Mark Fidrych

Although he pitched in only 58 major-league games in his tragically brief career, Mark Fidrych made an enduring impression on the history and culture of professional baseball. Fidrych had one stellar season, in 1976.That season, he first made an impression on baseball fans with his pitching prowess when he came out of nowhere to become one of the best pitchers in baseball. But it was Fidrych’s antics on the mound, his genuine exuberance in playing the game, and his “just folks” persona that made a permanent impact on the American public and brought Fidrych his lasting fame, making him one of the most inspirational players in the history of the game.

Mark Steven Fidrych was born August 14, 1954, in Worcester, Massachusetts, to Paul and Virginia Fidrych. He grew up in the town of Northboro, Massachusetts, where his father was a public-school teacher. Fidrych went to Algonquin High School in Northboro, where he played baseball as well as basketball and football. Because Mark was held back two years while in elementary school, in his senior year he attended a private school, Worcester Academy; age restrictions would have prevented him from playing sports in public school. While he was not a star pitcher in high school and was not offered any collegiate athletic scholarships, Mark caught the attention of both the Boston Red Sox and the Detroit Tigers on the strength of his hard fastball. On the recommendation of Joe Cusick, the New England scout for the Detroit Tigers, Fidrych was selected in the 10th round of the 1974 free-agent draft.

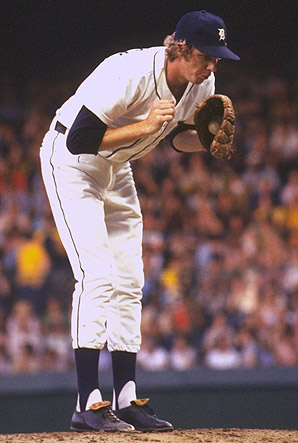

Fidrych began his professional career in 1974, pitching as a reliever in the Appalachian League for the Bristol Tigers. He was tall, at 6-feet-3, and lanky, weighing only 175 pounds, and had a mop-top of curly blond hair. At Bristol Fidrych was given his nickname, “Bird,” by coach Jeff Hogan.1 Hogan thought Fidrych looked like Big Bird from the television show Sesame Street, and the name stuck.

After the 1974 season, Fidrych played winter ball in the Florida Instructional League to prep for the 1975 season. In that season he progressed rapidly through three levels of the Tigers’ minor-league system. He began the year in the Class-A Florida State League as a starting pitcher for the Lakeland Tigers. Although he pitched well, recording 73 strikeouts in 117 innings, he had a losing record, 5-9.2 Fidrych was promoted in midseason to the Montgomery Rebels of the Double-A Southern League. He pitched for Montgomery for only about two weeks and was used exclusively as a reliever. Fidrych was then sent to the Evansville Triplets of the Triple-A American Association, where he once again pitched as a starter. While in Double A and Triple A, Fidrych developed a changeup to go along with his fastball. He also markedly improved his control, walking relatively few batters. In Evansville Fidrych hit his stride, posting an ERA of 1.58 and striking out 29 while walking only 9 in 40 innings. To finish off the season, he started the American Association championship game, going 12 innings for the win. After the season Fidrych again pitched instructional league ball to prepare for the year ahead.

To begin the 1976 season, the 21-year-old Fidrych was promoted to Detroit’s major-league roster. The Tigers had traded their best pitcher, Mickey Lolich, after the 1975 season, and sold Joe Coleman to the Chicago Cubs when the season was two months old, creating openings in the starting rotation. Fidrych began the season in the bullpen and made only two appearances, both in relief, on April 20 and May 5, during the first five weeks of the season. When Coleman came down with the flu and could not make his scheduled start on May 15, Fidrych was given a chance to start at home against the Cleveland Indians. In what may have been his best outing in what proved to be a spectacular pitching season, Fidrych did not allow a hit for the first six innings and pitched a complete game, giving up one run on only two hits and one walk, for his first major-league win. Catching that game was the Tigers’ backup catcher, Bruce Kimm. Because of their success in this game, Kimm became Fidrych’s personal catcher and caught all 29 of his starts that season.

