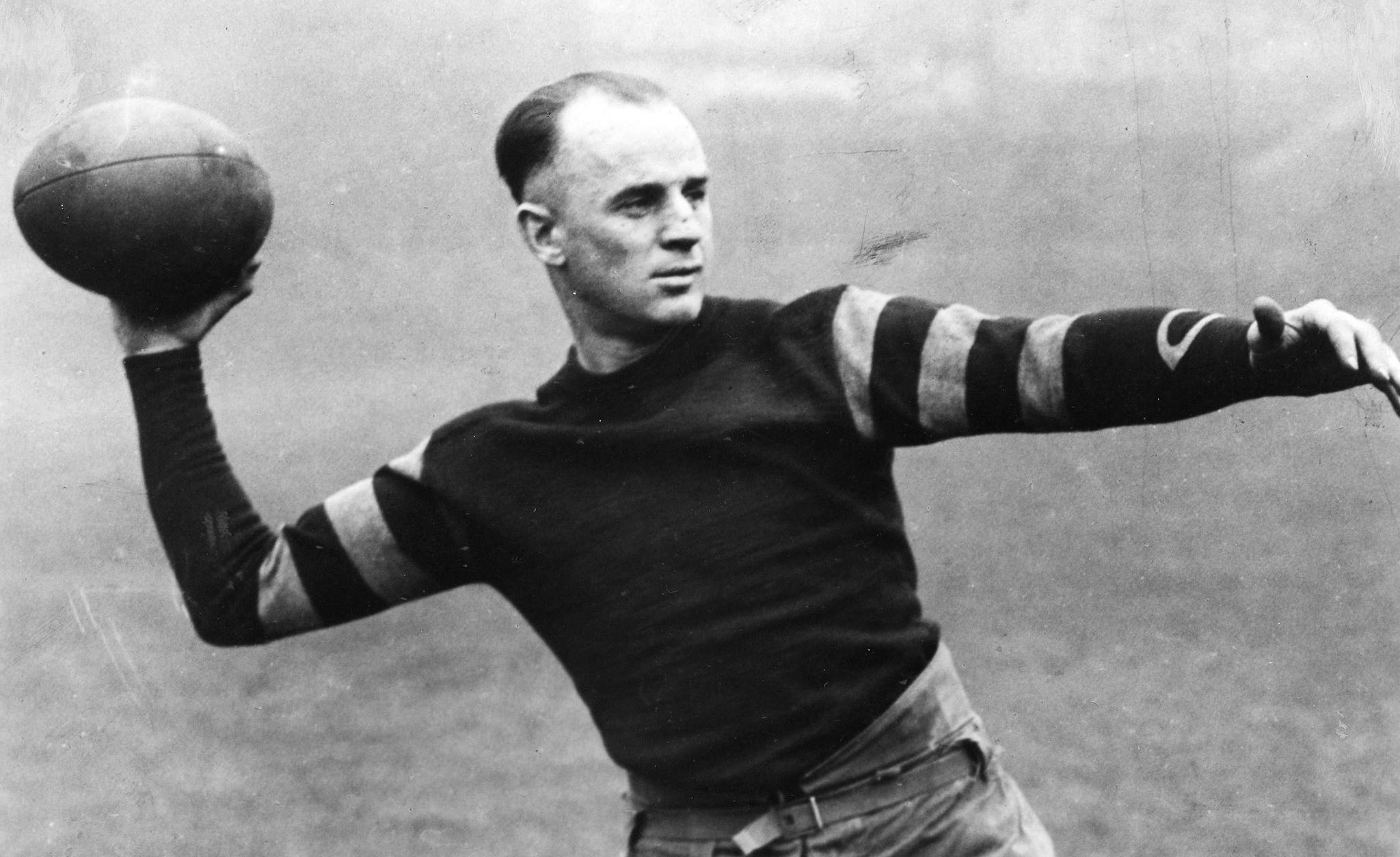

Paddy Driscoll

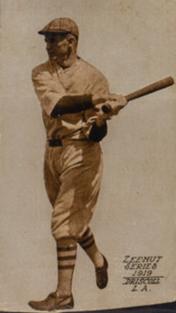

John Leo ‘Paddy’ Driscoll went directly from the purple uniform of Northwestern University to the Chicago Cubs in 1917. The diminutive infielder had been a three-sport star at Evanston (Illinois) High School before lettering in two sports at Northwestern.1 He played one season with the Cubs before entering the Navy during World War I. Back from the war, he played briefly with the Los Angeles Angels in 1919.

