Johnny Morrison

Johnny Morrison had one of the deadliest, most knee-locking curveballs baseball had ever experienced. “You simply couldn’t see it,” raved contemporary Pat Duncan. “The ball came in like a fast ball and it dropped so fast that it fell completely out of your vision unless you were looking for such a hook.”1 That pitch became known as the Jughandle and catapulted “Jughandle Johnny” to a successful five-year run with the Pittsburgh Pirates, including a 25-win season in 1923 and a World Series championship two years later. But Jughandle also had another meaning for Morrison, whose 10-year major-league career was fraught with as much tension and conflict as triumph and personal glory.

Johnny Morrison had one of the deadliest, most knee-locking curveballs baseball had ever experienced. “You simply couldn’t see it,” raved contemporary Pat Duncan. “The ball came in like a fast ball and it dropped so fast that it fell completely out of your vision unless you were looking for such a hook.”1 That pitch became known as the Jughandle and catapulted “Jughandle Johnny” to a successful five-year run with the Pittsburgh Pirates, including a 25-win season in 1923 and a World Series championship two years later. But Jughandle also had another meaning for Morrison, whose 10-year major-league career was fraught with as much tension and conflict as triumph and personal glory.

John Dewey Morrison was born on the family farm in Pellville, a hamlet with about 70 residents in Hancock County, located in northwestern Kentucky, near the border with Indiana. He was the oldest of five children born to Arreatus and Palestine (Ford) Morrison, who married in 1895, and welcomed Johnny into the world on October 22 that same year. According to his player questionnaire, Morrison completed eight years of formal schooling. The elder Morrison became an engineer and eventually relocated the family to nearby Deanefield and later Owensboro, the bustling industrial city on the Ohio River.

It’s uncertain when Johnny began playing baseball, but by the time he was in his late teens he was a well-regarded pitcher and catcher who formed with his hard-throwing brother Phil, two years younger, an imposing battery. By 1915 Johnny was competing in semipro leagues in nearby Evansville, Indiana, where he lived and worked as a truck driver, and the following year in Boonville, where he supposedly won 28 of 30 games.2 According to some sources, Morrison also had a brief encounter with professional baseball from 1915-1917, pitching in a combined 24 games for Anniston in the Class D Georgia-Alabama League; however, the player himself stated that his professional career began in 1919 and ample proof exists to corroborate Morrison’s claim.3

In late May 1918 Morrison was mustered into the US Army and stationed at Camp Zachary Taylor, which had opened the previous year, on the outskirts of Louisville. Morrison rose to the rank of corporal in the 4th Company, 1st Battalion of the 159th Depot Brigade; however, he left his mark as a ballplayer on the camp team and not as an infantryman. One of his teammates was the aforementioned Pat Duncan, who had had a short stint with the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1915, but was at the time a member of the Birmingham Barons of the Class A Southern Association. When Morrison was discharged in March 1919, Duncan arranged with Carlton Molesworth, skipper of the Barons, to give the 23-year-old southpaw a look-see.4

Morrison signed as a free agent with the Barons in 1919 to commence a 14-year run in Organized Baseball. Despite missing spring training, Morrison proved his durability by appearing in a league-high 47 games and posted a sturdy 3.00 ERA in 261 innings; his 12-15 slate reflected the seventh-place Barons’ poor record (59-77). The next season, Morrison emerged as one of the best twirlers in the South, tying for the league lead with 26 victories and racking up 319 innings. Possessing the circuit’s “best curve ball,” Morrison was sold along with teammate Whitney Glazner (24-10) to the Pirates in mid-August, though both pitchers were permitted to finish the Barons season.5

A late-season call-up to the Pirates, Morrison debuted in the second game of a doubleheader against the Cincinnati Reds at Crosley Field on September 28, tossing a hitless inning of relief in a 5-3 loss. Four days later Morrison was involved in a historical matchup at Forbes Field in the Smoky City. In what was described by sportswriter L.H. Wollen as the “first time in the history of the National League that there were three games put on in an afternoon,” Morrison started the third game and tossed a four-hit shutout for his first victory, 6-0.6 [There had been tripleheaders previously in the big leagues; however, the first game had been played in the morning.] The game was called for general fatigue after six innings at 6:00 P.M.

