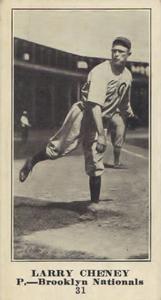

Larry Cheney

Over a three-year span, 1912 to 1914, Larry Cheney was one of the National League’s most durable and effective pitchers, racking up more than 300 innings each season and joining Joe McGinnity, Deacon Phillippe, Vean Gregg, and Wes Ferrell as the only hurlers ever to reach the 20-win mark in each of their first three full seasons. The 6’1″, 190 lb. spitballer was also one of the wildest pitchers in history. His 26 wild pitches in 1914, double that of any other NL hurler, remain a Chicago Cubs record to this day, and his 72 wild pitches in just short of four complete seasons in a Bruins uniform are still the team’s all-time career record. In 1915, despite pitching only half the innings of his three previous seasons, Cheney fell short by only one errant toss of leading the NL in wild pitches a record seven consecutive years. Still, Cheney managed to lead the league in six of his eight seasons, a record he shares with Nolan Ryan and Jack Morris, and his five wild pitches in one game in 1918 was the record until 1979.

Over a three-year span, 1912 to 1914, Larry Cheney was one of the National League’s most durable and effective pitchers, racking up more than 300 innings each season and joining Joe McGinnity, Deacon Phillippe, Vean Gregg, and Wes Ferrell as the only hurlers ever to reach the 20-win mark in each of their first three full seasons. The 6’1″, 190 lb. spitballer was also one of the wildest pitchers in history. His 26 wild pitches in 1914, double that of any other NL hurler, remain a Chicago Cubs record to this day, and his 72 wild pitches in just short of four complete seasons in a Bruins uniform are still the team’s all-time career record. In 1915, despite pitching only half the innings of his three previous seasons, Cheney fell short by only one errant toss of leading the NL in wild pitches a record seven consecutive years. Still, Cheney managed to lead the league in six of his eight seasons, a record he shares with Nolan Ryan and Jack Morris, and his five wild pitches in one game in 1918 was the record until 1979.

Born in Belleville, Kansas, on May 2, 1886, Laurance Russell Cheney came out of his hometown as a catcher, perhaps explaining his future wildness. When Larry reported to Topeka of the old Western Association in 1906, manager Dick Cooley took one look at the 20-year-old’s rocket arm and turned him into a pitcher. The transformation wasn’t smooth. “I was as wild as a hawk and managers wouldn’t have anything to do with me,” Cheney admitted in a 1941 interview with The Sporting News. Following a two-year stint with Bartlesville, Oklahoma, he was sold to the Chicago White Sox for $1,000. Though Cheney never pitched an official game for the Pale Hose, it was during his brief stint with the team in the spring of 1907 that he learned his money pitch from Big Ed Walsh, arguably the greatest spitball pitcher of all-time. The ChiSox had no patience to wait for Larry to develop his spitter, however, and returned him to the bushes of Bartlesville.

After spending 1908 with Indianapolis of the American Association, Cheney signed with the Cincinnati Reds in 1909. Manager Clark Griffith, himself a former pitcher, wasn’t a fan of spitballers, and the Reds shipped the Kansas cyclone back to Indianapolis. Injuries and illness plagued Larry’s tenure with the Hoosiers. While in spring training with Cincinnati in 1911 he contracted walking typhoid. It was back to the minors once again after the Reds’ physician looked him over, but this time Larry opened eyes by winning 19 games for a Louisville team that finished deep in the American Association’s basement.

Purchased by the Chicago Cubs late in the 1911 season, Cheney made a “smash” in his first major league start. He’d struck out 10 Brooklyn Superbas and hadn’t yielded a single run through 7⅔ innings when a screaming liner off the bat of Zack Wheat forever changed his pitching style. “I just had time to throw up my hand to save my face, perhaps my life,” Cheney recalled. “The ball broke the little finger on my right hand and jammed my thumb so hard against my nose, it broke my nose, too. The next year my thumb was so weak I couldn’t grip the ball with it, so I developed an overhand delivery.” His newfound delivery caused his spitball to shoot up, making it more effective. Cheney’s rookie season of 1912 proved the best of his nine-year major league career. His 26 wins tied Rube Marquard for the NL lead, while his 28 complete games topped all pitchers.

