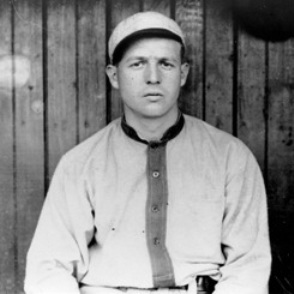

Vin Campbell

When Vincent Campbell became an overnight sensation with the Pittsburgh Pirates in May of 1910, there was a rush of adulation from fans, sportswriters and baseball executives. In the early 1900s it was unusual for a college man like Campbell to even play professional baseball. Vin was well-read, came from an affluent family, and was able to make his way in the business world as well as playing baseball.

When Vincent Campbell became an overnight sensation with the Pittsburgh Pirates in May of 1910, there was a rush of adulation from fans, sportswriters and baseball executives. In the early 1900s it was unusual for a college man like Campbell to even play professional baseball. Vin was well-read, came from an affluent family, and was able to make his way in the business world as well as playing baseball.

Arthur Vincent Campbell Jr. was born January 30, 1888, the son of Mary and Dr. Arthur V Campbell Sr., an oculist (ophthalmologist) in the Carondelet section of St. Louis, Missouri. Vincent Jr. had a younger brother, Cecil, who followed in his father’s footsteps as an oculist.

Commonly known as Vincent, Vin, or Vint, Campbell was an all-around athlete at Smith Academy in St. Louis, then at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. A catcher at Vanderbilt, he was better known for his exploits on the gridiron. Renowned sports columnist Hugh Fullerton wrote about Campbell’s prowess in a 1907 game against Michigan, then the nation’s premier college football team: “On every play a mass of curly, tow-colored hair flashed in the forefront of the battle and the loyal Southern rooters stood and screamed ‘The Demon! The Demon!’ Before the end of the first half the experts were inquiring about this human batting ram who was upsetting all the form of the game and demolishing the Michigan line. ‘The Demon’ was Campbell.”[fn]Hugh Fullerton, “Seeking the .300 Hitter,” in American Magazine and reprinted in Decatur Review, October 30, 1910.[/fn]

Vanderbilt lost only that one game against Michigan that year, and played the mighty Naval Academy to a tie. Although Campbell was a football star only one season, he was named the second team halfback on the All-Vanderbilt team by the Nashville-Tennessean and American, in 1912.

Campbell left college for a trial with the Chicago National League Baseball club in 1908. Upon his arrival for spring training, Chicago sportswriters had a field day teasing the “young dandy” dressed in a “champagne suit…wine waistcoat, sherry hat and yellow chartreuse shoes.”[fn]Chicago Daily Tribune, April 7, 1908.[/fn] The Cubs touted Campbell in Sporting Life as “a physical marvel and a sure comer,” and perhaps the fastest runner on the team. The twenty-year-old rookie stood six foot tall and weighed around 185 pounds. Though Vin threw with his right arm, he was a left-handed batter. Manager Frank Chance put Campbell through a rigorous spring training regimen and found the ex-collegian to be unpolished as a catcher, but kept Vin on the team as a third catcher to start the season. Johnny Kling and Pat Moran handled all duties behind the plate; Vin made only one appearance as a pinch-hitter on June 6 in a 14-0 rout of the Boston Braves.

The Cubs decided Campbell needed to develop skills at a position other than catcher, so they sent him to Decatur in the Three-I League. In his first game with the Commodores on June 23, Campbell made two hits. Following a few games as a catcher, Vin was permanently installed in right field and settled into the fourth spot in the batting order. He appeared in 84 games for Decatur and batted .279 in 315 at bats. Despite his exceptional speed, Campbell notched only 17 stolen bases. He also was a project afield, pulling in only 79 fly balls with 6 errors in 70 games in the outfield.[fn]“Seven Batted .300: Official 1908 averages of Three-I League,” Sporting News, November 19, 1908.[/fn]

That fall, the Atlanta club of the Southern Association drafted Campbell from Decatur, then purchased rights to the player from the Cubs. These shenanigans came to the attention of the National Commission, the ruling body of major league baseball, which fined the Cubs $250 for illegal farming of Campbell and declared him a free agent.[fn]Sporting Life, November 14, 1908.[/fn]

Manager Pants Rowland of the Aberdeen, Washington club in the Northwestern League, signed Vin for 1909. Rowland soon became dissatisfied with Campbell, fining him $50 for loafing on the base paths. Apparently he got the young player’s attention; Vin stole 72 bases for the Black Cats that season. Rowland returned the $50.[fn]“Rowland Fines and then Remits to Player,” New Castle News, April 1, 1915.[/fn]

