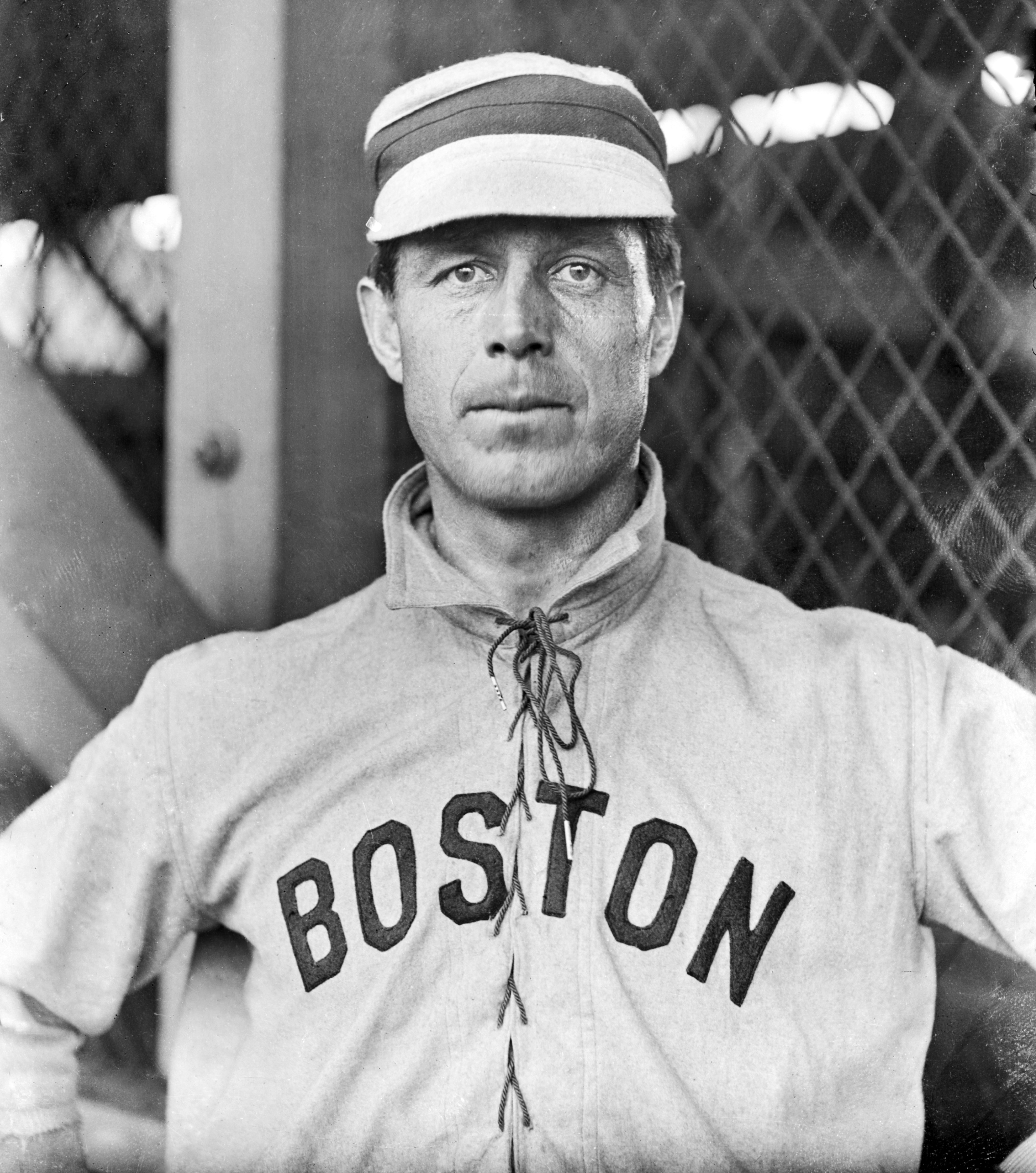

Jimmy Collins

The initial third baseman enshrined in the Baseball Hall of Fame, Jimmy Collins was an outstanding fielder and above-average hitter during his 14-year major-league career in the Deadball Era. As the first manager of the Boston franchise in the American League, Collins gained widespread acclaim when he led the team to consecutive pennants in 1903 and 1904 and victory in the inaugural 1903 World Series.

