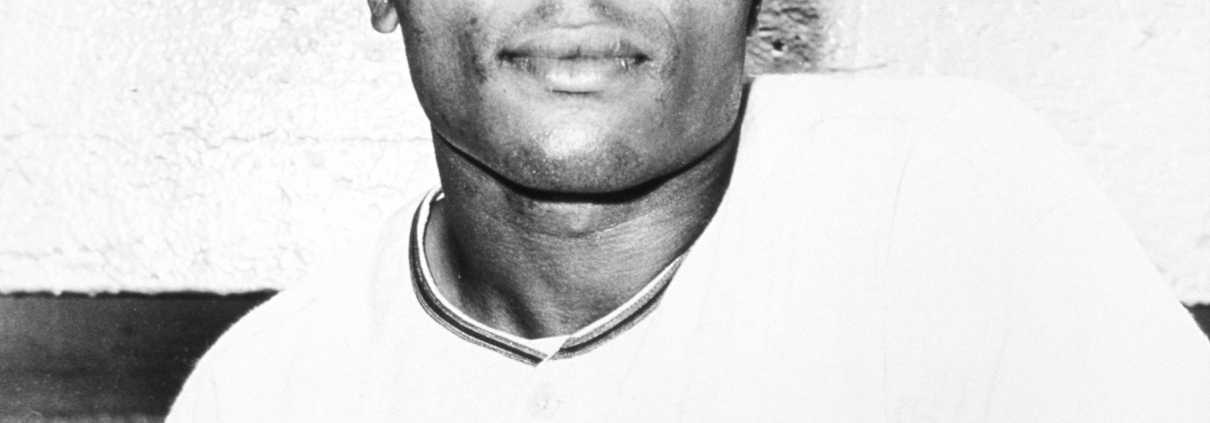

Leon Wagner

Maybe it was Leon Wagner’s bad luck to have been born too soon. A major-league outfielder for 12 years, Wagner was a two-time All-Star who averaged 29 home runs and 87 RBIs from 1961 through 1966. Still, because of fielding deficiencies that were either imagined (his opinion) or real (his managers’ views), he always seemed to be fighting for playing time. His final season in the majors was 1969, just four years before the advent of the designated hitter, a spot that would seem to have been a perfect fit for him.

Maybe it was Leon Wagner’s bad luck to have been born too soon. A major-league outfielder for 12 years, Wagner was a two-time All-Star who averaged 29 home runs and 87 RBIs from 1961 through 1966. Still, because of fielding deficiencies that were either imagined (his opinion) or real (his managers’ views), he always seemed to be fighting for playing time. His final season in the majors was 1969, just four years before the advent of the designated hitter, a spot that would seem to have been a perfect fit for him.

Leon Lamar Wagner was born on May 13, 1934, in Chattanooga, Tennessee. He and his parents, Eugene and Hattie Lee Wagner, moved to the Detroit area when Leon was an infant, when his father was hired by a foundry. In 1952 Wagner graduated from Inkster High School — Inkster is now a town of 30,000 about 20 miles west of Detroit. He was a three-sport athlete for Inkster’s Vikings, starring in baseball, basketball, and football. Wagner next enrolled at Tuskegee University — then known as Tuskegee Institute — in Alabama, on a football scholarship. He was there for three semesters before returning to Michigan, where he found a job in the auto industry.

Before the 1954 season, New York Giants scout Ray Lucas signed Wagner, who was playing for a sandlot team called the Inkster Panthers. Wagner was sent to the Danville (Illinois) Dans of the Class-D Mississippi-Ohio Valley League that spring. He played in 125 games for Danville and led the league with 160 hits. He had 24 home runs and 115 RBIs, that latter figure still a Danville team record, and hit .332. In a sign of things to come, Wagner also led the league’s outfielders with 14 errors.

