Tim Thompson

At age 96 in 2020, Tim Thompson was one of the ever-rarer surviving veterans of World War II who played major-league baseball. Thompson also remained together with his wife of 77 years, Lois (two months younger). Their marriage outlasted Tim’s remarkable career in the game as player, manager, coach, and scout.

At age 96 in 2020, Tim Thompson was one of the ever-rarer surviving veterans of World War II who played major-league baseball. Thompson also remained together with his wife of 77 years, Lois (two months younger). Their marriage outlasted Tim’s remarkable career in the game as player, manager, coach, and scout.

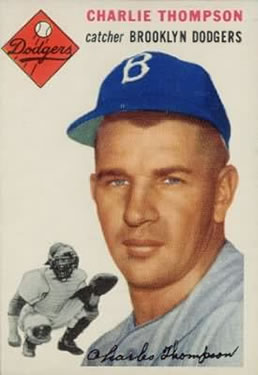

Thompson’s WWII service actually predated his time in the pros. He entered the United States Navy in May 1943 and separated from the service in December 1945. He signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1946 and began in the minors the following year. The catcher (said to be one of the first backstops to wear eyeglasses) finally made his big-league debut for the Dodgers at the age of 30, on April 20, 1954. He made his last appearance in the majors in 1958 and played on the minors through 1962. After his playing days were over, he came home to the place where his love of baseball began and enjoyed a long career in scouting.

Charles Lemoine Thompson — who became known as “Tim” — hailed from Pennsylvania, He was born in Coalport on March 1, 1924. “I don’t think I was there more than a month,” he said. His father, Maurice “Tommy” Thompson, and his mother Dorothy had one other child three years later: Dorothy Jean, known as “Shin.” The family moved around. They went to Lewistown for a while, then to Williamsburg when he was 4 or 5 years old. “My dad was pitching for Williamsburg. We went from there to Altoona, and then back to Williamsburg, back to Lewistown, and then we went to Spangler when I was a sophomore in high school.”1

His father earned much of his living playing baseball, while working a number of other jobs. At the time of the 1920 census Maurice was 18 and employed as a stamper in a steel mill. Maurice’s father Wynnfield had been a gardener working on a private estate. In 1930, Maurice was listed as a laborer for the electric light company in Williamsburg; in 1940 he was listed as a coal mine laborer in Spangler — but all of these jobs tied back to baseball.

Spangler was “a coal mining town up in the mountains, in the heart of the coal area,” but Maurice Thompson was never a coal miner. As Tim told historian Anne R. Keene, “My father was a ball player. Years ago, the coal mines all had baseball teams. Different mines would bring in people to help them build their team. When he didn’t pitch, he played the outfield. They paid him big bonuses for every game he won as a pitcher. And they’d give him a job, too. He didn’t do anything but just walk around and put in his time. He never did work in the coal mines. They played all over in Blair County. All the little towns had teams. One year he worked for the electric company in Altoona and pitched there.”2

So Tim had a bit of a baseball pedigree, though his father had turned to semipro ball after his birth. A Kansas City Athletics publication from 1957 reports that Tommy Thompson was once a member of the St. Louis Cardinals organization, but it appears his career was sidelined early on. “He was ready to go south one spring when Tim was born and that birth caused the new father to abandon his baseball career.”3

From at least 1942 on, Tim once again lived in Lewistown, the county seat of Mifflin County, and northwest of Harrisburg on the road to State College. “When they built the American Viscose plant in Lewistown, they were hiring people so Dad came there and became a guard.”

As an adolescent, he joined his father on the field, “I played with my dad on the coal mine teams. I was a shortstop. Augie Donatelli played third base. He was a great National League umpire. Augie’s from Bakerton, Pennsylvania, and that was this little mining town and they had a team. I played with them. I was just a teenager, 16 years old.”4

When Tim was 17, the United States entered World War II. He quit high school and got married, “I met my wife in high school. I came from Spangler. School was out there a couple of weeks before the one in Lewistown. Dad knew the baseball coach at Lewistown High School. I was a high school student, so I went over there and played two weeks for the high school team. I was a junior then and my wife was a senior. Lois Eileen McCarthy. She was a cheerleader. I played one year of football at that high school. She was cheerleading and I was running the football and run into her and knocked her down and that’s how I met her. We started going together and we ended up getting married at the end of that summer.”5

He then went into military service, joining the Navy on May 30, 1943. “I got drafted and went to boot camp in New York. Came out of there and went home for a week or so and they sent me to the Vallejo, California departure center for about a month. Finally, my name came up on the board and I was to go to Moffett Field in California.”6

Thompson’s duties in the Navy were two-fold. His primary assignment was to work aboard lighter-than-air craft — blimps. It wasn’t that he had chosen blimps as a specialty. Each airship had an eight- to 10-man crew and he was assigned to one.

