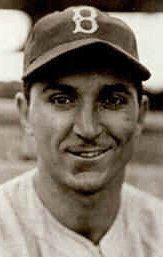

Al Campanis

Eight words: “They may not have some of the necessities.” Those words made Dodgers general manager Al Campanis a pariah. He tried to explain that he had not said what he meant or meant what he said, but his reputation was wrecked. His self-destruction focused a spotlight on Major League Baseball’s shameful record in hiring minority managers and executives, although the attention generated more talk than action.

Before his muddled insults of African Americans on ABC’s Nightline in 1987, Campanis was one of baseball’s great teachers and scouts. He wrote the book on how to teach the game. The Dodgers’ Way to Play Baseball, published in 1954, was translated into at least four languages and became a standard text for youth coaches. His teaching bible was borrowed from his revered mentor, Branch Rickey. Fourteen tapes of Rickey’s spring training lectures were among his prized possessions.

He devised a grading system for scouts, a 60-to-80 scale to turn their opinions of young players into hard numbers. Later converted to a 20-to-80 scale, it became an industry standard.

The man who was reviled as a racist had played alongside Jackie Robinson and signed Sandy Koufax and Roberto Clemente. Their portraits hung on his office wall — an African American, a Jew, and a Puerto Rican.

Alexander Sebastian Campanis came from a fractured Greek-Italian family. He was born Alessandro Campani on November 2, 1916, on Kos, one of the Greek Dodecanese (Twelve) Islands in the Aegean Sea. His mother, Aphrodite Hazzis, was an island girl who fell in love with an Italian army captain, Giuseppe Campani. When she brought their son to Italy, the wealthy, aristocratic Campani family rejected her because she was a foreigner. According to one source, the family had her committed to an asylum for the insane, but she escaped and took 5-year-old Alessandro to the United States in 1922. Campanis is the Greek version of his surname.1

Mother and son moved in with her brother in New York, where she found work as a seamstress. “My mother worked hard to support the two of us,” Al remembered. “We did not have much money and she used to buy a few pennies’ worth of lentils and make soup from them. We ate that soup because we were poor, but my friends used to come around and beg for that soup.”2

They lived in a Manhattan neighborhood with many Puerto Rican immigrants, and Al learned to speak Spanish while speaking Greek at home and English in school. A gifted athlete, he grew to 6 feet and 185 pounds. After high school he was offered a professional baseball contract and an athletic scholarship to New York University. His mother chose for him. He was a speedy halfback for NYU’s football team, played second and third base in baseball, and captained both squads.

When he presented his diploma to his mother in 1940, she gave her blessing for him to sign with the Dodgers. At the end of his first season, in Class-B Macon, Georgia, he married Basiliki Georgiades, another Greek immigrant, who was called Bessie. Three years later the switch-hitter batted just .207 for Double-A Montreal, where he learned French, his fourth language. Despite his weak bat, the Dodgers brought him up for a September trial in the talent-starved wartime season of 1943. He got into seven games at second base with two singles in 20 at-bats.

Bessie was expecting the first of their two sons when Al was drafted into the Navy in October 1943. He spent the next two years playing ball and conducting physical training for sailors at stateside bases. He was naturalized as a US citizen in 1944.

Returning to civilian life at 29, Campanis knew he had little chance of making the majors. He wanted to manage in the Dodgers farm system, but club president Rickey sent him back to Montreal in 1946 to play shortstop next to Robinson. In his historic first season in white baseball, Robinson was learning to play second base. Campanis often recalled how he helped the new man master the double-play pivot. When Robinson heard this years later, he told writer Roger Kahn, “Well, tell him I guess I could have worked out the pivot by myself.” Then he added, “No, don’t tell him. Al Campanis was a good guy. He was very good on integration when it counted.”3 Robinson died in 1972; he was not around to defend Campanis when it counted.

Campanis played another year at Montreal, then managed for three seasons in the lower levels of the Dodgers’ system. The farm director, Branch Rickey Jr., thought he had the makings of a future general manager and brought him to Brooklyn in 1950 as a front-office assistant. Rickey Sr. sent him to Mexico to use his Spanish in the search for prospects.

The Scouting Mind

Campanis began making annual trips to Latin America, mining the baseball hotbeds of Cuba (where he found Sandy Amoros), Puerto Rico (Clemente), and Mexico as well as Nicaragua and the Dominican Republic, then uncharted territory. In summers he scouted in New York City and on Long Island.

