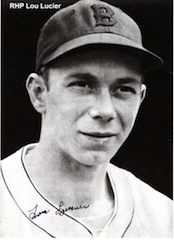

Lou Lucier

From New England’s Blackstone Valley textile mills sprang Second World War pitcher Lou Lucier, a trim 5-foot-8 right-hander weighing 160 pounds with a brief major-league career for the Red Sox and Phillies in the years 1943-45.

From New England’s Blackstone Valley textile mills sprang Second World War pitcher Lou Lucier, a trim 5-foot-8 right-hander weighing 160 pounds with a brief major-league career for the Red Sox and Phillies in the years 1943-45.

Lucier had four brothers and four sisters, born in Northbridge, Massachusetts, on March 23, 1918, to John B. Lucier, a loom fixer in a cotton mill in nearby South Grafton, and his wife, Dena, who was busy enough at home with nine children that she never worked at a job outside the home. “We were all working at one time, so that brought in some money,” he said. The Luciers were of French-Canadian heritage, but the children were all raised speaking English. “My father and mother spoke French to one another, but all the kids spoke English. When they wanted to say something they didn’t want us to know, they spoke in French.” Dena Lucier lived to age 95, passing away in 1980. John died in 1959 of prostate cancer.

Lou’s brothers all played baseball in school but that was as far as they went. Lou was the one with the bug for baseball, beginning in sandlot ball and continuing on to the major leagues. There was no Legion ball in the area when he grew up, but both the mills and towns in the area had active semipro teams. Lucier started pitching during his sophomore year in high school in Grafton.

Despite its being the Depression, Lou was able to start working soon after he graduated from Grafton High School in 1936, and it was baseball that helped. “They had what they called the mill league and that’s the way I got a job. I played ball for a cotton mill — American Weavers, another mill in town. I was what they called a battery hand. In other words, I took cotton bobbins and I put them in what they call a magazine for the people that weaved. I had two sisters that weaved and I used to fill their batteries. Setting up for them. My father was working at the same mill. I pitched on that team.” After some months, he found another, better-paying job in Woonsocket, Rhode Island, not far across the state line from home.

There, he rather soon caught the eye of at least one scout and was signed into the Boston Braves’ system, assigned in 1937 to play in the Pennsylvania State League for the Class D Beaver Falls Bees. The first time he was approached, he hesitated. “This guy, this scout, talked to me after the game and wanted to know if I was interested in playing professional ball. I said, ‘I think I’m too young [He was 19]. I don’t think my father would let me go in.’” The second time he was asked, though, “I finally decided my father was going to let me go.”

His stay in Beaver Falls was a short one, 14 innings over four games, with a 1-0 record. “I was with the Braves very, very briefly. That didn’t work out at all because I didn’t care for it,” he said. It was back to the mills in Woonsocket, and Lou was very active with the semipro team there. The team’s name was something of a mouthful: American Wringer Taft-Peirce. It was a cotton worsted mill, and he worked on equipment called the drawing frame.

Lou also met someone special at one of the games, Marcella Ouellette. “I met a girl at a baseball field there when I was pitching for Woonsocket. She was just at the ballgame with one of her sisters. I happened to see her after one of the games that I pitched in Rhode Island. We got together, and finally after two years, we got married.”

The Woonsocket team was very successful, state semipro champion in 1940 – the American Wringer-Taft-Peirce Combines beat the Greenville Townies in a best-of-three playoff. Lucier pitched the final game and won, 11-2, striking out 13 and allowing only three hits. He was selected an All-State pitcher, and as state champion Woonsocket had the opportunity to participate in the 1940 National Baseball Congress tournament in Wichita, Kansas. The Combines played four games in the tournament and Lou took part in all four. In the first, Woonsocket beat a Massachusetts team, the Worcester Nortons, 7-4. Lou struck out seven and drove in two runs. He didn’t pitch in the next game, but played second base later in the game and was 1-for-1 at the plate. In the third game, the Combines beat the Boomers of Stillwater, Oklahoma, by a 1-0 score, the run scoring in the bottom of the 10th inning. Lucier struck out eight and held the Boomers to five hits. In the fourth game, he had perhaps been overused, or was simply overmatched. The Wichita Stearmans shut out Woonsocket, 7-0. Lou gave up all seven runs on six hits over the first five frames.

