings franchise for the 1900 season.9 Earlier, he had worked with Johnson to rebuff efforts to have Western League players transferred to the National League as well as securing new franchises to stabilize the growing circuit.10

Proprietorship of the Brewers went through several iterations over the years. By 1901 Henry Killilea as president and Fred Gross as treasurer were co-owners of the team.11 Killilea’s expertise notwithstanding, Milwaukee’s relative lack of financial backing became apparent when National Leaguers flocked to the new circuit. Beginning in the 1901 season, more than 100 players with experience in the senior circuit jumped to the Americans; more than 70 came directly in the first two years of its existence.12 Just three frontline players joined the Brewers; financial competition was just too keen for players to sign with Milwaukee.

Hugh Duffy, a future Hall of Famer, was the best of the three. Named manager to start the 1901 season, the 34-year-old, who had hit .440 in 1894, batted a creditable .302 in half a season. He replaced Connie Mack, who had moved on to the Philadelphia A’s, a shift orchestrated by Johnson to strengthen the new franchise. Other additions, pitchers Ned Garvin and Pink Hawley, generated a combined 15-34 record.

As if not drawing top-flight players was obstacle enough, Matt Killilea struggled with tuberculosis, which forced extended absences, further distracting the beleaguered franchise. Even before the season began, there were rumors that Milwaukee would move. Most suggested the team would move to St. Louis, if not in 1901, certainly in 1902.13

St. Louis was a logical destination, a metropolis Johnson had eyed for some time. It was the fourth largest city in the nation, with the added allure of preparing to host the 1904 World’s Fair. Unlike most East Coast cities, St. Louis allowed Sunday baseball, and competing for fans with the National League Cardinals made the contemplated move an even more attractive venture.14

The relocation rumors were true. Both Johnson and Chicago owner Charles Comiskey had requested that Killilea shift the team to St. Louis before the season began. Killilea refused “with protestations of civic pride,” at the same time promising that if the team did not perform well during the season he would move.15 That Killilea could resist Johnson and Comiskey was uncommon; most often the autocratic Johnson had his way. It reflected the regard both Johnson and Comiskey had for the Brewers owner.

While Killilea obtained a reprieve, he could not dislodge Johnson’s uneasiness as the season was about to start. After an exhibition game between Chicago and Milwaukee — handily won by Chicago — Johnson became alarmed at the Brewers’ level of play. He canceled further exhibition games between the two teams during the spring. “The games were unfair to the Milwaukee team and gave a false impression. The Brewers were not represented by their full strength and the opinion might be formed before the season begins that the White Stockings are stronger than Milwaukee.”16

Johnson’s concern was justified. Neither the franchise’s situation nor Killilea’s health improved. Killilea’s brother Henry, also an attorney, stepped in to direct the team during his brother’s absence, but to no avail.17 The team lost its first five games, bounced between seventh and eighth place for two months then settled into the cellar for good on June 30.

Earlier that month, a meeting of American League owners convened in Chicago. Afterword, news leaked out that St. Louis and/or New York would replace Milwaukee and/or Cleveland. Mathew Killilea countered the rumors, commenting that he would “personally vouch for the retention of this city (Milwaukee) in the circuit.” He said he had turned down an offer by St. Louis businessmen of $30,000 for the franchise.18

Despite these disavowals, talk of a shift carried through the season. Killilea continued to insist the Brewers would not move and were not for sale. In August, he said he had turned down another offer — now $42,000. By then, the impression had formed that Killilea was bargaining for the best price the franchise could draw. The team finished dead last, 35½ games behind the White Sox.

Attendance for the year at Milwaukee was 139,034, second to last in the American League, affected by continued rumors that the club was moving.

The season had not ended before The Sporting News reported that Jimmy McAleer, former manager of the Cleveland Blues and a great recruiter of National Leaguers to Johnson’s circuit, would manage the St. Louis team in 1902.19 This was before any word came that St. Louis would have a team.20 Over the next several weeks, additional stories found their way into TSN about the presumed move. The baseball weekly, operated by the Spink family in St. Louis, was particularly anxious to have an American League team in the city. Virtually every week through the next two months, an article referring to St. Louis replacing Milwaukee appeared in the paper.21

Matters came to a head in Chicago the first week of December when American League owners convened to discuss what seemed a foregone conclusion. While the franchise shift did take place, the path toward its doing so proved curious.

As Matt Killilea’s health worsened, his brother Henry had assumed a more prominent role in running the Brewers. Apparently, his part now included controlling ownership of the club. When American League executives sanctioned transfer to St. Louis with Matt still being associated with the club, Henry objected. Concerned with his brother’s well-being, he wanted Matt to retire from baseball. Matt wished to stay in the game. Finally, in a meeting that lasted nearly 12 hours, Henry gave up his interest and the transfer took place with Matt and treasurer Fred Gross controlling the new St. Louis franchise under terms that were not made public.22

Milwaukeeans were displeased. The Milwaukee Daily News denounced Killilea and Gross, saying they “have pink tea in their veins instead of sporting blood…” for not staying with Milwaukee. The Milwaukee Journal expressed similar sentiments, noting, “It is a very clever trick of the American League bunch in keeping Killilea … on their staff with ground awaiting them in Milwaukee in case St. Louis should go to the bead.”23

The Milwaukee Sentinel countered these reactions with a pragmatic observation: “The owners of the Milwaukee club removed their team to St. Louis as a business proposition. They expected to sell out, but in the absence of capitalists in the Mound City to shoulder the burden made it necessary for them to carry the load themselves, and it is possible they may make their independent fortunes as a result of the move. The Killileas and F.C. Gross stated that Milwaukee could not adequately support the expensive team they had secured; so they had to leave the city.”24

The Sentinel was perceptive. Killilea and Gross had maintained ownership of the team in the absence of local capitalists in St. Louis. The seriously ill Killilea and Gross, lifelong Milwaukeeans, did not make for a secure and stable St. Louis franchise ownership. It was an absence that did not continue for long; their control of the St. Louis franchise was short-lived. Ban Johnson was going to make sure of it.

Robert Hedges, first owner of the St. Louis Browns. (Library of Congress, Bain News Service)

Enter the Browns

“I went into baseball purely as a business.” — Robert Lee Hedges, Browns owner

Seeking to capitalize on past legacy, the new club appropriated the Browns as the team’s nickname. Even before the shift to St. Louis had been finalized it was being referred to as the Browns, a deliberate attempt to hearken back to the old St. Louis Brown Stockings, a successful franchise in the defunct American Association from the late 1880s that had won four pennants in a row.25

In late January 1902, it became public that Matt Killilea planned to dispose of his stock to St. Louis investors.26 Johnson on hearing of the impending deal “took the first train to St. Louis” and spent a day with the principal parties to ensure protection of league interests. While a St. Louis Republic article describing this development seemed to suggest rapidly evolving events, it actually represented culmination of a long process in attracting resident ownership of the team.

In this situation, Johnson was far from the detached individual portrayed by the Republic. Two days after Killilea’s intentions became public, it was revealed that Johnson and Comiskey “will meet with local parties who will take charge of the club” and that their names would soon be publicized. The Republic article surmised that one of the individuals involved in negotiations for the team was a Mr. R.L. Hedges, formerly of Cincinnati and then living in Kansas City.

Conjecture had it that Hedges, described as a retired carriage manufacturer, would have some connection with the ballclub.27 He and Johnson had known each other since Johnson was a sportswriter in Cincinnati; they had stayed in touch over the years.28

Although Hedges emerged as the major force in controlling the franchise, it was not apparent at first. When Sporting Life announced stockholders in the ballclub, they were with the exception of Hedges all prominent St. Louis businessmen. Ralph Orthwein, George Munson, C.J. McDiarmid, and John P. Bruce each committed to purchase 50 shares in the club valued at $100 per share, half paid up-front and representing 40 percent ownership.29 Hedges’ 300 shares were the remaining 60 percent, a majority interest in the Browns. Upon consummating the deal, Hedges moved to St. Louis. He lived there the rest of his life.