Rickey instructed his scouts to look for running speed, strong arms, and power bats because he believed those traits could not be taught. Campanis added: Find boys with a positive attitude because they are more likely to conquer the failure that is the essence of baseball.4

Scouts and their front-office bosses searched for ways to make their eyeball impressions look like objective evaluations. Rickey used “A” for average with + or ++, and “0” for below average. Campanis’s system graded players from 60 to 80 with 70 as major-league average.5 The number system, subjective as it was, was adopted throughout the game.

Behind the pseudo-scientific façade, Campanis clung to the oldest of scouting dogmas. “You ever hear of ‘the good face?’” he asked. “Well, I never used to sign a boy unless I could look in his face and see what I wanted to see: drive, determination, maturity, whatever.” When he became the Dodgers’ scouting director, he demanded of his scouts, “Tell me about his face.”6

He stressed the need to learn about a young player’s character as well as his athletic ability and baseball skills. “A scout can learn more about a boy from his attitude toward his parents and brothers and sisters than he can from the boy’s attitude toward his schoolmates.”7

In a 1960 article for Esquire magazine, Campanis said, “Our scouts are really super-salesmen. First they have to find out who really controls the family—dad or mom.”8 He delighted in telling how he stole New Yorker Tommy Davis from the Yankees by cultivating Davis’s mother, though a phone call from Jackie Robinson to the high schooler didn’t hurt. He ingratiated himself with Koufax’s stepfather, a lawyer, and signed the boy for $14,000.

Except for Koufax and Clemente, the Dodgers stayed away from big bonuses in the 1950s because of the rule requiring bonus babies to spend two years on the major-league roster. Campanis’s scouts signed Hall of Famers Don Drysdale and Don Sutton, five Rookies of the Year, and countless all-stars. For every whale, the club handed out contracts to hundreds of big fish in small ponds who sank without a ripple when thrown into larger lakes.

Utility Man

Campanis did everything for the Dodgers except laundry. Besides scouting amateurs in the United States and Latin America, he and chief scout Andy High followed the Yankees for a few weeks before the Dodgers faced them in the World Series. When he traveled with the team, he roomed with broadcaster Vin Scully.

Campanis did everything for the Dodgers except laundry. Besides scouting amateurs in the United States and Latin America, he and chief scout Andy High followed the Yankees for a few weeks before the Dodgers faced them in the World Series. When he traveled with the team, he roomed with broadcaster Vin Scully.

He was in his element at Dodgertown, the spring training base in Vero Beach, Florida. In the 1950s more than 500 players from all levels of the organization, Class D to the majors, assembled each year for a baseball school with Campanis as principal and Rickey’s principles as the textbook. “Given equal talent, the Dodgers will win every time,” he boasted. “We’re one of the only organizations to teach fundamentals uniformly throughout the system. We simply play better baseball than the other people.”9

As field director in spring training, he planned and supervised the practices, led the players in morning calisthenics, and served as the public-address announcer for some exhibition games. Year-round he conducted clinics for youth players and coaches, and worked the banquet circuit for the Dodgers. He even held a tryout camp in a 1953 movie, Big Leaguer, starring Edward G. Robinson. With all the hats he wore, Campanis was nicknamed “Chief.”

Away from the field, Al and Bessie were accomplished ballroom dancers, favorites at owner Walter O’Malley’s Christmas parties. The golf course was a different story; Campanis’s only prize was for the highest score in the club’s spring tournament.

Once his son Jimmy made a presentation at school about Jackie Robinson. The man himself walked into the classroom as the “show” in Show and Tell, a favor to Jimmy’s father.10

New World

When O’Malley’s plan to move to Los Angeles became common knowledge in 1957, the Yankees offered Campanis a job that would keep him at home in New York. He turned it down, and the Dodgers rewarded him with a promotion to director of scouting. He had been doing the job without the title for several years.

He worked for vice presidents Buzzie Bavasi, the general manager, and farm director Fresco Thompson. For 18 years, those three men and O’Malley made the Dodgers into a model franchise and the majors’ most profitable one.

O’Malley anticipated, correctly, that he would strike gold in California. With the move, he authorized spending more than $2 million over the next three years to sign amateur players. The majors had repealed the bonus rule so that bonus babies could be sent to the minors, and Campanis and his super-salesmen freely tapped O’Malley’s checkbook. The club gave $108,000 to the massive Ohio State slugger Frank Howard and $75,000 to Ron Fairly of NCAA champion Southern Cal, among about 100 players signed during the three-year spree.