The successful season had caught the eye of Red Sox scout L.E. “Jap” Haskell, and he approached Lucier. “One Sunday he called me and asked me if he could come up and talk to me. I said, ‘Yeah, while you’re at it, why don’t you come up and have lunch with us?” So he decided he would. I told him where I lived in Woonsocket. He came up at noontime that Sunday. He came up and that’s when he started to talk to my wife and I. My wife was a real baseball fan. Good thing she did (sic), because she’d have been in trouble. And she wanted me to go play with the Red Sox farm team, although she was a Yankees fan, believe it or not. I went. … Of course, that’s when they sent me to Canton. And I had a manager by the name of Pat Patterson.”

He had a terrific year with the Class C (Middle Atlantic League) Canton Terriers, running up a 23-5 record, with a 1.49 earned run average in 247 innings of work. He was far and away the best pitcher on the team, Bill Voiselle’s 10 wins second in wins and Fritz Dorish’s 3.22 ERA second-best in earned runs.

“Then the following year, I got a call from Fenway Park in Boston. I lived so close to it. I was only 40 miles away, where I lived. They called me in. Joe Cronin, Tom Yawkey wanted to see me, so I got in my car and drove down there, with my wife. She didn’t go in to talk with them with me. I went in by myself. They give me a big bonus there. They gave me a thousand dollars because I had such a good year at Canton. Of course, you didn’t make no money playing in Canton. So they decided that they were going to send me to Louisville, which was Triple A.” The Louisville Colonels were actually Double A — Triple A didn’t exist then – but they were the highest-level team in the Boston system. It was a major jump, all the way from Class C to being one rung below the major leagues.

With Louisville in 1942, Lou played under manager Bill Burwell (“he was a prince”) and was 13-9 with a 2.45 ERA. With the Colonels, he got off to a nice start, two-hitting the Columbus Red Birds on April 19, beating them 4-2 while driving in two of Louisville’s runs. Lucier and Nels Potter were the two aces for the Colonels, Potter recording five more wins with a marginally lower 2.60 ERA. At the time, ERA wasn’t a statistic that evaluators looked at – they had a sense of how well a pitcher performed, of course, but there was no talk of pitch counts or ERA at the time.

Lucier suffered three serious injuries, one each year from 1941 through 1943. On September 8, 1941, while pitching for Canton against Akron in the Middle Atlantic league playoffs, he was throwing hitless ball for the first three innings but was struck on the head while breaking up a double play and knocked unconscious by a ball thrown by the Akron shortstop. “I didn’t see the ball,” he said, “and, boy, I didn’t see anything after that.” Though he had to leave the game, Lucier was back and pitching the next day, throwing another three innings. On September 12, he won the final game of the playoffs, Canton over Erie, 8-3. For “Little Louie,” it was his 24th win of the year. Erie beat Canton, though, taking four out of five – Lucier’s was the only game that the Terriers won. [The Sporting News, September 18 and 25 1941]

In 1942, he was hit by a line drive off the bat of Jo-Jo Moore while pitching in Indianapolis, and says he was in the hospital a full week. The blow was severe, and did sufficient damage to exempt him from military service. “It deafened one of my ears. In fact, it’s still deafened today. My right ear got deafened by it, and they were very strict in who they picked in them days. They said on account of my bad ear, they couldn’t accept me. I can hear a buzz and a hum. Oh yeah. I’ve still got that hum today.”

