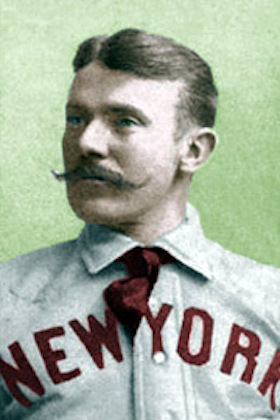

John Montgomery Ward

No essay-length biography could possibly do full justice to John Montgomery Ward. His life, both on and off the diamond, was entirely too eventful. His playing career was replete with notable achievements. When he joined the Providence Grays in 1878, an 18-year-old Ward was the National League’s youngest player. During the 1880 season, he hurled the circuit’s second perfect game after having been the NL’s winningest pitcher the season before. When overuse and injury ruined his throwing arm, Ward, an exceptional athlete, transformed himself into a capable everyday player. He shortstopped the New York Giants to consecutive world championships in 1888-1889, and five years later led the Giants to a postseason Temple Cup triumph as player-manager. Nor did Ward abandon baseball after his retirement from playing in 1894. During his later years, he stood as a controversial candidate for the National League presidency; was club president and part-owner of the Boston Braves; and served in the front office of the Brooklyn franchise in the upstart Federal League.

No essay-length biography could possibly do full justice to John Montgomery Ward. His life, both on and off the diamond, was entirely too eventful. His playing career was replete with notable achievements. When he joined the Providence Grays in 1878, an 18-year-old Ward was the National League’s youngest player. During the 1880 season, he hurled the circuit’s second perfect game after having been the NL’s winningest pitcher the season before. When overuse and injury ruined his throwing arm, Ward, an exceptional athlete, transformed himself into a capable everyday player. He shortstopped the New York Giants to consecutive world championships in 1888-1889, and five years later led the Giants to a postseason Temple Cup triumph as player-manager. Nor did Ward abandon baseball after his retirement from playing in 1894. During his later years, he stood as a controversial candidate for the National League presidency; was club president and part-owner of the Boston Braves; and served in the front office of the Brooklyn franchise in the upstart Federal League.

As impressive as these achievements are, they are nonetheless overshadowed by Ward’s contributions to the game as a trailblazer. Intelligent, well educated, and dynamic, Ward organized the first major-league players union in 1885 and was a tireless advocate for players’ rights. He also authored the first popular How-To manual for youngsters wishing to take up the game. But first and foremost, Ward is remembered as the driving force behind the employee-controlled Players League, the audacious but short-lived challenger to the preeminence of the National League and American Association. Apart from all this, he also took an active role in the social and civic life of greater Gotham. At various times, Ward was a high-visibility Broadway bon vivant, a distinguished New York City attorney, a Long Island country squire and community pillar, and a major figure in Northeastern amateur golfing circles. Although there are other worthy contenders for the laurel, John Montgomery Ward may well have been the most accomplished man ever to play major-league baseball. And when it finally came in 1964, his posthumous induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame was both well-deserved and long overdue.

The multifaceted Ward was born on March 3, 1860, in Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, a tranquil village located in the Nittany Valley, about 12 miles northeast of the Agricultural College of Pennsylvania (now Pennsylvania State University). He was the second of the three children born to James Ward (c.1806-1871), and his third wife, the former Ruth Hall (1826-1874).1 The Ward clan was of English stock, descended from mid-1600s Connecticut settlers, while the Hall family was long-established in Bellefonte. James Ward and his brother Philoh (who married another Hall sister) were recent arrivals in Bellefonte, where they became the proprietors of a machine shop that produced threshers and other farming equipment. Unusual for a married woman of her time, Ruth Ward was also employed, teaching at a public elementary school in Bellefonte. In his youth, Monte,2 as he was called by family and hometown acquaintances, was raised in a comfortable, pious Presbyterian household and attended village schools.