The offensive numbers persuaded the Giants to move Wagner up a step to the Class-C Northern League in 1955.Playing for the St. Cloud (Minnesota) Rox, he led the league with 29 home runs and 127 RBIs and hit .313. Once again, he committed 14 errors in the outfield. The next year with Danville (Virginia) of the Carolina League, he batted .330 and led the league with 51 homers and 166 RBIs. With Danville he played with three other future major-league stars — shortstop Jose Pagan, third baseman Tony Taylor, and first baseman Willie McCovey.

After the 1956 season Wagner was drafted into the US Army, with whom he spent 14 months at Fort Carson, Colorado, driving a Jeep. After the year off from baseball, the Giants advanced him to Phoenix in 1958 to join their new Pacific Coast League team. The New York Giants had moved to San Francisco, and their top farm club was now in Phoenix. Wagner’s stay was brief. After 65 games in the PCL, in which he hit .318 with 17 home runs and 58 RBIs, he was recalled by the Giants and made his big-league debut on June 22, 1958.

Taking over left field, Wagner appeared in 74 games and hit 13 home runs in his rookie year with 35 RBIs and a .317 average. Garry Schumacher, a Giants public-relations executive, told San Francisco Examiner sports editor Curley Grieve shortly after Wagner was called up that Wagner reminded him of a “left-handed Hank Aaron” the way “he crushes that ball.”1 Jack Schwarz, a Giants farm system executive, recalled that Wagner had not been impressive when signed and was about to be released, but pleaded for another chance. “Anybody who loves baseball that much deserves another chance,” Schwarz told reporters.2

Even early in his big-league career, Wagner faced questions about his outfield play. Grieve, in an August 23, 1958, column, wrote: “Unfortunately, Wagner can’t field like he can hit,” but he quoted Wagner as claiming that he was “not a bad outfielder.”3

That was as close as Wagner would ever get to full-time status in San Francisco. Manager Bill Rigney had expressed reservations about his defense, telling a writer from Newsday years later that Wagner “didn’t even care about fielding” when he was with the Giants.4 Wagner made five errors in that first half-season, and Rigney opted to use Jackie Brandt in left field for most of the 1959 season. Brandt appeared in 137 games while Wagner was in 87, recording only 5 home runs and 22 RBIs while his average slumped to .225. It was the first time at any level that Wagner had ever failed to hit .300. On December 15, 1959, the Giants traded Wagner and third baseman Daryl Spencer to the St. Louis Cardinals for second baseman Don Blasingame. Within days, some Bay Area writers speculated that the team had given up too much for the light-hitting Blasingame, a defensive specialist.5

Wagner said after the trade that he “was never given any encouragement in San Francisco,” and that Rigney and coach Salty Parker “would give me the hard look” if he misplayed a ball in the outfield.6 He denied being a poor outfielder but acknowledged that alongside Willie Mays, Brandt, and Felipe Alou, “I had to look bad by comparison.”7

Wagner had few opportunities to play regularly for the 1960 Cardinals, who had Stan Musial, Curt Flood, and Joe Cunningham as regulars. He spent extra time during spring training working on his defense with manager Solly Hemus and coach Harry Walker. Shortly before the season began, Hemus said Wagner was “at least average” defensively, and Walker — who had Wagner chasing fly balls hit to him by a modified pitching machine — said Wagner’s ability to track fly balls and his throwing had improved.8

What didn’t improve was his hitting. Playing sparingly and often only as a pinch-hitter, Wagner appeared in only 39 games for the Cardinals with 4 home runs and 11 RBIs. One of those home runs may have meant a bit more to him than the others. On April 12, in his first time back in San Francisco since being traded, Wagner hit the first-ever home run at Candlestick Park, the Giants’ brand-new stadium. Wagner was hitting .214 on June 15 when the Cardinals optioned him to Rochester. Things improved somewhat in the International League, where he hit 16 home runs and drove in 48 in 93 games, but his .265 average marked the first time he had been under .300 in the minors.