With rosters depleted as many major leaguers took work in defense plants or entered the service, the Red Sox were looking for talent. Heading into 1943, a headline in the Christian Science Monitor summed up the situation all ball teams found themselves in: “Red Sox, Braves Getting Low on Playing Talent.” Ed Rumill’s article in the January 28 edition of the Monitor joked that the Fenway front office might have to suit up, as well as Tommy Cummings and his peanut vendors. The Red Sox had 28 players they were planning to bring to camp. The pitchers were Mace Brown, Ken Chase, Joe Dobson, Tex Hughson, Norman Brown, Oscar Judd, Dick Newsome, Mike Ryba, Andy Karl, Al Olsen, and Lucier – and Rumill noted that Judd was working in an important part of the Canadian war effort so might not be available. Many of 1942’s stars, like Ted Williams and Johnny Pesky, had already begun their military service. Who did the Sox have for outfielders? Pete Fox, Tom McBride, Ford Garrison, and Johnny Lazor. Rumill admitted, “The writer is no more familiar with the last three than you are.” The Sox did make a move to sign 41-year-old veteran (and future Hall of Famer) Al Simmons, but how much help he might offer was anyone’s guess. Not much, as it happened. He got into 40 games but hit only .203.

Herb Pennock oversaw Boston’s farm system at the time and he liked Lucier, living in Woonsocket, R.I., at the time, so “he will get every chance to make the grade,” wrote Jack Malaney in the March 4, 1943, issue of The Sporting News. Given his minor-league record, Lucier was bound to get a look in any event, but it was obviously easier to make the team considering the situation in wartime.

Invited to spring training with the big-league club in 1943, he didn’t have far to travel. Though the team had trained in Sarasota since 1933, wartime travel restrictions saw the Red Sox train a few miles from Fenway Park – at Tufts College in Medford. It was a convenient locale for those who lived in New England. Though there were many fewer in camp than usual, the Red Sox assigned him number 81 and gave number 82 to Johnny Lazor. They’d played together in Louisville. Asked years later why they’d been given such high uniform numbers (only two players had ever received numbers as high as 40 at the time), neither Lazor nor Lucier could recall. Lou switched to number 15 later on, then took 24 in 1944.

The first game Lucier threw in competitive play came in the second game of the exhibition season, on March 4 at Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field. He was the second of three Red Sox pitchers in a 5-0 shutout of the Dodgers. Dobson got the win. Lucier threw the fourth and fifth innings, allowing two hits and walking one.

His first major-league game was on April 23. He pitched the final two innings in Philadelphia, allowing the Athletics one run on a walk and a hit in a game the Sox lost, 5-0. On the 25th, he whiffed three Yankees, but gave up five hits and four walks in 3 1/3 innings in relief of Ken Chase. His first start was in the second game of a May 16 doubleheader in Chicago. “First game I pitched [started] in the big leagues was against the White Sox, in Chicago. Cronin didn’t want to pitch me at home because he said I might be too nervous, which I don’t think I would have been, but he thought I would. It didn’t bother me. And I had a good day. I had two hits myself. I drove in two runs [actually, he scored two runs], and we won 4-2.”

Lou also had a nice seven-hit, 5-1 win over the Tigers on Memorial Day. Looking ahead to the June 4 Ladies Day game, the Monitor’s Rumill wrote of Lucier that the “pint-sized right-hander … is fast becoming a popular figure at Fenway.” After the game, which he lost despite holding the White Sox to just four hits (five bases on balls were damaging), Rumill wrote, “He can put enough on the ball to win in fast company.” A Monitor proofreader no doubt messed up; Rumill cited the American League Red Book as claiming that Lucier was “six-foot-nine, yet he looks, and probably is, several inches smaller.” The frequent references to his stature never bothered him, he says. “Little Louie, that’s what they called me. No, it didn’t bother me at all. I was making pretty good money then playing ball, compared to working in a cotton mill.”