Tragedy struck the family in 1871. First, Monte’s father died of consumption. Months later, his half-brother James Moore Ward, a divinity student, was killed in a railway accident. For a time, Ruth Ward, by now elevated to the post of school principal, managed. But in December 1874, she was stricken with pneumonia and died, orphaning her two sons. Older sibling Charles was taken in by his Uncle Philoh, but not Monte. At age 14, he was dispatched to Penn State, which, like many other colleges, also maintained a prep school for younger students. Here, as Johnny Ward, he first attracted public notice. In the spring of 1875, Ward, a member of Penn State’s first baseball team, astounded several thousand onlookers on the Old Main Lawn by demonstrating that a thrown ball could actually be made to curve.3 By then he was already an established pitcher in local circles, having begun as a youngster in Bellefonte, before graduating to an amateur club in Lock Haven. The following year, Ward’s time at Penn State came to an abrupt halt. A midnight caper involving the theft of chickens from a nearby farm led to his expulsion from school.4

Now largely on his own, the youngster eked out an existence peddling nursery plants. His sales route took him through the Allegheny Mountains and included a stop in Renovo, Pennsylvania. There, Ward tried to supplement his meager salesman’s wage by pitching for the borough’s semipro team, the Resolutes. The club promised him $15 a month plus board, but ultimately stiffed him on payment.5 That experience notwithstanding, Ward decided to pursue baseball as his calling. The 1877 season saw him in action for at least five clubs: an independent team in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, followed by League Alliance clubs in Philadelphia (the Athletic and the Philadelphias, aka Phillies), Janesville, Wisconsin, and Buffalo.6 In most instances, the clubs disbanded shortly after Ward’s arrival. Still, he remained undiscouraged, beginning the 1878 season with yet another League Alliance team: the Binghamton (New York) Crickets. Here, history repeated itself, as the Crickets folded in early July. Little statistical evidence of Ward’s performance survives,7 but he must have impressed. Days after the Binghamton club went under, 18-year-old Johnny Ward became a major leaguer, signing with the Providence Grays of the National League as a replacement for defecting pitcher Tricky Nichols.

Ward made his major-league debut on July 15, 1878, dropping a 13-9 decision to the Cincinnati Reds in a contest marred by slipshod defense on both sides. One game account stated: “Ward belongs to that class of pitchers who turn their backs to home plate and send in the ball after a quick turn. … His delivery is of questionable legality, his hand moving some distance above the hip in forward motion.”8 Whether strictly legal or not, right-hander Ward’s sidearm slants were in regular use thereafter. He pitched every one of the 34 games remaining on the Providence schedule, posting a commendable 22-13 record, with a retroactive NL-leading 1.51 ERA in 334 innings pitched, for the third-place (33-27) Grays. Ward’s batting (.196 BA), however, was a different matter and in need of improvement.

Baby-faced and still shy of his full adult stature (officially 5-feet-9/175 pounds, but probably smaller), Ward blossomed in his sophomore campaign. He posted a 47-19 record, pitching a herculean 587 innings. Ward led the National League in victories, winning percentage (.712), and strikeouts (239). He also played capably at third base and in the outfield when occasionally spelled in the box by Bobby Mathews (12-6). And his bat came to life, as well. Hitting from the right side,9 Ward batted a solid .286, with 41 RBIs in 83 games. With shortstop-manager George Wright supplying leadership and the outfield duo of Paul Hines (.357) and Jim O’Rourke (.348) the offensive punch, Providence (59-25) captured the NL pennant by five games over runner-up Boston. That offseason, Ward remained in town managing a Providence sporting emporium. He returned to the Grays the following season, but Wright and O’Rourke had left the club. Early in the season, now 20-year-old Johnny Ward replaced Mike McGeary as manager, guided the Grays to an 18-13 record, and was then replaced himself by Mike Dorgan. Despite turmoil at the helm, Providence (52-32) made a respectable defense of its league crown, finishing second to a (67-17) Chicago juggernaut.

Key to Providence fortunes was the performance of pitching ace Ward. He posted a 39-24 record, with a sparkling 1.74 ERA in 595 innings pitched. Ward struck out 230 batters and posted a league-leading eight shutouts, as well. A personal highlight had occurred in a rare morning game on June 17. Ward retired all 27 Buffalo batters he faced in a 5-0 victory, registering only the second perfect game in big-league history.10 But by now the overuse of his young right arm was beginning to take its toll, and Ward would never again approach these kinds of pitching heights. Nor, incidentally, would his appearance remain the same. Over the ensuing winter, Johnny began to cultivate the luxuriant mustache that would become a trademark for the rest of his life.