“I went to school to learn how to fly them. We had our own hangar in a different part of Moffett Field. I was on a crew. Every fourth day, we had 18 hours on one of them. We’d go to the San Francisco bridge and we’d pick up a warship, or two or three ships [and escort them] until we’d get out about 100 or 200 miles. Out on the horizon, you would see three or four hundred ships. We had radar on that blimp and all we did was glide back and forth across the water with all the convoys in case there was any submarines

“That’s what I did. I learned how to pilot one of them. We had an hour’s work for each one of us. We’d change shifts every hour. Had to do the radio, had to do the piloting…we had to do it all.”7

The blimps were also armed with a 50-caliber machine gun, mounted behind where the pilot and co-pilot were. “We never ran into any [submarines] when they were above water. We didn’t have any problem with that on the West Coast. On the East Coast, they did have some submarines surface and they had to blast them. But we didn’t have any problems.”8

When he wasn’t airborne, Thompson worked in the athletics department for general conditioning and morale, and also to rehab returning servicemen. After his flying shifts, he’d have three days helping to organize athletics programs on the base. He particularly remembers working with Marines who had fought at Guadalcanal. “I had the boxing team. I had the baseball team. I organized the football team. I was in charge of the WAVEs, to give them their phys ed and all that. We played some of the high schools, like in San José. I did all that and I played some baseball.”9

He played against a lot of former professional ballplayers while in the Navy, but Thompson wasn’t someone who had followed the pro game. “The Fresno Army team was the winner of the 12th Division, all the service teams in California. Fresno was all professional baseball players. Double A, Triple A, major leagues, I don’t know. At that time, I didn’t know one ballplayer from another. I didn’t think that much about major-league baseball. At that time, I couldn’t tell you who Babe Ruth had played for. They didn’t interest me. If I couldn’t be in the field playing, I didn’t care who was there.”10

Thompson was discharged from the Navy at Camp Parks, California, on December 14, 1945 as a Seaman First Class, “because if I’d got any higher, they’d have sent me out of there. I stayed right there at Moffett Field until I was discharged. The captain said, ‘Tim, if you would leave here, I don’t know where they would send you. As long as you’re First Class, I can keep you here.’”11

Thompson made his way home in time for Christmas. He took a job at the American Viscose Company factory, working on the manufacturing line at a coke factory where they made yarn for tires.

That’s when he got a call from Bill Killefer, working as a scout for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Rex Bowen, a scout from the Pittsburgh Pirates, had seen Thompson play while in the service, and he mentioned Thompson to Killefer. Thompson told Killefer that he’d be playing at a park on Sunday with an all-star team from Mifflin County. Before the game, Killefer talked to the umpire, Charlie Curry. “The umpire happened to be my grandfather. He asked my grandfather, ‘What does this boy play?’ My grandfather said, ‘Boy, that boy plays shortstop, pitches, catches, whatever you want him to do, he can do.’ Well, I played shortstop three innings, I pitched three innings, and I caught three innings.” Thompson threw right-handed, but batted from the left side. He stood 5-foot-11 and was listed at 195 pounds.

According to Thompson, Killefer came back to his house and met with his mother and father. “He said, ‘I’m going to send you to Brooklyn tomorrow as a catcher.’ So my dad and I went to Brooklyn for three days. The Dodgers signed me then.

“While we were in New York, the Cardinals and the Dodgers were playing a three-game playoff in the National League that year at Ebbets Field. I went and caught batting practice for the Cardinals in the morning, then I caught batting practice for the Dodgers. I had to do some hitting for Andy High and Clyde Sukeforth. They watched me work out that whole day. The next day I went out and did the same thing.

“I signed with the Dodgers but when I got home, I had a telegram from the Philadelphia Phillies. It said, ‘Whatever the Dodgers offered you, we’ll top it.’ I said, ‘I’ve already signed, but thank you very much.

