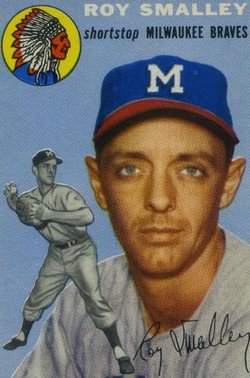

Roy Smalley Jr.

Roy Smalley Jr.’s six-season career with the colorful but awful Chicago Cubs after World War II ended when a rookie named Ernie Banks took his job. Smalley would forever known as the player Banks replaced.

Roy Smalley Jr.’s six-season career with the colorful but awful Chicago Cubs after World War II ended when a rookie named Ernie Banks took his job. Smalley would forever known as the player Banks replaced.

Smalley also is noted for being the father of a major-league player who had a better career, and a brother-in-law who was a longtime manager of the Minnesota Twins, Philadelphia Phillies, Montreal Expos, and California Angels.

Moreover, the lanky shortstop also suffered under the abuse of Cubs fans who booed him unmercifully for his dozens of errors, many on errant throws to first base. His wild throws earned him the wrath of fans with the chant “Miksis to Smalley to Addison Street,” a street running outside Wrigley Field. The words were a play on the famous Cub infield of Tinkers to Evers to Chance.1

Chicago newspaper columnist Mike Royko wrote that Smalley was a legend “because he could snatch up ground balls and fling them at the sun.”2 Years later in an old-timer’s game at Wrigley Field, Smalley still heard a smattering of boos.

His career can best be summed up by the 1950 season statistics that were the best and worst of his times.

Smalley was born on June 9, 1926, in Springfield, Missouri, and grew up watching the St. Louis Cardinals’ Class C farm team there, which piqued his interest in playing baseball. He was signed by the Cubs in 1944 when he was 17 and was assigned to the Pacific Coast League’s Los Angeles Angels, where he batted .188 in 61 games. He had an early penchant for errors, committing 23 in 55 games.

Then Smalley served 22 months in the Navy during the war, and played for a base team managed by Ernie Koy, a speedy outfielder once with the Brooklyn Dodgers, among other teams.

When Smalley returned to baseball in 1946, he split his time among Shelby, North Carolina, in the Class B Tri-State League, Davenport, Iowa, in the Class B Indiana-Illinois-Iowa League, and the Angels again, where he batted an accumulative .210 in 41 games. The next year he suited up for the Des Moines Bruins of the Class A Western League, where he hit .244 in 114 games.

The Cubs called Smalley up in 1948, despite his mediocre statistics, and he held down the shortstop position for six seasons. In his rookie year Smalley weighed 190 pounds on his 6-foot-3-inch frame, tall for a shortstop in those days. He was about 5 inches taller and 20 pounds heavier than the typical shortstop of his era. For example, Gene Mauch, his future brother-in-law, who played shortstop for the Boston Braves at the same time, was 5-feet-10 and 165 pounds. Smalley had average speed but was quick and had a good range with a powerful arm.3

In his rookie year, Smalley played in 124 games and batted .216 with 34 errors in 574 fielding chances for a .941 average for the last-place Cubs, who finished 60-94. But Smalley’s future was promising, to hear other players’ and managers’ opinions.

Just before the 1949 season began, New York Giants manager Leo Durocher remarked, “He certainly has come a long way in a short time. He could be great before the season’s over.” Smalley’s manager, Charlie Grimm, retorted, “Whatta ya mean, he could be great? He’s the best in the National League right now.” Emil Verban, who played with Cardinals shortstop Marty Marion, said Smalley had “the greatest arm I’ve ever seen in baseball.” Tris Speaker , a part-time coach with the Cleveland Indians, called him “a natural acrobat” who would soon be playing in the All-Star Game.4

Smalley had spent the offseason working on his batting with two Cubs pitchers on Catalina Island, off the coast of California, where Cubs owner William Wrigley had a mansion. While there, Smalley helped take care of Wrigley’s prized Arabian horses.5

Despite all the accolades, Smalley didn’t improve much in 1949, when he hit .245 in 135 games. Neither did the Cubs, who won 61 games and lost 93. But in 1950 Smalley set all kinds of personal bests – and worsts for that matter. He hit two triples and a homer off standout Johnny Sain in one game and hit for the cycle in another. His bat showed some pop as he belted 21 home runs and batted in 85 runs. On the downside, he struck out a league-leading 114 times.

With the glove, Smalley led all National League players with 51 errors. (He had topped the league in errors the previous two years as well, with 34 and 39.) On the other hand, he led the league in assists with 541, putouts with 332, and double plays with 115, six of which came in one game. Those statistics earned Smalley a pay raise from $10,000 a year to $15,000 for 1951, the most he would earn in one season in his career. The Cubs’ record? They moved up to seventh place with a 64-89 record.

That season Smalley married Jolene Mauch, sister of Gene Mauch, in Brookline, Mass., while the Cubs were playing the Braves on August 5. Later in the day Smalley went 0-for-5 against his new brother-in-law and the Braves. Two years later, future All-Star infielder Roy Smalley III was born and would later play for his uncle Gene in Minnesota.