Numerous sources reflected various figures as to the team’s selling price; the January 28, 1902, issue of the St. Louis Republic estimating a figure in the range of $50,000. Whatever the final price, Henry Killilea seemed pleased with the transaction’s conclusion: “You may say that the deal has been hanging fire, but that everything was satisfactorily arranged. … Matt was never in favor of going to St. Louis, and when the opportunity came to sell out at a higher price he willingly consented. We were treated liberally by the men purchasing and have no complaint to make.”30

Matt Killilea died on July 27, 1902, a victim of tuberculosis. After his death, The Sporting News wrote of Killilea: “He was the brains of the American League, having advised Ban Johnson in all his moves before and after the war started with the National League. Even the genius, John T. Brush, with all his baseball experience, failed to cope successfully with the Milwaukee magnate, although the latter was new to the game compared to the Cincinnati man. Charlie Comiskey and other well known magnates have said that Matt Killilea had all the other leaders beaten by a mile when it came to base ball law.”31

Matt’s brother Henry went on to briefly own the Boston Red Sox (then called the Americans), possibly financed with some of the proceeds from the sale of the Browns. Respected for his legal acumen, Killilea received credit for his expertise in helping to gain peace between the American and National Leagues in 1903, the same year his Americans won the World Series.32

Once the transaction was final, the principals selected officers. Orthwein became president and Hedges secretary-treasurer. Several histories of the Browns have Orthwein heading the team in its first year. Although being president of the Browns reinforced this impression, Orthwein was a minority stockholder. Hedges was always the principal owner.33

Orthwein assumed the presidency to give the team a sense of legitimacy in the community. Hedges, from Kansas City, was viewed as an outsider. The Sporting News explained that Orthwein “was made nominal head of the new club to impress upon the public it was a St. Louis institution and not under alien ownership.”34 He was a millionaire, serving as secretary of the Sempire Clock Company and as director of the Orthwein Investment Company. Also known as a sportsman, Orthwein owned the then famous champion saddle horse Rex McDonald. At 25, he was the youngest president in either league.35 The paper noted that the club’s policies “would be shaped and affairs managed by Secretary Hedges who has a controlling interest in its stock.”

Orthwein proved a minor and transitory figure in the Browns history. He was a somewhat eccentric figure. In 1903 TSN noted creation of a deed of trust to manage Orthwein’s property and to “deal with his indebtedness,” one of several untoward incidents in his life.36 At the end of the 1903 season, a single sentence in the St. Louis-Dispatch noted that Hedges had succeeded Orthwein as president of the club.37 Although later versions of his leaving the Browns suggest dissatisfaction with the team’s management, Orthwein’s shaky financial position probably decided his departure.38

Hedges is an obscure figure in baseball’s narrative. His team lacked color, did not shine on the field or generate outstanding players. Yet, during his 13-year run as owner, Hedges showed an innovative side seldom equaled by his contemporaries.

While Orthwein came of wealth, his father generating a considerable fortune as a grain merchant, Hedges rose from more common stock. His tale of overcoming adversity ran along the line of a Horatio Alger rags-to-riches story. Born near Kansas City in 1869, he overcame several personal tragedies. His father died when Hedges was 13; four years later, two brothers were killed in a tornado.

Despite these calamities, Hedges worked his way up from being a civil servant to launching a buggy-manufacturing firm in Hamilton, Ohio. Always shrewd in the way of business, he sold the concern in 1900, foreseeing its’ future demise at the hands of a coming automobile industry. Hedges then moved into the financial world, representing J.P. Morgan’s various enterprises in the Midwest. Soon thereafter, lured by Johnson, he joined a select group of individuals investing in the American League.

Many owners at the time were former players or patrons who saw themselves as “sportsmen” indulging in a costly hobby or obligation to serve the civic good. Hedges was neither. “I went into baseball purely as a matter of business,” he said.39 Although the Browns’ performance was mostly mediocre during Hedges’ tenure, he held to this principle, with the Browns consistently turning a profit.

Taking over the Browns was a daunting proposition for Hedges. The first priority was finding a ballpark for the team. Old Sportsman’s Park, site of play for the American Association Browns, became the new Browns’ ballfield — partially out of availability but also hinting at past glories. Renovation of the disused facility commenced as a new grandstand was constructed and the bleachers restored amid a general makeover.40 It was ready for play on Opening Day 1902.

Through the winter months, while financial transactions took place, McAleer proceeded to sign players for the Browns, focusing on disgruntled National Leaguers. The results of his efforts were stunning; he obtained six players from the Cardinals alone. Three were pitchers Jack Harper, Jack Powell, and Willie Sudhoff, who had combined for 59 Cardinals wins in 1901. Future Hall of Famers Jessie Burkett and Bobby Wallace followed suit. With these and other players, the Browns looked to be formidable going into their inaugural season in St. Louis.

The wholesale invasion of the Cardinals’ roster set off a spate of lawsuits, the Cardinals defending their rights to control players through the reserve clause. Courts eventually upheld the Browns actions because then standard player contracts did not offer mutuality and were in violation of antitrust legislation.41

Of lasting importance was a legacy of ill feelings that formed between the two teams. Intracity rivalries were to be expected, but the Browns’ raid on the Cardinals generated a deep animosity that continued until the Browns left St. Louis. Hedges subsequently came to realize the cost to his team’s good will. He and said that if he had to do it over, he would probably have sought players from National League teams other than St. Louis.42

As the season commenced, Hedges found ways to improve attendance. One concerned the rowdy nature of fans attending Browns games. Ban Johnson’s continuing initiative in running the American League was to remove unsavory and disorderly elements from ballparks. His efforts encouraged increased attendance by a wider public, long put off by disruptive elements. Theodore P. Wagner, attending his first Browns game in the early 1900s, recalled half a century later, the gantlet of abuse fans had to endure: Women who attended “…received a raucous and often ribald welcome from the beer drinkers…” Wagner’s memories were of a “…Sunday afternoon filled with “brew bombs,” fisticuffs and excitement.”43

Although American League teams for the most part followed Johnson’s strictures on dealing with disruptive fans, the Browns were commencing play in a heretofore National League town where such limits had not been encouraged or endorsed. Hedges proceeded to promote a family-friendly environment by employing security personnel and banning the sale of alcohol at games. A complimentary initiative revolved around what became known as “Ladies Days,” games at Sportsman’s Park.

Hedges frequently receives credit for creating Ladies Day.44 In a series of articles nearly half a century after he took over the Browns, baseball writer Sid Keener said, “While many owners claim credit for introducing ‘Ladies Days’ to baseball this writer (Keener) awards that honor to Hedges. During the mid 1900’s women rarely patronized sporting events — baseball especially. There were those rowdies out on the ball field! And you didn’t want your mother, wife, daughter, or sweetheart to hear those nasty words!”45

Despite Keener’s recollections, the idea of encouraging women to attend ballgames took place in the National League’s early days and was an offered feature of Milwaukee Brewers baseball.46 Tickets were offered to women at a reduced price on special days of the week or if accompanied by a man. Although Hedges may not have come up with this promotional idea, he certainly popularized it in St Louis.

During the season, and over the years, Hedges became a familiar figure in St. Louis, attending business luncheons and civic functions, talking about his team, often providing free tickets with the invitation, “come out to the ball park as my guests.” To those wary of games based on prior experiences, “Uncle Bob,” as he came to be known, invited them to witness how attendance at a game had been transformed.”47 Hedges’ presence extended to the ballpark, where he often appeared, greeting fans, and roaming the stands during play, efforts that gradually won followers to the team.48

Keener recalled watching Hedges in action at the ballpark nearly a quarter-century later. “Two men and a woman who seemed to be in their early 60’s were trying to edge their way through the mob. There wasn’t a vacant seat in the ballpark when Mr. Hedges spotted them. ‘You’ll pardon me,’ said Mr. Hedges. ‘This place is too crowded for the lady. Won’t you be kind enough to do me a favor and accept seats in my private box?’ He had an usher escort them to his seats behind home plate to watch the game. He ended up viewing it while standing on a concrete post, holding on to an iron beam.”49

“First in shoes, first in booze, and last in the American League”

With new players recruited prior to the 1902 season, the Browns became a contender. Their first game was auspicious, a victory over the Cleveland Blues on April 24, 1902, at Sportsman’s Park. St. Louis went on to battle the Philadelphia A’s for the league lead well into September. At the height of the pennant race, Hedges’ innovative nature came into play: He offered his players 25 percent of the gross receipts should they win the league championship.50 Illegal today, it was a novel concept at the time. The gesture, however, proved academic as the Browns faded in the stretch, finishing second, five games out.