Fidrych had developed into a control pitcher with a good fastball. Ralph Houk, his manager with the Tigers, described him as having “unbelievable control with a fastball that moved.”3 One prominent feature of Fidrych’s pitching was that he worked very fast. Bill James calculated the game time for all starting pitchers in 1976, and found Fidrych to be the fastest-working pitcher in the American League, with an average game time of 2 hours and 11 minutes, 17 minutes quicker than the league average.4

Despite his performance, Fidrych was not yet made a regular starter for the Tigers. Ten days after defeating Cleveland, he started again, versus the Red Sox at Fenway Park. Though he pitched another complete game, Fidrych and the Tigers lost, 2-0, on a two-run home run by Carl Yastrzemski. But based on his strong performance, Fidrych became a regular starter for the Tigers, and won his next eight starts.

Soon after he became a regular starter, sportswriters covering the Tigers began to write about Fidrych’s antics on the playing field. A June 5 article in The Sporting News described him on the mound: “He talks to the ball. … He talks to himself. … He gestures toward the plate, pointing out the path he wants the pitch to take. … He struts in a circle around the mound after each out, applauding his teammates and asking for the ball. … And he’s forever chewing gum and patting the dirt on the mound with his bare hand.” The article quoted Fidrych as saying, “I really don’t know what I do out there. That’s just my way of concentrating and keeping my head in the game.”5

The game that firmly established the legend of Mark Fidrych was one on June 28 against the New York Yankees. The national media had picked up on both Fidrych’s success — he was now 7-1 — and his antics on the field. In turn, baseball fans and the American public were taking notice of the Bird. The game, pitting Fidrych against the first-place Yankees, was televised nationally on ABC’s Monday Night Baseball and received a great deal of attention. Fans came in droves to attend the game at Tiger Stadium; 47,855 people got in, and it was reported that another 10,000 were turned away more than an hour before the game was scheduled to start.6 Fidrych shut down the Yankees, allowing seven hits, no walks, and just a solo homer by Elrod Hendricks as the Tigers won 5-1. Chants of “Go Bird Go!” echoed through the crowd during the game. The Yankees, however, were unimpressed with Fidrych and his nonpitching actions on the field. In particular, Thurman Munson, who did not play in the game because of a bruised knee, was angry and felt that Fidrych was showing up the Yankees. He was quoted as saying, “Tell that guy if he pulls that stuff in New York, we’ll blow his —— out of town.” Willie Randolph, who admitted that he was distracted during his first at-bat against Fidrych, simply said, “You want to send a line drive right through his head.”7

Tigers fans, however, were ecstatic. When the game, ended, Fidrych ran around the infield, shaking the hands of his teammates before going into the dugout and clubhouse to the ovation of the fans. After the game, as a light rain fell on the crowd, the fans did not leave. They chanted “We want the Bird! We want the Bird!” Fidrych finally returned the field, laughing and smiling at the crowd as he tipped his cap to them. Bob Prince, who was announcing the game on ABC, said that in his 35 years in baseball, he had never seen anything like this, and that it gave him goose bumps. Ernie Harwell later wrote that he thought Fidrych to be “the first big-leaguer to take curtain calls on a regular basis.”8

After the game Tigers right fielder Rusty Staub said of Fidrych: “It’s no act. There’s nothing contrived about him and that’s what makes him a beautiful person.”9 Staub continued, “There’s an electricity that he brings out in everyone, the players and the fans. He’s different. He’s a 21-year-old kid with a great enthusiasm that everyone loves. He has an inner youth, an exuberance.”10

His defeat of the Yankees made Fidrych a huge star. Having amassed a record of 9-2 and an ERA of 1.78, he was named the starter for the American League for the 1976 All-Star Game. Fidrych gave up two runs in the first inning of the game and was charged with the loss as the American League lost, 7-1.11 Fidrych bounced back from the All-Star Game loss to finish the season with a record of 19-9 while posting an American League-best ERA of 2.34. He also led the league in complete games, with 24 complete games, including five in extra innings, among his 29 starts. He won the American League Rookie of the Year Award and came in second, behind Jim Palmer, for the AL Cy Young Award. The Tigers finished with a record of 74-87, 24 games behind the American League East-winning Yankees.

When Fidrych started his first game against the Indians, there was a crowd of 14,583 at Tiger Stadium. Against the Yankees that June 28, the crowd was 47,855. For the remainder of the season, whether the team was on the road or in Detroit, huge crowds came to see Fidrych pitch. Three of his starts attracted more than 50,000. Attendance at Tigers games went from 1,058,836 in 1975 to 1,467,020 in 1976, an increase of almost 39 percent.