Battered by the Senators on June 13, he was knocked out of the box after two innings. On Evacuation Day, June 17, Joe Cronin took “little Louie Lucier” off the hook. The Sox were down, 4-1, against the Philadelphia Athletics. There were two on base in the bottom of the seventh, and Lucier due up, so Cronin put himself in as a pinch-hitter and knocked out a three-run homer. What made the day even more remarkable was that Cronin hit another three-run pinch-hit homer in the second game of the day’s doubleheader.

Lou often got battered around; the Yankees got to him for eight hits in 2 2/3 innings on June 27. He was again spared the loss, because Bobby Doerr hit his second homer of the day to tie it in the eighth, then singled in the winning run in the bottom of the 12th. On July 18, he didn’t last the second inning against the Senators, and on the 23rd he was even more roughly treated, though the game wound up a win for the team in 10 innings.

Giving up four hits in one inning of relief on July 26 pretty much sealed Lucier’s fate at midseason and he was optioned to the Colonels on July 30. The Sox sent outfielder Babe Barna down, too, and brought up pitcher Emmett O’Neill.

Another head injury occurred on August 7 when Lucier was struck by a line drive off the bat of Minneapolis’s second baseman. Diagnosed with a concussion of the brain, he was briefly on the danger list and was kept in hospital for two days, prohibited from playing for a full week.

In September, after Louisville’s season was over, Lou was called back up to Boston. He arrived on the 22nd and kicked off with a 3-2 complete-game 10-inning win over the St. Louis Browns on September 26, driving in one of the runs himself, then watching Jim Tabor hit one off the left-field foul pole to win it. Lou lost his last start, on October 3, pounded for 13 hits.

In his first major-league season, Lucier had appeared in 16 games. His W-L record was 3-4 (3.89 ERA) with 23 strikeouts but 33 walks, in 74 innings of work. While with Louisville, he’d thrown 81 innings (6-5, 3.22 ERA) in 14 games.

Lucier delayed signing his 1944 Red Sox contract because he was waiting to hear from his draft board. He was a father of two, and back in South Grafton making machinery for cotton manufacturing at the Whitin Machine Work in South Northbridge, which qualified as a defense plant; under 26, he was subject to the new draft. If he left the plant before his deferment expired on April 20, he could be immediately reclassified 1A. Red Sox GM Eddie Collins said the team was putting no pressure on Lucier, but that he would have to decide which way to go. There would be no weekend baseball accommodation. [The Sporting News, March 23, 1944, and Christian Science Monitor, March 21, 1944] Lucier decided to leave the plant early, report to Bradenton for spring training with Louisville, and take his chances like everyone else in the draft. A physical for the Army was scheduled for April 12; he was rejected because of the concussion he’d suffered at Louisville eight months earlier. He still had missed almost all of spring training, so had very little work. He appeared in three games for the Red Sox, all in relief. He faced 31 batters in 5 1/3 innings, struck out two but walked seven. His 1944 ERA for Boston was 5.06. On May 20, he was optioned to Louisville, where he got a lot of work, throwing 82 innings, posting a 7-3 record (4.83 ERA).

On July 31, 1944, Lucier was sent to San Diego on option, packed off to the Padres with Lazor and pitcher Joe Wood, all to acquire Rex Cecil, who already had 17 wins for San Diego and was leading the Pacific Coast League in strikeouts. Lou was 1-5 with the Padres, with an ERA of 4.50. In September, all three were called back to Boston, but Lou was gone before the month was out. On September 26, the Phillies purchased Lucier from the Red Sox. Herb Pennock had left the Red Sox and was the Phils’ GM, and he wanted Lucier. Lou knew it: “When I got traded to the Phillies, it was on account of Herb Pennock, He got me over there. He really welcomed me when I got off the train.” Lou appeared in relief during the first game of a doubleheader on October 1, the last day of the regular season, against the Pirates. He put on five baserunners in two innings, but it was already a lost cause before he came in (the Phillies lost, 9-1). It was Lucier’s only appearance with the Phillies that year, leaving him with a 13.50 ERA.