By 1962 Howard and Fairly joined the lineup with five other farm system products: John Roseboro, Jim Gilliam, Maury Wills, Willie Davis, and Tommy Davis. Homegrown pitchers Koufax, Don Drysdale, and Johnny Podres anchored the staff. The club won 102 games but lost the pennant to the Giants in a playoff. Two pennants and World Series championships followed in 1963 and 1965, with another pennant in ’66.

The Golden Age of the baseball scout ended when the major leagues adopted the amateur draft in 1965. Since players could only sign with the team that drafted them, scouts no longer needed to be super-salesmen competing to win over teenagers and their parents. Naturally, the Dodgers opposed the draft. “We have money,” Campanis explained, “and we’re already committed to growing our own talent. And besides, California would be an ideal area to sign amateurs on the open market.”11

As the sixth-place team in the National League in 1964, Los Angeles had the eighth choice in the inaugural draft. Despite the relatively favorable slot, the draft was a bust. Only two of the Dodgers’ 32 picks went on to significant major-league careers. Alan Foster pitched for five teams in 10 years with middling success. The 10th-round choice got away: Pitcher Tom Seaver refused to sign and enrolled at Southern Cal. Adding to the bitter taste, the first player chosen in the draft, by the Kansas City Athletics, was Rick Monday of Arizona State, who had turned down a reported $20,000 bonus from the Dodgers when he graduated from Santa Monica High, just 17 miles from Dodger Stadium.12

Three years later Campanis and his scouts hit the jackpot. The Dodgers’ 1968 draft was the most bountiful in history: Steve Garvey, Ron Cey, Davey Lopes, Geoff Zahn, Bobby Valentine, Bill Buckner, Tom Paciorek, Joe Ferguson, and Doyle Alexander.

Although the draft robbed the Dodgers of their financial advantage, the ’68 bonanza proved that scouts still counted in the new baseball world. More successful drafts followed. And Campanis would be around to reap the benefits.

The Chief

The club’s 18 years of front-office stability ended after the 1968 draft when general manager Bavasi left to become president and part-owner of the expansion San Diego Padres. Following his custom of promoting from within, O’Malley named Fresco Thompson as Bavasi’s successor, but Thompson died of cancer just five months later.

After 28 years in the organization, Campanis was elevated to vice president of player personnel and scouting, with most of the duties of GM. To complete the transition, O’Malley announced that his son, Peter, would succeed him as president the following year, though he remained as chairman and a power in ownership circles.

Campanis’s first move: He traded his son Jim, a 24-year-old catcher who had had three trials with the Dodgers. He said it was for the boy’s own good; he was afraid teammates would think Jim was his father’s spy in the clubhouse.

Campanis inherited a mess. Koufax had retired after the pennant-winning 1966 season, and Wills and Tommy Davis were traded. For the first time in 30 years, the Dodgers posted back-to-back losing records in 1967 and ’68.

“We gotta be bold,” O’Malley told his new GM. “Don’t be afraid to take chances.” Campanis’s version of that advice was a quote from Shakespeare: “our doubts are traitors and make us lose the good we oft might win by fearing to attempt.”13

He did not fear to attempt. Bavasi had relied on the deep farm system to fill roster holes, but as many minor leagues folded, the organization had shrunk to seven teams, from two dozen in the 1950s. Facing a rebuilding job, Campanis had to become an active trader.

After the club failed to reach the postseason in 1970 for the fourth straight year, he acquired the controversial slugger Dick Allen (then called Richie). “I’m not trying to paint this guy as an angel,” Campanis said. “Don’t misunderstand me. But the checkouts on him with former teammates were solid.”14

Allen delivered 23 homers and a 151 OPS+ in 1971 as the Dodgers took the NL West race down to the final day before finishing second behind the Giants. But manager Walter Alston wouldn’t speak to the star. “I remember Dick saying, ‘Maybe today’s the day he’ll talk to me,’” Bobby Valentine said. “Most of the players loved [Allen],” pitcher Bill Singer commented, “but he was the kind of free spirit that would drive a manager nuts.”15 Siding with his manager, Campanis traded Allen to the White Sox for left-hander Tommy John. To replace the big bat, he acquired Frank Robinson from Baltimore, but the two-time MVP clashed with Alston. Robinson, too, was traded after one unhappy season.