Fueled by their solid play, the Browns outdrew the Cardinals by over 45,000 fans, making for a successful season. Overshadowing the local scene, however, baseball’s landscape remained decidedly unsettled; the two leagues were still at war. During the winter of 1902, National League owners had come to the realization that the American League was here to stay. The new circuit had outdrawn the old, 2,206,454 to 1,683,012. It was time to end the conflict. Both leagues understood that profits would continue to decline as long as players could make one team bid against another for their services. The National League sent out peace feelers, which Johnson and his owners cordially received. Within weeks, a settlement to resolve differences concerning territorial rights and ownership of individual players came to the owners for approval.

While most were willing to sign off, New York Giants owner John T. Brush proved recalcitrant. Johnson, wishing to take advantage of New York’s population base, had shifted the Baltimore Orioles franchise into New York, begetting a team later to become known as the Yankees, a transfer that enraged Brush. Further, Brush was going to lose three quality stars, George Davis, Ed Delahanty, and Kid Elberfeld, to the American League. If these factors were not enough to set Brush against the settlement, he was also going to lose a star pitcher. Hedges had lured Christy Mathewson to the Browns with what looked to be a lawful “ironclad” contract. Mathewson had been making $1,500 annually with the Giants. Hedges offered $4,000. A $500 advance sweetened the bargain.51 Brush was so much against the agreement that he won an injunction to stop the process. Although he canceled the injunction, Brush remained opposed to the conflict’s resolution.

All indications pointed to Mathewson going to the Browns based on his having signed with them and receiving an advance. Yet the final listing of assignments had him staying with the Giants. By letting Mathewson stay with New York, Brush’s recalcitrance toward the settlement dissipated. It subsequently came to light that Hedges willingly gave Mathewson up to bring closure to the dispute. “My individual and club interests were of comparatively minor importance when the future of baseball was at stake,” he said. Later, he recalled, “I lost a pennant for St. Louis in that deal, but I brought about peace in the baseball world.”52

In retrospect, Hedges and St. Louis lost more than a pennant. One can only speculate on how Mathewson might have affected the Browns’ fortunes over the years, including the franchise’s eventual move to Baltimore.

The Browns’ success in 1902 proved their best performance during Hedges’ time as owner of the team. Just once more would they finish in the first division under Hedges; the rest of the time they resided in the bottom half of the league, including six finishes in seventh or eighth place. Although there were flashes of excellence, such as outfielder George Stone winning the batting title in 1906 and the acquisition of George Sisler, most of the talent Hedges garnered for the club proved second-rate. His astuteness in the business world did not translate into success on the playing field. Over the years, “Uncle Bob” gradually earned a new moniker, “Tail-End Bob.”

One reason suggested for the Browns’ plodding performances was that the ability to scout out top-notch prospects was lacking.53 Perhaps Hedges’ entry into the game from outside baseball worked against him. Unlike Comiskey or Mack, who had years of experience in developing a network of acquaintances able to discover talent, Hedges’ inexperience impeded his ability to ascertain quality personnel.

He also left an impression that in dealing with player personnel, his actions were as an individual dealing in commodities, rather than in creating a winning team. The Sporting News describes Hedges’ ability to obtain minor-league players who were “sold to major league clubs for large sums.” Yet, the same article noted, “Scarce one of these players ‘made good’ with the major-league clubs to which they were sold.”54 Hedges’ dealings in player personnel were so sharp they left fellow owners with a sense of unease, that he was “too canny a businessman for the good of the game.”55 This reputation eventually hurt him within baseball’s hierarchy, working against his ability to do business with other teams.

In time owners refused to trade with him. Sid Keener, writing for the St. Louis Times, wrote, “It has been common talk in American League baseball circles for years and years that other magnates would not exchange with Hedges. Figures prove this. … The American League, failing to shoo Uncle Bob out of the league, has entered into a combination to prevent him from getting his club back in the first division.”56 Cleveland and Philadelphia, respectively, thwarted his efforts to obtain Joe Jackson and Home Run Baker.

Despite the team’s less than sterling performances, it often turned a profit. Several external developments worked in Hedges’ favor. While Sunday baseball was legalized, horse racing became illegal in 1905. It had been one of few sporting events the public could afford. Simultaneously, Hedges continued innovating, introducing features to give the stadium a friendlier setting. He commenced use of an electric scoreboard, provided a public-address announcer at games, and employed detectives to rid Sportsman’s Park of gamblers.57 These factors contributed to increased attendance at the ballpark. Moreover, it did not hurt that the Cardinals were equally inept, finishing just once in the first division while Hedges ran the Browns. On average, the Browns outdrew the Cardinals by nearly 40,000 a year.

The Browns lumbered through several years of indifference until 1908. Then, thanks in part to picking up castoffs Bill Dinneen and Rube Waddell, they made a solid run at the pennant. Both had comeback seasons, keeping St. Louis in the race before they finished a close fourth. More than 600,000 fans came to the ballpark, over triple that of the crosstown Cardinals, and generating a profit of $165,000.

The Browns lumbered through several years of indifference until 1908. Then, thanks in part to picking up castoffs Bill Dinneen and Rube Waddell, they made a solid run at the pennant. Both had comeback seasons, keeping St. Louis in the race before they finished a close fourth. More than 600,000 fans came to the ballpark, over triple that of the crosstown Cardinals, and generating a profit of $165,000.

Flush with success, Hedges reinvested over $70,000 in reconstructing Sportsman’s Park, creating a steel and concrete structure, one of the earliest of its kind, and allowing for an increase in capacity from 18,000 to over 24,000.58 The refurbished facility provided little in the way of inspiration in 1909. Dinneen and Waddell dropped from a combined 33-21 to a 17-21 record as the team fell to seventh place. McAleer, too easygoing for his own good, some said, was let go after having piloted the team for eight seasons.59 Despite the increased capacity at Sportsman’s Park, the Brownies’ falloff caused attendance to drop from 618,947 to 366,274, sixth in the league.

To replace McAleer, Hedges hired Jack O’Connor, a former Browns catcher. Hedges had taken note of O’Connor’s “superior knowledge of the sport,” and “his knack of doing the unexpected or outguessing his adversary,” when O’Connor had played for the team.60 It proved a disastrous appointment. Not only did O’Connor lead the team to its worst record in the franchise’s young history, he involved the club in a disreputable incident, caught Hedges up in a legal battle, and decidedly raised the ire of Ban Johnson. All this came out of play on the last day of the season.

St. Louis was finishing last — 20½ games behind seventh-place Washington — as attendance dropped to less than 250,000. They were playing a doubleheader on the last day of the season against the Cleveland Naps. While the games had no meaning in the standings, they did play a role in the batting race. Cleveland’s Napoleon Lajoie, then second to the less popular Ty Cobb, made eight hits against Browns pitching, seemingly winning the batting crown.

His spree was achieved under bizarre circumstances. Most of Lajoie’s hits were bunts down the third-base line toward rookie Red Corriden, playing his position suspiciously deep. After a questionable play, Browns coach Harry Howell allegedly offered a bribe to the official scorer to give Lajoie a hit. Hedges, in attendance, was not pleased with what he saw.