While Wagner was too early to take advantage of the DH, he was just in time for baseball’s expansion. The American League had operated with eight teams since it was established in 1901, but two new clubs — the Los Angeles Angels and Washington Senators — had been created and would begin play in 1961.

Wagner was traded to the Angels in mid-April and almost immediately became a star. Playing as a regular for the first time at age 27, Wagner led the expansion club with 28 home runs, while his 79 RBIs were second on the team. He hit .280 and even led the team’s outfielders with 12 assists. Wagner was reunited with manager Bill Rigney, who had held the same post in San Francisco. The day he was acquired, Rigney told the Associated Press, “I like the way he swings the bat.”9

In 1962, his second season in Los Angeles, the approachable Wagner became a favorite with sportswriters. He got off to a great start that year, hitting nine home runs in the team’s first 18 games. He told Los Angeles Times writer Braven Dyer in early May that “I’m playing baseball with everything I have and that’s the only way I know how to play it.”10

The same writer asked Rigney how good he thought Wagner could be. “He can be one of the very best,” Rigney said, “and he can hit 40 or so home runs. If he keeps away from bad pitches, he will become one of the American League’s outstanding hitters.”11Rigney was right. Wagner enjoyed the best year of his career in 1962, setting personal records for home runs (37), RBIs (107), doubles (21), triples (5), and base hits (164). He hit .268, and finished fourth in the MVP voting.

From 1959 through 1962, there were two All-Star Games each year. Wagner was MVP of the second 1962 game, at Chicago’s Wrigley Field, with a two-run homer, two singles, and a key catch in the AL’s 9-4 win. Of his catch, which took an extra-base hit away from George Altman, Wagner told writers: “A man don’t have to be a bad fielder all his life. It isn’t that hard to catch baseballs.”12 He called the All-Star Game performance “the biggest thrill of my life.”13 In large part as a result of Wagner’s great year, the Angels finished third with an 86-76 record in only their second year of existence.

Wagner had another great start in 1963, contending for the league lead in home runs, batting, and RBIs until mid-July. He then cooled off, finishing at .291 with 26 home runs and 90 RBIs, but earned another All-Star Team selection.

Surprisingly, Wagner was traded to Cleveland on December 2, 1963, for pitcher Barry Latman and first baseman Joe Adcock. A few weeks later, Wagner was asked for his feelings about the trade. His response: “I don’t see how anybody could be happy over leaving the Angels. I’m going to miss the players. I’ll miss [Rigney] more than anything. He’s the man who brought me back from the minors and I’ll never forget it. … I’m trying to take the trade the way a ballplayer should. It’s business.”14 One Los Angeles columnist wrote, “It is difficult to see how the trade can help Los Angeles.”15

The deal turned out to be as one-sided as it had seemed it might be. Latman was 6-10 as a part-time starter and reliever in 1964, while Adcock hit 21 home runs for the Angels, but with only 64 RBIs. Wagner, on the other hand, enjoyed one of his best seasons in his first year in Cleveland. Playing in 163 games, he hit 31 home runs, drove in 100 runs, and even stole 14 bases, displaying a side of his game not seen before.

Wagner became as popular with Cleveland writers as he had been with those in Los Angeles. He never ducked the press and frequently had a humorous response for the mundane questions ballplayers often face. He often referred to himself as Daddy Wags. One columnist called him the Good Humor Man, after the popular brand of ice cream that was sold door-to-door from a truck. Another, writing of Wagner’s easygoing attitude, quoted him as saying, “I don’t dig people who put baseball in the same class with going to church. I don’t kick water coolers or throw (batting) helmets. Maybe if other players watch me, they’ll take a lesson from me and not be so grouchy.”16

Wagner told another writer that when he was hitting well in 1964 and former teammate Mays was going through a slump in San Francisco, he called Mays and told him, “How’d you do today, Willie? Oh, not so good, huh? That’s too bad. By the way, I hit another one today. It don’t look so hot when a little old $30,000 ballplayer like me starts leaving $100,000 men in the dust.”17 Mays hit 47 home runs that year to Wagner’s 31. Cleveland teammate Bob Chance said of Wagner, “Daddy Wags is a good storyteller. It’s not that Daddy Wags don’t tell the truth. It’s just he embroiders it.”18