The initial third baseman enshrined in the Baseball Hall of Fame, Jimmy Collins was an outstanding fielder and above-average hitter during his 14-year major-league career in the Deadball Era. As the first manager of the Boston franchise in the American League, Collins gained widespread acclaim when he led the team to consecutive pennants in 1903 and 1904 and victory in the inaugural 1903 World Series.

Collins was a businessman in a baseball uniform. In an interview with the Buffalo Evening News just a few weeks before his death, he gave writer Cy Kritzer an encyclopedic recall of his salary levels as a ballplayer, practically gloating about once earning $18,000 in one year, but yet, as Kritzer related, “he couldn’t recall once during the interview the size of his batting average in any one season.”1 It wasn’t just about acquiring money, though. Collins used his baseball income to develop a real-estate business by building multifamily rental housing, which provided his income after his playing days.

James Joseph Collins was born on January 16, 1870, in the village of Suspension Bridge in Niagara Falls, New York, the second of four children of Irish immigrants Anthony and Alice Collins. The family moved in 1872 to Buffalo, where Anthony Collins worked as a policeman for three decades, rising to the rank of captain.

The Collins family first lived in Buffalo’s Irish-American neighborhoods in the southern section of the city. Irish-Americans were then the distinct minority in Buffalo, as they tussled for economic and political power with the dominant German-Americans on the East Side and the native-born Americans on the West Side. Collins’s father tutored him well in how to work effectively within the three ethnic groups that controlled life in Buffalo.

After receiving his early education in Catholic parochial schools, Collins attended St. Joseph’s College in downtown Buffalo. Despite the use of “college” in its name, St. Joseph’s was more like an advanced high school, more akin to a prep school today; its successor is a high school, St. Joseph’s Collegiate Institute. Collins graduated from St. Joseph’s in 1888 with a diploma in commercial studies, acquiring a business education that he put to good use in the coming years. After graduation Collins worked as a clerk in the Black Rock station of the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad, just a few blocks north of his parents’ new residence on Niagara Street in Buffalo’s native-born-American-dominated West Side.

The teenaged Collins honed his baseball skills by playing for amateur teams organized by the social clubs in Buffalo. In 1889 and 1890 he played outfield for the Socials, a team made up of Irish-Americans, which helped maintain ties to his old neighborhood. For the 1891 and 1892 seasons, though, Collins played third base for the North Buffalo team, based in the Black Rock section of the city, where he made the difficult decision to forsake his Irish-American ties with the Socials and forge new relationships with the men in his new neighborhood. Soon baseball changed his perspective on life and Collins abandoned his father’s traditional Irish-American value that deified job security.

When Jack Chapman, the manager of the Buffalo minor-league team in the Eastern League, offered Collins the chance to play professional baseball in May 1893, he left his secure job with the railroad for the uncertain life of a ballplayer and what he hoped would be greater income potential in the future. After starting out at third base, Collins played mostly shortstop for Buffalo during the 1893 season, finishing with a respectable .286 batting average, but an erratic .863 fielding average. When Chapman put Collins in the outfield for the 1894 season to minimize his fielding lapses, his batting average improved to .352 (among the league’s top 10 hitters) and he led the league with 198 hits.

In November 1894 the Boston ballclub in the National League paid $500 to obtain the services of the 5-foot-9, 178-pound Collins from the Buffalo ballclub as insurance should one of its outfielders stage a lengthy holdout in salary negotiations. Jimmy Bannon did hold out, so Boston manager Frank Selee put Collins in right field on Opening Day. After 11 games, though, the right-handed hitting Collins was clearly a less than adequate substitute for Bannon, as he was hitting barely .200 and had committed four errors. When Boston finally signed Bannon, Collins was expendable, so he was sold to the last-place Louisville team for $500 in a transaction characterized as a “loan” that was really a recall option.

Collins played in the outfield during his first few games with Louisville, before manager John McCloskey suddenly pressed him into service at third base midway through the May 31 game at Baltimore after the Louisville third baseman had committed four errors. The legend of Collins’s first major-league game at third base, like so many baseball legends, grew over time so that the more recent retellings – that he told Baltimore’s Hugh Jennings, “Bunt ’em down to me and I’ll show you something,” and then threw out four bunters in a row – bear only a partial resemblance to the 1895 facts.2 The bunters Collins threw out were fewer than four and occurred two months later (on July 28) after he became the regular third baseman in mid-June.