Campanis was patching weak spots with veterans while waiting for the farm system’s new crop to ripen. The harvest began in 1973 when the Dodgers debuted a new infield on June 23. Steve Garvey, a scatter-armed third baseman, moved to first to complete a homegrown quartet that stayed together for 8½ years: former outfielders Davey Lopes and Bill Russell at second and short, and Ron Cey at third. But the club finished second in 1973 for the fourth straight season.

Still looking for a power bat to support his strong pitching staff, in 1974 Campanis brought in center fielder Jimmy Wynn from Houston. He also added bullpen stopper Mike Marshall from Montreal. The rebuild was complete. The Dodgers won their first pennant since 1966 and the first on Campanis’s watch. Wynn contributed 32 homers, an LA Dodgers record at the time, and Marshall pitched in a mind-bending 106 games, becoming the first reliever to win a Cy Young Award. But the club fell to Oakland in the World Series.

Cincinnati’s Big Red Machine bulldozed Los Angeles back down to second place for the next two years. After the 1976 season Walter Alston retired, ending 23 years of stability in the dugout. Some players thought the 64-year-old Alston was slipping, but others believed he was shoved out because the Dodgers were afraid of losing third-base coach Tommy Lasorda, who had other offers to manage. Lasorda had managed many of the players in the minors and had been a Campanis favorite since he hired the left-handed former Triple-A pitcher as a scout.

The rookie manager was already a veteran bullslinger. He thanked “the great Dodger in the sky” for the opportunity.16 Some critics dismissed Lasorda as a phony and a celebrity hound — when he managed his first game at Dodger Stadium, Frank Sinatra sang the national anthem — but he was a relentless competitor. “Every game was the most important game on earth,” pitcher Orel Hershiser remembered. “I don’t want you to try,” Lasorda told the players. “For what we’re paying you, I want you to do.”17

Now the Dodgers were Campanis’s team. The 1977 edition was also a different kind of LA Dodgers team, a throwback to Brooklyn’s Boys of Summer who bludgeoned the opposition. Garvey, Cey, and trade acquisitions Reggie Smith and Dusty Baker each hit 30 or more home runs to power the club to another pennant. And another in 1978. The club set major-league attendance records in both years. But — shades of the old days in Brooklyn — the Yankees beat them in both World Series.

The GM had to deal with personnel problems on and off the field: Dick Allen’s insubordination, a fight between stars Sutton and Garvey, Steve Howe’s cocaine addiction, Steve Sax’s inability to throw the ball straight. Campanis confronted one issue that few men of his generation were equipped to handle. Glenn Burke, a speedy young outfielder once compared to Rickey Henderson, was a popular figure in the clubhouse although many teammates knew he was gay. Campanis offered him a bonus if he would get married — to a woman, of course. When Burke refused, the image-conscious Dodgers traded him to Oakland for an over-the-hill Bill North.18

Even as the Dodgers slipped backward in 1979 and 1980, Campanis’s scouts and draft choices were still producing. Pitcher Rick Sutcliffe was the 1979 NL Rookie of the Year, the first of the team’s four winners in a row: Howe, Fernando Valenzuela, and Sax followed.

The Dodgers’ drafts during the 1970s had been wonderfully productive even though they usually selected near the bottom because they finished near the top of the standings. No. 1 picks included Rick Rhoden, Sutcliffe, Mike Scioscia, Bob Welch, and Howe, and they got Hershiser in the 17th round in 1979. That changed in the 1980s. During Campanis’s last seven years as GM, his drafts produced only three frontline talents: John Franco, Sid Fernandez, and Sid Bream, all in 1981. All were key contributors to pennant winners — for other teams after the Dodgers traded them.

When players gained free agency in 1976, the O’Malleys sat on their checkbook at first. After the club fell to a losing record in 1979, and after his father died, Peter O’Malley approved the signing of pitchers Dave Goltz and Don Stanhouse to contracts totaling $5.1 million. Both flopped. The Dodgers signed no more free agents during Campanis’s tenure.

The Chief almost let his next pitching star get away. Campanis agreed to pay Puebla of the Mexican League $50,000 for porky 18-year-old left-hander Fernando Valenzuela, but he walked out in a rage when the team upped the price to $120,000. Scout Mike Brito had to badger his boss into making the deal.19

Valenzuela brought Fernandomania to Dodger Stadium two years later. He won his first eight starts, including five shutouts, and became a must-see sensation, especially for Southern California’s huge Mexican-American population. He was the first rookie to win a Cy Young Award as he led the Dodgers to a World Series victory.