“That was in ’46. In ’47 I went to spring training.”12

While with the Dodgers, Thompson got to know the Rickeys. “I spent a lot of time with Mr. [Branch] Rickey and his wife. We were in spring training. The players all used to walk along with a tray to eat, to get your meal, like in the service. One time Mr. Rickey and his wife happened to be in line with me. We were moving along and talking. She asked me, ‘Do you like it here?’ I said, ‘I love it.” She asked, ‘How is the food?’ I said, ‘The food’s outstanding. It’s great.” She turned to him and said, ‘Did you hear that? This boy said the food’s good, but they don’t give you enough to eat. But it’s good.’ He said, ‘Is that right?’ He handed me one of his name cards. He said, ‘You keep that card and if you want to get something to eat, you go to the kitchen and ask for the cook. Make sure you give it to him. Show him this card. I want you to have enough to eat.’ He wrote something on the back of the card.

“He spent a lot of time with the Brooklyn Dodger pitchers, and I was a catcher so he stood behind me when the pitcher was throwing. Later on, with Koufax and Erskine and all those guys.

“They sent Sandy to Puerto Rico with me one year because they wanted Sandy to learn how to throw a breaking ball. He had a great arm but couldn’t throw a breaking ball. Sandy and I became very good friends.”13

“Mr. Rickey used to move me around a lot. Elmira, then Montreal for a couple of weeks, and then to St. Paul.”

In 1947, Thompson played for the Cambridge (Maryland) Dodgers of the Class-D Eastern Shore League, appearing in 114 games and hitting for a .349 average. He tied for the league lead in base hits with 162 and was named the catcher on the league All-Star team. He had some speed; his 14 triples led the league. He was bumped up to Class B in 1948 and spent most of the year catching for the Piedmont League’s Newport News Dodgers, hitting .303 in 110 games. (He had three games in Triple A with St. Paul.)

Thompson’s 1949 was split between Newport News (26 games) and the Dodgers’ other Triple-A affiliate, Montreal. In 46 games for the Royals, he hit for a better average than at the lower level, .278 to .265.

However, the Dodgers organization had an abundance of catchers. All of them were stuck behind the great Roy Campanella, whose Hall of Fame prime was just beginning. Campy’s primary backups in Brooklyn were Bruce Edwards and later Rube Walker. Some catchers, such as Sam Calderone, didn’t get their chance in the majors until they left the Dodgers system, which Arch Murray of the New York Post likened to a chain gang.14

Thompson played most of 1950 for the Eastern League’s Elmira Pioneers (Class A, 92 games, .276), though he also appeared in 12 games for Montreal, taking advantage of the opportunity and going 14-for-30 (.467). Montreal’s primary catcher in 1950 was Toby Atwell, who (like Calderone) did not get his shot in the majors until he was out of the Dodgers organization.

The next three seasons, Thompson spent the whole year with just one club, all in Triple-A. In 1951, it was St. Paul (108 games, .296). In 1952 and 1953, he played for Montreal. He appeared in 115 games and hit .303 in ’52 and in 1953 it was 109 games and .293. Throughout, his batting averages were quite high for a catcher, by the standards of the day. In 1953, he hit 10 home runs, the first time he had reached double digits. His .991 fielding percentage led the league in 1952, just as he had led the league in fielding back in 1947.

Finally, at age 30, Thompson made the majors. He broke camp with Brooklyn. His debut came in the sixth game of the season, pinch-hitting in the top of the ninth inning, facing Murry Dickson of the Philadelphia Phillies. The Phils were up, 6-3. Thompson led off, but popped up a foul to the catcher.

His second game was on April 28 in St. Louis. He played left field in the 10th inning. It was, he said, “the only time I ever played in the outfield. It was in St. Louis. Dick Williams was ejected, and I was the only one left on the bench. Steve Bilko lined a single and I thought I nailed Dick Schofield at the plate with a good throw, but he slid between Roy Campanella’s legs to score. I kidded Campy that if he had blocked the plate I would have been a hero.”15

His first big-league base hit came in his third game, also against the Cardinals, on May 14. It was his second at-bat; once more it was the top of the ninth in a pinch-hitting role, with Brooklyn trailing, 10-1. He hit an infield single but was erased on a double play.

Thompson got his first starting assignment in the second game of the May 16 doubleheader at Ebbets Field as the Dodgers hosted the Reds. In the bottom of the ninth. Thompson doubled, driving in his first run. The game ended with the next batter.

He appeared in six more games in May. mainly as a pinch-hitter or pinch-runner. Overall, he was 2-for-13 with the one RBI. He spent the remainder of the season back in Montreal, where he hit .305.