Aberdeen pitcher Eddie Siever, who had spent three seasons with the Detroit Tigers, asserted that Campbell was much faster than Ty Cobb, generally regarded as the swiftest base runner in baseball.[fn]Aberdeen Herald, July 22, 1909.[/fn] A local observer commented that Campbell “can give a streak of lightning three feet the start of him and beat it to first base nine times out of ten.”[fn]“Sievers Lauds Campbell,” Washington Post, September 19, 1909.[/fn]

Lee Magee, a player in the Northwestern League who would spend nine seasons in the big leagues, also praised the young player: “I believe that Campbell is the fastest man in the country getting down to first base. If the ball he hits takes two hops before it gets to the infielder, Campbell will beat it out. He bats left-handed and gets away from the plate faster than any man I saw. He’s a fine base runner, hits well, covers a lot of ground in the outfield, and throws with considerable speed.”[fn]Pittsburgh Press, January 12, 1910.[/fn]

In July the Pittsburgh Pirates purchased Campbell from the Aberdeen club for $2,000. Campbell finished the season in Aberdeen, played in 158 games for the third-place Black Cats, and batted .280. However, he committed 26 errors to record the lowest fielding average (.892) among the league’s starting outfielders.[fn]“How Northwestern Players Performed,” Sporting News, November 4, 1909.[/fn] Campbell was a travelling shoe salesman based in St. Louis during the off-season until it came time to report to the Pirates.

Campbell impressed Pirates manager Fred Clarke in spring training and made the defending World Series champions as a reserve outfielder. A string of injuries among the Pirates’ outfielders gave Campbell an early opportunity to make an impression on manager Fred Clarke and Pirates’ owner Barney Dreyfuss.

On April 21 against the St. Louis Cardinals, Pirates right fielder Chief Wilson suffered a twisted ankle while making a play and was taken to the hospital. Pittsburgh baseball writer Alfred R. Cratty wrote that Campbell “leaped right into the heart of the fans by his vim, swiftness and also by the fact that he clouted in two scores first time up. A sprinter at college of the 10-second type, the lad gets over the base paths in whirl-wind style, is the dashing kind of tosser so valuable to America’s sport.”[fn]A. R. Cratty, “Campbell of Aberdeen,” Sporting Life, May 7, 1910.[/fn]

A day later against the Cardinals Campbell laid down a bunt in front of the plate and beat a perfect throw to first base. He then attempted to steal second base and the catcher’s throw beat him to the bag. Campbell made a “beautiful slide” to the outfield side to evade Miller Huggins’s tag and at the same time hooked his foot onto the bag. Later Vin went from first to third on a short single to right, and topped off the day’s accomplishments by snagging a long fly ball after a hard run and making a perfect throw to the plate to nip the runner attempting to score from third.[fn]Ralph S Davis, “Bucked a Hoodoo,” Sporting News, April 28, 1910.[/fn]

Chief Wilson returned to the lineup on May 4, but Vin would get plenty of opportunities. He didn’t have a chance to get comfortable on the bench before center fielder Tommy Leach went on the disabled list.

By early September Fred Clarke had grown tired of fans’ complaints about his declining skills and batting average. He decided to pull himself from the Pirates line-up and installed Campbell in his place for the remainder of the season. Upon returning to the regular lineup on September 8 Campbell made three hits, one a double, against the Cardinals. After a couple of games in center field, Campbell assumed the left field slot for good on September 11. In an article for American Magazine, Hugh S. Fullerton wrote that Fred Clarke “secured for Pittsburg possibly the greatest player of many seasons.”[fn]“Big Boost for Vincent Campbell,” Decatur Review, October 30, 1910.[/fn]

Though Campbell batted .326, second highest in the National League, there were obvious deficiencies in his game. Despite his amazing speed, Vin’s 17 stolen bases didn’t come near his number with Class B Aberdeen a year earlier. There also were complaints that he was impatient at bat because he didn’t draw many bases on balls. And Vin wasn’t considered a good fielder. The critics maintained that part of his fielding problem was undersized hands. Being sure-handed was a necessity because the baseball gloves of that era were little more than enlarged versions of leather gloves with extra padding.[fn]“Big Hands Aids Ball Players,” Washington Post, February 9, 1913.[/fn]

In an early version of sabermetrics, a sports writer came up with the formula that “during the past season Fred Clarke in 118 games, caught 284 flies, 2.41 per game with a fielding percentage of .967. Campbell in 74 games, gathered only 145 flies, or 1.96 per game, while he muffed enough to give him an average of .895.”[fn]“Campbell Muffed Outfield Flies,” Decatur Review, December 21, 1910.[/fn] Ralph Davis of The Sporting News defended Campbell’s defense, writing that he had “improved in fielding 50 percent this season.”[fn]The Sporting News, September 15, 1910.[/fn]