It was a weird way to win a championship. When the players’ strike interrupted the 1981 season, the Dodgers were declared first-half champions and backed into the playoffs despite a poor showing after the strike was settled. Cincinnati, with the best full-season record in the majors, was left out.

Los Angeles faced the Yankees again in the Series. It looked like more of the same when the Dodgers lost the first two games. Then they swept four in a row for their first championship in 16 years. Yankees owner George Steinbrenner apologized to fans for his team’s collapse.

Campanis’s first championship was his last. It was also the last ride for the longest-running infield combination in baseball history. After the Series, with young Steve Sax ready to take over second base, Campanis traded 36-year-old Davey Lopes to Oakland for a minor leaguer. A year later Ron Cey, 34, was dealt to the Cubs, and in the biggest shock of all, Steve Garvey, 34, was allowed to leave as a free agent. While some teammates resented Garvey’s carefully cultivated “Mr. Clean” image, he was the fans’ darling.

Campanis was following the playbook of his mentor Rickey, who said it was better to get rid of an aging player too soon rather than too late. Although the Dodgers won the Western Division without them in 1983, Cey and Garvey helped their new teams, the Cubs and Padres, win division championships in ’84. More damaging, the Dodgers farm system couldn’t replace them. New first baseman Greg Brock failed to live up to the hype, and the team had to move reluctant outfielder Pedro Guerrero to fill the hole at third, where he said, “I was thinking, don’t hit the ball to me.”20

When the farm system’s latest crops proved inadequate, Campanis had to import veterans like Bill Madlock, Enos Cabell, and Al Oliver who were near the end of the line. Despite strong pitching, the club slipped to a losing record in 1986, and the 1987 roster looked no better.

The Fall

On April 6, 1987, Campanis appeared on ABC-TV’s late-night program Nightline to commemorate the 40th anniversary of Jackie Robinson’s debut. The second guest was Roger Kahn, author of The Boys of Summer and a friend of Robinson’s. Another Robinson teammate, former Dodgers pitcher Don Newcombe, was scheduled to appear, but his plane was delayed. With the host, ABC News correspondent Ted Koppel, in Washington and Kahn in New York, Campanis was sitting behind the backstop in the darkened Houston Astrodome, where the Dodgers had played that night.

Koppel said he expected “rather bland if warm clichés about one of the great men in baseball.”21 A British-born foreign affairs specialist who knew nothing about the game, Koppel opened by tossing softball questions. After Robinson’s widow, Rachel, commented in a taped interview that her husband would deplore the lack of black managers and executives, Koppel asked Campanis why there were so few.

Campanis: The only thing I can say is that you have to pay your dues when you become a manager. Generally you have to go to the minor leagues. There’s not very much pay involved, and some of the better-known black players have been able to get into other fields and make a pretty good living in that way.

Koppel: You know, that’s a lot of baloney. There are a lot of great black players, great black baseball men, who would dearly love to be in managerial positions. Is there still that much prejudice in baseball today?

Campanis: No, I don’t believe it’s prejudice. I truly believe that they may not have some of the necessities to be, let’s say, a field manager or perhaps a general manager.

Koppel: Do you really believe that?

Campanis: Well, I don’t say that all of them, but they certainly are short. … How many quarterbacks do you have, how many pitchers do you have that are black?

Koppel: Yeah, but I gotta tell you, that sounds like the same sort of garbage we were hearing 40 years ago about players.

Campanis: No, it’s not garbage, Mr. Koppel. … So it just might be that, why are black men or black people not good swimmers? Because they don’t have the buoyancy.

Koppel: It may just be because they don’t have access to all the country clubs and the pools.

During a commercial break, producer Rick Kaplan remembered, “Ted was trying to help him. I’ve never seen Ted off-air try to bring the guy back and say, ‘Al, are you hearing yourself? Do you hear what you’re saying? Are you sure you don’t want to rethink that?’”22 When the interview resumed, Campanis dug the hole deeper.

Campanis: I have never said that blacks are not intelligent. I think many of them are highly intelligent. But they may not have the desire to be in the front office. I know that they have wanted to manage and some of them have managed. But they’re outstanding athletes, very God-gifted, and they’re very wonderful people.

(The interview, transcribed from YouTube, has been edited for clarity.)