Since Collins flourished at third base in Louisville, Boston decided to exercise its recall option in August to have him temporarily fill in for an injured infielder. Collins, however, balked at returning to Boston. The brash Collins looked to leverage the situation and get a better deal from Boston, telling baseball writers that if he couldn’t stay with Louisville he’d retire from baseball and return to his railroad job in Buffalo. Boston relented and instead recalled Collins for the 1896 season.

After Boston traded its incumbent third baseman, Billy Nash, to Philadelphia in November 1895 to make room for Collins in the Boston infield, Collins showed tremendous chutzpah in his salary negotiation with Arthur Soden, the principal owner of the Boston ballclub. The strong-willed Collins thought the Nash trade gave him a negotiation advantage, so he held out for a higher salary until April 1896. Since the National League was a monopoly and the reserve clause in the player contract bound the player to a team until released, ownership had the upper hand in player negotiations. Collins learned a hard lesson that he had little leverage over ownership and finally agreed to a salary of $1,800 for the 1896 season. After performing well as the Boston third baseman in 1896, Collins was offered a salary increase to $2,100 for the 1897 season. Collins, however, felt he should be paid the unofficial salary maximum of $2,400. As he had been the year before, he was a holdout, but he eventually accepted Soden’s offer, which was four times the $500 average pay of an American worker.

Continual disagreements over money soured Collins’s relationship with the Boston ballclub and led to his highly publicized departure from the National League after the 1900 season. Collins had an easier time negotiating back home in Buffalo and in Louisville, where there was a more ethnically tolerant climate among the Irish-Americans, German-Americans, and native-born populations than the environment he found in Boston. There was a fundamental difference in ethnic relations in Boston, where the Irish didn’t just clash with the native-born Brahmin aristocracy over political, religious, and economic issues but indeed were the underbelly of society. In the 1890s the Brahmins (Soden included) controlled virtually everything in Boston, and considered Irish-Americans like Collins as simply pawns in their world.

In 1897 during Boston’s drive to the National League pennant, Collins matured into a graceful fielder and a consistent line-drive hitter who could find the outfield gaps. He became a fan favorite among the changing nature of the spectators at the South End Grounds, dubbed the Royal Rooters, who were middle-class businessmen that were displacing the gentlemanly crowd as ballpark spectators. In late September, more than 100 Rooters traveled to Baltimore to watch the Boston team play a crucial series there, where Collins, with a leech on his face to heal a swollen eye, led the team to victory in the series. Three days later Boston clinched the pennant.

While Collins finished the 1897 season with a .346 batting average, his real value was his ability to produce runs. Although the RBI statistic hadn’t yet been invented, a retrospective determination indicates that Collins would have had 132 RBIs in 1897, second among all National League batters. With the regular season over, Collins moved on to the supplemental income opportunities of the postseason. After the anticlimactic rematch with Baltimore in the Temple Cup series, Collins played for the All-America Baseball Team in a cross-country tour with the Baltimore team, where he observed Boston manager Frank Selee as businessman turn a profit on the itinerant baseball venture.

Collins quietly negotiated a contract with Soden to be paid the $2,400 salary maximum for the 1898 season. After three years as a National League ballplayer, the 28-year-old Collins had reached the pinnacle of his profession. However, because the National League owners lengthened the baseball season by 22 games to play 154 games in 1898, Collins felt duped by Soden, since Collins actually received just a minimal pay increase on a per-game basis.

Boston went on to capture a second consecutive National League pennant in 1898, as Collins compiled a .328 batting average, seventh highest in the league, and led the league with 15 home runs. Collins, who didn’t take kindly to having a boss, responded well to manager Selee’s approach to leave the ballplayers alone to play the game, a managerial style Collins adopted in the future. By now Collins had developed a stellar reputation as baseball’s best fielding third baseman, because he had a quick eye, good dexterity, extensive range, and a strong throwing arm. Collins covered a lot of territory at third base, not just bunts and groundballs but also snagging many pop flies in foul territory and in short left field.

At a team testimonial in October 1898, Selee received a $2,500 check from Soden to share with the players, as a “gratuity” for winning the pennant. It must have galled Collins to receive a “tip” as if he were a Pullman Car porter. It was one more signal to Collins that his income potential was very limited by working for the Boston ballclub. Indeed, he had no success in securing a salary increase for the 1899 and 1900 seasons.