Thompson was notable as the first catcher in the National League to wear eyeglasses. He had begun to wear them in 1952 when with Montreal. Clint Courtney was credited (with an element of doubt) as the first catcher in the majors to wear them (1951).16

In 1955, it was Triple A again, all year, for Thompson, once more with St. Paul. He hit over .300 for the fifth time (.313 in 121 games.)

He joined the Dodgers for spring training in 1956 but on April 16 was traded to the Kansas City Athletics for veteran outfielder Tom Saffell, right-handed pitcher Lee Wheat, and cash. For both Saffell and Wheat, their major-league days were behind them.

Thompson played the next two years in the majors for manager Lou Boudreau and the Athletics, sharing catching duties with Joe Ginsberg and Hal Smith in 1956 and with Smith in 1957. Thompson appeared in 92 games the first year, catching in 68 of them and pinch-hitting in the rest. He put together a .272 batting average (.319 on-base percentage), drove in 27 runs and scored 21. In the second game of the May 27 doubleheader in Detroit, he had his best day — 3-for-4 with a double and his first major-league home run, off Duke Maas in the second inning of a 5-0 K.C. win. It was his only home run of the year. On June 3, he singled in the top of the 10th inning of a game in Boston, driving in the go-ahead run to beat the Red Sox, 7-6. It capped two days in which he had reached base in nine of 11 plate appearances, going 6-for-8, and driving in four runs. By the end of June he was batting .327.

In 1957, he homered not once but seven times. His biggest day was July 1, kicked off by a three-run homer in the top of the first inning off Cleveland’s Early Wynn, helping to end an11-game Athletics losing streak. For the season, however, his batting average dropped considerably, to .204. He suffered through a horrendous slump of 12 games and 42 at-bats without a hit, finally breaking it with a game-winning RBI single on August 19 to beat Cleveland, 1-0.17 All told, he drove in 19 and scored 25.

After the season, Thompson was part of a 13-player trade with the Tigers. He caught in four April games for the Tigers in 1958 and had one base hit — his last in the majors — and three walks in nine plate appearances.

In total. Thompson appeared in 187 big-league games, hitting .238 with a .293 OBP. He drove in 47 runs and scored 49. His lifetime fielding percentage was .986 (10 errors in 696 chances.)

He still had five more years of baseball ahead of him, though — all with the Toronto Maple Leafs in the Triple-A International League. He almost didn’t go to Toronto, but once he did, he truly enjoyed his time there. He told an amusing story:

“John McHale called me in and said, ‘I just sold you to Toronto.’ Jack Tighe was the manager with Detroit. I’d just come back on a road trip with them. He told me, I told John McHale not to sell you, and to keep you.’ He said, ‘I want you to talk to [Toronto owner] Mr. [Jack Kent] Cooke and then go home and get something for yourself. Don’t go to Toronto.’ So, OK. I listened to Jack and I called Mr. Cooke and I said, ‘I’m sorry, I’m not coming.’ John McHale said, ‘I’m going to blackball you then. Go on up there.’ ‘No, I’m not going.’ [There were some calls back and forth.

“Finally, Mr. Cooke called me and said, ‘Tim, what kind of car do you drive?’ At that time I was driving a Chevrolet. I said, ‘I drive big cars. Big Buicks.’ He said, ‘You go down to the dealer. Pick out a car. Tell the owner to bill me for it.’ I went down and looked at the biggest Buick they had and said, ‘I’ll take that car there.’ So, I got a new car. That’s what I got out of the deal. I went to Toronto then. In fact, we lived up there. Two years, my wife and I did. We loved Canada.

“I said to Mr. Cooke, ‘How about letting me stay here this winter? Let me sell some tickets for you.’” Thompson said he structured a number of deals, partial ticket plans, and so forth, bringing back a lot of people to Maple Leafs baseball games, even bringing in $80,000 in one month from selling tickets. “And I sold billboards. Doing PR work for them.”18

Thompson was one of two managers for the Maple Leafs in 1961, taking over for Johnny Lipon during the season.