Beginning in 1881, Ward began transitioning into a position player. That year, he spent more time at shortstop and in the outfield (52 games) than he did in the pitcher’s box (39), but was no great shakes at either. He batted a mild .244, while going 18-18 as a pitcher for another runner-up Providence club. The following season was pretty much the same. Ward split time between field positions and the pitcher’s box, batting a soft .245 (only 14 of his 87 base-hits went for extra bases) and posting a 19-13 pitching log for the once again second-place Providence Grays. He seemed stuck in a rut, but fate was now about to smile on John Montgomery Ward.

Prior to the 1883 season, Ward was among the talented young players acquired by cigar manufacturer John B. Day for the clubs he was placing in the National League and its new rival, the American Association. Along with future Hall of Famers Buck Ewing, Roger Connor, and Mickey Welch, Ward was assigned to the NL Gothams (soon-to-be Giants).11 By now, Ward had come a long way from the mischievous teenager cashiered from Penn State. He had matured into a serious man with serious ambitions — in baseball and beyond. And New York was the perfect fit for them.

To cure the deficiencies in his education and with his post-baseball future in mind, Ward began taking night and offseason classes at the prestigious Columbia College [now University] School of Law. Handsome, refined, immaculately tailored, and single, he also cut something of a figure in society, often spending evenings at the theater or in Manhattan drawing rooms. But for the short term, Ward still concentrated on playing baseball. During the 1883 season, he alternated between the outfield and the pitcher’s box, batting .255 and going 16-13 as the club’s number-2 starter behind Welch (25-23) for the sixth-place (46-50) Gothams.

The following season was a challenging one for Ward. An early-season injury to his right arm caused by a slide on the basepaths brought his pitching career irrevocably to its end.12 To bolster his offensive output (and to lessen an admitted fear of being hit by pitches), Ward converted to batting left-handed. And he was spending more time in the infield than before (47 games at second base compared with 59 in the outfield). All the while, Ward was the club’s field leader, having replaced Buck Ewing as New York captain (the first of many events that would strain the relationship between the two). By season’s end, he was also the Gothams’ manager, predecessor Jim Price having been dismissed from club employ after having been caught embezzling club funds for a second time.

The year 1885 was a watershed for Ward, as he began to transcend being just a ballplayer. On the field, Ward was one of the weaker offensive links (.226 BA) in a New York lineup fortified by the acquisition of another future Hall of Famer, Jim O’Rourke, and former Mets star Dude Esterbrook, obtained along with Mets pitching ace Tim Keefe via some rule-bending chicanery by Metropolitan Exhibition Company boss John B. Day.13 Ward compensated for his poor bat by adapting successfully to the demanding position of shortstop and by heady field leadership. The Giants14 soared to an 85-27 (.759) record, only to be outdone by the Cap Anson/King Kelly/John Clarkson Chicago White Stockings, who finished two games better.

The larger destiny that awaited Ward was augured by the law degree that he had received from Columbia in May. While he would not practice law for another 10 years, Ward promptly put his legal training to good use. Along with teammates Jim O’Rourke, Tim Keefe, Roger Connor, and Buck Ewing — all, like Ward, sober, intelligent men — and others, he founded the first serious ballplayers union, the Brotherhood of Professional Baseball Players. Over the next five years, Ward would use his keen intellect, legal understanding, and fluid pen to air union grievances about the one-sidedness of the club owner-ballplayer relationship. In time, these were embodied in a magazine article entitled Is the Base-Ball Player a Chattel?, an incisive deconstruction of the Reserve Clause that gained widespread circulation.15 Growing in public prominence and the subject of much sports-page ink, Ward became, in relatively short order, the most important player in major-league baseball, wielding power and influence over National League stars and journeyman players alike, almost all of whom had become members of the Brotherhood, which Ward led.16