Morrison reported to the Pirates in the spring of 1921, but soon contracted a serious case of influenza and missed the first seven weeks of the season. He finally returned on June 4 and made two relief appearances before the club sent him back to Birmingham on 48-hour recall notice.7 Summoned two weeks later, he joined the team in St. Louis and made “the Cardinals look like rummies” by tossing six scoreless innings of three-hit relief in the second game of a twin bill on June 23.8 Three straight complete-game victories followed in a span of 10 days. Capped off by a 13-inning distance-going affair against the Redbirds in Pittsburgh on July 6, Morrison scattered 13 hits and two runs (one earned) and improved the surprising Pirates’ record to 50-25, four games in front of the eventual pennant-winning New York Giants. Morrison “looks the part of a star,” cooed sportswriter Charles J. Doyle of the Pittsburgh Gazette Times. “Few pitchers who have graced Fogarty Knoll this year have come away with such a glowing victory.”9 [Fogarty Knoll was the moniker of the pitching mound at Forbes Field].

On August 14, Morrison blanked the Cubs on three hits to record his first of 13 career shutouts. With “his wonderful curves flashing,” Morrison tossed another three-hitter two weeks later, defeating the Brooklyn Robins in Ebbets Field, 2-0, to end a Pirates’ six-game losing streak. “Morrison made Burleigh [Grimes] look like a shrimp,” gushed Edward F. Balinger in the Post, while the Pirates’ 2½-game lead over the streaking Giants looked precarious.10 John McGraw’s squad went 24-9 down the stretch, while the runner-up Pirates finished with their best record since 1912. Morrison was a surprise of a strong staff that led the majors with a 3.17 ERA. He completed 11 of 17 starts with a sparkling 2.88 ERA in 144 innings and tied for the league lead with three shutouts.