As it turned out, Hedges wasn’t the only one displeased. Numerous complaints about the nature of the games surfaced. Johnson, getting a whiff of events, saw a threat to the integrity of the game and launched an investigation. Hedges soon fired O’Connor. It turned out that Corriden was playing deep under orders from O’Connor, who admitted, “The games Sunday were a farce.” O’Connor and Howell were banished from the game. When Hedges fired O’Connor and Howell, it was clear to those in the know that he was acting under Johnson’s direction.61

O’Connor was not finished with Hedges, however. His contract covered 1910 and 1911. Hedges refused to pay O’Connor for 1911. O’Connor took him to court and won in 1913, forcing payment of $5,000 for 1911.62 The case did little in the way of credit to either man, O’Connor being shown up for his lackadaisical management of the team and Hedges for his evasiveness on matters concerning the contract while under oath.63

Shortly after the season ended, rumors circulated that Hedges was going to sell the Browns. There was truth in the rumors; a transaction was in process. As recalled 40 years later by Hedges’ attorney, Montague Lyon, in The Sporting News, a group of St. Louisian Racquet Club members decided that they wanted to purchase the club from Hedges.64 Hedges at the time owned just over 60 percent of the club, minority stockholders being Ben C. Adkins, John E. Bruce, W.E. Orthwein and C.J. McDiarmid.65 The would-be purchasers, headed by local financier E. Manning Hodgman, deposited $30,000 with Hedges as down payment on a $300,000 purchase price. They had 10 days to determine whether to go through with the matter, failure to do so generating forfeiture of the down payment.

The reasons offered for Hedges’ decision to sell varied. Lyon was quoted in Sporting Life as saying, “Mr. Hedges’ health has been impaired by worry and hard work since the close of last season and his friends and his wife finally prevailed upon him to sell the club and accordingly the deal with the Hodgman syndicate was closed. After the stock has been transferred, Mr. Hedges will go to Arizona on personal business and finally to Europe for his health.”66

Other sources pointed to a different reason: that Hedges faced outside pressure, especially from Johnson, to sell the Browns. The article quoting Lyon alluded to efforts to oust Hedges because of the Browns’ poor showing, the O’Connor incident, and a disagreement with Comiskey concerning possible tampering charges involving a White Sox player. Comiskey, Hedges, and Johnson denied all this conjecture.

The deal, subsequently vetted by Johnson and others representing the American League, eventually collapsed. The would-be investors began squabbling about apportioning responsibilities in running the club, as a result missed payment deadlines for completing the purchase. Hedges granted an extension, hoping disagreements could be resolved, but the dispute went beyond resolution, and the transaction was never consummated. The investors lost their $30,000 down payment.

As the deal collapsed, Hedges, full of effusiveness, said he was “never feeling better in (my) life and is eager to get to work and resurrect the lowly Browns from the graveyard brigade.” Once the transaction failed, he rapidly reassumed control of the Browns and named shortstop Bobby Wallace manager for the 1911 season. It proved nearly as unfortunate a choice as was the selection of O’Connor.67

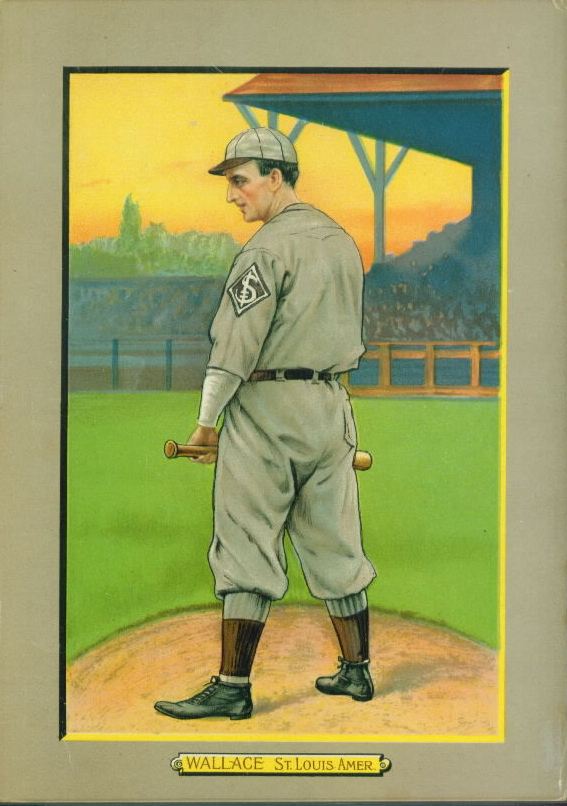

Wallace, the peerless-fielding shortstop, was a future Hall of Famer who had been with the Browns since 1902. He took the job against his better judgment. “I never had the slightest desire to be a major-league manager and all knew it,” said Wallace. “But Ban Johnson, Bob Hedges, and Jimmy McAleer persuaded me that the Browns were in a sort of a jam and it was up to me, as an old standby, to do what I could.”68

Wallace, the peerless-fielding shortstop, was a future Hall of Famer who had been with the Browns since 1902. He took the job against his better judgment. “I never had the slightest desire to be a major-league manager and all knew it,” said Wallace. “But Ban Johnson, Bob Hedges, and Jimmy McAleer persuaded me that the Browns were in a sort of a jam and it was up to me, as an old standby, to do what I could.”68

O’Connor’s efforts had generated a 47-107 record. With Wallace, the team’s record was near identical, at 45-107, prompting another last-place finish. Early in 1912, as the team continued to perform poorly, first baseman George Stovall replaced Wallace. The Sporting Life article describing his appointment as a playing manager provided insight into Stovall’s nature as well as his perspective on what St. Louis needed. “I am going to have a conference with President Hedges, and I am going to tell him that he will have to get me some players and get them in a hurry,” he said. “The club is in bad shape. … If he expects me to make a showing and win some games he’ll have to give me the material.”

The same article noted that the Browns were going through the motions, lifeless; that there were “no rowdies,” no “pepper and fighting spirit.” Mindful of Hedges’ business practices, the Sporting Life correspondent offered a telling observation: “[T]o make Stovall’s reign a success Colonel Hedges will have to bring along some of those high-priced minor-leaguers who go to other teams at fancy prices.”69

Under Stovall, the team marginally improved, enough to eke out a seventh-place finish ahead of the New York Highlanders (later Yankees). There was a sense of optimism as the Browns entered 1913 with Stovall at the helm. However, before the season was over, he earned Ban Johnson’s wrath for an on-field incident.

In early May, Stovall got into an argument with umpire Charlie Ferguson. As Browns infielder Jimmy Austin described it, the dispute climaxed when “George let fly with a big glob of tobacco juice — ptooey — that just splattered all over Ferguson’s face and coat and everywhere. Ugh, it was an awful mess. It was terrible”70 Suspended for several weeks, fined, and forced to write a letter of apology to Ferguson, Stovall complied. However, he had crossed the line with Johnson and Hedges, not only assaulting the authority of an umpire, but also behaving in a manner counter to the image of the game that they were trying to project. Stovall would have to go. Hedges, who had now made three consecutive poor selections as managers, did not have far to look in finding a successor.

Hedges Protégé: Branch Rickey

Branch Rickey came to St. Louis from the White Sox in 1905. A backup catcher, he was an oddity in the majors. Deeply religious, Rickey refused to play ball on Sundays and reported to the team only after he had completed coaching responsibilities at Allegheny College in the spring. He also proved to be a mediocre player.

Despite these drawbacks, Hedges was impressed with Rickey’s incisive knowledge of the game and an uncanny knack for evaluating talent. After Rickey’s playing career ended in 1907, Hedges and Rickey kept in touch while he continued coaching at Allegheny. Their association was one of mutual respect. Hedges admired Rickey’s baseball acumen. Rickey appreciated Hedges’ ability to advance in the world and run the Browns using solid business sense.71 Eventually Hedges hired Rickey, who was failing as a lawyer in Boise, Idaho, to do part-time scouting work for the Browns in1912. The next year he offered Rickey a position as assistant and business manager to start in June, after he completed his coaching obligations.72

Rickey’s joining the Browns came at an inauspicious time. Arriving on the heels of Stovall’s altercation with Ferguson and subsequent suspension, Rickey soon found himself in conflict with Stovall. Stovall sensed the precarious nature of his position. He chose to confront Hedges and by extension Rickey. Unhappy that Hedges would not grant him authority to make player transactions, he was dismissive of the talent Rickey wished to bring to the Browns, commenting, “I wasn’t running a primary school of baseball in connection with my work as manager of a big-league club.”73 This, plus a growing realization that Stovall was working to recruit players to the newly forming Federal League while still employed by the Browns, forced Hedges’ hand. He dismissed Stovall in September, replacing him with Rickey.74

Hedges’ decision to bring Rickey to St. Louis was sound, but events and situations limited the progress he could make. During Rickey’s time with the Browns, the team improved, but Hedges’ constrained financial situation and the emergence of the Federal League hampered progress. Although baseball history notes Rickey’s ultimately successful career, he was at the time a relative novice in the business of the game, experimenting with what worked and what didn’t. Although his ultimate loss to the Cardinals proved fatal to the Browns, there is no assurance that had he stayed with them he would have enjoyed the same success he later experienced with the Cardinals. The Browns were undercapitalized.