Ward burnished his post-baseball resume with another academic degree, a Ph.B. in philosophy awarded by Columbia’s School of Political Science in 1886.17 But soon thereafter, Ward entered an entirely different venue — the world of celebrity culture, late-19th-century style. The vehicle: his courtship of the renowned stage actress Helen Dauvray. Born Ida Louise Gibson, Dauvray had been entertaining theater audiences since childhood, and was probably several years older than Ward. Small, ambitious, business-minded, and divorced, Helen was a great baseball fan and the donator of the Dauvray Cup, bestowed on the champion baseball teams of the late 1880s.18 Ward and Dauvray were married in October 1887, but their union was a fragile one, jeopardized by their willful personalities, frequent profession-related separations, and Ward’s infidelities.19 The couple repeatedly quarreled, separated, and finally divorced in 1893. They had no children.20

Meanwhile, back at the Polo Grounds, Ward was maturing into a fine everyday player. Shortstop proved a congenial position, and he excelled there defensively. Ward’s hitting also began to pick up. In 1886 he batted a solid .273, with a career-best 81 RBIs. The next season he skyrocketed to a walks-inflated .371 (later adjusted to a still-impressive .338),21 with 114 runs scored and an eye-catching 111 stolen bases, then an NL record. He also played well in the field, his .919 fielding average being tops among NL shortstops. Notwithstanding Ward’s contributions, the club was headed in the wrong direction, amid reports of internal strife involving its team captain. Cool and with an innate aura of superiority about him, Ward was respected, but never much liked by teammates. Several were reportedly not even on speaking terms with him. With New York on the way to an underachieving fourth-place finish, Ward was replaced or resigned — accounts differed — as Giants captain midway through the 1887 campaign, with Buck Ewing re-installed in the post. That offseason, Ward salved his pride by authoring the first popular instructional for budding baseball players, Base-Ball: How to Become a Player, with the Origin, History and Explanation of the Game.22

Ward remained at shortstop while the talent-laden Giants finally jelled. They captured consecutive National League pennants in 1888 and 1889, and bested the American Association champ in each postseason match to claim the title of world champions. Ward was at his offensive best during these series, batting .379 and .417, respectively. But all was not well in the baseball world, and John Montgomery Ward, predictably, was at the center of the unrest. As leader of the players union, Ward had long been sparring with NL club owners over the reserve clause. Hard feelings were exacerbated when the league adopted the player-classification plan proposed by Indianapolis owner John T. Brush. Under this scheme, players were assigned a classification (A through E) based upon subjective owner evaluation of their performance, value to the club, and deportment, with rigid and niggardly salary limits imposed for each classification. Perhaps not entirely coincidentally, the Brush plan had been crafted and adopted by the league while players union president Ward was out of the country and largely incommunicado as a member of the celebrated world tour arranged by Chicago White Stockings boss A.G. Spalding. Upon his return in March 1889, the classification plan was already in place, and there was little that Ward could do — for the time being. But he soon devised a radical remedy — creation of an entirely new baseball league, one controlled by its players.

A history of the Players League is beyond the scope of this biography. Suffice it to say that the circuit was almost entirely the product of Ward’s energies. Among other things, he orchestrated the recruitment of financial investors in the Players League; found playing sites for its franchises; guided the members of his players union, almost all of whom jumped to the new league, onto their new clubs; arranged the Players League schedule, and dealt daily with the myriad organizational problems confronting the venture — all the while successfully fighting off National League efforts to suppress player movement toward the new circuit via enforcement of the reserve clause. Ward, Jim O’Rourke, Roger Connor, and others were hauled into court by Giants owner John B. Day, but in each instance, the court declined to enjoin the players from plying their trade elsewhere. The talent imbalance soon became obvious, as virtually all the NL stars, and a few prominent American Association players, as well, had joined a Players League team.

Nowhere was the situation more striking than in New York, where only Mickey Welch and outfielder Mike Tiernan remained with the NL Giants. The Players League Giants had O’Rourke, Connor, Tim Keefe, Buck Ewing, and the rest of 1889 world champs — save Ward. John M. (as he preferred to be called) placed himself across the East River as player-manager of the Brooklyn PL club. Competition at the gate was cutthroat, no more so than in New York, where the PL Giants ballpark (Brotherhood Park) was separated from the NL Giants ballpark (Polo Grounds II) by no more than a 10-foot alley. With three major leagues in operation simultaneously, there simply were not enough fans to go around, and clubs soon hemorrhaged red ink. Even before the 1890 season ended, NL Giants owner Day and his PL counterparts were in merger discussions. Thereafter, the hard-nosed A.G. Spalding hammered other PL backers into surrender, the protests of Ward, excluded from the negotiating table, being dismissed by NL and PL club owner alike.23 Before the year was out, the Players League had expired, passing into baseball history.

