Virgil Cheeves

Poet Alexander Pope gave us the phrase “Hope springs eternal in the human breast.” Nowhere is this optimism more prevalent than among fans at baseball spring training. In 1921 the Chicago Cubs, under former star and new1 manager Johnny Evers, went to Catalina Island for spring training for the first time. They stayed only a week before moving on to Pasadena. In that brief time, it became obvious that young Virgil Cheeves was destined to join Grover Alexander, Jim Vaughn, and Lefty Tyler on what fans hoped would be a dominant staff.

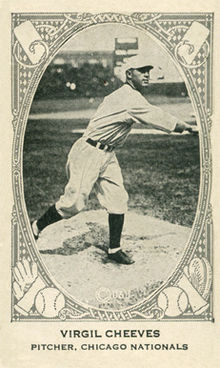

Fans dream of adding a young phenom to their team and Cheeves put stars in their eyes. At six feet tall and 190 pounds, he was a powerful-looking lad. The fans had seen his fastball in a September 1920 call-up, and an intriguing winter report noted that “Alexander is instructing him in the fine points of the game.”2 Yet, as so often happens, the early excitement turned to disappointment. Cheeves gave the Cubs fans two decent seasons totaling 23 wins, but a bad elbow ended the dream.

Virgil Earl Cheeves was born on February 12, 1901, in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. His parents were Cherokee descendants, Ruben Tolbert and Minnie Ella (Karr) Cheeves. The parents were from Mississippi and moved about the Texas/Oklahoma region. (Of their six children, the first and last were born in Texas, the others in Oklahoma.) Virgil’s grandfather was a farm laborer and raised cattle. Ruben learned carpentry and passed that trade down to his five sons.

All the brothers were baseball players. Growing up where he did, Cheeves had been around professional baseball for years. He remarked, “I just naturally had to learn how to play.”3 The oldest, Carl, was the only one not to play professionally. He went to spring training in 1920 with Virgil but returned home to help with the carpentry business. Dave had the longest career and the most games played from 1926 through 1936. He won the Western Association batting crown in 1934.

Cheeves spent his first decade in Oklahoma before moving to Dallas, Texas, where he attended Bowie High School for a year.4 After leaving high school he played on the sandlots and worked as a bicycle delivery boy.5 James “Curley” Maloney, a veteran Texas League player, saw him in action and invited him to join his team in the Dallas City League. In 1919 Cheeves became an outfielder and pitcher for Maloney’s I. M. Kahns team. Maloney helped to refine Cheeves’ motion, taught him a pickoff move, and preached the concept of pitching, not just throwing. When the City League season ended, Cheeves played with semipro teams in Childress, Texas and Mangum, Oklahoma.

In 1920 Maloney was named manager of the Eastland Judges in the Class D West Texas League. Cheeves was one of his first signings. Virgil made his professional debut in the town of Mineral Wells on May 1 against the Resorters in front of 2,000 spectators. He struck out seven and walked four on his way to a 9-3 victory. His pitching opponent was Henry Meade, who went on to lead the circuit in wins.6

The Eastland team finished in last place. Cheeves was its ace and won 14 of 26 decisions, including both ends of an August 26 doubleheader. Scout Jack Doyle of the Chicago Cubs saw him pitch on a day when “his fast one smoked by the batters and his slow ball was teasingly baffling.”7 Doyle and Maloney arranged for Cheeves to join the Cubs. He debuted at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field on September 7. With the Pirates ahead 7-4 he entered the game in the eighth and retired Bill McKechnie, Charlie Grimm, and Babe Adams in order. The Chicago Tribune called him “Paul” and noted that he threw with a “free motion.”8

Cheeves was given his first start on September 17 in Philadelphia. In the opening frame he walked Johnny Rawlings and gave up a triple to Cy Williams, then shut down the Phillies through seven innings on four hits. The Cubs rallied for three runs in the ninth for the victory. Sweetbread Bailey got the win with relief help from Alexander.

Cheeves made three more September appearances for the Cubs. He had no decisions and would have had a sparkling ERA except for the St. Louis Cardinals, who scored four runs against him on September 27 in a 16-1 win. He returned to Texas and worked as a carpenter that winter.

When the Cubs opened spring training on Catalina in 1921, the players stayed in a newly built hotel, but as part of their regime to get into shape, they walked three-quarters of a mile to another hotel for breakfast. They then headed for the practice field. After practice they had dinner at their residence hotel. Evers welcomed 15 pitchers to camp; five were rookies. Cheeves, joined by fellow rookies Percy Jones and Buck Freeman, made the Opening Day roster.

Cheeves’s deceptive motion made his offerings difficult to pick up and he popped “his fast ball into the big mitt with a bang.”9 In addition to the fastball, Cheeves claimed to be “the first” to use the knuckleball in the major leagues.10 Lew Moren, Eddie Cicotte, and Eddie Rommel are recognized as using the knuckler before Cheeves’s arrival. Where and when he learned to throw it is unknown.

The excitement about the pitching staff was short-lived. The Cubs won six of eight to open the season, but Tyler was not himself. Despite all the hype, Cheeves, at age 20, was not the first rookie in the rotation. That honor went to Freeman, age 24, who pitched slightly more than Cheeves with nearly the same results for the season. Cheeves got his first start on May 19 versus the Giants but was pulled in the third. He did not join the rotation until June 25, when he beat Cincinnati, 6-2. He was described as “hurling as steady and true as an old timer.”11

When Evers was replaced at the helm in early August by Bill Killefer, Cheeves remained in the rotation. He posted an 11-12 mark for the season. He earned a reputation as a “Giant Killer” with four wins over the New York squad. Two were complete games and the others were in short relief. His lone shutout came on September 18, when he allowed Brooklyn just six hits in a 1-0 victory. Cheeves returned to Dallas for the winter.