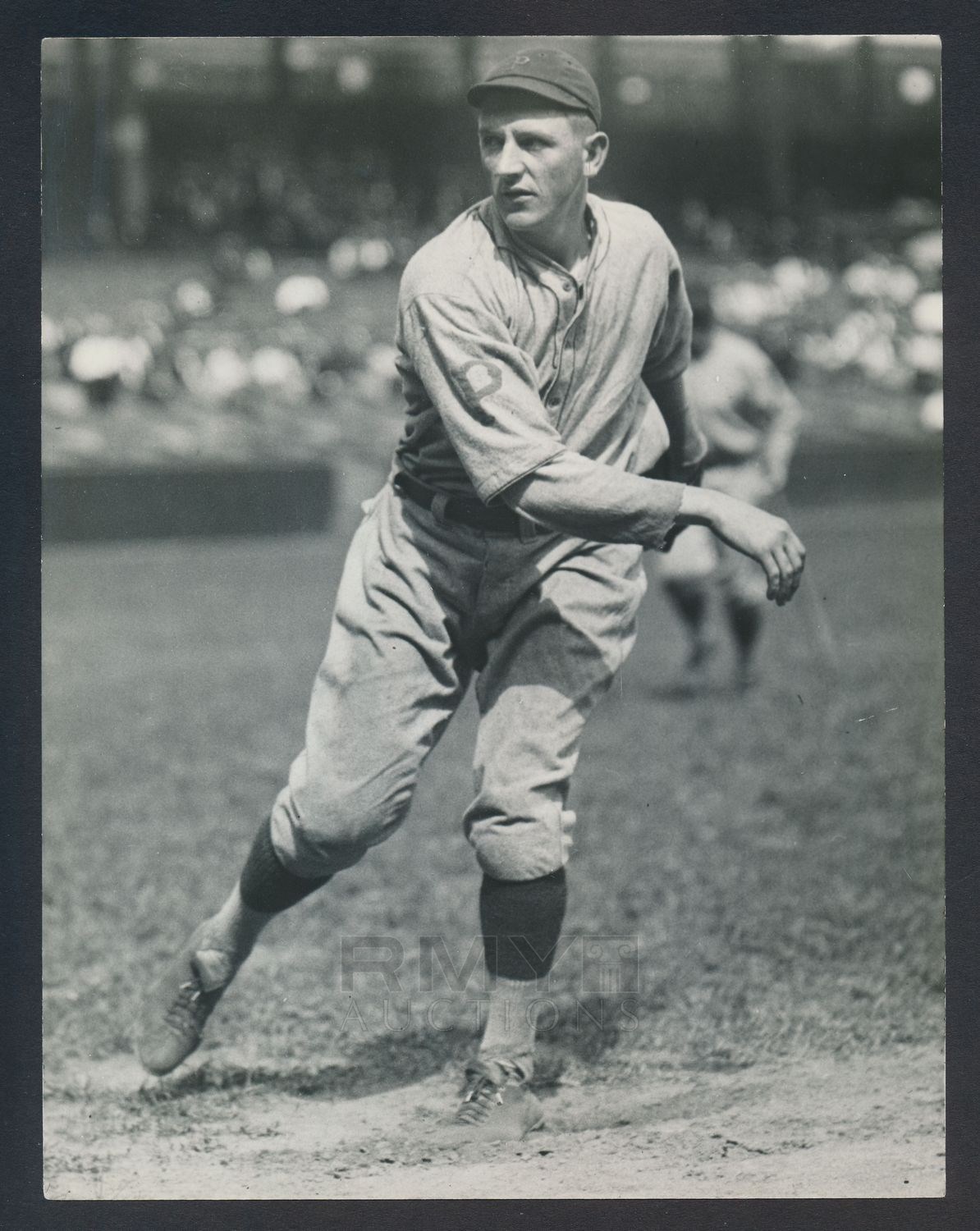

Standing 5-feet-11 and weighing about 165 pounds (he packed on another 25 pounds over the years), Morrison had a deceiving impression on the mound. Beat reporter Charles J. Doyle thought he looked “frail his street clothes,” but noted that he was wiry and muscular.11 Over the next four seasons, Morrison also proved to be a durable, rubber-armed hurler, who could start and relieve.

Morrison was healthy during the Pirates 1922 spring training, which began in New Baden, Indiana, where players took advantage of the natural mineral baths, and then moved to another spa town, Hot Springs, Arkansas. In his first start, Morrison tossed “mean curves over the outside of the plate,” noted sportswriter Jack Ryder of the Cincinnati Enquirer, and “pitched a brilliant game, fooling his opponents … with relative ease.”12 Doyle gushed that “Jughandle Johnny had the Reds looking bad” in his sparkling four-hit, 1-0 victory in the Steel City.13 Once again expected to challenge the reigning World Series champion Giants for the pennant, the Pirates were just a game and a half off the Giants’ lead on June 7 after Morrison hurled a six-hit shutout in Philadelphia. “The Phillies bounced around like grasshoppers in their futile attempts to solve [his curves],” wrote Doyle.14 Scribe Robert W. Maxwell of the (Philadelphia) Evening Public Ledger pronounced Morrison “better than any flinging gent we have seen this year.”15

And then the Pirates’ season took a dive like one of John Dewey’s roundhouse curves. Morrison lost his next eight decisions; the Bucs won just nine of their next 36 games, leading to skipper George Gibson’s replacement by Bill McKechnie. Morrison responded to the 35-year-old McKechnie, the future Hall of Famer and acclaimed horse whisperer to pitchers. Morrison heated up, tossing five consecutive complete-game victories, yielding just six earned runs in 45 frames in 18 days beginning with a four-hit shutout against Phillies. That stretch was highlighted by Jughandle’s whitewashing of the McGrawmen at the Polo Grounds on July 30. Morrison was a lifetime .164 hitter with 84 hits, but did his best Ty Cobb impression in Coogan’s Bluff, whacking four hits, and might have had had his only career homer had a spectator not interfered with a hit that, according to Balinger in the Post, bounced off the top rail in the left-field bleachers and through the fan’s hands and ricocheted back on to the field.16 The umpire ruled it a double despite McKechnie’s protests.

The Pirates went 46-19 beginning on July 15 to erase a 15-game deficit and pull within 3½ games, but the Giants, led by five future Hall of Fame position players (Dave Bancroft, Frankie Frisch, High Pockets Kelly, Ross Youngs, and Casey Stengel), took their second crown. On September 18, Morrison started both ends of a doubleheader against the Phillies, going the distance to win the first game, 11-3, and departed the second with a 2-1 lead after seven innings. Reliever Earl Hamilton surrendered four runs in the eighth to lose the game, 5-2. The Pirates finished in third place while Morrison continued his emergence as one of best hurlers in the senior circuit. He went 17-11, tied for the major-league lead with five shutouts, completed 20 of 33 starts, appeared in a career-best 45 games, and logged 286⅓ innings with a 3.43 ERA.