John Leo ‘Paddy’ Driscoll went directly from the purple uniform of Northwestern University to the Chicago Cubs in 1917. The diminutive infielder had been a three-sport star at Evanston (Illinois) High School before lettering in two sports at Northwestern.1 He played one season with the Cubs before entering the Navy during World War I. Back from the war, he played briefly with the Los Angeles Angels in 1919.

Driscoll’s real love was football, and he gave up a professional baseball career to concentrate on the gridiron. It was a wise choice, because in September 1965 he joined fellow Northwestern great Otto Graham and five others for induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio.

Timothy and Elizabeth (Mahoney) Driscoll married in 1893 and took residence in Evanston. They welcomed their first child, John Leo, on January 11, 1895. Timothy was an immigrant from Ireland and his wife was a first-generation Irish lass. Over the years Timothy held various positions with a local railroad, working as a stone-cutter, mason, and then foreman. The family would add three daughters and another son.

Paddy played football, basketball, and baseball at Evanston High School. During his induction in Canton he pondered how a fellow who was “128 pounds in high school” could get an honor like that.2 Exactly what size he was is open to interpretation. He listed himself at 5-feet-9 and 160 pounds on a questionnaire filled out in the early 1960s for the Baseball Hall of Fame. Baseball Reference lists him at 5-feet-8, while Football Reference has him at 5-feet-11. While he played professionally, his weight hovered around 150.

When Driscoll began his career, Northwestern played in the Big Nine, a precursor of the Big Ten.3 The team’s biggest rivals were the University of Chicago. The league had rules limiting the number of sports a student could engage in. Consequently, Driscoll played football and baseball and had to forgo varsity basketball collegiately.

Driscoll started in football in 1915 as a defensive back and halfback. He had excellent speed and was a tenacious tackler on defense. Offensively he was switched to quarterback in early November in time for the game with Missouri. The results were a 24-6 victory, only the second of the season. Teammates elected Driscoll captain for the 1916 squad.4

Driscoll returned to halfback for the 1916 season. On October 21 Northwestern took on archrival Chicago (aka the Maroons). Northwestern had been dominated by the Maroons in recent seasons and had not scored against them since 1911. Prospects for a victory in 1916 seemed dim as “the Purple eleven was hopelessly outweighed and outclassed,” according to prognosticators, who expected yet another Chicago win.5

The game was played at Stagg Field (named for Chicago coach Amos Alonzo Stagg) and Driscoll showcased the full range of his talents. His running was highly effective both on plunges and sweeps, “his punting could scarcely have been excelled and it was finally his dropkick which made the Northwesterners in the stands begin to realize the game was theirs.”6 Driscoll’s Purple emerged with a 10-0 victory.

Despite the best efforts of athletic trainer (and former major-league pitcher) Willie McGill, an ankle injury sidelined Driscoll and his backup for the game with Iowa on November 10. Northwestern persevered to win 20-13. Paddy returned to the lineup for a 38-6 trouncing of Purdue. The stage was now set for a battle of the unbeatens at Ohio State. The Buckeyes proved to be too strong, winning 23-3. Northwestern closed at 6-1. It would be 10 years before a Northwestern gridiron team won more games.

Driscoll played baseball for coach Willie McGill in 1916 and 1917. Each April the team warmed up for the league schedule by playing various Chicago semipro teams. The regular season opened in 1916 against the Indiana Hoosiers, who captured a closely fought 4-3 win. The game was indicative of the season as the Northwesterners were unable to outscore their opponents. They closed with a 1-8 record in collegiate competition. Their lone victory came against Chicago in early May. Driscoll opened the game with a long triple to center field, then played flawlessly at shortstop. His Purple won 10-6 thanks to a late rally.7

The next season, 1917, Northwestern opened with a 3-0 win at Purdue. Arguably Driscoll’s best game came on April 25 at Chicago. Forced to pitch because of the illness of Northwestern’s best hurler, Driscoll turned in a fine performance and added a two-run triple in a 6-2 victory.8 In a rematch a few days later, Driscoll, playing shortstop and batting cleanup, delivered three hits, including a double, in the 9-4 Purple win.9 Northwestern finished the league season at 4-4.