During the winter of 1900 Collins made an investment to take advantage of the explosive future growth he saw in the nascent South Buffalo neighborhood, to which Irish-Americans had begun moving from the inner city. Collins purchased a house lot and made plans to construct a rental unit on it. This was the first of many properties Collins purchased as he planned to live off the rental income as a self-employed person during his post-baseball years.

Collins doubtless saw no benefits in a future with the Boston National League ballclub. Given the penurious ways of the Boston owners, he was likely to face a decrease in salary as age took its inevitable toll on his playing skills. He had no chance to succeed Selee as manager and had been passed over as captain. One ray of hope for Collins to get an increased salary was the formation of the Players Protective Association in 1900. Collins was one of Boston’s player representatives in the fledgling players union, but he was also looking out for his own interests. After attending two union meetings that summer and seeing no action on the compensation front, Collins took matters into his own hands.

In March 1901 Collins became the manager, captain, and third baseman of the Boston team in the new American League, which Ban Johnson had established as a second major league to compete against the monopolistic National League. Collins justified jumping leagues at the time by saying, “I have given the National league people my best efforts for several years past and often asked them for more money, knowing that I was worth it, but until now they have turned a deaf ear to all my requests. …I saw a chance to better myself and took it.”3

Since Collins was motivated by money and displeased with his history of salary negotiations with the Boston Nationals, he was willing to take the risk of switching over to the Boston Americans. The possible failure of the new baseball enterprise and of being blackballed by the National League were not big risks to the 31-year-old Collins; he could simply fall back on his real-estate venture and connections in Buffalo. Collins was not only pleased that he could be a manager in the American League, but he was also intrigued that former ballplayers could also be part-owners, as exemplified by Connie Mack in Philadelphia.

Collins was handsomely compensated for jumping leagues. His contract with the Boston Americans called for a $3,500 annual salary for three years, nearly a 50 percent increase over his $2,400 salary for the 1900 season, with no reserve clause to restrict his freedom to negotiate with other teams thereafter. This $10,500 package was a key aspect of the deal for Collins, so that he’d have additional capital to invest in his real-estate business. Charles Somers, the owner of the Boston club, agreed to add a personal guarantee concerning the salary payments, to negate Collins’s risk if Soden took legal action to try to enforce the reserve clause that he thought legally bound Collins to the National League ballclub. Collins was also a nominal owner of the Boston Americans, being awarded a few shares of stock in the club.

The timing of Collins’s switch to the American League was impeccable from a cultural perspective, coinciding with the rise of Irish-American political power in Boston. John Fitzgerald, a member of the Royal Rooters, was a congressman in Washington (and soon would be mayor of Boston), while Patrick Collins became the second Irish-American mayor of Boston. From 1902 to 1905, two men named Collins were the toast of Boston among the city’s Irish-American citizens: the mayor and the baseball manager.

Collins piloted Boston to a second-place finish in 1901 and to third place in 1902, while producing .332 and .322 batting averages, respectively, as the team’s third baseman. Because the Royal Rooters followed Collins and transferred their loyalty, the Americans outdrew their rival Nationals at the ballpark, becoming the more popular team in Boston. Collins seized the opportunity to renegotiate his contract each year, nearly doubling his 1901 salary by the beginning of the 1903 season.

Collins was successful as a baseball manager because he extended to the baseball diamond his general contracting skills from his house-building activities in Buffalo, where he had to depend on highly skilled, motivated workers to build well-constructed houses for him. In this fashion, Collins adopted the same philosophy that his former manager, Frank Selee, had used during his five years with the Boston Nationals: find good ballplayers and let them do their jobs without interference. Because he was able to motivate his players through his on-the-field activities as a third baseman, Collins was more of a leader “among” men than a leader “of” men. It was the “we’re all in this together” attitude that enabled Collins to win two American League pennants as player-manager and lead his team to victory in the first modern-day World Series.

Offsetting these positive attributes as manager, Collins had several flaws, primarily that he stayed too long with veteran players and failed to adequately mix in younger players to prepare the team for the future. His problem with handling aging ballplayers was compounded by his weakness in talent evaluation, which stemmed in large part from his inability to build an effective network of contacts to acquire new talent in that pre-farm-system era.