Right after the program, Vin Scully, who hadn’t seen it, found his former roomie “pale and shaking.” “I think I fucked up,” Campanis told him.23 The next day he issued an apology, saying “my statements have been misconstrued” and adding, “This is the saddest moment of my entire career.”

The reaction was brutal. Rachel Robinson was “appalled.” Hank Aaron said baseball couldn’t eliminate racial prejudice “because you still have people like Campanis with his beliefs.”24

“He just said what a lot of baseball people have been thinking for years,” observed Frank Robinson, the first black manager in the majors. “I’m glad it’s finally out in the open, so we can address it.”25

Those who knew him stepped up to defend him. “I don’t believe he has a prejudiced bone in his body,” Don Newcombe said. Maury Wills went to Campanis’s home, picked up a ringing telephone, and said, “This is Maury Wills, a friend of Al Campanis.” Campanis’s younger child, George, remembered his father whipping him because he spoke the “N” word, “the only time my dad took a belt to me.”26

Two days after the interview, Peter O’Malley forced Campanis to resign. “I told Al I didn’t have any choice,” O’Malley said later, “and he understood.”27

Trying to explain himself, Campanis told the Los Angeles Times’s Jim Murray, “When I said blacks lacked the ‘necessities’ to be managers or general managers, I meant the necessary experience, not things like inherent intelligence or native ability.”28 But “necessities” was no single slip of the tongue; he had rambled on in the same vein and worse.

A rumor circulated that he had been drunk. Not so, said writer Bud Furillo, who had been sitting near him in the Astrodome press box that evening: “He was drinking Coca-Cola.”29 Fred Claire, the Dodgers executive who succeeded him as GM, thought the 70-year-old Campanis was worn out at the end of a long day.30

To acquaintances, the interview sounded like typical Campanis — the manner of speaking, not the message. “He had a way of mangling the language,” Los Angeles Times writer Mark Heisler recalled. “As much as I liked the guy, he would go off the point and say something weird so often, people actually wondered if he was senile, or just pretending to be that way to confuse them.”31 The New York Times’s George Vecsey said Campanis’s convoluted conversations left listeners guessing what he was talking about. “He was a perfect example of why most of us should be cautious about appearing on live radio or television.”32

For years afterward, Tommy Lasorda repeated, “They hung an innocent man.”33 But nothing Campanis or his friends said mattered. He had written the first line of his obituary.

The backlash reverberated throughout baseball. Commissioner Peter Ueberroth enlisted an outspoken critic, the African American sociologist Harry Edwards, as a consultant on minority hiring. And Edwards hired Campanis to assist him. “It wasn’t a simple case of Al being a bigot,” Edwards said, “to say he was just a bigot is simply wrong — people are more complex than that. To a certain extent, it was the culture Al was involved with. To a certain extent, it was a comfort with that culture.”34

Ueberroth’s initiative produced headlines, but little change. Two years later the National League installed a black former player, Bill White, as its president, but White acknowledged that he made scant progress in persuading teams to add minorities to their executive ranks.35

Campanis was never able to rehabilitate his reputation. The only baseball job he could find was as general manager of an independent-league team, the Palm Springs Suns. He wrote an autobiography, but no publisher would touch it. The Dodgers didn’t shun him; O’Malley invited him to ball games, and he visited his successor, Fred Claire, in his old office to talk baseball. He was a ghost haunting Dodger Stadium.

His son Jim had played six years in the majors with Los Angeles, Kansas City, and Pittsburgh, where he was briefly a teammate of Roberto Clemente. His grandson Jimmy was drafted by Seattle in the third round in 1998 and topped out in Double A. Jimmy was the model for illustrations in his grandfather’s instruction book for children, Play Ball with Roger the Dodger.36

When he heard that Ted Koppel was in Los Angeles, Campanis called him, and they met amiably for coffee. “I think there are a lot of genuine bigots in this country,” Koppel said. “… I don’t think Al was one of them.”37

After suffering several strokes, Campanis died of coronary artery disease at 81 on June 21, 1998, Father’s Day. “He didn’t get a raw deal,” Harry Edwards said, “he got the deal he ordered up, but he was one of the most honorable men in the whole process and he handled it with class, with conscientiousness and with courage.”38

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Jan Finkel, and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Additional sources

Armour, Mark L., and Daniel R. Levitt, In Pursuit of Pennants (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2015).

Statistics and draft information from Baseball-Reference.com.