Wagner apparently was a good fit with fans, as well. Cleveland Press reporter Regis McAuley wrote in June 1964, “On the public relations side of things, Daddy Wags is batting and fielding 1.000. He is in demand for speeches and appearances and he fractures his audiences. He is also very generous with his autographs, which makes him an idol of the kids who hang around the park.”19

Wagner had another solid year in 1965, smacking 28 home runs, driving home 79 runs, and batting a career-high .294. After a game-winning July home run off Baltimore’s Milt Pappas, he joked that he knew Pappas would throw him a fastball “because I was concentrating.”20 Pappas had retired him on similar pitches in the fourth and sixth innings and so when he came to bat in the eighth inning of a 2-2 game with Rocky Colavito on first base, he expected another fastball “because I’m a thinkin’ ballplayer. It was my turn to hit one.”21

Wagner was given to predicting great things for himself, most often in jest. He denied having said he would hit 65 home runs but then added, “I guess I am capable. If Roger Maris hit 61, I can hit 70.” Still, when he signed his contract for 1966, he told reporters, “One of these years — this might be the one — I’m gonna hit 55 to 60 home runs.”22

But 1966 turned out to be a year of mixed results for Wagner. His 23 home runs were his fewest as a starter, as were his 66 RBIs. He did hit a respectable .279 after lifting his average 25 points after the All-Star Game, and credited being in the lineup every day for the resurgence. “When I go to bed at night,” he told sportswriter Russell Schneider, “I know I’ll be in the game the next day. Before I go to sleep, I think about the pitcher I’ll be facing. I concentrate on what he threw me last time, what kind of pitches he uses in this situation or that one, and things like that. When you don’t know if you’re playing the next day, you think — and worry — about other things.”23

Shortly before spring training in 1967, Wagner revealed a serious side to his personality. He said he had spoken with Indians general manager Gabe Paul about a future in baseball after his playing career ended. “Mr. Paul has led me to believe that I might be the first (African-American) to get a good job in baseball when my playing days are through. Of course, that’s a long way off, but I kinda think I could get a good scouting job … a responsible job, you know … one that has administrative duties.”24

Wagner’s numbers dropped again in 1967. Now 33, he had just 15 home runs and 54 RBIs while platooning with Colavito. Still, he went to spring training with the Indians in 1968 predicting he’d hit 40 home runs “if they’ll let me play every day.”25 Alvin Dark, the new manager, reportedly had little confidence in Wagner’s defensive skills, and played him sparingly at the start of the season.26 On June 13, he was traded to the Chicago White Sox for Russ Snyder.

As Wagner’s playing time diminished, he became a successful pinch-hitter, leading the league in 1968 with 46 appearances. But he only had 211 at-bats for the season and managed just one home run and 24 RBIs to go with an average of .261. He continued to fight platooning, telling the Chicago Sun-Times’ Jerome Holtzman, “I don’t need to be platooned. Against one or two of the tough left-handers, a right-handed hitter might have a better chance, but that doesn’t always work. If I had played every day since I came up in 1958, I’d have 400 homers.”27

Wagner’s playing career was nearly at an end. After spending spring training in 1969 with the Cincinnati Reds, he was eventually signed to a minor-league contract by the Giants, who assigned him to Phoenix in May. He got into 78 games, hitting 6 home runs, driving in 41 runs, and batting .295. In June, he said he was pleased to be back in the minor leagues, free from pressure.28 He hinted that he was considering an offer to play in Japan, but nothing came of it.

Teammates voted Wagner the club’s Most Inspirational Player. He got a late-season call from the Giants, appeared in 11 games and had 4 hits in 12 at-bats. He played his final game in the major leagues on October 2, 1969. He was released six days later. Wagner returned to Phoenix for 45 games in 1970 but hit only .189.