Perhaps ironically, Ward had had his best all-around season in 1890, batting .335, with career-high marks in runs scored (134), on-base percentage (.393), and slugging (.426). He also stole 63 bases and led PL shortstops in assists (450). With the Players League dead and the American Association dying — the AA would fold at the close of the 1891 season — Ward rejoined the National League, but remained in Brooklyn, piloting the club to also-ran finishes during the 1891 and 1892 seasons. At times it was rumored that Ward, who had acquired a small stake in the Giants franchise, had his eye on ownership of the financially troubled New York club. But when he returned to the Giants in 1893, it was in the role of second baseman and manager. Upon arrival, Ward’s first move stunned the New York faithful. He shipped Buck Ewing, an aging Giants icon with whom Ward had always had an uneasy relationship, to Cleveland in exchange for a promising outfielder-infielder named George Davis. The move would prove an astute one, as Ewing had only one outstanding season left in him, while Davis would provide New York with 10 seasons of brilliant offense and defense. Davis and Ward would also become good friends, but the relationship would prove the source of much grief for Ward in his post-baseball life.

Ward’s final two major-league campaigns were filled with achievement. In 1893 he posted an outstanding .328/.379/.415 slash line, with 129 runs scored and 46 steals. The following year, he guided the Giants to an 88-44 second-place finish, and thereafter a four-game sweep of the pennant-winning Baltimore Orioles in the postseason Temple Cup match. He then announced his retirement. In 17 major-league seasons, John Montgomery Ward had been something of an anomaly: a good, if not great, performer as both a pitcher and a position player; only the incomparable Babe Ruth would surpass him as a combination pitcher-turned-everyday player. Ward had gone an impressive 164-103 (.614) as a hurler, with a 2.10 ERA in almost 2,500 innings pitched. He had been a competent .275 singles hitter (almost 84 percent of his 2,107 career base hits), an exceptional baserunner and run scorer, and a capable defender, particularly at the demanding position of shortstop. In six-plus seasons as a major-league player-manager, Ward guided his teams to a 412-320 (.563) mark, with a triumph in one postseason championship match. And almost singlehandedly, he had founded a bona-fide, albeit short-lived, major league. All in all, Ward had had a distinguished baseball career.

Approaching age 35, Ward embarked on the legal practice that he would maintain for the rest of his life. He began by clerking for a well-to-do-corporate lawyer named Austin Fletcher while he boned up for the New York bar examination.24 Ward passed the exam and was licensed to practice in July 1895.25 He set up his own law office in Brooklyn, and soon the connection to baseball supplied business to the fledgling barrister. First, second baseman Fred Pfeffer, and then fireballer Amos Rusie, engaged Ward to sue Andrew Freedman, the tempestuous new owner of the New York Giants.26 These high-profile suits did much to establish Ward’s credentials as an attorney, and his practice flourished.

When not building up his legal practice, Ward was consumed by a new passion: golf. Despite his age and relatively late start in the game, the athletically gifted John M. quickly developed into a links master, winning a local tournament in 1897.27 By 1903, he was among the nation’s top amateurs, runner-up in the North-South Tournament, then one of American golf’s premier events. That year also saw Ward’s marriage to Katherine Waas, a vivacious Manhattan social worker some 17 years his junior. The couple had first met on the golf course, and were pronounced husband and wife within months. The union would prove a long-lasting and happy one, but childless. Another event that came to a head in 1903, however, would not prove such a felicitous one for Ward: the George Davis affair.