Morrison reached the pinnacle of his career in 1923. Named Opening Day starter over 23-game winner Wilbur Cooper, Morrison tossed a complete game to subdue the Cubs, 3-2, in Wrigley Field (both runs were unearned) on April 17. Ten days later, he won his third straight start, engaging the Cubs’ Pete Alexander in what Edward F. Balinger described as a “sensational mound duel,” yielding just seven hits in a 2-1 win in the Smoky City.17 By the end of June, Morrison had won three straight starts three times while his 11 victories led the NL. At that point the Pirates were in trailing the front-running Giants by 4½ games in what proved to be a season-long three-team race with the Reds. The Pirates slumped in August and seemed as if they might fall out of contention, losing 13 of 21 games, but Morrison gave the team a big lift on August 20 at the Polo Grounds. His “jug handle curves prove poisonous” to the league leaders, exclaimed the Pittsburgh Post, as Morrison needed just 80 minutes to toss a six-hit, 3-1 victory and keep the Bucs within striking distance, six games back.18

McKechnie leaned on Morrison in September with longtime ace Cooper struggling. In his first of eight starts in just 28 days, Morrison won his 20th game in the morning contest of a Labor Day twin bill at Forbes Field on September 3. The “Kentuckian had his famous curves performing all sorts of capers,” gushed Balinger about Morrison’s six-hitter to defeat the Reds, 7-2.19 Five days later, Morrison tossed a sparkling two-hitter against the Cubs, prompting Lou Wollen of the Pittsburgh Press to exclaim that he “stands out as one of the greatest pitchers that ever wore the Pirates spangles.”20

That victory pushed the Bucs into second, a half-game ahead of the Reds and five behind the Giants; however, the Pirates went 10-13 thereafter to finish in third place (86-68). In the season’s last game at Forbes Field with the Pirates out of contention, Morrison had his “old hook exploding all afternoon,” wrote Charles J. Doyle, to toss the only one-hitter in his career, and also knocked in two runs to hand the lowly Phillies their 100th loss, 6-0.21 Morrison’s 25 victories (13 losses) were surpassed only by the Reds’ Dolf Luque (27); he also finished third in complete games (27), fourth in strikeouts (114), and sixth in innings pitched (301⅔).

Few players in baseball history have had a more appropriate moniker than Morrison’s “Jughandle Johnny.” Pittsburgh sportswriters used it as early as 1922 to describe the drop of his curveball, though its origin is unclear. According to sportswriter William Peet of the Pittsburgh Post, longtime Pirates catcher Walter Schmidt was the first to refer to Morrison’s bender as a jughandle;22 the pitcher himself claimed teammate and second sacker Cotton Tierney came up with the nickname.23 By 1924, it had taken on another meaning, too: Morrison’s love of the jug’s handle. It was the time of Prohibition, but alcohol consumption was an open secret. “Johnny was not one to turn down a drink on a hot day — or a cold one, either,” wrote the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette;24 while longtime Brooklyn Eagle sportswriter Tommy Holmes wrote that Morrison’s “outstanding characteristics were a love for cawn likker sic and a command of a low curve ball.”25 Morrison was typically described as a likeable, yet competitive teammate who also possessed an “independent temperament.”26 Morrison’s behavior over the rest of his career became more erratic as he clashed with managers and teammates over his alcohol abuse, which sportswriters at the time covered up as another case of the flu or grippe.

With heightened expectations, Morrison pitched inconsistently in 1924 as the Pirates once again challenged McGraw’s machine for the pennant but came up just a few games short. Ten days after tossing eight innings in a no-decision as the Bucs Opening Day starter, Morrison was tagged a for a career-most 10 runs and permitted 20 baserunners in a distance-going 10-4 loss to the Reds on April 25. Never one to dwell on losses, Morrison hurled one of the best games in his next outing, tossing a career-most 14 innings against the Cubs. He was at bat with two outs and two strikes when Rabbit Maranville courageously stole home for the deciding run in a 2-1 win at Wrigley Field. Morrison’s record dipped to 5-11 on July 1 as the Pirates struggled to play .500 ball.

The Pirates mounted one of their famous late-season comebacks, but instead of Morrison leading the charge as in previous years, others were at the forefront. Cooper rebounded to notch 20 wins for the fourth time in five seasons; 31-year-old rookie Ray Kremer won 18; and another rookie, Emil Yde, went 16-3. Morrison was said to be 25 pounds overweight (about 190);27 and also suffering from a “strained ligament.”28 Over the last seven weeks of the season, he made only four starts, confined to long relief. He tossed 5⅔ innings of scoreless relief in the first game of a twin bill against the Cubs on September 1, emerging victorious on Kiki Cuyler’s walk-off single to push the Pirates to within a game of first place. They never came closer as the Giants’ high-powered offense, which easily led the majors with an average of 5.6 runs per game, captured their fourth straight pennant.

