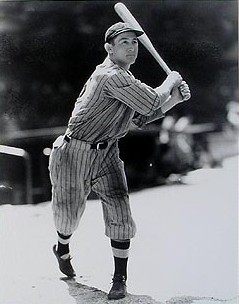

Odell Hale

Odell Hale had a few nicknames. First came “Sammy,” but early in his first year in baseball he became “Bad News” – and he was also sometimes called “Chief.” His death certificate indicates the nickname “Bing.” Hale himself listed his nationality as “Irish and Indian” on the questionnaire he completed for the Hall of Fame (and he wrote on the form that his nickname was “Bad News”).

Odell Hale had a few nicknames. First came “Sammy,” but early in his first year in baseball he became “Bad News” – and he was also sometimes called “Chief.” His death certificate indicates the nickname “Bing.” Hale himself listed his nationality as “Irish and Indian” on the questionnaire he completed for the Hall of Fame (and he wrote on the form that his nickname was “Bad News”).

Coming from Caddo Parish in extreme northwestern Louisiana, he likely had some Choctaw blood or, perhaps, Apache. His given name was Arvel Odell Hale, though even in United States census reports he was always listed as Odell. Hale was born on August 10, 1908 or 1909 in Hosston, Louisiana, where he attended 11 years of elementary school and high school, playing baseball and basketball at Hosston High School, but – according to a number of stories – he wasn’t interested in much more than “to stand in an infield and take them as they came.”[1]

His parents, James Monroe “Jim” Hale and Ella Stanberry Hale, were farmers – Jim a native of Louisiana and Ella hailing from Arkansas. They began and ended the naming of their children with common names – Stephen and Marie – but in between they had quite a stretch – Claud, Ovida, and Arvel Odell. He himself provided the 1909 year of birth, and it was the year indicated throughout his career. His death certificate gives the date as 1908. He was 5-foot-10 or 10 ½ and listed his playing weight at 165-175 pounds. Older brothers Stephen and Claud found work as a carpenter and railroad agent, respectively. Odell was the only one in the family to play pro ball.

In 1930, Hale married a Native American, Mabel Jane Rainwater from Oklahoma, who was working at a clerk in a drug store in El Dorado, Arkansas, when they first met in 1928. At age 17, Hale had taken a job working at a refinery in El Dorado and was working as a tank car loader for the Lion Oil Company when he met his future wife. He had been playing semipro ball with the refinery team, and a little in Little Rock, too.

Their daughter Dorinda confirms that Hale, too, had Native American ancestry, but she doesn’t know the nation(s) or tribe(s) in question. “I wish I had asked those questions a long time ago,” she lamented late in 2007. Her brother Buzzy added, “He had a pretty rough childhood. His mother and dad died early. He just never talked about his childhood with us.” [2]

Hale was a right-handed infielder who played 10 years in the major leagues, the first nine of them with the Cleveland Indians. Except for one of his 1,062 games, when he played shortstop in 1931 he was either a second baseman or third baseman, or served in a pinch-hit or pinch-run capacity. A solid hitter with a lifetime .289 average and a .352 on-base percentage, his best years were 1934-36 when he averaged over .300 and drove in 101 runs twice.

The first team Hale played with was the 1929 Alexandria Reds in the Class D Cotton States League, where he played third base (the manager, Pete Kilduff, was the team’s second baseman). Hale hit for a strong .324 average, and led the league in runs scored with 116. Under Kilduff, Alexandria (74-50) placed first in the eight-team league. At the very end of the season, he was among several players who got called up to Shreveport and he appeared in three games for the Class-A Texas League team.

It was Hale’s clutch hitting and home-run power (23 round trippers on the year) that won him attention – and also a shotgun on July 31, presented by the mayor of Alexandria after a homer early in the game. After play was resumed, Hale homered each of his next two times at bat. [3] Back in early June, when he first broke in, he crashed out home runs on five consecutive days, earning him a degree of national attention. [4] Local sportswriters claimed he was bad news for opposing pitchers –and he’d picked up his most enduring nickname.

This was Class D baseball, but the Chicago Cubs took note of his season – and that of teammate, pitcher Lon Warneke, and purchased both their contracts. [5]

Promoted to Class B, Hale spent 1930 in the Three-I League (Illinois-Indiana-Iowa), where he hit .316 in 129 games for the Decatur Commodores, though with less power – eight homers. Decatur finished third. Hale got bumped up to A ball.

The 1931 season began with the Southern Association’s New Orleans Pelicans, and Hale hit .310. He hit just one home run, but he did enjoy a four-hit game against Little Rock and the one fame that stuck with him as his most memorable game, a five-hit game against Mobile. And he got a chance to see some action in the big leagues, debuting on August 1 with the Cleveland Indians, entering late in the game as a replacement at second base. The next day, he started his first game, playing second base in both games of a doubleheader against the Browns. Hale batted second in the order and was 1-for-5 in the first game and 2-for-6 in the second, with a single and a triple in those six at-bats, scoring three runs. His first RBI came on his first home run, on August 9 against Chief Hogsett of the Tigers. He collected 92 at-bats before the season was out, batting .283 in 25 games for manager Roger Peckinpaugh, with just the one home run and a total of five RBIs.