When the college season concluded, Driscoll began working out with the Chicago Cubs. On June 12 the Cubs were entertaining the New York Giants. In the sixth inning, Cubs captain and second baseman Larry Doyle got into an argument with umpire Bill Klem over whether a ball had gone out of play. Klem prevailed and ousted the overly exuberant Doyle from the game. Driscoll took Doyle’s place.10 He doubled off Jeff Tesreau in the seventh in his first major-league at-bat in a game the Giants won, 10-6.

Driscoll’s debut created a bit of controversy. League President John Tener in a telegram to Charles Weeghman, president of the Cubs, informed him that the use of Driscoll violated the 22-man roster rule. The Cubs’ defense was that they believed the roster limitation applied only to players under contract.11 Driscoll was being auditioned without any formal agreement, not uncommon in those days.

Driscoll’s debut created a bit of controversy. League President John Tener in a telegram to Charles Weeghman, president of the Cubs, informed him that the use of Driscoll violated the 22-man roster rule. The Cubs’ defense was that they believed the roster limitation applied only to players under contract.11 Driscoll was being auditioned without any formal agreement, not uncommon in those days.

The Cubs released Vic Saier, paving the way for Driscoll to see additional action.12 Doyle sprained an ankle on July 2, allowing Driscoll to play the next five games. He went 2-for-19 and committed four errors. Although he was a gifted athlete, it was obvious that he was overmatched on a major-league diamond. He made only five more appearances that season; going hitless to close out the season and his big-league career with a .107 average.

Driscoll did not play collegiate football in 1917 or after. Various stories in late 1916 suggested that he was academically ineligible, but those proved inaccurate since he played college baseball in the spring of 1917. Other reports suggesting that he had joined the military were erroneous; he did not enter the service until 1918.13

Driscoll had forsaken the college game for the professional ranks and was playing with the Hammond Pros, earning $50 a game. On October 14 he scored the only touchdown of the game and kicked a 40-yard field goal in a 9-3 Hammond win over Davenport, Iowa.14 He closed out the season with a 55-yard dropkick and a touchdown run from his quarterback spot in a November 12 win.15

On March 7, 1918, Driscoll enlisted in the US Navy at the Great Lakes Naval Station, outside Chicago.16 He was joined at the Naval Station by George Halas, Red Faber, and a host of other talented athletes. Great Lakes sponsored a baseball team that played in the spring and summer. The culmination of their season was a benefit game staged August 5 against the Atlantic Fleet team, led by Rabbit Maranville.

In that game Driscoll played shortstop and batted cleanup. He had four singles and a double before flying out in his final at-bat. Faber entered the game in relief and struck out seven to help Great Lakes win, 11-6. The win made the Naval Station the champion of the East and Midwest. On the West Coast, the base at Mare Island (Vallejo, California) fielded a team with nine former major leaguers and claimed the Western title.17 A crowd of 7,000 watched the game with proceeds going to the Naval Relief Fund.

Soon after the charity game, both Driscoll and Halas left the baseball team to concentrate on their studies to earn commissions as ensigns.18 A few weeks later, football practice began with Driscoll and Halas ready for action. Because of an injury, Driscoll played quarterback when the season opened against the Iowa Hawkeyes. He guided a potent running game and scored a 35-yard dropkick in the 10-0 victory.19

When the regular quarterback returned from injury, Driscoll switched to halfback. He also handled the punting and dropkicking. The team beat the University of Illinois 7-0 on a touchdown pass to Halas,20 and played a scoreless tie with Northwestern on a “slippery, soggy field” when Driscoll missed two dropkicks.21 A 7-7 tie with Notre Dame followed. The team then journeyed east for games against Rutgers and the Naval Academy. Driscoll was returned to quarterback for those two games.22

Great Lakes was down 14-13 at halftime vs. Rutgers but with Driscoll “running wild” in the second half, the sailors scored 40 points for the win.23 But the match with the Naval Academy was not Driscoll’s finest day. While his Bluejackets won, 7-6, his four missed dropkicks made for a frustrating afternoon.24 Returning home, Great Lakes defeated Purdue 27-0. This set up a showdown with the Mare Island Marine eleven in the Rose Bowl on New Year’s Day 1919.