Despite his stardom, Fidrych still demonstrated his innocence in the world of big-time sports, as evidenced by the contract he signed after the 1976 season. Although agents flocked to him, Fidrych resisted signing with one as he and his father negotiated directly with the Tigers. In the end he accepted a retroactive raise to his major-league minimum contract for 1976, hiking it from $19,000 to $30,000, and received a three-year contact starting at $50,000 for 1977.While the contract put his mind at ease — “Now I can concentrate on playing baseball,” Fidrych declared — many felt he could have demanded far more money.12 Early in the 1977 season, Fidrych appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine. He was among the first athletes to appear on the cover of the magazine (after Muhammad Ali and Mark Spitz), which was then a countercultural and rock-and-roll institution. The article in the magazine described him as having a style that is “singular in baseball, a game which, in any case, doesn’t place great value on singular style.” The article also describes Fidrych as “the embodiment of rock & roll” in baseball.13

During spring training to start the 1977 season, Fidrych injured his knee while shagging flies. He had surgery on the knee and was able to return to the mound on May 27.When he did return, there was great fanfare, including a cover story in Sports Illustrated and a crowd of 44,027 on hand for his first start of the season at Tiger Stadium.14 Although he lost his first two starts of the season, he was as dominant as he had been in 1976, winning six straight games from June 6 to June 29. He pitched complete games in seven of his eight starts. Then, in a game against the Baltimore Orioles on July 4, he felt his arm go dead as he gave up six runs in 5⅔ innings. His arm, and his pitching, would never be the same. He made two more starts, but did not finish the first inning of his final start of the season, on July 12.

In 1978 Fidrych came back to start the season and pitched an Opening Day complete-game win. He followed that with another complete-game win. But by the time he appeared again on the April 24 cover of Sports Illustrated, he had made his third and last start of the season. Still he persisted, making four starts in 1979, but posting an ERA of 10.43. He was limited to nine starts in 1980. He did win his final major-league start, the last game of the 1980 season.

Fidrych even returned to the minors for portions of the 1980 season and all of 1981. After the 1981 campaign he was released by the Tigers but was signed by the Red Sox. He continued to try to return to the majors, pitching in the minors for the Pawtucket Red Sox in 1982 and 1983. But his pinpoint control was gone and he walked far more batters than he struck out. He finally retired from baseball on June 29, 1983, at the age of 28. An article in The Sporting News said Fidrych tried everything short of surgery in an attempt to find a solution to the recurring tightness in his shoulder.15 In 1985 Fidrych went to see Dr. James Andrews, who diagnosed him with a torn rotator cuff and successfully operated to repair his shoulder. However, it was too late for a comeback.

It is easy to speculate what brought about Fidrych’s career-ending injury. The knee injury before the 1977 season may have precipitated a change in his pitching motion which in turn may have caused the tear in his rotator cuff. There is certainly no question that he threw a high percentage of complete games in his starts. In the period 1976-1978, Fidrych threw complete games in 77 percent (33 of 43) of his starts. Although pitch counts for his starts were not recorded, the number of batters he faced can be calculated. In 1976 Fidrych faced 34 or more batters in 17 of his starts. Given an approximate average of 3.5 pitches per batter faced, Fidrych, at age 21 with one full season in the minors behind him, was likely throwing more than 120 pitches in most of the games he pitched. In one game he faced 47 batters, which meant that he threw approximately 165 pitches. Regardless of the cause, Fidrych’s career was cut severely short by his injury.

Fidrych went back home to Northboro, Massachusetts, where he became a licensed commercial truck driver and later purchased a farm. He married his wife, Ann, in 1986, and they had a daughter, Jessica.16 He made appearances for charity groups and nonprofit organizations over the years, making himself rather accessible to fans who fondly remembered the career of the Bird. Tragically, Fidrych died on April 13, 2009, at age 54, in an accident as he worked underneath a truck.

Both before and after his death, Fidrych remained in the consciousness of America. He was the inspiration behind, among other things, a coloring book on his career;17 a unique autobiography, titled No Big Deal, that he co-authored after the 1976 season;18 a poem by his biographer, Tom Clark;19 an independent film, Dear Mr. Fidrych, written and directed by Mike Cramer, a lawyer from Chicago;20 and the song “1976” by the band the Baseball Project.21 Each of these works reflects the exuberance, idealism, innocence, humility, and greatness found in the career and life of Mark Fidrych.