The Toledo Mud Hens of the American Association were his assigned team in 1932, with Hale gaining more seasoning while playing a full 158 games at Double A and batting .333 with seven homers. Fielding was never his forte; he committed 42 errors with Toledo, though he’d previously cut his totals from 48 with Alexandria to just 13 with the Pelicans. When he returned to the majors, he led the league in errors at his position in both 1934 and 1935 but his fielding improved dramatically starting in 1937, and his overall fielding percentage of .953 isn’t bad. He preferred to play third, but most baseball men believed he was better at the keystone sack. [6]

Cleveland brought him back to the big leagues in 1933, and he stuck as a major leaguer through the 1941 season. Walter Johnson replaced Peckinpaugh as skipper after the first third of the season. It was a good solid year in 1933, batting .276 in 351 at-bats. He hit 10 homers and drove in 64 runs. The next three years, he really shone, playing almost every game and hitting over .300 each year, with his share of game-winning hits and with both an on-base percentage and a slugging percentage which increased each of the three seasons. Hale was surrounded with other .300 hitters in the lineup – Hal Trosky, Earl Averill, and Bill Knickerbocker – for all three years. Hale drove in 101 runs in both 1934 and 1935; in 1936, he drove in 87.

Particularly after the ’35 campaign, in which he stole a career-high 15 bases (but was caught a league-leading 13 times), he was of real interest to both the Red Sox and the Yankees, and the Indians would have been prepared to deal, had there been an offer deemed good enough. [7] In fact, The Sporting News of January 30, 1936, declared that the Indians were faced with “enthusiastic efforts of every other club in the league” to entice Hale away from them.

Knickerbocker was gone by 1937 and all three of the others (Trosky, Averill, and Hale) had significantly sub-par seasons. Hale hit .267, while both of the others were a hair below .300.

Hale’s most renowned moment in baseball came when he took part in a September 7, 1935, bases-loaded triple play against the Red Sox. Joe Cronin hit a screaming liner to third base, hit so hard that Hale couldn’t get his glove up in time. The ball hit off his forehead and, seeing the misplay, the runners took off. But the ball deflected into shortstop Knickerbocker’s glove; he threw to second base, where Roy Hughes stepped on the bag and threw to firstbaseman Hal Trosky, doubling up both baserunners. The play ended the game, the first of a double-header. Needless to say, any number of stories on the “that’s using your head” theme followed the triple play. Al Schacht said, “The most astonishing thing was that the ball wasn’t damaged in the slightest.” [8] Hale himself had suffered no ill effects; the very next day, he hit a game-tying homer and the September 18th New York Times noted that he was still “Hale and hearty” in the immediate aftermath.

In both 1938 and 1939, Hale played fewer games (130 and then 108) but saw his average and OPS climb again each year, to a .312 batting average in 1939 (OPS of .813). He’d developed a sore arm in 1938, and it hampered him more in ’39. He was never out with an injury for any period of time; he just worked fewer games. His arm had come around and he’d finished strong in the field. In 1940, he saw much less work, batting almost exclusively in pinch-hitting roles, only twice having more than one at-bat in a game, and only gathering 55 plate appearances in 48 games. He didn’t hit all that well, either – batting just .220, driving in six runs and only scoring three.

Less than a month after Roger Peckinpaugh began his second stint as the new manager of the Indians, the team engineered a six-player swap with the Boston Red Sox. There had been discussions between the two teams as far back at late 1938, but they finally came to fruition in the December 12, 1940 trade. The Red Sox sent Doc Cramer to the Senators for Gee Walker, then traded Walker, Jim Bagby Jr., and Gene Desautels to the Indians for pitcher Joe Dobson, catcher Frankie Pytlak, and Hale, who frankly just balanced the deal out a bit. News stories about the trade barely mentioned him – despite a nine-year batting average of .293 for the Tribe. Cleveland had just missed winning the pennant in 1940 by one game; they felt this deal could put them over the top in 1941. The Red Sox also felt they’d improved their own chances.

Hale only appeared in 12 games for Boston, though, finally nudging his average up to just over .200 (five hits in 24 at-bats) before being placed on waivers and claimed by the New York Giants on June 19. He played with the Giants until Labor Day, but was hitting just .196 and after the September 7 doubleheader, his contract was sold to Bill Veeck’s Milwaukee Brewers in the American Association. He’d finished his major-league career. In 1942, Hale appeared in 62 games for the Brewers, batting an even .250 but it was time to call it a day.

After the brief stint with Milwaukee, he took a position with a defense plant in El Dorado, Arkansas, a firm that was later bought up by Monsanto Chemical and where Hale worked as a senior operator until retirement.

At age 71, Hale suffered a cerebral stroke and was admitted to an El Dorado Nursing home, where he died two weeks later of a suspected pulmonary embolism.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Hale’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the online SABR Encyclopedia, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com. Some of this material was originally published in the book Red Sox Threads.

[1] Unattributed July 4, 1933 news clipping found in Hale’s Hall of Fame player file.

[2] Interviews with Dorinda and Odell Hale Jr. in 2007

[3] Washington Post, August 2, 1929, and The Sporting News, October 20, 1938

[4] New York Times, June 11, 1929

[5] Washington Post, August 24, 1929

[6] The Sporting News, October 3, 1936

[7] The Sporting News, November 28, 1935

[8] New York World-Telegram, January 23, 1936

Full Name

Arvel Odell Hale

Born

August 10, 1908 at Hosston, LA (USA)

Died

June 9, 1980 at El Dorado, AR (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.