Wagner gave baseball one last try in 1971, signing with the Pacific Coast League’s Hawaii Islanders as a coach and player. He was a full-time coach for a month, but hit a two-run home run in his first at-bat in more than a month. He also was married in Honolulu that year. In 75 games, Wagner had 9 home runs, 33 RBIs, and a .252 average. The San Diego Padres’ farm team had several other former major-league players, including Clete Boyer, Lee Maye, and George Brunet.

In those pre-free-agency days, most players had to work winter jobs to augment their baseball salaries. While with the Angels, Wagner was partner in a men’s clothing store that used the slogan “Buy your rags from Daddy Wags.” He also was a partner in a record store and worked briefly as a Los Angeles County youth counselor.

Wagner’s post-baseball life was nothing like what he had envisioned after that conversation with Gabe Paul back in 1967. He tried acting, appearing in John Cassavetes’ 1974 film A Woman Under the Influence, and as a member of a 1930s barnstorming team in The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings, two years later.

He sold cars for three years in Honolulu after his playing career ended and held a similar job after moving to Los Angeles. He did public-relations work for a Los Angeles-area racetrack. He and his wife were in the news briefly early in 1972 when he was beaten and she received minor gunshot wounds when gunmen confronted them near the Wagners’ Los Angeles apartment in an apparent robbery.

But mostly, Wagner disappeared from view until he was found dead on January 3, 2004, inside a converted closet behind a Los Angeles video store. He was 69. Friends told Los Angeles Times columnist Bill Plaschke he had been using drugs for years and had never forgiven the Angels for trading him. “I don’t think he ever got over being traded,” Mudcat Grant, a teammate in Cleveland, said.29

Lou Johnson, an outfielder for whom Wagner was traded when he joined the Angels in 1961, and a member of the board of directors of the Baseball Assistance Team, a group that helps former players in need, analyzed Wagner’s death in a conversation with Plaschke this way: “Remember the first time they sent astronauts into space, and they weren’t afraid until they landed in the ocean? That’s what happens to some old ballplayers, particularly from our era, particularly African American. When we retire, it’s like landing in the middle of the ocean without a rowboat.”30

Johnson said that Wagner’s son, Leon Jr., and daughter, Lei Juana Wagner, repeatedly tried to help their father in his later years but were rebuffed. Wagner was married to Sherry Stewart in 1959, to Doris Jean Hudson in 1965, and to Phyllis Crawford in 1971. All three marriages ended in divorce.

Cleveland columnist Bob Dolgan remembered two of Wagner’s quips in a story a few days after the outfielder’s death. “When a … writer saw him in the whirlpool and asked, ‘Is your arm sore?’ Wagner replied, ‘No. There’s nothing wrong with my arm. It’s the elbow.’ And a magazine quoted him as saying he caught the ball with one hand because “when you use two hands, the other one just gets in the way.”31

Hal Lebovitz, who covered baseball in Cleveland for more than 60 years, remembered Wagner in a column a few days after his death in this way: “Leon Wagner was one of the most pleasant, friendliest players I ever knew. Always had that incandescent smile. Yet he appears to have died … without friends or family to claim his body. … I can shut my eyes and still see his smile. But what happened along the way that caused him to leave alone?”32

Photo credit

Leon Wagner, SABR-Rucker Archive.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted numerous other sources including:

Daniel, Dan. “Do Giants Rue Trade of Spencer to Cards?” New York World Telegram, March 31, 1964.

Dolgan, Bob. “A Perfect Blend of Homers and Humor,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 9, 2004.

Dyer, Braven. “Cheerful Cheeky — He’s Bad Joke to Chuckers,” Los Angeles Times, April 6, 1963.

Dyer, Braven. “Wagner’s Wails Rankle Angels, Bring Hot Reply,” Los Angeles Times, March 21, 1964.