While he continued to perform as a third baseman in Boston for five more seasons, Collins focused more on the leadership functions of his job and his activities to improve the stature of the American League and its president, Ban Johnson. Two developments in 1903 elevated Johnson’s gratitude to Collins for making the new league a success: the peace conference between the two leagues in January 1903 and the first modern-day World Series in October 1903. Both developments solidified Johnson’s stature as an influential baseball executive, and they enabled Collins to enjoy several more years of financial prosperity as well as indulgence by Johnson as his reward for jumping leagues in 1901.

When the Boston Americans secured the American League pennant in September 1903, new Boston owner Henry Killileaand Pittsburgh owner Barney Dreyfuss agreed to play an interleague postseason series in October. The agreement provided for the owners to share revenue from the games, but did not include a provision to pay the ballplayers. Since the contracts of the Boston players expired at the end of September, Killilea had foolishly entered into a contract to play a postseason series without securing the services of the Boston ballplayers. Collins exploited Killilea’s poor business judgment to negotiate a great deal for the ballplayers. They got not just 75 percent of Boston’s portion of the shared revenue under the World Series agreement, but 75 percent of all of Boston’s net revenue from the series.4

After Boston lost three of the first four games of the best-of-nine-games postseason series, Collins led the team, accentuated by the Royal Rooters’ incessant singing of the song “Tessie,” in a comeback to win the next four games to become the World Series champion. In the eyes of the sporting public, the victory over the National League established the legitimacy of the American League. At the time Collins believed these postseason games to be merely meaningless exhibitions to generate additional income, based on his experience in 1897 with the Temple Cup series and the All-America tour. However, he took advantage of the national belief that the 1903 World Series determined baseball supremacy. Indeed, the vast majority of his wealth garnered from major-league baseball between 1904 and 1908 was the direct result of his national acclaim from Boston’s 1903 World Series victory.

After the World Series victory, Collins negotiated a new three-year guaranteed contract with Killilea, who was seeking to retain his services so he could sell the ballclub, which paid Collins a $10,000 annual salary and had a profit-sharing arrangement equal to 10 percent of the club’s profits over $25,000.5 In April 1904 John I. Taylor, the son of Boston Globe publisher Charles Taylor, became the new owner of the Americans. Collins’s clash with the inexperienced Taylor led to a testy feud that eventually led to Collins’s departure from the Boston Americans three years later.

Collins led an aging Boston team to a second consecutive pennant in 1904, in a neck-and-neck battle with the New York Highlanders in the first installment of the longstanding rivalry between the Boston Red Sox and New York Yankees. Unlike 1903, when Boston participated in the first modern-day World Series, the 1904 championship had no similar culminating event, as the National League champion New York Giants refused to play such a series. Although Taylor honored the profit-sharing provision in Collins’s contract, the $8,000 payment on top of Collins’ $10,000 salary stuck in the owner’s craw.

An article in the Boston Globe Magazine in January 1905 portrayed Collins as an up-and-coming businessman. Accompanying the article was a portrait of Collins dressed in a suit, white shirt with raised collar, cravat loosely knotted at the neck, with a watch fob draped across his breast. He looked like any well-to-do Boston Brahmin, not a baseball player. Three photos of his rental properties in Buffalo were also included. “For several winters he devoted his time to looking after the new buildings he was erecting,” writer Tim Murnane wrote of Collins’s dedication to this business venture, “and even now with several fine pieces of real estate, he has planned for two more new houses.”6 Collins was now more businessman than ballplayer, which accelerated Taylor’s dislike for him.

Collins also displayed more hubris during the 1905 baseball season, indicating that he believed the Boston Americans were his team, not Taylor’s. Collins had run the baseball operation for three years without any direct oversight by the ballclub’s absentee out-of-town owners before Taylor became the owner, and had successfully engineered a second straight pennant-winning season in 1904 without Taylor’s assistance. This was the dark side to the soft-spoken but ambitious Collins.

Taylor took a more active role in the team for the 1905 season, seeking to remedy the team’s injury and age issues, not by providing the resources to Collins so that he could fix the situation, but rather by fancying himself as a recruiter of baseball talent to rescue the team on his own. Not only did Taylor’s signings do nothing to improve Boston’s chances for victory on the baseball field (the team finished in fourth place), they intensified Collins’s smoldering animosity for Taylor. While hidden from the public during the baseball season, the feud spilled onto the sports pages in December.