When it came time to renew the Pittsburgh players’ contracts, the praise turned to disbelief when Campbell notified the Pirates he would not play professional baseball in 1911 because he had taken a position with a prominent brokerage firm in St. Louis. Another story made the rounds that Campbell could not play baseball and maintain his social standing at the same time. Barney Dreyfuss was magnanimous in his response to Campbell’s ‘retirement’: “He gave the Pittsburgh club every bit of skill and energy in his make-up. Sorry to see him go, but at the same time I never stand in the way of a man bettering himself.”[fn]“A Fleet One Lost,” Sporting Life, March 11, 1911.[/fn]

Campbell didn’t completely give up the idea of playing professional baseball in 1911. That summer he played the outfield with the Ben Miller team of the St. Louis Trolley league. When the Pirates visited Sportsman’s Park to play the Cardinals in July, Campbell met with Fred Clarke. The Pirates manager expressed the desire that Vin return to the club. Campbell agreed, but he would have to ask the National Commission for reinstatement since his name was on the ineligible list.[fn]Ralph Davis, “Use for Campbell,” Sporting News, July 13, 1911.[/fn] Three days later, Campbell’s application for reinstatement was granted.

Campbell may have had another reason for wanting to return to Pittsburgh. Late in the 1910 season, he had been introduced to an attractive young woman in the grandstand at Forbes Field. The young lady was Katherine Munhall, member of a wealthy Pittsburgh family. “During his residence in Pittsburgh the blonde baseball player and the handsome Miss Munhall were together much of the time,” the newspapers reported. “The young woman never missed a game when the team was at home and ‘Vint’ Campbell frequently was driven to the Munhall home for dinner in Miss Katherine’s auto.”[fn]“Campbell to Wed and Quit Baseball,” Boston Daily Globe, October 14, 1912.[/fn]

Campbell rejoined the Pirates on July 10, 1911, in Brooklyn. Unfortunately for him, another fleet-footed outfielder, future Hall of Famer Max Carey, had become the Pirates’ regular center fielder. Campbell returned to the lineup as a pinch hitter three days later and struck out. Vin got into only 42 games with the Pirates, 21 of them in the outfield and the rest as a pinch hitter.

When Campbell visited Pirates’ headquarters during the Christmas holidays, he was amiable and indicated he was looking forward to signing his contract for 1912. So the Pirates’ brass was stunned in February when Campbell rejected the club’s salary offer and became a hold-out. Vin’s refusal to sign signaled the end of his days as a Pirate. Barney Dreyfuss had little patience with hold-outs unless a star quality player was involved. “For my part I don’t care whether Campbell signs or not,” growled the Pirates’ owner. “I see no reason why the failure of Campbell to accept his contract will hold back any one part of our program.”[fn]A. R. Cratty, “Pirate Points,” Sporting Life, February 24, 1912.[/fn]

Pittsburgh requested waivers on Campbell and the last-place Boston Braves refused to pass on the outfielder. The Pirates worked out a trade with the Braves that was consummated on February 12, 1912, with aging outfielder Mike Donlin going to Pittsburgh.

Though he reported late to the Braves and was temporarily suspended by manager George Stallings, Campbell was in the lineup for opening day that April. The Braves were a .500 team as late as May 4, but finished in last place for the fourth consecutive season.

Campbell batted second and put up good numbers including a .296 batting average in 681 plate appearances, and led the Braves in doubles (32) and runs scored (102). Two months into the season, Sporting Life reported on his outfield play, “Campbell of the Braves, formerly an uncertain and clumsy outfielder, has improved marvelously. He gets them near and far, covers an immense territory, and is sure as a steel trap.”[fn]Sporting Life, June 29, 1912.[/fn] Though he committed 24 errors, Vin’s fielding average was 42 points higher than in 1910.

A few days after the Braves’ last game of the season on October 3, Campbell announced his intention to marry and retire from baseball to enter the automobile supply business. On October 16 Vin married Katherine Munhall at St. Paul’s Cathedral in Pittsburgh.

News regarding Campbell’s status in baseball was not forthcoming until the following January when it was suggested Vin might reconsider his decision to retire if a deal could be arranged for him to play for John McGraw’s National League champions. It was said the Braves wanted Giants’ outfielder Josh Devore, but the talk of a trade with New York fizzled.[fn]Harry D. Cole, “New York Baseball,” Sporting Life, January 25, 1913.[/fn]

Campbell did not play baseball in 1913, concentrating on his position as president of the Keystone Motor Supply Company in Pittsburgh. However, he wasn’t ready to give up baseball just yet and within a year saw an opportunity to make a great deal of money in a new major league operating outside the jurisdiction of Organized Baseball.

