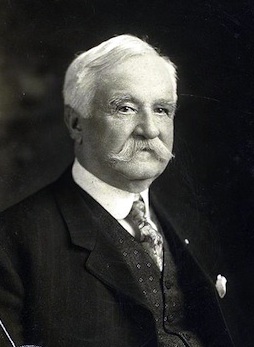

Morgan Bulkeley

There’s a bridge that stretches across the Connecticut River, connecting Hartford with its satellite city, East Hartford, the name of which was changed almost a hundred years ago from the Hartford Bridge to the Bulkeley Bridge. And no doubt, the majority of the 142,000 motorists that transverse this particular bridge on a daily basis, haven’t an inkling as to the origin of its name.

There’s a bridge that stretches across the Connecticut River, connecting Hartford with its satellite city, East Hartford, the name of which was changed almost a hundred years ago from the Hartford Bridge to the Bulkeley Bridge. And no doubt, the majority of the 142,000 motorists that transverse this particular bridge on a daily basis, haven’t an inkling as to the origin of its name.

A few may know that Bulkeley was the governor of Connecticut at some point in the state’s distant past, while some may even be aware that he was also the mayor of Hartford. But not many residents of the Nutmeg State are also aware that he was an early founder of Hartford baseball, the first president of the National League, and one of the earliest inductees into baseball’s Hall of Fame.

On the day after Christmas 1837, Morgan Gardner Bulkeley was born in East Haddam, Connecticut, into a long-established and privileged family, both his parents claiming to have descended from passengers on the Mayflower. In 1846, Morgan’s father Eliphalet, a prominent member of the state’s Republican party, moved with his wife, Lydia Smith (Morgan) and their family, to Hartford where he helped found the Aetna Life Insurance Company, becoming its first president in 1853. Young Morgan got his first job there, sweeping floors along with his brother Charles for a dollar a day. Soon after, Morgan went to work for his uncle at H.P. Morgan & Company in Brooklyn as an errand boy, graduating to the position of salesman, later becoming a partner in the firm. When the Civil War broke out, the Bulkeley brothers joined the army, Morgan with the 13th New York Volunteers, serving under General George McClellan. And though he managed to return home safely, his brother Charles was not so lucky, losing his life in the war.

Back in Brooklyn, Morgan returned to work at Morgan & Co. but came home to Hartford at his father’s passing in 1872; once there, he helped to organize the United States Bank of Hartford and became its president. It was during this period that Morgan Bulkeley first became involved with professional baseball. In 1874 he formed the Hartford Dark Blues of the National Association (famed for fielding Hall-of-Famer Candy Cummings, the purported developer of the curve ball, along with the player who sported one of baseball’s all-time great nicknames, Bob “Death to Flying Things” Ferguson.) When the National League was formed in 1876 and the Dark Blues became a charter member, Morgan Bulkeley was named the first president of the fledgling circuit.

But Bulkeley was not accorded this honor due to any strong ties within the baseball community. In truth, the new league was the brainchild of Chicagoan William Hulbert, but the highly provincial world of early professional ball dictated that naming an Easterner to the post would be the most propitious political move.

As a matter of fact, Bulkeley warned that he would only serve in the position for one year, his business interests and long-time involvement with harness racing taking up much of his professional time. And though he kept his promise of serving just that one-year term, (Hulbert talking over the reins the following season), Bulkeley used his position to help reduce illegal gambling, out-of-control drinking, and overall fan rowdiness within the sport.

And for better or worse, thus ended the baseball career of Morgan Bulkeley save for one last appointment: in 1905 he was named to the Mills Commission, the panel whose questionable findings about the origins of baseball are still being debated today. Bulkeley went on to serve on the Common Council and the Board of Aldermen before finally becoming president of Aetna when his father’s successor was forced to retire due to health issues in 1879. It was a position he would hold for the rest of his life, and Aetna continues to be at the foundation of Hartford’s business community.

In 1880, Bulkeley ran for both mayor of Hartford and governor of Connecticut, losing the latter election, but serving as mayor of the capital city for four two-year terms. Known for his generosity, Bulkeley, was said to have run steamboat trips for needy children up the Connecticut River during his time in office and paying for it out of his own pocket. And it was during his administration that he met and married Fannie Briggs Houghton in February of 1885, though he was already 47. Nonetheless, the union produced three children, two boys and a girl.

In 1888, Bulkeley decided to run for governor again, and this time he was successful, though the election proved controversial. When no candidate had accumulated at least fifty percent of the popular vote, the state’s Republican-leaning General Assembly had the responsibility of choosing the next governor, and they chose Bulkeley. But when he tried to run for re-election two years later, the battle became embroiled in such a morass of illegalities, confusion, and voter fraud, that Bulkeley refused to cede the victory to the Democratic candidate and found himself locked out of his office the morning after the election by the Democratic state comptroller. Grabbing a crowbar, Bulkeley broke into the room, thereby gaining the nickname The “Crow-Bar Governor.” He served in the post for two more years, despite the fact that he had never really earned re-election! And though during this term the state Supreme Court finally ruled that he was indeed the lawful governor for this disputed period, the legislature failed to provide any funding while he was in office, and Bulkeley was forced to borrow money from Aetna to pay the state’s bills.

Not dissuaded by his experience in state politics, Bulkeley went on to serve a term in the U.S. Senate from 1905 to 1911, where he faced more political conflict, this time battling with the sitting President, Theodore Roosevelt. In 1906, members of an African-American battalion, the 24th Infantry Division of Brownsville, Texas, were accused of rioting and disorderly conduct. When none of the arrested soldiers would testify against their comrades, TR dismissed the entire battalion with a dishonorable discharge and Bulkeley became one of the few U.S. Senators to publicly oppose the President’s decision. (The case, interestingly, was decided long after the participants were gone: in 1972, the Army reviewed the case and granted the soldiers posthumous honorable discharges.)

Bulkeley continued at the head of his powerful company until his death on November 6, 1922, at the age of 84. Under his stewardship, Aetna grew to become the largest insurance firm in the country, increasing its assets during his 43-year tenure from 25 to 207 million dollars.

In 1937, fifteen years after his passing, it was decided that Morgan Bulkeley would be installed in the National Baseball Hall of Fame, at its ceremonies scheduled for 1939. Once again, however, it was more of a “political” decision than a baseball one: as American League founder and president Ban Johnson had been chosen for induction at that time, it was felt that the National League also needed to be represented. Hence, as the NL’s first chief executive, Bulkeley seemed the logical choice.

Additionally, upon his death, the Hartford Bridge was re-dedicated in his honor. The only question that remains is how much the thousands of motorists who cross that span every day know about the man for whom it had been named.

Sources

Connecticut State Library material on Bulkeley as governor

Full Name

Morgan Gardner Bulkeley

Born

December 26, 1837 at East Haddam, CT (US)

Died

November 6, 1922 at Hartford, CT (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.