Trade information from Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Several accounts of Campanis’s family history appeared in the Los Angeles Times: John Wiebusch, “Campanis Finally Rewarded for Long Years of Waiting,” June 6, 1969: III-1; Charles Maher, “A Dodger Lineup You Don’t Hear Much About,” July 16, 1971: III-8.; and Mark Heisler, “A Man Worth Remembering,” Los Angeles Times, April 12, 1987, III-3. See also Diamantis Zervos, Baseball’s Golden Greeks (Canton, Massachusetts: Aegean Books International, 1998).

2 George Vecsey, “Seeds of Success from a Watermelon,” New York Times, May 9, 1981: 17.

3 Roger Kahn, A Season in the Sun (New York: Harper & Row, 1977), 39-40.

4 Kahn, A Season, 40-41.

5 Kevin Kerrane, Dollar Sign on the Muscle (New York: Fireside/Simon & Schuster, 1984), 34.

6 Kerrane, Dollar Sign, 124.

7 Bob Hunter, “Dodgers System Overflowing in Talent,” The Sporting News, April 4, 1962: 4.

8 “New Pitch in Baseball,” The Sporting News, May 4, 1960: 36.

9 Ross Newhan, “Alston Likes New Players, Promises They’ll Get Chance,” Los Angeles Times, February 23, 1970: III-1.

10 William Weinbaum, “The Legacy of Al Campanis,” espn.com, April 1, 2012. https://www.espn.com/espn/otl/story/_/id/7751398/how-al-campanis-controversial-racial-remarks-cost-career-highlighted-mlb-hiring-practices, accessed August 2, 2019.

11 Kerrane, Dollar Sign, 183.

12 United Press International, “Ex-Santa Monica Prep Top Man in Baseball Draft,” Los Angeles Times, June 9, 1965: III-5.

13 Milton Richman, United Press International, “Al Campanis: Exec of Year Front-Runner,” Long Beach (California) Independent, September 26, 1974: C-2; William Shakespeare, Measure for Measure, Act 1 scene 4.

14 Dick Young, “Young Ideas,” The Sporting News, April 10, 1971: 18.

15 Steve Delsohn, True Blue (New York: HarperCollins, 2002), 99-100.

16 Newhan, “Dodgers Get Their Man; It’s Lasorda,” Los Angeles Times, September 30, 1976: III-6.

17 Orel Hershiser on Dodgers TV broadcast, SportsNet LA, August 26, 2019.

18 Glenn Burke with Erik Sherman, Out at Home: The True Story of Glenn Burke, Baseball’s First Openly Gay Player (repr. Berkeley, 2015), 2.

19 Jason Turbow, They Bled True Blue (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019), 64.

20 Delsohn, True Blue, 163.

21 Weinbaum, “The Legacy.”

22 Weinbaum, “The Legacy.”

23 Steve Springer, “The Nightline that Rocked Baseball,” Los Angeles Times, April 6, 1997: C9.

24 “Some Answers No One Expected,” New York Times, April 8, 1987: B10.

25 Peter Gammons, “The Campanis Affair,” Sports Illustrated, April 20, 1987, https://www.si.com/vault/1987/04/20/106777673/scorecard, accessed August 2, 2019.

26 Newhan, “A Lifetime Destroyed by His Own Words,” Los Angeles Times, June 22, 1998: C1, C8.

27 Newhan, “Campanis, ex-Dodger Official Dies,” Los Angeles Times, June 22, 1998: A17.

28 Jim Murray, “The Bitter Lesson for Campanis: Just Say ‘No, Thanks,’” Los Angeles Times, July 2, 1987: III-5.

29 Delsohn, True Blue, 180.

30 Fred Claire with Steve Springer, My 30 Years in Dodger Blue (Sports Publishing, 2004), 65.

31 Delsohn, True Blue, 182

32 Vecsey, “Sports of the Times,” New York Times, August 23, 1998: S2.

33 Springer, “The Nightline.”

34 Weinbaum, “The Legacy.”

35 Warren Corbett, “Bill White,” SABR BioProject.

36 Jim Campanis Jr., Born into Baseball (Summer Game, 2016), unpaginated e-book.

37 Delsohn, True Blue, 183.

38 Weinbaum, “The Legacy.”

Full Name

Alexander Sebastian Campanis

Born

November 2, 1916 at Kos, Dodescanese Isl. (Greece)

Died

June 21, 1998 at Fullerton, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.