The matter is complicated. But in brief, Ward had counseled his friend Davis and entered modifications on the two-year contract that Davis had signed when he jumped to the Chicago White Sox after the 1901 season. A year later, Davis was back in the office seeking Ward’s help to break that contract and jump back to the Giants. When Davis appeared in uniform for New York in early 1903, White Sox owner Charles Comiskey sought federal court intervention. At the ensuing proceedings, Ward offered the legal opinion that both the White Sox contract and the Giants contract were valid, and that Davis could take his pick as to which one to honor. To no great surprise, this kind of doublespeak did not play well in court. Worse yet was reaction in the court of public opinion, with baseball voices leading the chorus of disapproval. “Great is the power of the retaining fee over the legal mind,” observed The Sporting News. “It can make black appear white and vice versa in a twinkling.”28 Chicago Cubs president James Hart characterized Ward’s reasoning as ‘trumped up” and liable to “ruin his standing with any reputable bar association,”29 while American League President Ban Johnson denounced Ward as a “trickster” and “as crooked as any player who ever jumped his agreement.”30 In the end, the court ordered Davis’s return to Chicago, where he was welcomed back by Comiskey and completed his Hall of Fame playing career there without incident. Not so fortunate was John Montgomery Ward, for whom the George Davis affair would produce long-term consequences.31

As he grew older, Ward became more conservative. Now instead of ballplayers, he sometimes represented the game’s establishment, even defending in court the validity of the reserve clause that he had once reviled. But for the most part, Ward’s practice gravitated toward the corporate world, with the Nassau Railway Company and public utilities being favored clients. Then in mid-1909, events thrust Ward back into the baseball limelight. The July 28 suicide of Harry Pulliam created an unexpected vacancy in the office of National League president, and John Montgomery Ward quickly emerged as a leading candidate for the post. Although he had no official role to play in the election, AL President Ban Johnson loudly intruded into the process, declaring that his league would not sit in council with the NL if Ward were its president. His conduct in the George Davis affair disqualified Ward from consideration for the NL presidency, in Johnson’s opinion.32 As it turned out, National League club owners did not give a hoot what Johnson thought, but the election vote repeated stalemated 4-4 between Ward and Louisville newspaperman Robert Brown over other issues. When NL umpiring chief Tom Lynch was finally proposed as a compromise candidate, Ward withdrew from the race gracefully, and endorsed Lynch’s election.

Tom Lynch was unanimously elected NL president, but the matter did not rest there. Smarting from the public aspersion cast upon his character, Ward filed a $50,000 defamation suit against Ban Johnson. The action was tried in federal court, where Ward came off as the stereotypical shifty lawyer on the witness stand. Fortunately for him, Johnson was worse, a pompous blowhard who probably perjured himself during his testimony. In the end, the jury returned a modest $1,000 judgment in Ward’s favor, but the suit had done little credit to the reputation of either party.33 The unpleasantness notwithstanding, the episode seemed to rekindle Ward’s interest in baseball, at least temporarily. In December 1911, he became part-owner and president of the National League Boston Braves. But less than a year later, Ward stepped down, citing the press of his legal practice. By doing so, he missed out on the glory of the Miracle Braves’ improbable 1914 world championship. By then Ward was tending to his final baseball-connected job: business manager of the Brooklyn club in the upstart Federal League. His retirement from that post in April 1915 brought a near-40-year association with the game to an end.

Ward spent the final decade of his life as a gentleman farmer on Long Island, residing on the 200-acre tract in North Babylon where he and Katherine had lived since their marriage in 1903. The couple regularly attended Sunday services at St. Ann’s Episcopal Church and were active in local social and civic affairs. As the years went by, John M. spent less and less time at his law office in Brooklyn and more time tending to the affairs of the ice company, fuel company, and newspaper (Babylon Leader) he had started. He also became a member of various fraternal orders, and served as a fishing conservation trustee. In addition, Ward was the founder and first president of the Long Island Golf Association, and continued to play the game at a high level until the end of his life, winning the Nassau County Championship at age 62. 34 He also hunted, fished, and traveled extensively. In March 1925, one such expedition preceded his demise. While on a hunting trip in Georgia, Ward was stricken by a recurrence of the pneumonia that had weakened his health for the previous three years. He died of acute lumbar pneumonia at a hospital in Augusta on March 4, 1925, the day after his 65th birthday. Following funeral services at St. Ann’s Church, he was interred at Greenfield Cemetery in Hempstead, Long Island. The only immediate survivor was his wife, Katherine.35