Fidrych and fellow pitcher Al Hrabosky played bit parts in the 1985 movie The Slugger’s Wife, which — although written by the acclaimed playwright Neil Simon — was panned critically.22 Fidrych played a much greater role in the movie from 2009, Dear Mr. Fidrych. As one might assume from the title, this film was greatly inspired by Fidrych and features him primarily as an unseen character, but also includes him playing himself for a brief but significant segment. The storyline follows a boy, Marty Jones, from the Detroit suburbs who comes to love Fidrych in 1976 and mails him a poem. Fidrych writes back, inspiring the youthful baseball career of the boy. The movie then moves forward 30 years, with Marty now going through something of a midlife crisis and embarking on a road trip with his son. At the suggestion of his son they decide to travel to Massachusetts and try to meet Fidrych. They arrive at Fidrych’s farm, meet the father’s boyhood hero, who is generous with his time and wisdom, and even play catch with him. While the movie was a low-budget ($30,000) dream project of its creator, with himself and his family playing the leading roles, it has a big heart, much like Fidrych himself.23 Fidrych died weeks before the movie was first screened.

After his playing career ended, Fidrych was never bitter about his shortened career. He always referred to himself as “lucky,” saying, “I got a family, I got a house, I got a dog. I would have liked my career to have been longer, but you can’t look back.”24

An updated version of this biography appeared in “From Spring Training to Screen Test: Baseball Players Turned Actors“ (SABR, 2018), edited by Rob Edelman and Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 Mark Fidrych and Tom Clark, No Big Deal (New York: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1977), 82-83.

2All playing statistics were accessed at baseball-reference.com.

3 Bill James and Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2004), 203.

4 Bill James, 1977 Baseball Abstract (self-published, 1977), 37.

5 Jim Hawkins, “The Bird Amuses Tigers, Befuddles Enemy Swingers,” The Sporting News, June 5, 1976: 8.

6 Jim Benagh and Jim Hawkins, Go Bird Go! (New York: Dell Publishing, 1976), 142.

7 Pat Calabria, “Yanks Object to a Presentation,” Newsday, June 29, 1976: np.

8 Ernie Harwell, “Mark Fidrych,” in Danny Peary, ed., Cult Baseball Players (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1990), 323-327.

9 Calabria.

10 Thomas Rogers, “Rookie Hurls 7-Hitter for 8-1 Record,” New York Times, June 29, 1976: 37-38.

11 Lowell Reidenbaugh, “Insult Added to Injury: AL’s Sad All-Star Fate,” The Sporting News, July 31, 1976: 5.

12 Jim Hawkins, “Bird a Tabby Cat at Contract Table,” The Sporting News, October 30, 1977: 20.

13 Dave Marsh, “The Tale of the Bird,” Rolling Stone, May 5, 1977: 42-47.

14 Peter Gammons, “The Bird Flaps Again and Doesn’t Flop,” Sports Illustrated, June 6, 1977: 20-21.

15 “Fidrych, Facing Cut, Chooses Retirement,” The Sporting News, July 11, 1983: 45.

16 Bryan Marquard, “Mark ‘The Bird’ Fidrych, 54; Pitcher Enthralled Fans,” Boston Globe, April 14, 2009: B14.

17 Rosemary Lonborg and Diane Houghton, The Bird of Baseball: The Story of Mark Fidrych, A Coloring Book (Northboro, Massachusetts: Fidco Distributors, 1996).

18 Fidrych and Clark.

19 The poem can be found in Richard Grossinger and Lisa Conrad, eds., Baseball I Gave You All the Best Years of My Life, Fifth Edition (Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books, 1992), 90.

20Dear Mr. Fidrych, An Independent Film by Mike Cramer, Monkeydog Media LLC, 2009.

21 The Baseball Project, “1976,” (written by Steve Wynn), Volume 2: High and Inside, Yep Roc Records, 2011.

22 One such critical review can be found at: rogerebert.com/reviews/the-sluggers-wife-1985, accessed January 2, 2017.

23 Phone interview with Mike Cramer by Richard J. Puerzer, January 25, 2012.

24 Marquard.

Full Name

Mark Steven Fidrych

Born

August 14, 1954 at Worcester, MA (USA)

Died

April 13, 2009 at Northborough, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.