In his sophomore season, 1913, Cheney led all major league pitchers in appearances (54) and saves (11). A four-game series with Cincinnati shows how Johnny Evers, the Cubs new manager, used him. Cheney appeared in all four games, pitching a complete-game win in game one and picking up saves in games two and three. In the final game, he gave up a two-run homer to Johnny Bates in the eighth inning, tying the game at 5-5, but was still on the mound when the game was called in the 11th inning to permit the Cubs to catch a train to St. Louis. Cheney believed he would get the next day off, but when the Cardinals knocked Jimmy Lavender out of the box in the seventh inning, Evers called on his workhorse yet again. The game dragged on for 17 innings, with Cheney pitching until the end. After that, Evers gave Larry two weeks off to rest his weary arm.

The Cubs ace began the 1914 season inauspiciously, walking eight, hitting two batsmen, and uncorking four wild pitches, an Opening Day record that still stands. He quickly regained his old form, however, pitching six shutouts and a pair of one-hitters among his 20 victories. Again he led the majors in games pitched with 50. But in 1915, after three sensational seasons on the mound, Cheney’s career took a turn for the downside. He began the year just as he had in 1914—wild. New Cubs manager Roger Bresnahan had little patience for pitchers who failed to find the plate, often yanking them at the first minor sign of wildness. Cheney quickly went from one of baseball’s most durable pitchers to one who was yanked in 12 of his first 20 starts, the most incomplete games in the NL to that point of the 1914 season. It was rumored as early as May that all was not harmonious between Bresnahan and his ace. Trade rumors began to fly.

On August 31, 1915, the Cubs sent Cheney to the Brooklyn Robins. Wilbert Robinson thus became Larry’s fifth manager in as many seasons, four of whom (Frank Chance, Evers, Bresnahan, and Robinson) ultimately were enshrined in the Baseball Hall of Fame. That same day Brooklyn also signed Rube Marquard, and the two acquisitions paid off the following year. Coming off a mediocre 8-11 record, the 30-year-old Cheney put together one last outstanding season in 1916, winning 18 games to help Brooklyn to its first pennant since 1900. He struck out a career-high 166 batters, just one behind NL leader Pete Alexander, and topped all NL twirlers in lowest batting average allowed. During the World Series, however, Uncle Robbie used Cheney only as mop-up, and the spitballer pitched just three innings as Brooklyn dropped the Series to the Boston Red Sox.

Larry Cheney never again equaled his exploits of previous years, though he did show occasional flashes of brilliance. In late June of 1917, for example, he tossed a beauty against the Phillies, allowing only six hits in a 1-0 loss. Cheney continued his hot streak into July, winning four in a row and not allowing an earned run over the course of 27 innings. That August he pitched 13 innings of shutout ball, all in relief, yet didn’t earn the win in Brooklyn’s 22-inning, 6-5 victory over the Pirates, at the time the longest game in major league history. During that marathon Cheney figured in one of those “believe it or not” oddities of the Deadball Era: By striking out in the 18th inning, he was the only Brooklyn batter to fan in the entire contest. After falling all the way from first to seventh in 1917, Brooklyn opened the 1918 season by dropping nine games in a row before Cheney snapped the skid by defeating the Giants. He went 11-13 that season before exiting the majors following a 3-10 mark in 1919.

After bouncing around the minors for three years, including a two-year stint in the Sally League in which he compiled a 42-11 record, Larry Cheney gave up baseball and devoted all of his time to operating an orange grove. He became bitter over the ensuing years when his aspirations to return to the game as a coach or scout never were fulfilled. Sometime in the 1960s, the old warrior completed a questionnaire sent to him by the Baseball Hall of Fame. Battling a case of pulmonary emphysema, Cheney wrote that he was retired and unable to work. The final entry on the questionnaire asked: “If you had to do it all over again, would you play professional baseball?” Cheney responded: “No.” He died in Daytona Beach, Florida, on January 6, 1969.

Note: A slightly different version of this biography appeared in Tom Simon, ed., Deadball Stars of the National League (Washington, D.C.: Brassey’s, Inc., 2004).

Sources

For this biography, the author used a number of contemporary sources, especially those found in the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library. He also made use of The Sporting News and the Chicago Tribune.

Full Name

Laurence Russell Cheney

Born

May 2, 1886 at Belleville, KS (USA)

Died

January 6, 1969 at Daytona Beach, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.