When the Hall of Fame opened its doors in the late 1930s, John Montgomery Ward attracted negligible support (three votes in 1936). In 1946 Ward was among 39 major-league managers, executives, umpires, and sportswriters named to the Honor Rolls of Baseball, a second-class admission into Cooperstown that promptly receded into oblivion.36 But in 1964 — 70 years after he had last played the game and nearly 40 since his death — Ward was a Veterans Committee choice for full enshrinement. Today, the Hall of Fame plaque for John Montgomery Ward lists his statistics and then states simply: “Played an important part in establishing modern organized baseball,” better capturing in a phrase the legacy that this bio has taken some 6,000 words trying to memorialize.

This biography is included in “20-Game Losers” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Emmet R. Nowlin.

Sources

Sources for the biographical details provided herein include the John Montgomery Ward file maintained at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; biographies by Brian DiSalvatore, A Clever Base-Ballist: The Life and Times of John Montgomery Ward (New York: Pantheon Books, 1999), and Dan Stevens, Baseball’s Radical for All Seasons: A Biography of John Montgomery Ward (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1998), and various of the newspaper articles cited below. Unless otherwise noted, statistics have been taken from Baseball-Reference and Retrosheet.

Notes

1 Ward’s full siblings were Charles Lewis Ward (1855-1906) and a younger sister named Ida who died a week after her birth. He also had a half-sister named Mary Caroline (c.1840-1907), and a deceased half-brother named William, the children of his father’s late first wife, Caroline (maiden name unknown). He also had a half-brother named James Moore Ward (1846-1871), the sole child of his father’s late second wife, Ellen Moore. For more on the extended Ward family, including its distant connection to the famous retail entrepreneur A. Montgomery Ward, see DiSalvatore, 25-30.

2 In the 1870 US Census, Ward is listed as Montgomery, a name he detested, according to biographer DiSalvatore. He tolerated Monte, but that nickname was reserved for family and childhood acquaintances. Monte never appeared in newsprint during Ward’s lifetime. In his early baseball years, teammates, fans, and the sporting press usually called him Johnny Ward. As he matured and his stature grew in the game, he became John Ward, and occasionally the grander John Montgomery Ward in newsprint. But the vast majority of the time, sports pages recorded the exploits of John M. Ward, the name that Ward preferred and the one that he used for his signature. See DiSalvatore, 19-24.

3 As recounted by Geoff Rushton in “Did You Know: Baseball Pioneer Got His Start at Penn State,” Penn State Live, June 20, 2006.

4 For more detail on the events that precipitated Ward’s expulsion, see DiSalvatore, 56-58.

5 According to Hugh Manchester, “Bellefonte Claims ‘Hall of Famer,’” The (Bellefonte) Centre Democrat, an undated circa 1959 news article contained in the Ward file at Cooperstown.

6 As per Sam Crane, “The Fifty Greatest Baseball Players in History: No. 29, John M. Ward,” New York Journal, February 22, 1912. See also, “John M. Ward, Pitcher,” The New York Clipper, September 6, 1879.

7 Without specifics, one Ward biographer puts his overall pre-major-league pitching record at a pedestrian 28-28. See Stevens, 11.

8 Cincinnati Daily Gazette, July 16, 1878.

9 Baseball reference works invariably list Ward as a left-handed batter, but he did not become one until the 1884 season. For his first six major-league seasons, Ward batted as he threw: right-handed.

10 Only five days earlier, the first perfect game had been thrown by Worcester southpaw Lee Richmond.

11 Day had obtained Ewing, Connor, Welch, and Tim Keefe in the fire sale of the defunct NL Troy Trojans. For the time being, however, Keefe was assigned to Day’s American Association club, the New York Metropolitans. Technically, both the NL Gothams and the AA Mets operated under the aegis of the Metropolitan Exhibition Company, Day’s corporate alter ego.

12 Prior to the injury, Ward had gone 3-3, pitching in nine games.

13 The maneuvers that brought Esterbrook, Keefe, and Mets manager Jim Mutrie into the Gothams/Giants fold are described in the BioProject profile of John B. Day.