In a late December meeting in Buffalo with Ban Johnson, Collins leveraged his favorable relationship with the American League president to push him to honor the verbal commitment made back in 1901 for Collins to eventually obtain an ownership interest in an American League ballclub. Johnson then exiled Taylor to Europe for a six-month vacation. The timing was perfect to take advantage of John Fitzgerald’s becoming mayor of Boston in January 1906 as the city’s first American-born Irish Catholic mayor, to increase the influence of the Royal Rooters among Irish-Americans and take advantage of transportation improvements (train connections and automobiles) that would bring suburban spectators to the Americans’ Huntington Avenue Grounds.

Although Johnson temporarily assumed the role of Boston owner, Collins was the acting president of the Boston ballclub. To reflect his new duties, Collins extended his guaranteed contract for two more years, through the 1908 season. At the same time, he made his first investment in a baseball organization when he became a one-third owner of the minor-league Worcester, Massachusetts, club in the New England League.

With Taylor out of the way for the 1906 season, Johnson gave Collins a tryout as president. However, just when he was on the cusp on moving from the baseball diamond to the executive suite, three factors combined to derail Collins from achieving his ultimate goal in professional baseball. First, Collins discovered that he just wasn’t good at the job of being an executive, which changed his relationship with the ballplayers. Second, the early success of his investment in the Worcester ballclub nudged him to modify his goal to be a minor-league owner rather than one at the major-league level. Third, Collins, a 36-year-old bachelor, looked to marry his longtime girlfriend.

Over a two-year span following consecutive American League pennants, Collins plummeted from revered hero to reviled bum. A 20-game losing streak in May 1906 sank the team into last place, where it stayed for the remainder of the season. On July 1 Collins abruptly left the team and made his fateful decision to stop performing all his duties for the Boston ballclub to focus on his personal future. He made just two brief returns to the team during the summer. On August 29 the front-page headline in the Boston Globe told the whole story: “Capt. Jimmy Collins No Longer at Helm: Indefinitely Suspended by Boston American League Club.” After Collins’ several absences without leave, Johnson used the term “desertion” in the press announcement.

Collins’s decision to desert the Boston Americans was a disaster. He struck out at buying into ownership in the Buffalo and Providence ballclubs of the Eastern League, believing the asking prices to be too inflated to justify the investment. By December Collins was negotiating to return to Boston as its third baseman for the 1907 season, since he had a guaranteed contract to play through 1908 with the Boston Americans. Because Taylor, now back from his extended European vacation, was legally obligated to pay Collins whether or not he played, he agreed to take Collins back as a player, but not as manager.

During the winter of 1907 Collins secretly married Sarah E. “Sadie” Murphy before he left for spring training. The news of the marriage wasn’t reported in the Boston newspapers until after he was traded on June 7 to the Philadelphia Athletics, when old friend Connie Mack agreed to take on Collins and his contract to bolster the A’s infield to make a run at the pennant. By August Philadelphia had climbed from fourth place to first place, but then lost the pennant after a late September swoon. In August 1908 Mack excused Collins from the team’s season-ending road trip so he could try out some minor-leaguers at third base to replace Collins in 1909, which gave Collins some time to contemplate his next step in baseball and enjoy some family time with his newborn daughter, Agnes.

For the 1909 season, Collins had to settle for being player-manager of the Minneapolis Millers in the American Association. Early in the season, however, Collins suffered an off-the-field tragedy when 8-month-old Agnes died in Buffalo. Collins returned to Buffalo to console his distraught wife, who was now four months pregnant, and made arrangements for Sadie to return to Boston so that she could be with her family for the next five months of her pregnancy. In early July Minneapolis moved into first place, but faded down the stretch to a third-place finish. Just before the season ended, Collins received word from Boston that his daughter Kathlyn had been born.

Now living with his family in Boston, not Buffalo, Collins sought a position near Boston. In October 1909 he was hired as the manager of the Providence team in the Eastern League, which was owned by Charlie Lavis, a former Royal Rooter. He lasted only a season and a half at Providence, being fired in June 1911; his passive managerial style didn’t produce results in an era dominated by intimidating managers. Collins’s hope to become the majority owner of a minor-league ballclub was dashed, as prices continued to skyrocket at what turned out to be a height of popularity of minor-league baseball. In January 1912 his daughter Claire was born and Collins sold his one-third interest in the Worcester ballclub and left Organized Baseball.