In 1913 the average salary for an everyday player in the major leagues was around $3,500. A year later the outlaw Federal League began to pay double what ball players were earning in the “Organized” major leagues. Bill Phillips, manager of the Federal League club in Indianapolis, lived a few miles from Pittsburgh and paid a visit to Campbell. “Whoa Bill” convinced the retired outfielder to sign a contract with the Federals on March 6, 1914. Despite being out of baseball for a year, Campbell would be paid $8500 to play for the Hoosiers in 1914.[fn]Indianapolis Star, March 6, 1914.[/fn]

Campbell went on a tear in the first half of the Federal League season. At Kansas City on April 20, his “terrific clout” with the bases full was good for three bases in the Hoosiers’ 7-2 win over the Packers. Two days later the Hoosiers trailed Kansas City, 3-2, in the first of the ninth, when George Mullin tripled to right and scored on an infield hit by Campbell, Vin’s fifth single of the game.

After Campbell’s game-winning triple in the tenth inning on May 27 at Pittsburgh, Sporting Life commented, “Campbell’s speed on the base paths and in the field continue to be nothing short of marvelous.”[fn]Sporting Life, June 6, 1914.[/fn] On July 14 Campbell had a home run, triple and single in four at bats, in a loss to Pittsburgh.

During a game against Baltimore on August 11, Campbell was struck in the head by a pitch thrown by Jack Quinn. Vin was “knocked out a while” before regaining consciousness. He staggered to first base only to retire to the bench for the remainder of the contest. He missed the second game of a double-header but was back in the lineup, leading off, the next day. Nagging injuries would cause Campbell to miss several games and diminish his batting numbers. After consistently hitting over .350 the first half of the season, Vin finished the year with 26 stolen bases and a batting average of .318 in 134 games.

Indianapolis won the Federal League pennant in 1914, but when it came time to renew his contract the club’s offer was less than the previous season because the earlier contract had included a signing bonus. Vin and third baseman Bill McKechnie, friends from their days with the Pittsburgh club, became holdouts.[fn]Eddie Ash, “Campbell and M’Kechnie virtual Hoofed ‘Holdouts’,” Indianapolis Star, February 19, 1915.[/fn] Neither side would budge on Campbell’s salary demand for 1915. In late March the Indianapolis club’s directors were forced to give up their franchise because of its debts and the team was transferred to new owners in Newark, New Jersey. The primary owner of the Newark team was a man with very deep pockets, Harry Sinclair, president of Sinclair Oil Company.

Campbell reported to the Newark training camp near Valdosta, Georgia, and was signed to a one- year contract by club president Patrick T. Powers for a salary said to be $7,875.[fn]Sunday Indianapolis Star, March 28, 1915.[/fn] Composed mostly of players from the 1914 Hoosiers, Newark slipped to fifth place although the “Peps” had a winning record. Campbell usually played right field and made only 12 errors, the first time in the big leagues he had fewer errors than assists (15). Vin batted .310 in 127 games, but his extra base hit numbers dropped from 41 to 29. His home runs dropped from 7 to 1. That September the Newark club renewed Campbell’s contract with a five per cent increase.[fn]Pittsburgh Gazette Times, July 28, 1916.[/fn]

In December 1915, the Federal League reached an agreement with the American and National Leagues to end the baseball war that had brought heavy financial losses to all parties – except the players. In the settlement, the Federal League went out of business. Two Federal League clubs were allowed to take over major league teams and the Federals could auction the remaining players to the highest bidders.

Campbell was not interested in signing at a drastic cut in pay and rebuffed all offers that came his way. On July 27, 1916, he filed a suit seeking $8,268 from the Newark Federal League club claiming it did not live up to the contract he had signed the previous September.

Campbell’s breach of contract suit went to trial in New York City in October 1917. Despite a claim by the defendants that Campbell refused offers to play with either the St. Louis or Cincinnati clubs of the National League, the jury awarded the plaintiff $5,957 due from his 1916 Federal League contract.[fn]Boston Daily Globe, October 17, 1917.[/fn]

Following his third retirement from baseball, Campbell and his Munhall in-laws were involved in the tire business for almost twenty years in Pittsburgh. In the early 1930s, Vin moved to East 25th Street in New York City, where he managed a chain of tire stores. Vincent and Katherine had two daughters and a son, Arthur Vincent Campbell III. Vin Campbell died in Towson, Maryland, November 16, 1969, at the age of eighty-one. He is buried in Bellefontaine Cemetery in St. Louis.

Sources

Baseball-Reference.com, Indianapolis Star, Pittsburgh Gazette Times, Pittsburgh Press, Sporting Life, Sporting News, and U.S. Census reports, 1880-1940. The image of Vin Campbell in uniform of the Pittsburgh Pirates (2317.90_HS_PD.jpg) was provided by the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

Full Name

Arthur Vincent Campbell

Born

January 30, 1888 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

Died

November 16, 1969 at Towson, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.