14 The nickname Giants traces to the 1885 season, and is customarily attributed to newly installed manager Jim Mutrie. The originator of the moniker, however, may well have been New York Evening World sportswriter P.J. Donahue. For more, see the BioProject profile of Mutrie.

15 First published in Lippincott’s Magazine, August 1887.

16 The Brotherhood had concentrated on getting National League players to join. Few American Association players were in its ranks.

17 Ward later maintained that both his law and philosophy degrees came with honors, but a century later, officials at Columbia could not confirm this for the writer, as per email of Jody Armstrong, associate director, Arthur W. Diamond Law Library, Columbia University, dated February 26, 2008.

18 For more on Helen, Ward, and the long-missing Dauvray Cup, see John Thorn, “Baseball’s Lost Chalice,” in Base Ball, A Journal of the Early Game, Vol. 5, No. 2 (Fall 2011), 84-96.

19 For an entertaining, if fictionalized, account of Ward’s dalliance with the actress Maxine Elliott (née Jessie Dermot), see James Hawking, Strikeout: Baseball, Broadway and the Brotherhood in the 19th Century, (Santa Fe, New Mexico: Sunshine Press, 2012), 191-193.

20 Interestingly, Tim Keefe, Ward’s teammate and fellow union stalwart, married Helen Dauvray’s sister, Clara Gibson Helm. That marriage, too, was childless and ended in divorce.

21 For the 1887 season only, walks were counted as base hits for batting-average purposes.

22 Released under the byline of John Montgomery Ward in 1888, the instructional was reprinted by SABR in 1993, and is now available as a free e-book to SABR members. Biographer DiSalvatore maintains that the book represented the sole time that Ward consented to use of his disliked middle name by a publisher.

23 In response to vocal complaints by Ward about the merger of the two New York clubs, de facto PL Giants boss Edward B. Talcott tartly informed the press, “I don’t propose to have Mr. Ward or anybody else criticize my business methods. Nor shall I allow Mr. Ward to tell me how my financial interests must be arranged. The fight cannot go on for another year, for baseball will become a dead sport. Ward can say what he likes but it cannot alter matters with us a particle.” Chicago Tribune, November 7, 1890.

24 Per Stevens, 181.

25 As reported in the New York Times, July 20, 1895.

26 Freedman had acquired majority control of the Giants in late January 1895, an event often cited as the reason for Ward’s retirement from the game. This is incorrect, as Ward had announced his intention to begin the practice of law months before Freedman’s name surfaced as a bidder for the New York franchise. More to the point, Ward approved Freedman’s entry into the game, selling him his small holding of club stock and endorsing Freedman’s initial moves as Giants boss, particularly the naming of Ward protégé George Davis as Giants manager. Like A.G. Spalding, another future Freedman nemesis, Ward initially believed that the deep-pocketed Freedman was just the man the financially troubled New York franchise needed, and only soured on him later.

27 See Stevens, 199-200.

28 The Sporting News, April 18, 1903.

29 As quoted in Sporting Life, March 18, 1903.

30 Sporting Life, April 11, 1903.

31 A more expansive account of the George Davis affair is provided by the writer in “The Ward v. Johnson Libel Case: The Last Battle of the Great Baseball War,” in Base Ball, A Journal of the Early Game, Vol. 2, No. 2 (Fall 2008), 50-52.

32 The Johnson broadside was first published in the Chicago Tribune, November 28, 1909, and reprinted in newspapers nationwide.

33 For more on the proceedings, see Lamb, 54-61.

34 As noted by Natalie A. Taylor in “Long Island’s Gentleman Athlete: John Montgomery Ward,” undated circa 1990 article from The Nassau County Historical Society Journal contained in the Ward file at Cooperstown. See also the Babylon (New York) Leader, March 6, 1925.

35 Katherine Waas Ward died in 1966, at 79. She was buried next to her husband.

36 For more on this long-forgotten laurel, see David L. Fleitz, “The Honor Rolls of Baseball,” Baseball Research Journal, No. 34, 2005, 53-59.

Full Name

John Montgomery Ward

Born

March 3, 1860 at Bellefonte, PA (USA)

Died

March 4, 1925 at Augusta, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.