The contest between sailors and marines was staged at Tournament Park in Pasadena, where the Chicago Cubs held spring training. A crowd of 25,000 saw Great Lakes take the lead on Driscoll’s dropkick. The sailors added a touchdown in the second quarter to lead 10-0. They closed out the scoring in the second half on a Driscoll-to-Halas 22-yard touchdown pass for the 17-0 win.25

Columnist Walter Camp released his College All-American team for 1918 and stirred debate around the country by ignoring the service teams like Great Lakes. A week later he released his All-Service selections, which had Driscoll at quarterback on the first team and Halas as a second-team end.26

In mid-March of 1919 Driscoll and Halas were both released from military service. Driscoll boarded the train in Chicago on March 20 for Cubs spring training in Pasadena. There had been months of speculation concerning his release to a West Coast team. Soon after reaching California, he was sent to the Los Angeles Angels’ camp. He opened the season at shortstop in the Angels’ 13-inning win over Portland.27

The Angels burst out of the gate and were 10-1 after two weeks. Driscoll showed good glovework but was inconsistent at the plate. The team’s start was surprising since it had a youngster at short, a second baseman (manager Red Killefer) with a weak arm, and a third baseman battling injury, Duke Kenworthy, who was much better at second base. Despite the “makeshift infield,” the team had “other clubs shouting for help.”28

Driscoll had his finest day with the bat on April 20 in a doubleheader against the Vernon Tigers in Los Angeles. In the morning he had three hits, including a double, and scored thrice. In the afternoon he went 2-for-4 with a double and scored twice. On April 25 he homered in a 7-1 win over Salt Lake City. Good days like those would be followed by a string of three or four hitless outings. Driscoll’s fielding was equally inconsistent; he made 20 errors in 38 games. He lost his spot to Fred Haney, who in turn was replaced by Bunny Fabrique. The Angels lost the pennant to Vernon despite 108 wins. (They lost 72 games in the PCL’s elongated season.)

Driscoll served a utility role for a week or two before he was released in late May. A week later he was back in Chicago and playing shortstop for the semipro Gunthers. His professional baseball days were over, but he would play in Chicago leagues until he was in his late 30s.

In the fall Driscoll assisted at Northwestern and then played with Hammond again. His most noteworthy game came late in the season against Jim Thorpe and the Canton Bulldogs, which Canton won 7-0. The only score came after a host of Bulldogs tacklers jarred the ball loose from Driscoll on a kick return to set up a short scoring drive.29

Professional football as we know it began in 1920 with the formation of the American Professional Football Association. It changed the name to the National Football League two years later. From 1920 through the 1925 season, Driscoll played quarterback and halfback for the Chicago Cardinals, a charter member of the APFA. He was the head coach the first three seasons of that run. He was selected to the first-team All-Pro squad in four of his six years with the Cardinals.

At the height of his career, Driscoll’s name seemed to be everywhere. There was a syndicated newspaper column in which Driscoll explained the intricacies of football. He was a frequent guest and speaker at luncheons and sports gatherings in the Chicago area. His name also appeared in advertisements for Sears Roebuck Sporting Goods. He was listed with Grover Cleveland Alexander, Red Grange, and others in their praise of the gear available.

Some of Driscoll’s highlights on the field included scoring four touchdowns and adding three extra points in a 60-0 rout of the Rochester Jeffersons on October 7, 1923. He twice dropkicked goals from 50 yards or more. Driscoll held the league record for the longest field goal until the 1950s. In 1925 he made four dropkicks in a game, helping the Cardinals to the title with an 11-2-1 record.

Driscoll’s most talked-about game came on Thanksgiving Day (November 26), 1925. Collegiate sensation Red Grange had left the University of Illinois and signed with the Chicago Bears. He made his debut on the holiday against the Cardinals in front of a crowd of 36,000.30

Grange was a slashing runner but was perhaps more dangerous as a kick returner. It was not unusual for there to be 15 or more punts in a game, adding to the threat posed by a good return man. Driscoll handled the punting duties for the Cardinals. The plan was to always kick away from Grange. Using a baseball analogy, Driscoll said, “Punting to Grange is like grooving a pitch to Babe Ruth.”31 Driscoll punted over 20 times in the game and only three punts were fielded by Grange, who returned them for a total of 56 yards. The game ended in a 0-0 tie. Driscoll was booed heartily by the crowd for his punt placement. The fans yearned to see Grange’s open-field skills, but Paddy was a smart, tough competitor and stuck with the game plan.32

In the offseason Driscoll was sold to the Bears for $3,500 and was reunited with George Halas, the team’s player-coach.33 Driscoll won All-Pro honors in 1926 and 1927 playing halfback for the Bears, who finished second in 1926, then third in 1927. Paddy led the team in scoring each season.