With his record dipping to 11-16, Morrison completed just 10 of 25 starts among his 41 appearances (tying teammate Kremer for the NL lead) and posted a staff-worst 3.75 ERA in 237⅔ innings. McKechnie’s “Big Five” (Cooper, Kremer, Lee Meadows, Morrison, Yde) combined to start 142 games, tossed 1,189 innings (85.7 percent of the team’s total), and won 78 times.

The Deacon wasn’t satisfied with yet another close call. Weeks after the season, the Pirates executed one of the blockbuster trades of the decade, sending Cooper, widely regarded the NL’s premier southpaw, and two starters, first baseman Charlie Grimm and second baseman Rabbit Maranville, a future Hall of Famer, to the Cubs in exchange for pitcher Vic Aldridge, first sacker George Grantham, and heavy-hitting prospect Al Niehaus. Pittsburgh sportswriters widely panned the trade, but McKechnie considered the heavy drinkers Grimm and Maranville bad influences on the team.

Some thought Morrison would be purged, too, in the shakeup, but he was back with the team in 1925. He vehemently denied “stories that boozing caused his poor showing” the previous year and promised to adhere to “training rules,” a euphemism for drinking.29 While the Bucs stumbled out of the gate, losing 16 of their first 30 contests, Morrison was a bright spot. By the end of May he had six victories as the Pirates had already begun clicking on all cylinders. On June 29 Morrison “whipped his curve and fast ball over the plate in a masterly fashion,” gushed Charles J. Doyle, in a complete-game win against the Reds, 8-1, at Crosley Field. It was the streaking Pirates’ 15th win in their last 18 games to move them into a first-place tie with the Giants. “The Pirates of 1925 seem to have the heart, the fight and ability to throw fear into the other fellows,” exclaimed the Pittsburgh Post about a club that had been as many as nine games back, and 7½ back on June 10. “The hitting will overcome a lot of shortcomings.”30

The Pirates supplanted the Giants as the highest-scoring offense in the majors. Seven of eight starters batted at least .308 while Kiki Cuyler emerged as one of the most dangerous all-around players in the league, scoring a major-league-high 144 runs and hitting.357. Over the last 10 weeks of the season, Morrison lost his effectiveness as a starter, failing to reach the fifth in five of his eight starts; however, he re-established his role as fireman, winning three straight decisions in relief in a four-day span in early August.

In leading the Pirates to their first pennant since 1909, McKechnie relied once again on his “Big Five,” each of whom logged 200-plus innings: Meadows (19-10), Kremer (17-8), Morrison (17-14), Yde (17-9) and Aldridge (15-7), who combined for 138 starts and logged 1,101⅓ innings, while also regularly relieving. Factor in 43-year-old Babe Adams (6-5, 10 starts, 101⅓ innings), and it was essentially a six-hurler staff that logged 88.8 percent of the team’s innings. Morrison led the league in appearances (44), completed nine of 26 starts and posted a 3.88 ERA in 211 innings.

Morrison’s eventual downfall with Pirates can be traced to the World Series pitting the Pirates against the Washington Senators. Skipper Bucky Harris’s squad took two of the first three games from the Pirates, who trotted out Meadows, Aldridge, and Kremer as starters. In a decision that drew hefty criticism and lots of second-guessing, McKechnie tabbed Yde, who had made just one start since September 13, as the Game Four starter on October 11 in the nation’s capital. He lasted just 2⅓ innings, yielding four runs, before Morrison relieved for the second time in the Series (he had tossed the final inning in the opener), holding the Senators scoreless over 4⅔ innings.

On the brink of defeat, the Pirates mounted one of the great comebacks in the history of the fall classic. They won the next two games with Aldridge and Kremer going the distance for the second time each to set up the deciding game in Pittsburgh on October 15. In another surprising decision, McKechnie bypassed Morrison, in favor of Aldridge on two days’ rest to face the era’s greatest pitcher, Walter Johnson, who had won both of his starts in the Series. In a sloppy game in the rain, Aldridge recorded just one out and was tagged for four runs. Morrison stopped the bleeding, though he himself yielded two runs in 3⅔ innings and departed with the Pirates trailing 6-3. The Bucs exploded for five runs late in the game while Kremer tossed four scoreless frames to pick up the win and Red Oldham, who had made just 11 appearances all season, tossed a scoreless ninth to secure the Pirates’ first championship since 1909. Morrison was livid with the way he was used, and never forgave the Pirates. “I really should have jumped the Pittsburgh team in that final game of the 1925 World Series,” he said in retirement. “I felt like I was the logical choice.”31