This was for the future. Rickey’s first order of business was to improve a club that had again finished last. Hedges felt the best way to do this was through development of a farm club or system. He had earlier explored purchasing the Kansas City Blues, asking Rickey to run the operation. Rickey, still tied to his coaching duties, turned Hedges down; the deal later fell through.75

The Browns, like all major-league teams, could protect only a limited number of players on their roster, placing excess talent on minor-league teams, rights to the player going to the minor-league club. Handshake agreements between major-league owners and their minor-league counterparts allowed return of the players should the player prove to be of big-league caliber. Frequently, however, this practice did not work. Players were often sold to the highest bidder; the work of scouts and teams who had found prospects went for naught. Such was the case with Hedges, as teams with more capital to draw on routinely outbid him.76

The need to establish a system to protect prospects grew more acute with the hiring of Rickey. He had a wide range of connections from his college-coaching days who referred players his way. Even before joining the Browns, Rickey had referred a player to Hedges, only to see him outbid.

In seeking to resolve this matter, Hedges and Rickey attempted another arrangement. An opportunity presented itself to fund local businessmen in Montgomery, Alabama, to purchase the Montgomery Rebels. Under the proposed arrangement, the Browns could acquire players off the roster for $1,000 at the end of the season. That deal fell through, as the prospective owners could not agree on financial terms. Subsequently, in January 1914, baseball’s then ruling National Commission ruled these types of agreements illegal.77 Although he was stymied, Hedges’ thoughts for working relations between major- and minor-league teams would see fruition under Rickey at another time and another place.

One player would not get away from the Browns. In 1912 George Sisler began to play for Rickey at the University of Michigan. Upon graduating, Sisler signed with the Browns, an act that eventually caused chaos in baseball’s hierarchy. Previously, when Sisler was still in high school, he had signed a contract with a minor-league club although he did not receive any money or play in any games. The contract eventually progressed through the minor leagues to the Pittsburgh Pirates, whose owner, Barney Dreyfuss, argued that Sisler belonged to him. After a protracted battle, which finally came to the National Commission for adjudication, it was ruled that the contract was invalid as Sisler was underage at the time of the signing. Having played for Rickey, who was by now with the Browns, Sisler signed with St. Louis. The commission’s decision proved so acrimonious that it was a contributing factor in the replacement of the commission by the commissioner system. Sisler went on to be the Browns’ greatest player. Once again, Hedges’ Browns had been in the middle of controversy.78

While these developments took place, spring training for the 1914 season had begun; Rickey applied his college-honed training techniques to major-league players. Sprinting exercises, sliding practices, various pitching drills, and lectures on baseball theory characterized St. Louis’s preparation for the 1914 campaign. These were radical concepts for which Rickey drew much ridicule. Cardinals manager Miller Huggins said, “I believe Manager Rickey has a lot of very good ideas, but I am not strong for theory.” On Rickey’s use of specifically designed sandpits to improve sliding skills, Huggins said, “No ballplayer can learn these things sliding in pits.”79 Despite such criticism, Rickey continued his training strategies.

It was a mark of Hedges’ management style that he not only backed Rickey’s unorthodox methods but also encouraged him to challenge the status quo. Hedges’ willingness to stand out from the crowd, to initiate a unique way of doing things, did not set well with his contemporaries. Rickey’s approach paid off as the Browns climbed out of the cellar into fifth place in 1914, winning 71 games, their best performance since 1908’s run for the pennant. Normally the Browns’ improvement would have been the source of great satisfaction. However, times were uncertain for established major-league baseball as the fledgling Federal League was competing for players and fans.

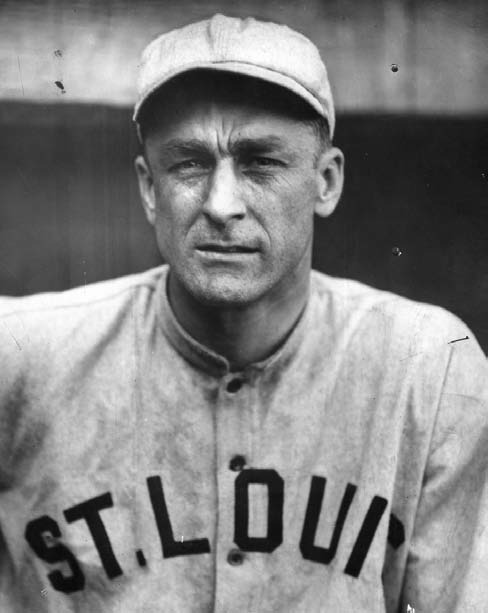

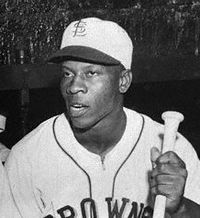

“Baseball people, as a rule, are generally allergic to new ideas.” — Branch Rickey, who struggled as the St. Louis Browns manager in 1913-15 before moving to the Cardinals and finding lasting success. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Unfortunately for the Browns, one of the better-financed Federal League teams was located in St. Louis. Underwritten by businessman Phil Ball, the St. Louis Terriers made serious inroads in the Mound City’s fan base. The Terriers’ emergence came just as Hedges seemed to be making headway in developing a contending team.

Prior to 1910, the Browns yearly attendance averaged well over 300,000. In their 1908 challenge for the pennant, it rose to more than 600,000. The team’s subsequent deterioration dropped attendance to near 200,000 each year from 1910 to 1913, the worst in the league and a drag on the American League’s overall financial viability. The team’s-fifth place finish in 1914 improved attendance, an accomplishment that might have been greater except for the Terriers’ presence.

However, in 1915, the Terriers became a contender, narrowly losing the championship to the Chicago Whales as both their St. Louis rivals finished sixth. Hedges’ club drew just 150,358 patrons, the lowest since he purchased the team.

As the 1915 season neared completion, plans developed to resolve conflict with the Federal League. Establishment of the league had hurt the two senior circuits as their gate dropped from over 6 million in 1913 to less than 5 million in 1914 and 1915.

The decreased attendance, coupled with escalating player salaries, strained most teams financially. At the same time, the Federal League’s failure to attract significant National and American League players, coupled with aggressive legal actions and indifferent attendance, contributed to a dubious future for the upstarts.80

Hedges had played his part in holding players within the American League. The Browns did not lose a single player off their roster to competing leagues. It was not for the lack of trying.

In 1914 Stovall, now associated with the Federal League, persuaded one of Hedges’ players, Earl Hamilton, to sign a three-year contract with the Kansas City Packers at twice what he was making with the Browns. Despite being in the midst of a three-year contract with St. Louis, Hamilton agreed. Upon hearing of the defection, Hedges met with Hamilton’s parents with an offer to renegotiate the contract. He convinced them that it was best not to sign with an “outlaw” league, and they persuaded Hamilton to stay with the Browns.81

All these factors led to demise of the Federal League. Fed players were dispersed to American and National League teams. What was not part of the agreement but understood by all parties to be a major factor in reaching settlement was that Phil Ball could purchase a major-league team, initially thought to be the Cardinals. This turn of events came out of meetings Ball and Johnson had beginning on the eve of the 1915 season. Years later, J.G. Taylor Spink related that in an attempt to hasten the end of the Federals, he arranged to have Ball and Johnson meet on a social basis at McTague’s, a local “gathering place for sportsmen.”82

It was an unlikely pairing of two iron-willed individuals but they found they enjoyed each other’s company. The two met on subsequent occasions and came to agree that the “ruinous war,” as Spink described it, needed to end. Johnson realized that if Ball were to become an owner in the majors, the transaction might aid in resolving the conflict. Likewise, Ball understood his rather substantial advantage in the situation.