The Bears faltered the next few seasons and an aging Driscoll saw less playing time. In 1929 the Grange brothers (Red and Garland) were brought in to play halfback and Driscoll saw the end approaching rapidly. Since 1924 he had been coaching football and basketball at St. Mel High School (named for a fifth-century Irish saint and nephew of St. Patrick) in Chicago. His duties went to full-time employment in 1930 when he became athletic director.34

Loyola University in Chicago sponsored the National Catholic Prep Basketball Tourney each winter. Catholic high schools from all over the Eastern United States were invited to showcase their talents. Over the years, Driscoll’s teams from St. Mel won the tourney twice and had a runner-up finish.35

In 1936 he became an assistant to Halas again with the Bears. They placed second in the NFL West Division behind the eventual champion Green Bay Packers. Paddy took the head coaching job at Marquette University the following year and stayed there through the 1940 season before returning to the Bears. He could muster only 10 wins at Marquette.

Driscoll served as Halas’s assistant for 15 seasons before taking over the head coaching duties in 1956. He guided that team into the championship game with a 9-2-1 record. The New York Giants routed the Bears, 47-7, on a slippery, icy field. The following year the Bears finished in fifth place.

Halas returned to the sidelines in 1958 and Driscoll went into the front office. He was eventually named a vice president of the Bears. In 1963 he was placed in charge of research and planning, putting his expertise to use in breaking down film and creating scouting charts.36

Being a professional athlete and coach certainly put Driscoll in the spotlight, and he handled the notoriety well. He managed to keep his public life separate from his private life, which for the most part was shielded from public view.

One of the few exceptions came when Driscoll’s engagement to Mary Loretta McCarthy became known in January 1928. Papers across the nation carried the news, including a bold headline in the home of the rival Green Bay Packers. His June wedding even was captured by Chicago Tribune photographers.37

Married on June 2, he and Mary spent a three-week honeymoon in Montreal and New York City. They made their home in Chicago after that. In 1932 they welcomed their only child, John Jr. The younger Driscoll would eventually earn a master’s degree in business administration and work in the steel industry. He married and the family would add two grandchildren to the Driscoll clan. After a lengthy illness, Mary Driscoll died on January 16, 1960. She was buried in All Saints Cemetery in suburban Des Plaines.

Paddy Driscoll was plagued by a leg ailment, one of the reasons he had been moved to the front office. In June 1968 he was hospitalized for treatment at the Illinois Masonic Hospital. He alerted friends and family that he was scheduled for release but suddenly took a turn for the worse and died on June 29. Halas had visited with him just hours before the death. Approached by reporters, Halas said, “He (Driscoll) was anxious and happy to get back home. Now he’s gone. … It’s a terrible shock. … He was the greatest athlete I ever knew.”38

Besides the family of John Jr., Driscoll was survived by two sisters and a brother. Like Mary before him, he was buried in All Saints Cemetery. George Halas was an honorary pallbearer for his friend of 50 years.

Driscoll was highly praised for his talents. His college football coach, Fred Murphy, said, “Driscoll is without a doubt the greatest football player I ever saw.”39 Paddy was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1965, the College Football Hall of Fame in 1974, and the Northwestern University Athletic Hall of Fame in 1985. His style and intensity were epitomized by writer Walter Eckersall, who said, “Driscoll was among the first to use the pivot in dodging, he ran with his knees kicking nearly as high as his chest.”40 Eckersall further noted that Driscoll was an excellent blocker, unafraid to pave the way for a teammate.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and Bill Lamb and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Notes

1 Northwestern University did not adopt the Wildcats nickname until the 1920s. When Driscoll was a student, its teams were referred to as the “Purple.”

2 “Four Ex-Bears Gain Pro Hall,” Chicago Daily News, September 13, 1965: 18.

3 The University of Michigan re-entered in 1917 to make it a 10-team league, paving the way for the name Big Ten. athlonsports.com/college-football/complete-history-big-ten-realignment. Last accessed February 6, 2020. The league was also known as the Western Conference.

4 “Purple Team Ready for Game Tomorrow,” Daily Northwestern (Evanston, Illinois), October 6, 1916: 1. The Northwestern Media Guide lists A.H. Henry as the captain, but numerous contemporary newspaper articles state the case for Driscoll as captain. He was re-elected for 1917 but did not serve.

5 “Purple Beats Maroons, 10-0,” Daily Northwestern, October 24, 1916: 1.

6 “Purple Beats Maroons.“

7 “Maroon Nine Routed in the Eighth Inning,” Daily Northwestern, May 3, 1916: 1, 4.