Morrison’s career was never the same after the World Series and his final two seasons with the Pirates were filled with strife and animosity. Over the first six weeks of the 1926 season, Morrison pitched well, tossed two shutouts, and pushed his record to 6-5 with a complete-game victory in the second game of a twin bill on May 31. Then it turned ugly. He didn’t accompany the team on an Eastern road swing that commenced on June 6. Pittsburgh papers cited both a bad case of the flu and an injured arm as a reason. Morrison finally took the mound again, on June 27, walking the only batter he faced.

Shelved again, supposedly to rest his injured arm, Morrison finally had enough and went AWOL, returning to his home in Kentucky. “I just got tired hanging around Pittsburgh not being able to do anything,” said Morrison. “I realize I am going to be suspended, but when my arm gets well, I will write McKechnie.”32

In late July the Pirates suspended the disgruntled hurler indefinitely. Around the same time, the Pirates were rocked by an even bigger scandal. Known as the “ABC Affair,” it was an insurrection, led by Babe Adams, Carson Bigbee, and Max Carey, all of whom resented club vice president and former skipper Fred Clarke’s presence in the dugout. The players were subsequently released on August 13. Many expected Morrison to be released, too, but unlike his three teammates, he was still thought to be productive. Morrison and the Pirates reconciled, and the pitcher was back on the mound on August 23, though he proved ineffective in limited use. The Pirates limped to a 23-24 record down the stretch to finish in third place in one of the most disappointing seasons in franchise history. It also led to the firing of McKechnie.

The Pirates were unable to unload their problem child in the offseason. From the outset, Morrison clashed with the team’s new skipper, disciplinarian Donie Bush, and was relegated to the bullpen as the season began. In early June he came down with another “cold” in the heat of summer (or was nursing a sore arm, depending on the day, sportswriter, or Smoky City newspaper) and missed two weeks, returning to action on June 17. On July 2 he yielded five hits and four runs in three innings of relief against the Reds at Forbes Field in what proved to be the last time he was in a Pirates uniform. He went AWOL again the next day.

Pittsburgh papers resurrected the sore-arm story (and in fairness to Morrison, he probably had a sore arm), but also mentioned the flu, and an even wilder tale, namely that Morrison had fallen down a flight of stairs and seriously bruised and cut his hand. One can only wonder if that story held at least a kernel of truth. In any case, it was later revealed that Morrison had once again jumped the team and had gone back to Owensboro. “I never was a bullpen pitcher,” said Morrison defiantly years later. “I was a mound pitcher.”33

The Pirates suspended Morrison indefinitely on July 14. Bush “looks upon Morrison’s indifference as a challenge to his authority,” pronounced Wollen, justifying the punitive measure.34 Commissioner Kenesaw Landis subsequently placed Morrison on the ineligible list.

Pittsburgh sportswriters were quick to praise Morrison’s contributions to the team’s success during a productive five-year-run (1921-1925) but were fatigued by his shenanigans. “Jughandle Johnny has always been his worst enemy in baseball,” opined scribe Ralph Davis in the Press. “He possessed plenty of ‘stuff’ to make himself a real big winner, but he cared less for the welfare of his team than he did for the sip that leads to the sip that inebriates.”35 Without Morrison, the Pirates held off challenges by the Cardinals and Giants to capture their second pennant in three years. They faced Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and the Bronx Bombing New York Yankees in the World Series and were swept in four games.

The Pirates’ divorce from Morrison was not as easy, or as quick, as they had hoped. First, he had to be reinstated by Landis before they could execute a trade or sale, and that did not happen until the following spring. After Morrison passed through all 15 teams on waivers, the Pirates sold him to Montreal in the International League at the end of March.36 Morrison, who was still in Owensboro and did not participate in spring training, refused to report to Montreal and the deal was nullified. He was subsequently released outright and sold to the Kansas City Blues in the American Association in mid-April.

Morrison labored through a lackluster partial season with the Blues, going 1-6 and logging 95 innings, mainly in relief. He returned to the club in 1929 and made six more appearances.