Settling into Boston was challenging for Collins. During his days as a popular player-manager, he had managed to navigate the ethnic stratification between Boston’s Brahmin society and its Irish-American underclass. Now, as just another former ballplayer, he couldn’t establish himself in business in the city. Collins was even rebuffed when he tried to become the baseball coach at an Irish-American institution, Boston College. In 1914 the family moved back to Buffalo, where Collins purchased a house in South Buffalo near his rental properties and settled into a quiet life as a real-estate mogul.

In 1922 Collins was appointed president of the Buffalo Municipal Baseball Association, in the wake of a corruption scandal in the Buffalo Parks Department, which sent to prison the former head of the city’s amateur baseball leagues. Collins served 22 consecutive terms as president of the muni-league, during which he helped to expand the opportunity for thousands of youngsters to develop their baseball talents in the city-run amateur leagues, a vast improvement over the former system of social-club leagues in which Collins had played that could accommodate only a few hundred players.

As muni-league president, Collins’s reputation as a great major-league ballplayer spread among a new generation of baseball fans and sportswriters in western New York. John Meahl, the commissioner of the Buffalo Parks Department, was not bashful about profusely praising Collins as baseball’s “greatest third baseman of all time.”7 As a result of Meahl’s promotional efforts, Collins’s baseball reputation soon spread beyond regional newspapers into national publications. During the 1920s his name regularly surfaced as the third baseman picked for the various all-time teams selected by famous ballplayers and sportswriters. When The Sporting News published a long biographical sketch of Collins in 1933, the baseball weekly reinvigorated the fabled 1895 story about his exceptional fielding of bunts by the infamous Baltimore Orioles.8 Ten years later this legend became the centerpiece of a campaign to put Collins in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Collins’s real-estate business reached its zenith of prosperity during World War I, before suburban flight in the 1920s changed the neighborhood, real estate prices peaked in 1926, and then mortgage defaults during the Great Depression resulted in property foreclosures. In 1927 Collins sold his home; he and his wife began renting apartments, before they moved in with their oldest daughter, Kathlyn. By 1935 Collins’s real-estate business had imploded and he earned an income as an employee in the Buffalo Parks Department. Despite his financial reversals, Collins continued to gracefully serve as an ambassador for Buffalo athletics in his unpaid role as muni-league president.

Collins died on March 6, 1943, in Buffalo and was buried in Holy Cross Cemetery. Two months before Collins passed away, Buffalo Evening News sports editor Bob Stedler began a press campaign to have Collins elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame at the next BBWAA election in January 1945. Even with a heavy dose of electioneering by Stedler, Collins polled only 49 percent of the vote, far short of the required 75 percent. But that spring the Old-Timers Committee unanimously selected Collins for enshrinement in the Hall of Fame.

Jimmy Collins’s legacy in baseball is much more than his batting and fielding exploits during the Deadball Era. As a star player, first manager, and the public face of the nascent Boston Americans, Collins put the franchise, valued by Forbes in 2012 at $1 billion, on a solid foundation. He delivered two pennants in the team’s first four years and victory in the 1903 World Series, and thus should be remembered as the patron saint of today’s Red Sox Nation.

An updated version of this biography appeared in “The Glorious Beaneaters of the 1890s” (SABR, 2019), edited by Bob LeMoine and Bill Nowlin. This biography also appeared in “New Century, New Team: The 1901 Boston Americans” (SABR, 2013), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted:

O’Connell, Fred. “Boston’s Baseball Idol: Jimmy Collins, Manager and Captain of the World’s Champion Club.” Washington Post, September 11, 1904.

Stedler, Bob. “Jimmy Collins, Buffalo’s Baseball Immortal, Dies,” Buffalo Evening News, March 6, 1943.

Notes

1 Cy Kritzer, “Late Jimmy Collins, the ‘King of Third Sackers,’ Became Hot Corner Star by Ability to Handle Bunts,” The Sporting News, March 11, 1943.

2 Charlie Bevis, Jimmy Collins: A Baseball Biography (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2012), 33-35.

3 Boston Globe, March 10, 1901.

4 Bevis, Jimmy Collins, 113, 120-121.

6 Tim Murnane, “His Winter Pastime Collecting Rents,” Boston Globe Magazine section. January 15, 1905.

7 Buffalo Express, December 6, 1922.

8 “Daguerreotypes: James J. (Jimmy) Collins,” The Sporting News, July 27, 1933.

Full Name

James Joseph Collins

Born

January 16, 1870 at Niagara Falls, NY (USA)

Died

March 6, 1943 at Buffalo, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.