Ball’s interest in the Cardinals failed to carry when their owner, Helene Britton, after showing initial interest in selling, decided to hold on.83 Johnson, who held considerable sway over American League owners, persuaded Hedges to sell. He likely had an easy time of it as Federal League competition had worn Hedges down. Toward the end of the 1915 season, after rain cancelled a lucrative doubleheader, he shared with sportswriter Sid Keener, “I don’t think I can take this much longer. This “war” with the Federals, a losing ballclub, and now a rained-out Sunday.”84 Tired, realizing that Rickey might be on the right track but that it would take too long to create a winning club, Hedges wanted out.

Hedges owned approximately 60 percent of the team as negotiations began. Ball received an option on the team provided he put down a $30,000 deposit before Christmas. As Christmas came near, Hedges seemed to be having second thoughts about selling.85 One of the Browns’ stockholders delegated to pick up the deposit showed up at Ball’s office right before Christmas, and said it was probably too late to go to the bank and get the $30,000. Ball asked if he wanted the deposit. “The banks are all closed, and you can’t get it now,” the stockholder said. Ball pulled out $30,000 in gold certificates. “Here it is.” The Browns representative refused to take it, sweeping it to the floor. Ball replied, “It’s okay. If you don’t take it, the woman who cleans up this place will.” Ball left the office. The Browns representative soon followed with the $30,000 in hand.86

The team sold for between $425,000 and $525,000. Various sources differ.87 Either way, Hedges realized quite a return on his $30,000 investment. The deal did not go smoothly. During final negotiations, it came out that there was a $40,000 liability because Hedges had been helping his ballplayers over the years with advances and loans. That issue was resolved but there was one final hangup. At the last meeting, there was a dispute over a tax of $4.90. Ball recalled, “I had already given drafts for over half a million dollars, and was not only hungry but disgusted. I finally tossed a $5 bill on the table and said, “Pay it, let’s eat.”

After leaving the Browns, Hedges stayed in St. Louis and went into banking. He died on April 23, 1932, the victim of lung cancer. In a bit of irony, his son Robert Jr. married the daughter of Sam Breadon, who eventually came to own the Cardinals.88

Robert Lee Hedges was the only Browns owner who made money on the team. He followed his stated goal of running the ballclub like a business, and in so doing ensured that games were fit for the public’s viewing. His innovations, providing announcers and electric scoreboards, and keeping rowdy elements out of the ballpark, helped popularize the game. Other ideas Hedges championed included the use of multiple umpires to officiate games and the establishment of a farm system to develop players. Both of these eventually came into being, the latter under his protégé, Branch Rickey. Shrewd in the business sense, generous, one who often saw a bigger picture than his contemporaries, Hedges twice took critical actions to end baseball warfare, in 1903 ceding Mathewson to the Giants and 1915 when he sold the Browns to Ball. Both steps brought peace to the game.

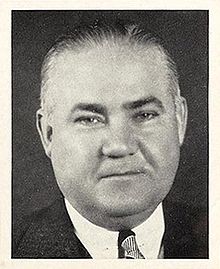

Philip De Catesby Ball

“For my own recreation”

Other than the fact that they were self-made men, Robert Hedges and Philip Ball were two distinct personalities. Hedges, while a perceptive businessman, was suave and smooth in his dealings. Ball showed an impetuous and short-tempered side while running the Browns. Their guiding light in running the Browns differed. Hedges saw it as a business endeavor, Ball a hobby to enjoy.

Under Hedges, the Browns were the more popular team in St. Louis. Although the Redbirds now have a rich history of pennants and World Series crowns, their performance during the first quarter of the twentieth century was dismal. During Ball’s first several years as owner of the Browns, they would continue to hold the advantage in attendance and popularity.

However, by the time Ball died in 1933, not only had his team lost favor to the Cardinals, more importantly the franchise had become moribund. He was one of many owners who presumed that because that they had thrived in other endeavors, success would follow in baseball.

Ball’s approach to running the Browns came out of an early drive to succeed and not a little bit of family heritage. Born in 1864, he came from Keokuk, Iowa. His father, Charles, was a captain during the Civil War and reputedly one of the most proficient poker players in the service. Ball’s great-uncle, Thomas Ap Catesby Jones, fought in the War of 1812 and the Mexican War.89 Jones partially inspired Ball’s mother, who named her son Philip De Catesby, dropping the Ap for De.90

Ball’s early years were adventuresome, embracing a wide range of experiences while roaming the country. He was a cowboy, worked on a railroad survey gang, and killed buffalo for their hides before getting into the ice industry.91 Ball’s interest in the business eventually led him to build refrigerated storage facilities. By the time his career ended, he directed a company that operated plants in over 150 locations throughout the United States, Canada, and Mexico, becoming a millionaire many times over in the process.

During his early years, while working at an ice plant in Shreveport, Louisiana, Ball played catcher for a local team and entertained hopes of a professional career. That hope ended during an altercation involving a knife, his left hand almost severed. His prospects dashed, Ball maintained interest in the game, manifesting itself as the Federal League emerged. Otto Stifel, a brewer prominent in Mound City politics and a booster of its interests, assembled a group of local businessmen, including Ball, to endow the effort. They raised several thousand dollars as an initial investment. Although well-intentioned, most of the participants did not command the massive financial wherewithal to fund a third major-league team for St. Louis.92

When the requirement came to fully vest in the club, virtually all of the original investors except Ball and Stifel withdrew. They backed the Terriers through the Federal League’s two seasons of existence, then purchased the Browns. Although Ball purchased the team from Hedges, he was not the sole owner, holding 2,850 (77 percent) of the 3,700 shares. Other owners included Stifel with 733 shares, James W. Garneau, 109 shares, and L.B. Von Weise and S.L. Swarts, 4 shares each.93 He later reminisced, “Baseball is my hobby. I got into the game with the Feds for my personal recreation, and I’m going to stick.”94

After Ball took ownership of the franchise, he wasted little time making changes. He named Fielder Jones manager, replacing Rickey. Jones had managed the White Sox to a World Series championship in 1906 and more recently nearly guided Ball’s Terriers to the Federal League pennant in 1915. The move was probably beneficial for the Browns, as Jones had proven success running a team while Rickey’s talents were best suited to front-office endeavors.95

The reorganized club had Ball as president with Garneau, Jones, and Stifle as vice presidents. Von Weise became the Browns secretary.96 Ominously for Rickey, he was not included on the slate of key officers. Ball’s opinion of Rickey was clear the first time they met. “So you’re the God-damned prohibitionist!” said Ball, swiping at Rickey’s teetotaler perspective on life.97 Despite Ball’s feelings, he was obligated to keep Rickey on the payroll thanks to a long-term contract signed under Hedges’ aegis.

The Browns prospered in 1916. Settlement of the Federal League conflict and Ball’s purchase of the team included transferring players from the Terriers to the Browns. The Browns gained pitchers Dave Davenport, Bob Groom, and Eddie Plank, whose combined 41-35 record helped generate a 79-75 record, their best since 1908. Attendance jumped to over 330,000, more than 100,000 better than the crosstown, last-place Cardinals.

Helene Britton may not have been ready to sell the Cardinals after the Federal League wars, but as the 1916 season concluded, she decided it was time to do so. She had just endured a painful divorce, the team was draining money from her estate, and, with attendance at a league low of 224,308, she wanted out.