“Then I came back home in 1962. I started scouting for the Dodgers. Tom Lasorda, he was a scouting guy. Lived in Pennsylvania. Tom was going to go to California. He lived in Norristown. He said, ‘Tim, I want you to come down and spend some time together. I’m going to California. I want you to take the job scouting in my place.’”19

“He recommended me to take the scouting job in the Eastern part of the United States. That’s why I quit playing. That’s why I left the field.”20

“I worked a year for the Dodgers, but I spent the whole summer as a coach for their Single-A team. During the winter, Al] Campanis fired me. Rex Bowen was a very good friend of mine. He said, ‘Tim, I want you to come to Houston for the winter meetings. I want to introduce you to Bob Howsam.’ They offered me a job scouting which doubled my salary with the Dodgers. I became a scouting supervisor for the St. Louis Cardinals in the East. I spent 30 years scouting for the Cardinals. That’s who I retired from.”21 Thompson’s hiring was announced in January 1965.22

During his playing and scouting careers, he traveled to Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and Venezuela. He remembers walking to the mound with Venezuelan president Rómulo Betancourt for pre-game ceremonies and casually asking the president about the scars on his arm; he was told they were from a bombing (an assassination attempt). He stood a little farther from the president after learning that. Later on, Thompson managed there for a season. It was in Venezuela where he completed the paperwork that got him his high school diploma.

In Cuba before one game, played at 9 o’clock in front of about 3,000 Cuban soldiers, Fidel Castro helicoptered in and Thompson warmed up the Cuban leader in the bullpen. “Steve Ridzik was going to be our starting pitcher.” He was, Thompson said, very particular about his pre-game warmups. Castro’s arrival interfered with his preparation. “[Castro] threw about 15 minutes and then he walked back toward the helicopter and Steve Ridzik was mad because he’d cooled off from being warmed up so he threw the ball at Castro. Missed him, and hit the helicopter.” He recalls a lot of guns being pulled, “pointed right at us but Castro turned around and gave a big laugh and smile and took off.”23

Thompson did a lot of advance scouting, including of the Red Sox ahead of the 1967 World Series. A 1976 article showed him scouting the Yankees. During his years with the Cardinals, Thompson was credited with signing a number of players, including Tom Herr, Ricky Horton, Clay Kirby, Brian Jordan, and John Mabry, though much of his work (along with advance scouting) was as a supervisor. He spent his last 10 years with St. Louis in that role.

During the 1981 season, he is listed as serving the full season as a coach with the major-league team, but says he had actually only coached third base for a couple of weeks.24

Thompson retired in 1992 — for the first time. But after several years, “Baltimore called me. Syd Thrift called me and wanted to know if I’d un-retire. I went down there for two years. Syd got fired. I retired [again]. I was 80 years old. When I started playing ball, I made a pact with my wife. I said, ‘I’m going to stay in this game until I’m 80 and then I’m going to get out if it.’”25 That day came and Thompson left the game. He was a pro scout for Baltimore from 2001 to 2005.

As of May 2020, he remained a Lewistown resident.

He remembered that his son Timmy became a ballplayer also. “Then he became a coach and a teacher. He retired. He was 73 years old when he passed away. Bone cancer. He was a sports announcer and he was doing a TV show and he was interviewing a coach and he turned his neck to say something to the coach and — we have film of it — he turned his head and broke his neck. He spent three months in the hospital. He had a brace on his neck. Finally, he said to me he wanted to go home to die. We arranged for him to go home and in three weeks he ended up dying. We were there. My wife and I were both with him.

“He had two girls. They both live here in town. One of them takes care of my wife and I. We’re both crippled. My wife fell and broke both hips. We both have walkers and wheelchairs. We both use them.

“I have two metal knees. One of them has completely deteriorated. I’ve been in three nursing homes because I come up with…they don’t know what. They think somewhere along the line I took some kind of antibiotic and over a year’s time, I guess, it affected all my organs. And I’ve got burn marks all over my body. They look like blisters. They couldn’t ever figure out where it came from. They figure it was an antibiotic. I’ve had pneumonia a couple of times. It’s one thing after another. Now this leg has deteriorated. I only have one leg to walk on. The doctor who did the operation has died.”26

There aren’t many couples who can look back at nearly 80 years of marriage. Thompson told Anne Keene, “I got the right girl. We’ve had a great life. We’re both laid up now. We can’t do anything about that, but at least we’re together.”27

Tim Thompson died at home in Lewistown on October 25, 2021. His wife Lois died two days later, on October 27.