8 “Purple Beat Chicago by Timely Hitting,” Daily Northwestern, April 27, 1917: 1, 2.

9 “Purple Nine Outclasses Maroons by Air-Tight Pitching and Fielding,” Daily Northwestern, May 2, 1917: 1.

10 “Giants Rout 3 Cub Hurlers in Batfest,” Chicago Daily News, June 12, 1917: 1.

11 “Cubs Cannot Keep Driscoll on Club,” Rock Island (Illinois) Argus, June 15, 1917: 19.

12 “Vic Saier Is Released,” Moline (Illinois) Dispatch, June 22, 1917: 14.

13 “Big Ten Starts Football Work,” Daily Illinois State Register (Springfield), September 16, 1917: 20.

14 “Hammond Beats Davenport, 9-3. Driscoll Stars,” Rock Island Argus, October 15, 1917: 11.

15 “Hammond Defeats Hamburgs, 13-3,” Rock Island Argus, November 12, 1917: 11.

16 “Driscoll Enters Navy,” Daily Illinois State Register, March 8, 1918: 9.

17 John Alcock, “Atlantic Nine Beaten, 11-6 at Cubs Park,” Chicago Tribune, August 6, 1918: 14.

18 “Great Lakes Loses Two Diamond Stars,” Moline Dispatch, August 16, 1918: 9.

19 “Hawkeye Eleven Drops Fracas to Great Lakes,” Moline Dispatch, September 30, 1918: 10.

20 “Illini Fall Before the Attack of the Great Lakes Bluejackets,” Chicago Tribune, October 13, 1918: 21.

21 “Sailors Witness Scoreless Game,” Decatur (Illinois) Herald, October 27, 1918: 8.

22 Walter Eckersall, “Great Lakes Leaves Today on Football Invasion of East,” Chicago Tribune, November 14, 1918: 14.

23 “Illini Claim Title,” Moline Dispatch, November 18, 1918: 10.

24 “Great Lakes ‘Gobs’ Defeat Middie Team,” Los Angeles Evening Express, November 24, 1918: 10.

25 “Great Lakes Win Big Football Game,” Chicago Daily News, January 2, 1919: 2.

26 “West Lands One Berth on Camps Service Eleven,” Denver Post, January 8, 1919: 12.

27 “Angels in 13 Frames Defeat Portland Beavers,” Seattle Daily Times, April 9, 1919: 18.

28 W.A. Reeve, “And With a Makeshift Infield,” Los Angeles Evening Express, May 1, 1919: 21.

29 “Edwards Covers Fumble, Bulldogs Run Off Three Plays and Win Game 7-0,” Canton (Ohio) Repository, November 28, 1919: 32.

30 Irving Vaughan, “Grange Gains 92 Yards for His Pro Debut,” Chicago Tribune, November 27, 1925: 21. Football Reference puts the attendance at 39,000.

31 Will Larkin, “Ranking the 100 Best Bears Players Ever: Number 34, Paddy Driscoll,” Chicago Tribune, August 3, 2019. chicagotribune.com/sports/bears/history/ct-spt-bears-best-players-paddy-driscoll-20190803-ncqdrx6cofejtmdxuj7yxracgm-story.html. Accessed February 10, 2020.

32 Larkin. Driscoll’s punt total was reported as 23 by some, 25 by others.

33 Edward Prell, “Speak of the Card-Bears Series and You Talk of Driscoll,” Chicago Tribune, November 29, 1945: 28. Grange formed his own team in 1926 so Halas really needed a halfback like Driscoll to fill that void.

34 Edward Prell, “Driscoll Tells Bears What to Do, but Not What He Did,” Chicago Tribune, July 11, 1944: 15.

35 “Varnes’ St. Pat’s Cagers Win National Prep Crown,” Kenosha (Wisconsin) Evening News, March 21, 1932: 10.

36 “Chicago Sports Figure for More Than 50 Years,” Chicago Tribune, June 29, 1968: 53.

37 Chicago Tribune, June 3, 1928: 31.

38 “Chicago Sports Figure.”

39 “Chicago Sports Figure.”: 54.

40 Walter Eckersall, “Paddy Driscoll Purple’s Best in the Last 20 Years,” Chicago Tribune, November 10, 1925: 29.

Full Name

John Leo Driscoll

Born

January 11, 1895 at Evanston, IL (USA)

Died

June 28, 1968 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.