A group outside St. Louis, collaborating with Cardinals manager Miller Huggins, showed an interest in purchasing the team. That option potentially included moving the franchise. Alarmed, local baseball-minded businessmen gathered and, working with Britton’s attorney, began to generate a plan to purchase the team through a public stock offering. As this process began, a search commenced to find someone to run the team. An informal polling of several sportswriters and sports editors unanimously suggested Rickey would be the best choice.98

Accordingly, the prospective purchasers through their spokesman, James Jones, approached Rickey about whether he had interest in becoming president of the Cardinals. Rickey, who had long understood his future with the Browns was limited, said he would speak to Ball about obtaining release from his contract. According to Rickey’s later recollection, Ball had assured him that if any opportunity came to improve his position, Ball would not stand in the way. And, Rickey said, Ball gave his permission, telling him, “I’ll help you with the contract. Have another meeting with those bastards and get enough to make it good.”

Armed with Ball’s encouragement, Rickey soon signed with the Cardinals; only to have Ball suddenly go back on his word. Ball’s about-face came after he heard from Ban Johnson. Ball told Rickey, “I’ve just talked to Ban Johnson. It’s all off. He said under no circumstances must this fellow be lost to the American League.” Rickey told Ball he had just signed a contract, there was no turning back. The Browns owner, fearing Johnson’s wrath, told Rickey he would deny ever having encouraged him to go with the Cardinals. Rickey, stunned by Ball’s about-face, responded, “Mr. Ball, whether or not I ever go with the Cardinals, I’ll never work another day for you!”99

Ball sought an injunction to prevent Rickey from breaching his contract. Ball winced as Rickey recounted their conversations in court, including his denigrating opinions of the prospective Cardinals owners. Faced with an increasingly uncomfortable position — Rickey would not work for him even if he won the case — Ball’s attorneys obtained an injunction delaying Rickey’s joining the Cardinals for 24 hours. Ball may have saved face on legal grounds but he lost overall. Because of this, more than any other factor, the Browns would eventually be lost to St. Louis. It was not apparent at the time or for a few years, but with Rickey’s move, the Cardinals franchise began to ascend at the Browns’ expense. It was telling that Johnson, not Ball, knew of Rickey’s potential.

One of the first things Rickey did after going over to the Cardinals was help put in place “The Knothole Gang.” This program, sponsored by Cardinals stockholders, allowed poor youngsters to attend games. Lifetime Cardinals fans came out of this promotional initiative, whose ramifications the Browns realized only too late.

Ball replaced Rickey with minor-league executive Bob Quinn. Quinn had been the longtime business manager for Columbus in the American Association. While he was not as broad a visionary as Rickey, Quinn’s reputation as a solid baseball executive and shrewd judge of talent attracted Ball.

Scrupulously honest, Quinn quickly set Ball straight on his business philosophy while negotiating to join the Browns organization. The Browns owner told Quinn, “There’s really nothing to the job. All you need is bunk and bluff.” Quinn replied, “I have never practiced bunk or bluff in my life.”100 That exchange reflected the different perspectives each had on running the ballclub. Moreover, it showed that Quinn knew how to deal with the aggressive and demanding Ball, who only respected those who stood up to him. Over the next several seasons, Quinn, interrupted by World War I and Ball’s occasional meddling, gradually assembled the great 1922 club that narrowly missed winning the pennant.

One never knew what Ball might do. Early in his ownership, Ball, who enjoyed flying, decided to fly into Detroit to see his team. Arriving at the team hotel, he went into the dining room to see his players. None were there. He learned that they took their $5 daily meal money, went to a cheap restaurant, spending about 75 cents, and pocketed the rest. Incensed, feeling he was being cheated, Ball dropped the per-diem arrangement, instead forcing players to sign for their meals in the hotel. Often generous, he balked at what he saw as being taken advantage of in matters as trivial as this.101

Quinn’s first year with the club, 1917, tested his resolve. The team fell to seventh, owing in part to several key injuries. As if this were not challenge enough, Ball’s meddlesome nature made a poor season miserable. The team had fallen into last place in September when Ball responded to the question “what was the matter with his team?” He responded that “he didn’t know, and wasn’t competent to judge, but that a lot of people had been telling him the players were ‘laying down’ on the manager and he meant to kid (sic) them where it would hurt — in their pay checks.”102

As a TSN article pointed out, it was one thing for “a thousand or two” other people to point out that the level of play was indifferent. It was quite another for the owner of the team to share such sentiments publicly. Ball subsequently claimed he had not said players were performing indifferently. However, by giving credence to the comments of others and saying that financial repercussions for apathetic effort might follow, he essentially endorsed those observations. Further exacerbating the situation, Ball made it known he thought only three players on the team, Jimmy Austin, Hank Severeid, and Sisler, were giving their all.

The next day Johnny Lavan, Del Pratt, and Burt Shotton, each of whom resented Ball’s comments, asked that he apologize. Ball backed off, and offered to have a retraction printed. Despite this, several days later Lavan and Pratt sued Ball for libel, setting off a chain reaction.103

Before the 1918 season began, St. Louis traded all three players — Lavan and Shotton to Washington, Pratt to the Yankees. The trial for libel began during spring training with plaintiffs commencing their efforts by deposing rival players to offer their opinions of Lavan and Pratt’s play. Ty Cobb averred during deposition that the pair “had always been honorable” and that Ball had “rushed into something without thinking.”104

Under the specter of additional players testifying throughout the season, pressure commenced to settle the case as soon as possible. Ban Johnson, Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert, and manager Clark Griffith of the Washington Senators pushed Lavan and Pratt toward resolution of the matter.105 Under pressure from their new teams, they agreed to settle the matter for $2,700 apiece.106 Significantly, Johnson worked the details out with Quinn, not Ball.

Although Ball claimed he did not have to pay a cent to settle the dispute, the American League footing the bill, he lost a fine player in Pratt. Part of the challenge St. Louis faced in the early ’20s was finding a serviceable second baseman. This incident reminded all that Quinn not only had to deal with the business of running a ball club, but managing an impetuous owner as well.

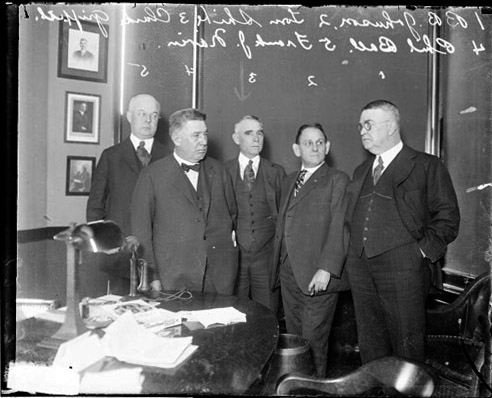

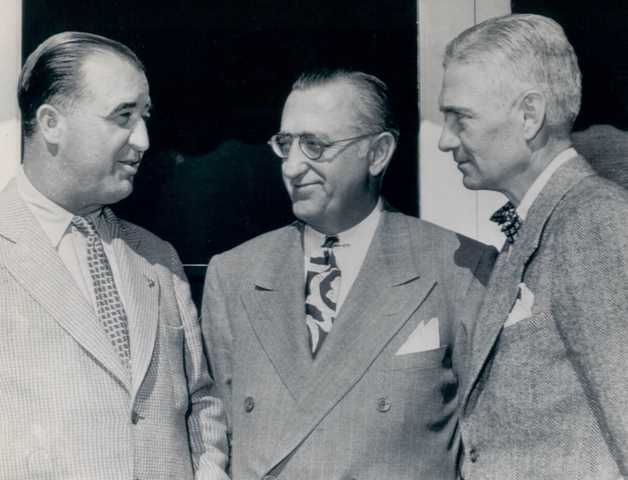

St. Louis Browns owner Phil Ball, second from left, meets with American League owners Frank Navin (Detroit Tigers, far left), Clark Griffith (Washington Senators, middle), Ben Shibe (Philadelphia A’s, second from right), and American League president Ban Johnson, far right, in Chicago, circa 1920. (Chicago History Museum, Chicago Daily News collection, SDN-062283)

The Browns, and all of baseball, felt the effects of World War I. At first the war had little impact on the game but as it continued, the draft, enlistments, or pressure to work in war-related defense jobs increasingly affected player availability. Additionally, in 1918, the government “advised” the major leagues to shorten the season by a month. Attendance at American League games in 1917 dropped 50 percent, from 3.4 million in 1916 to 1.7 million. Browns attendance decreased from 335,000 to 122,000. Amid these and other war-related incidents, Sisler biographer Rick Huhn wrote, attendance further suffered from race riots in the city, which helped deter fans from going to games at a segregated Sportsman’s Park. Ball and Quinn could do nothing more than bide their time on improving the franchise.107