Morrison had burned bridges, fought with his superiors, and jumped the Pirates twice, but he was still the Jughandle, and big-league managers were in love with his curveball. If sport is about second chances, then Morrison was the poster child. On June 5, 1929, the Brooklyn Eagle reported that the lowly Robins, who had finished in sixth place five of the last six seasons (save for a surprise second-place showing in 1924), had purchased the 33-year-old curveballer for a 30-day trial.37

Without hyperbole, Morrison enjoyed one of the best 30-day stretches in his baseball life. Excluding his debut on June 7, when he was whacked for six hits and four runs in 4⅔ innings of relief, Morrison yielded just two runs in his next 23⅓ innings (covering eight relief appearances), won four contests, and was awarded retroactive saves in four games (the save did not become an official statistic until 1969) from June 10 to June 25. He was promoted to the starting rotation, tossed complete games in his first two starts to push his record to 6-0. Morrison didn’t provide the Robins a fairy-tale season (they finished sixth again), but he had the last laugh, going 13-7 for a team that lost 88 games, appearing in 39 games, including 10 starts, and logging 136⅔ innings with a 4.48 ERA, which when adjusted for ballpark factors was a tad better than league average.

Morrison’s honeymoon with the Robins and their namesake, skipper Wilbert Robinson, lasted only one season. Pitching exclusively out of the bullpen, Morrison made 16 mostly ineffective appearances (5.45 ERA in 34⅔ innings) when he “went fishing” after tossing two scoreless innings against the Reds at Crosley Field on June 19.38 That was Jughandle’s euphemism for jumping the team and heading back home to Kentucky. The Robins suspended him indefinitely the next day and subsequently released him unconditionally.

Despite his reputation, Morrison wasn’t quite finished with professional baseball. In 1931 he was back in the league where he first garnered attention, signing with the Atlanta Crackers in the Southern Association. His record wasn’t pretty (7-14), but the 35-year-old logged 222 innings with a robust 3.77 ERA. The next season, he lasted less than three months before he “went fishing” again. He was suspended indefinitely in mid-June, bringing his career in O.B. to a close.

Morrison had no intention of hanging up his spikes yet. He pitched for independent teams in Owensboro for the next few years. He claimed he tore ligaments and ruined his arm in 1934, though even those injuries healed enough for him to keep tossing the ball.

In parts of 10 seasons in the big leagues, Jughandle went 103-80, completed 89 of 164 starts among his 297 games, and logged 1,535 innings with a 3.65 ERA.

Morrison lived in Owensboro most of his life. In February 1920, he married a local resident, Mary Alberta Fister, and together they had at least three children, John Jr., Robert, and Dwane, who became a successful college basketball coach, notably with Georgia Tech (1973-1981). According to the 1940 US Census, Morrison, then 45 years old, was unemployed, while his wife worked as a bottler in a local distillery.

Morrison suffered from a number of illnesses later in life, including diabetes, and also lost both of his legs, presumably to the disease.39 On March 20, 1966, he died at the VA Hospital in Louisville at the age of 70. His death certificate listed uremia (kidney failure) as the cause. He was buried at Rosehill cemetery in Owensboro.

Acknowledgments

This biography was edited by Len Levin and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Morrison’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com, The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record, SABR.org, extensive use of the archives of the Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh Post, Pittsburgh Gazette Times, and Brooklyn Eagle, and Ancestry.com

Notes

1 Thomas Holmes, “Robins Hope Johnny Morrison, Only 31 Years Old, Can Come Back,” Brooklyn Eagle, June 16, 1929: 6C.

2 James Pendleton, “Played Back-Yard Ball In Owensboro. Now Star Catcher of Pittsburgh Club,” (Louisville) Courier-Journal, March 18, 1923: section 6, 5.

3 I’d like to thank SABR member Ed Washuta for invaluable assistance and research exploring Morrison’s professional baseball career from 1915-1917. The 1924 edition of Who’s Who in Baseball shows that Morrison played for Anniston in 1915-1917; those records for Morrison were repeated in many subsequent publications, including The Sporting News. However, upon closer examination, this appears to be an error as ample proof exists that Johnny Morrison did not play for Anniston. Washuta demonstrated unequivocally that the reserve list for Anniston for 1915 (The Sporting News, October 21, 1915) lists a player named Harry Morrison. In 1916, NAPBL Bulletin #11 (May 10, 1916) lists a Jim Morrison with a contract from Anniston, and Jim Morrison also appears in the Anniston reserve list that fall (The Sporting News, November 2, 1916). This may have been the same player identified previously as “Harry.” Furthermore, newspaper clippings from the (Nashville) Tennessean, Atlanta Constitution, and Anniston (Alabama) Star from 1915-1917 mention a Harry or Jim Morrison.