Jolene attended many of Chicago’s games, rooting for her husband. But often before the game was over the raspberries that rained down on her husband brought her to tears. Years later, when the Smalleys’ son was going through some tough times in the minor leagues, Roy Jr. told him, “It could be worse. You should have heard them boo me in Chicago.”6

Ira Berkow, who went on to become a Pulitzer Prize-winning sportswriter for the New York Times, remembered watching Smalley in Chicago, his hometown. “What I remember most about (him) was the abuse he endured,” Berkow said 25 years later.7

Smalley said he tried not to let the boos bother him. “Most of the time I didn’t hear the boos on the field,” he said. “It was only afterward that I would think about it. I think a ballplayer if he is going to make it doesn’t react as negatively to bad things as he does to positive ones. You steel yourself to maintain your confidence and spirits of spite of everything.”8

A year later, not long into the season, April 28 to be exact, during a winning game against the St. Louis Cardinals, Smalley was heading for third base when manager Frankie Frisch, who was in the third-base box, signaled him to slide. As he started to slide, Frisch changed the signal to stand up. Smalley rolled his ankle and broke a small bone in his left leg that kept him out of the lineup for more than four weeks. (In his 80s, Smalley’s ankle still bothered him, causing a slight limp.)9

He played in only 79 games that year. Never again in his big-league career did Smalley play more than 92 games. Whether that was a result of his injury or his record on the field is unclear.

Toward the end of the 1953 season, the future “Mr. Cub” Ernie Banks started the last ten games of the season in Smalley’s place. The 22-year-old Banks hit .314 and had a .981 fielding average in that brief period and he was on his way to a Hall of Fame career. Smalley was no longer in the Cubs’ plans. The next spring he was traded to the Milwaukee Braves for pitcher Dave Cole and $50,000. Smalley could see it coming. “I felt that a trade was in the cards,” he said. “I do feel strange at leaving the Cubs after six years, but it’s a wonderful break.”10

Smalley was reunited with Charlie Grimm, who had managed him his first two years with the Cubs. “When I first saw him I figured he couldn’t miss,” Grimm said at the time of the trade. “I still believe he has possibilities.” Grimm planned to use Smalley as a backup.11

Teammates were saddened to see the popular Smalley leave. But they agreed that he needed to get away from the boo birds in Chicago. “Smalley was a fine competitor on the road,” said Bill Serena, who played in the infield with him, “but when he got back to Wrigley Field he was a different player.” Serena said Smalley never complained. Said another Cub, “When he went out on the field, all eyes were on Roy. … (The fans) came out to have a Roman holiday with Smalley. He played under a brutal handicap.”12

Twenty years later Smalley remarked about his days on the Cubs, “Sure, it’s not pleasant to be unpopular and have it demonstrated. But that’s where I wanted to be, the major leagues. …”13

Smalley’s stay in Milwaukee lasted just 25 games, during which he played shortstop, second base, and first base. On April 30, 1955, the Philadelphia Phillies purchased Smalley in a cash deal. He played for the Phillies until May 20, 1958, when he was released. As a free agent Smalley signed with the Cardinals, who assigned him to Rochester in the Triple-A International League. After that he played Minneapolis, Houston, Spokane, and Reno, where he also tried pitching without much luck. In Minneapolis he played for his brother-in-law Gene Mauch.

Smalley never made it back to the major leagues. For his 11-year career, he batted .227, hit 61 home runs, and knocked in 305 runs. On the field he made 207 errors for a .948 fielding average.

Smalley managed the Reno Silver Sox for two seasons. In 1961 his team finished first in the California League with a record of 97 wins and 43 losses. The next year the Silver Sox were 70-68 and he was fired. He left baseball and opened a janitorial service in Los Angeles, his wife’s hometown.

When Smalley’s son was a boy, Dad and son would play ball “but only because he liked it,” his father said. The elder Smalley never pushed the game on his son. “I’d talk to him about baseball, but I tried to restrain myself,” he said.14

Once son Roy began to make a name for himself, a confusion in their names arose. The father was Roy Jr. and the son Roy III. Often sportswriters would refer to the father as Roy Sr. and the son as Roy Jr.

Roy III starred at the University of Southern California and went on to sign a $100,000 bonus contract with the Texas Rangers. When he was struggling with the rigors of baseball, he would call home to talk with his father. Roy Jr. would counsel him as did his uncle Gene. Smalley remembered that during his son’s high-school and college days Jolene, young Roy’s mother, “thought Roy (III) felt too much pressure, how after a bad baseball day he’d come home so mopey. She got scared. But finally she thought that just the fact I was once a major-league player – just the presence of it – put the pressure on.”15

Roy III went on to play 13 seasons for the Texas Rangers, Minnesota Twins, New York Yankees, and Chicago White Sox, finishing with a career batting average of .257 and 217 errors, 10 more than his father but a fielding percentage of .965. He made the American League All-Star team in 1978.

Roy Jr. retired in 2004 to Sahuarita, Arizona, 30 miles south of Tucson, where he played golf with the same ardor as he did baseball. He died on October 22, 2011, at the age of 85.

-

Related link: Roy Smalley Jr. was the keynote speaker at SABR’s 10th annual convention in Los Angeles in 1980

Notes

1 Baseball-Reference.com.

2 Baseball-Reference.com.

4 Chicago Daily Tribune, March 28, 1949.

5 Green Valley (Arizona), News, July 1, 2011.

6 Ira Berkow, NEA sports editor, May 6, 1975.

7 Ira Berkow, May 6, 1975.

8 Ira Berkow, May 6, 1975.

9 Conversation with author in 2009.

10 Chicago Daily Tribune, March 23, 1954.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Ira Berkow, May 6, 1975.

14 Ira Berkow, May 6, 1975.

15 Ira Berkow, May 6, 1975.

Full Name

Roy Frederick Smalley

Born

June 9, 1926 at Springfield, MO (USA)

Died

October 22, 2011 at Sahuarita, AZ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.