Phil Ball is often recalled for his irascible tendencies, for speaking without thinking or interfering in the team’s operations, as he did in the case of Lavan and Pratt. Often overlooked is that Ball had the wherewithal to trust Quinn, giving him authority to make deals. It was Ball’s money to spend — he trusted Quinn to do it wisely. Once the war ended, Quinn resumed improving the team through trades and acquisitions. He obtained Wally Gerber, Bill Jacobson, and Ken Williams out of the military. Williams, second only to Sisler in ability, came to St. Louis as a pairing of Quinn’s ability to recognize talent and Ball’s willingness to spend $4,500 to obtain it.108 Quinn subsequently purchased second baseman Marty McManus from the minors as well for $5,000 a high figure at the time.109

Ray Gillespie, a sportswriter for the St. Louis Star, commented on Quinn’s role in running the Browns, “He and he alone could handle Phil Ball during his cranky spells.”110 On one occasion, he asked Ball to okay a $2,000 bonus for pitcher Urban Shocker. Shocker, obtained by Quinn from the Yankees in a deft deal, had won 20 games, one of four times he would do so for St. Louis. Ball sarcastically retorted, “What are you trying to do with my money — get generous?” He felt that players were not worthy of their salaries because they did not work as hard as those employed in his ice-plant business.111 Quinn was having none of that. “Not generous — only honest,” Quinn replied. Shocker received the bonus.112

Toward the end of his life, Ball claimed he made money on the Browns only once, in 1922, “not before or since” however, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch said that the 1924 season “marked the eighth time in eleven seasons the team earned money for the present ownership.” Presumably, that time span included Ball’s ownership of the Federal League Terriers.113

Ball’s outlook on how little he cared about making a profit made itself felt during Quinn’s tenure. As a story goes, Quinn called off a game with the Red Sox because of rain. An angry Ball asked, “What’s the reason for this? Why isn’t there a game?” Quinn told Ball there were only a few hundred fans in the stands and that the game would be part of a doubleheader, making the event more profitable. Ball roared at Quinn, “Bob Quinn, let me tell you something. I worked myself to a frazzle at the office so I could see this game, and if you want to keep your job, don’t ever do anything like this to me again.”114

While Quinn was building a contending team, Otto Stifel sold his minority interest in the Browns to Walter Fritsch.115 Stifel had induced Ball to become owner of the Terriers, then joined with him to purchase the Browns. For the most part, his was a silent presence. Prominent in local politics, he saw his finances begin to unravel over the years. Described as a “sportsman,” he lost heavily on horse racing. Stifel’s brewery interests fell victim to the imposition of Prohibition in 1918. Anticipating its impending passage, he converted his commercial activities to manufacturing of oleomargarine and butter substitutes, which proved far less lucrative. Less than a year after severing his connection with the Browns in December 1919, Stifel killed himself. He left a somewhat confused suicide note blaming his financial fall on Prohibition, banks, family, and friends. The note said, “I lost my head and appealed to Walter Fritsch and Phil Ball.” No further explanation of how they were involved in this tragedy ever surfaced.116

Fritsch, to whom Stifel referred, had purchased Stifel’s shares. A longtime acquaintance of Ball’s, Fritsch was associated with the Benjamin Moore paint company in St. Louis, specializing in promotion of their products for auto and rail manufacturers. More of a fan than anything else, he had little influence in running the club. Content with being treated as “one of the boys,” Fritsch often joined in spring-training drills, socialized with players and traveled with the club during the season.117 He maintained a box down the third-base line, often the first to buy his season ticket each year, even after selling his interest in the club.

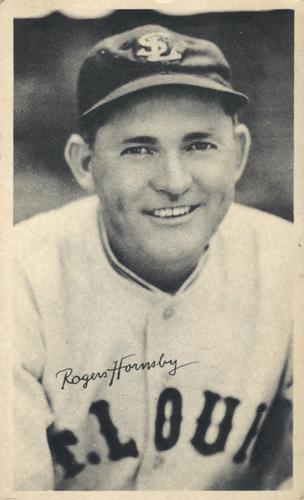

Under Quinn’s patient efforts, the Browns slowly improved, finishing fourth to reach the first division in 1920; they had not finished that high since 1908. They were still the favored team in St. Louis. The Cardinals under the management of Rickey on and off the field were steadily improving and drawing better, in no small part because of Rogers Hornsby, arguably the best player in the National League. The Browns countered with George Sisler, probably second only to Babe Ruth in the American League. More often than not, they continued to draw more fans than the Cardinals, in 1920 by over 90,000 fans.

In 1920 Ball made another decision that was a major factor in the eventual demise of the Browns franchise. Robison Field, the Cardinals’ ballpark, had fallen into a state of severe disrepair. Sam Breadon, by now the Cardinals’ president, did not have the wherewithal to refurbish or refinance a new ballpark. He estimated that it would cost over half a million dollars to overhaul the facility.118 By 1920, the place had become a firetrap, ready to collapse, Breadon was told by a building inspector friend that the ballpark would not pass a fire inspection.119

Desperate, not having the cash to fix the ballpark, Breadon approached Ball to see if he could rent Sportsman’s Park for the Cardinals’ home games. Ball rebuffed him: “Are you crazy, Sam? I wouldn’t let Branch Rickey put one foot inside my ballpark. Now get out yourself.” Facing financial calamity, Breadon was persistent. After several attempts, he finally asked Ball to listen to his plea. Ball relented.

“I was a poor boy — a very poor boy — in New York. I came here to St. Louis, nearly starved at first, but eventually made some money in the automobile business. I got into the Cardinals with that fan group — soon got in over my head — and much of my money is in the club. We’re heavily in debt, and our only chance to salvage what we put into it is to sell the Cardinals’ real estate (the ballpark) for $200,000, get out of debt, and move to Sportsman’s Park. You’re a rich man, Mr. Ball; money doesn’t mean anything to you, but I’m about to go broke, and only you can save me.”120

If anything over the years, Ball respected determination, and often behind his blustery façade resided the temperament of a caring individual. Breadon’s entreaty hit the mark.

“Sam, I didn’t know you were hooked so bad. I admire your frankness, and what’s more I admire a fighter, a man that doesn’t quit easily. Get your lawyer to draw up a contract, insert a rental figure you think is fair and I’ll sign it. Even if it included having that Rickey around the place.”121

With Ball’s agreement to take on the Cardinals as tenants, Breadon was able to sell Robison Field for $275,000, clear outstanding debts, and provide working capital for the future. One of the main initiatives Breadon — and Rickey — could now pursue was establishment of a minor-league system that generated competitive clubs for decades to come.122

The team improved in 1921, finishing third, and in 1922 came in second, one game behind the Yankees, setting an attendance record of almost 713,000. The Browns had reached the zenith of their popularity in St. Louis. Although various numbers were shared over the years, it was estimated that Ball made more than $300,000 in 1922.123 He was generous in sharing profits with players and management, an action that further contributed to undoing the franchise. A large bonus for Quinn enabled him to join a consortium of investors who bought the Boston Red Sox. Quinn was replaced by William Friel, a former player and minor-league executive. Friel never gained the level of confidence with Ball that Quinn had enjoyed. He lasted with the club until 1932 before being eased out of the organization.124

The team improved in 1921, finishing third, and in 1922 came in second, one game behind the Yankees, setting an attendance record of almost 713,000. The Browns had reached the zenith of their popularity in St. Louis. Although various numbers were shared over the years, it was estimated that Ball made more than $300,000 in 1922.123 He was generous in sharing profits with players and management, an action that further contributed to undoing the franchise. A large bonus for Quinn enabled him to join a consortium of investors who bought the Boston Red Sox. Quinn was replaced by William Friel, a former player and minor-league executive. Friel never gained the level of confidence with Ball that Quinn had enjoyed. He lasted with the club until 1932 before being eased out of the organization.124