4 Pendleton.

5 “Corsairs Buy Dixie League Hurling Star,” Pittsburgh Post, August 19, 1920: 8

6 L.H. Wollen, “Reds Cinch Third Place,” Pittsburgh Press, October 3, 1920: 19.

7 “Pirates Notes,” Pittsburgh Post, June 9, 1921: 9.

8 “Pirates Oppose Bruins,” Pittsburgh Press, June 27, 1922: 18.

9 Charles J. Doyle, “Chilly Sauce,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, July 7, 1921: 19.

10 Edward F. Balinger, “Bucs End Slump and Beat Robins, 2-0,” Pittsburgh Post, August 29, 1921: 8.

11 Charles J. Doyle, “Chilly Sauce,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 12, 1922: 21.

12 Jack Ryder, “Nine Ciphers Are Rule for Reds,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 18, 1922: 10.

13 Charles J. Doyle, “Bucs Blank Reds for Season’s Second Win,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, April 18, 1922: 10.

14 Charles J. Doyle, “Pirates Win First Game in East, 5-0,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, June 8, 1922: 9.

15 Robert W. Maxwell,” John Morrison Uses Roundhouse Hook and Foils Phillies,” Evening Public Ledger (Philadelphia), June 8, 1922: 22.

16 Edward P. Balinger “Morrison Twirls Great Ball and Pirates Beat Giants,” Pittsburgh Post, “July 31, 1922: 6.

17 Edward F. Balinger, “Pirates Win in Ninth, 2-1 And Seize Third Straight From Bears,” Pittsburgh Post, April 28, 1923: 11.

18 Edward F. Balinger, “Pirates Put Punch in Flag Race, Beating Giants as Reds Take Two,” Pittsburgh Post, August 21, 1923: 11.

19 Edward J. Balinger, “Morrison’s Curves Prove Mysterious to Moran’s Tribe,” Pittsburgh Post, September 4, 1923: 9.

20 L.H. Wollen, “Pirates Shut Out Chicago,” Pittsburgh Press, September 9, 1923: 21.

21 Charles J. Doyle, “Pirates Close Home Season With Victory,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, September 27, 1923: 11.

22 William Peet,” What the Post Clock Saw,” Pittsburgh Post, September 19, 1923: 11.

23 Bruce Dudley, “Bruce Dudley’s Whatnot,” Louisville Courier-Journal, June 13, 1937: 57.

24 “The benchwarmer. The Language of Baseball,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 5, 1936: 15.

25 Tommy Holmes, “Double Bill Gives Flock Two Shots at Philly Jinx,” Brooklyn Eagle, August 10, 1939: 15.

26 Edward F. Balinger, “Buccaneers Spend Idle Day in Philly as Bush Forbids Seashore Trip,” Pittsburgh Post, July 18, 1927: 9.

27 Edward P. Balinger, “Buccaneers Suddenly Come Back to Life and Crush Reds, 9-4,” Pittsburgh Post, June 21, 1924: 10.

28 Charles J. Doyle, “Chilly Sauce,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times,” August 9, 1924: 9.

29 Lou Wollen, “Johnny Morrison Expects to Have a Big Year,” Pittsburgh Press, March 22, 1925: 18.

30 “From Mile in Rear to Mile in Front, Cellar Champs of Late April Crash Through to Show Heels to Giants,” Pittsburgh Post, June 30, 1925: 11.

31 Dudley.

32 Lou Wollen, “Johnny Morrison Draws Suspension,” Pittsburgh Press, July 24, 1924: 11.

33 Dudley.

34 Lou Wollen, “Bush Angered by Johnny’s Actions,” Pittsburgh Press, July 15, 1927: 30.

35 Ralph Davis, “Ralph Davis Says,” Pittsburgh Press, March 28, 1927: 27.

36 Lou Wollen, “Pirates Sell Johnny Morrison to Montreal Club,” Pittsburgh Press, March 31, 1928: 12.

37 Tommy Holmes, “Robins Recover Vance and Buy Johnny Morrison From Kansas City,” Brooklyn Eagle, June 5, 1929: 28.

38 Dudley.

39 Earl Ruby, “Ruby’s Report,” (Louisville) Courier-Journal, December 31, 1964: 19.

Full Name

John Dewey Morrison

Born

October 22, 1895 at Pellville, KY (USA)

Died

March 20, 1966 at Louisville, KY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.