Jacobson, Steve. “Leon’s New Image: Leather Craftsman,” Newsday, July 31, 1962.

Lustig, Dennis. “Whatever Happened to Leon Wagner,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, exact date unknown, 1980.

“Wagner Is Real Good Hitter,” San Francisco Examiner, July 13, 1958.

United Press International, April 1, 1969.

Notes

1 Curley Grieve, “Giants’ Top Brass Tabs Wagner One of Coming Greats in Batting,” San Francisco Examiner, August 23, 1958.

2 Curley Grieve, “Despite Slump, Mays Still Greater Than Anyone Else; Does Everything,” San Francisco Examiner, July 13, 1958: 10.

3 Grieve, “Giants’ Top Brass Tabs Wagner One of Coming Greats in Batting.”

4 Joe Donnelly, “Players in the Corner,” Newsday, August 11, 1964.

5 Dan Daniel, “Do Giants Rue Trade of Spencer to Cards?” March 31, 1960. Unidentified publication in Wagner’s Hall of Fame file.

6 Stan Isaacs, “Life With the Giants Too ‘Salty’ for Leon,” Newsday, March 15, 1960, in Wagner’s Hall of Fame file.

7 Isaacs, “Life With the Giants Too ‘Salty’ for Leon.”

8 Isaacs, “Life With the Giants Too ‘Salty’ for Leon.”

9 Associated Press, “Wagner, ex-Card, to Angels,” April 14, 1961.

10 Braven Dyer, “Angels’ Wagner Believes He’s Capable of 61 homers,” Los Angeles Times, May 6, 1962.

11 Dyer, “Angels’ Wagner Believes He’s Capable of 61 homers.”

12 Dan Daniel, “All-Star Win First Since ’59,” New York World Telegram, July 31, 1962.

13 Daniel, “All-Star Win First Since ’59.”

14 Braven Dyer, “Daddy Wags Demolished Tribe Hurlers,” Los Angeles Times, December 21, 1963.

15 Dyer, “Daddy Wags Demolished Tribe Hurlers.”

16 Regis McAuley, “Daddy Wags Beats War Drums, Injuns Awaiting Game Hum,” Cleveland Press, June 13, 1964.

17 Donnelly, “Players in the Corner.”

18 Regis McAuley, “Daddy Wags Beats War Drums, Injuns Awaiting Game Hum,” Cleveland Press, June 13, 1964.

19 McAuley, “Daddy Wags Beats War Drums.”

20 Russell Schneider, “Leon Wagner,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 17, 1965.

21 Schneider, “Leon Wagner.”

22 Hal Lebovitz, “Wags Hits Clean-up on Young Toughies,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 20, 1965.

23 Russell Schneider, “Daddy Wags, Playing Regularly, Puts Pep Into Sputtering Indians,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 20, 1966.

24 Russell Schneider, “Daddy Wags Eyes Buckpasser Role,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 18, 1967.

25 Russell Schneider, “Daddy Wags Promises 40 HRs ‘If They Let Me Play,’” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 16, 1968.

26 Russell Schneider, “Indians Obtain Hall and Snyder to Buttress Flychasing Brigade,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 29, 1968.

27 Jerome Holtzman, “Intelligent’ — That’s Wags’ Word for White Sox,” Chicago Sun-Times, July 6, 1968.

28 Regis McAuley, “Daddy Wags Enjoys Minors — Less Pressure, More Laughs,” Cleveland Press, June 21, 1969.

29 Bill Plaschke, “Bitter Ending,” Los Angeles Times, January 25, 2004.

30 Plaschke, “Bitter Ending.”

31 Hal Lebovitz, “Sad Ending,” Lorain (Ohio) Morning Journal, January 11, 2004.

32 Lebovitz, “Sad Ending.”

Full Name

Leon Lamar Wagner

Born

May 13, 1934 at Chattanooga, TN (USA)

Died

January 3, 2004 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.