In 1945, he appeared in 13 games over the first couple of months, 0-1 but with an excellent 2.21 ERA in 20 1/3 innings. He walked five and struck out five. The Phillies were interested in Cuban pitcher Isidoro Leon, though, and traded Lou with one or two other players in early June, sending them to Mike Kelley’s Minneapolis Millers. On June 9, he debuted against his former Louisville Colonels, a five-hit 3-1 victory. On September 6, he was hurt in a collision at first base and had to be carried from the field but later left the park on his own. With the Millers in Double-A, he won nine and lost five, with an ERA of 5.04.

The next season, 1946, was disappointing. The war was over and large numbers of players came back from the service. Lucier got a shot in the New York Giants system; Minneapolis had become a Triple-A farm club for the Giants. There began to be a little too much moving around, Lucier said: “I figured to hell, they sent me to Minneapolis and everywhere.” He appeared in two games for Minneapolis, then five with Jersey City in the International League. And then Jersey City GM Carl Hubbell sent Lucier to Chattanooga. He balked. “I didn’t want to go,” he said. “I told Carl Hubbell I was going home. ‘No, you’re not,’ he says. ‘I didn’t release you yet.’ I said, ‘Well, I’m going to release myself, then. I’m going to get the next bus home to Rhode Island.’ That’s what I did and he didn’t do anything about it. He was trying to keep me. He figured … somebody told him I still had something, I had a good curveball or something. He said, ‘If you’ve got a good curveball, you can always get the guys out pretty well.’ In fact, that’s what I used to get all the guys out with – my curve. I came back and I played for Providence for half a year [an unaffiliated club in the Class B New England League] and then I quit.

“I went to work in the same plant that I worked at before. Same kind of work. Machinery work. Making machines. Whitin Machine Works. I retired in 1983. That’s when I finished my work anywhere. I get Social Security now, with a small pension from Whitin Machine Works. With the both of them, I can get by.”

Lou and Marcella had three children, a boy and two girls. He never was able to convert her into becoming a Red Sox fan. “I didn’t try to bring her over. She had been like that all her life.” He himself is a Red Sox fan, exclaiming over the telephone, “Oh, Jesus, you should see the Red Sox stuff that I’ve got in here. I like the Phillies a lot, too. They treated me real good.” In 2007, the Red Sox won the World Series and the Phillies followed suit in 2008. “How about that? Yeah, I’m doing pretty good with my former teams.”

Their son is a Sox fan, too, but lost his interest in baseball in his first year of Little League when a screaming line drive back through the box came too close for comfort. Today, he’s a salesman for Sysco Foods, living the next town over from Lou, in Uxbridge. Two years younger, his sister works for Commerce Insurance in Webster, Massachusetts. The youngest daughter lives in Millbury. Both towns are close by Lou.

Lou lost Marcella, but at age 91 in 2009 he had five grandchildren and 14 great-grandchildren. “Every time we’re together, they all talk baseball, That’s all they ever talk. It is nice. You know what, my kids are so good they got me what they call the Baseball Channel around here and I can watch any games I want. I’m legally blind; I can’t read anything. I can’t see pictures. I get around pretty good, though. If I’m sitting about five or six feet away from the screen, I can make it out. They got me a big screen, so I’m all set. I get well taken care of.”

Lucier was the oldest living Red Sox for a considerable period of time, but he died at age 96 on the afternoon of October 18, 2014 at the Millbury Health Care Center in Millbury, Massachusetts.

Sources

For this story, the author relied heavily on a long interviews with Lou Lucier done June 26, June 29, and July 6, 2009, and in several newspaper accounts, mentioned explicitly within the text. Thanks to Jerry Taylor, National Baseball Congress, Wichita, Kansas.

Full Name

Louis Joseph Lucier

Born

March 23, 1918 at Northbridge, MA (USA)

Died

October 18, 2014 at Millbury, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.