Last revised: October 29, 2021

Acknowledgments

Anne R. Keene was the inspiration for this biography, and her interviews with Tim Thompson provided very important information. Rod Nelson, chair of SABR’s Scouts and Scouting Committee, provided very helpful information.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and Thompson’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Notes

1 Bill Nowlin interview, January 8, 2020. While in high school, Thompson also played football — and the bass drum in the band.

2 Tim Thompson interview with Anne R. Keene on December 16, 2019. Thompson explained his one visit to the mine. “One time I went down with him on a weekend, down three or four miles, years ago when they were digging coal with a pick and shovel. They’d lay on their back and pick the coal, It would fall on their face and they’d put it on their chest and then push it out in the hole. That’s what I saw. I got claustrophobia from that and I made up my mind there’s one thing I would never do and that’s go into a coal mine. I never did after that one day.”

3 “Charles Lemoine Thompson,” Kansas City Athletics yearbook, 1957. In a December 21, 2019 interview with Bill Nowlin, Thompson said his understanding was that his father had had a two-week tryout with the Cardinals.

4 Anne R. Keene interview.

5 Anne R. Keene interview.

6 Anne R. Keene interview. U.S. Naval Air Station, Sunnyvale, California was more commonly known as Moffett Field. See https://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/wwiibayarea/usn.htm. There were 12 LTA (lighter-than-air) airships stationed at Moffett Field.

7 Anne R. Keene interview. Not one ship escorted by a blimp was ever sunk, reports CTC Edward E. Nugent, in an informative summary of the role than lighter-than-aircraft played during the Second World War. See https://www.bluejacket.com/usn_avi_ww2_blimps.html. Japanese submarines were never the threat to the West Coast of the United States that German submarines had been on the East Coast. For more information, see http://militarymuseum.org/NASMoffettFld.html

8 Bill Nowlin interview.

9 Combined from 2019 interviews with Anne R. Keene interview and Bill Nowlin.

10 Anne R. Keene interview.

11 Bill Nowlin 2019 interview.

12 Bill Nowlin 2019 interview.

13 Thompson also recounted an anecdote about Sandy Koufax. “One night, I asked, ‘Sandy, did you ever throw a spitter?’ He said, ‘What are you talking about?’ ‘Well, you spit a little bit on your hands, on your fingers, and you just touch the end of the ball with your fingers lightly and the ball will move different directions.’ He said he’d try it. I gave him the sign for that and he threw the ball — and as true as I’m sitting here, you could see the ball coming with stuff flying off of it. The umpire grabbed ahold of me and said, ‘What was that?’ I said, ‘What are you talking about?’ He said, ‘That ball. What was on that ball?’ I said, ‘I don’t know. Let’s see’ — and I tried to wipe it off. Sandy had spit in the middle of his hand and the ball was soaking with spit on the ball.” Bill Nowlin interview.

14 Arch Murray, “Sam’s ‘Now a Name Instead of a Number,’” The Sporting News, March 15, 1950: 20.

15 The source of this reminiscence is unknown. It derives from a wiki at https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Tim_Thompson. Thompson verified the story in a telephone conversation on June 6, 2020.

16 A big-league catcher — possibly Mike González — may have worn glasses before Courtney.

17 Associated Press, “Gets First Hit Since July 23; A’s Win, 1 to 0,” Chicago Tribune, August 20, 1957: B2.

18 Anne R. Keene interview.

19 Anne R. Keene interview. See also “Tom Lasorda to Scout Southland for Dodgers,” Los Angeles Times, December 8, 1952: A5. The article mentions Thompson replacing Lasorda in Pennsylvania. Thompson was very close to the Lasorda family. He told Anne Keene: “I lived with him! I knew Tom’s family — his brothers and everything, Many nights Tom and I would sit and eat pepperoni. I knew his family. I knew his mother and dad. I spent a lot of time with Tom and his family. They always called me their ‘extra son.’ Tom and I roomed together for four different years — in Brooklyn, in Puerto Rico, in Cuba, and in Kansas City. Then Tom was sent to Denver.”

20 Bill Nowlin interview.

21 Anne R. Keene interview. Thompson said he was one of seven scouting supervisors the team had at the time.

22 “Cards Add Two Scouts,” New York Times, January 25, 1965: S7. Thompson’s title was scouting supervisor.

23 Bill Nowlin 2020 interview.

24 Bill Nowlin 2020 interview.

25 Bill Nowlin 2019 interview.

Full Name

Charles Lemoine Thompson

Born

March 1, 1924 at Coalport, PA (USA)

Died

October 25, 2021 at Lewistown, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.