Before spring training in 1922, Killefer had concerns about Cheeves’s weight and training. The pitcher reported to Excelsior Springs, Missouri for a week to get into shape before boarding the team train in Kansas City for the trip west. The players spent 10 days in February and most of March on Catalina Island. Cheeves was hobbled with a leg or foot injury, but was ready for action when exhibition games with Vernon of the Pacific Coast League started. He was used in relief during the series.

The Cubs broke camp and played games in California against other PCL clubs and then headed cross-country, making stops along the way. Cheeves was given starting assignments and pitched a complete game, 11-1 win over Wichita on April 6 to show he was ready for the season. He lost his first start, in Cincinnati, but beat the Reds and Eppa Rixey when they had a rematch in Chicago on April 21. A first-inning shelling by the Cardinals in his next start sent Cheeves to the bullpen for a couple of weeks.

Killefer brought Cheeves out of the pen when the Giants came to town on May 13. Cheeves continued his mastery of the Giants with a 3-0 win. His control was off (six walks), but he scattered seven hits. Killefer brought him back three days later for the series finale. This time Cheeves allowed six hits and two runs, but triumphed, 3-2, to help the Cubs split the four-game series. Cheeves credited his knuckleball for his success against the Giants. He had six more decisions against the Giants that year – but five were losses and his killer mystique was gone.

After a pounding by the Giants in early August, Cheeves was relegated to the bullpen. He started games only when doubleheaders piled up and forced Killefer to use an extra arm. That was the case in the first game of a September 22 twin bill in Philadelphia. In the midst of four doubleheaders in as many days, Cheeves went all 11 innings in a 7-5 win. He closed out the year at 12-11 with a 4.07 ERA. The team finished in fifth place.

Cheeves was an early arrival on Catalina again in 1923. Optimism was high as the Cubs felt they could contend after four seasons in the second division. Writer Hugh Fullerton enthusiastically predicted that “Cheeves is ripe” and would certainly win 60 percent of his starts.12He was way off the mark – an elbow injury restricted Cheeves to only eight starts, none of which he won. The Cubs finished fourth, but Cheeves was only 3-4 with a 6.18 ERA. On November 10 he was sold to Wichita Falls in the Class A Texas League.

The announcement of his release in the Chicago Tribune was one of the few times Cheeves’s nickname of “Chief” appeared in print.13 As with many Native Americans before and after him, he was given the ethnic moniker. Some players objected to nicknames hung on them. Cheeves was quite the opposite and included “Chief” as part of his signature on his Hall of Fame questionnaire.

Despite the sale to Wichita Falls, Cheeves’s name was included in numerous news stories about a pending Cubs-Cardinals swap. The premise was that Charlie Hollocher wanted to get closer to home. The Cubs were supposedly offering Hollocher, cash, and others for Rogers Hornsby. Nothing materialized; it took four more years for the Cubs to snag Hornsby.

Cheeves worked as a starter and reliever for the Spudders in 1924. Following a 4-1 loss to Shreveport on June 13, his record stood at 2-1 with an 8.36 ERA in six appearances. Even so, the Cleveland Indians saw something they liked and purchased him on June 16. The Indians also sent pitcher Logan Drake as part of the deal.14

The Tribe started Cheeves against the Tigers in Detroit on June 22. Cleveland took a 1-0 lead, but he walked two and gave up two hits to start the second inning. Given a quick hook by manager Tris Speaker, he was replaced by Dewey Metivier, who allowed two sacrifice flies and a 4-1 lead. “Metivier, who pitches one good game a season,” settled down and earned a 7-5 victory with eight innings of work.15

Cheeves appeared in seven more games, all as a reliever and all Cleveland losses. In his eight games he hurled 17 innings with no decisions and a 7.79 ERA. After nearly three weeks of inactivity he was released to Kansas City of the American Association. The Blues were in last place and Cheeves did little to change that status. He was used in three games, all against the Minneapolis Millers. On August 26 the Blues won 11-6 in his start. His next two starts resulted in losses of 11-7 and 14-4.

Plans were for Cheeves to rejoin Cleveland in spring training in 1925. But on February 14, he and outfielder Tom Gulley were released to Little Rock of the Southern Association. By mid- April he had not reported to Little Rock. This led to a series of unflattering articles about Cheeves’s attitude. His conditioning was always an issue, but it was especially bad while at Cleveland. He also had something of a stubborn streak and did not follow the advice of coaches and other mentors. Coupled with an arm that had lost some zip, this made many feel he had squandered his talent.16

Cheeves may well have known his arm was not ready for use in February and March, which would explain his failure to show at Little Rock’s training camp. In June he signed with Meinert’s Gymnasium Club, of Dallas. Meinert’s was one of the better semipro teams in North Texas.17 How Cheeves fared is unknown, but his arm must have responded because he was back in the professional ranks in 1926 with the Terrell Terrors of the Class D Texas Association.

Cheeves’s younger brother David had a tryout with the San Antonio Bears and was released. He signed with Terrell, managed by old friend Curley Maloney, and persuaded Virgil to join. Virgil debuted in late June and dropped his first four decisions. He finally got into the win column with a victory over Austin on July 25 and closed out the season with a 5-4 record in 12 games.

Maloney served as a scout for John McGraw and the Giants, whom Cheeves joined at their training camp in Sarasota, Florida in February 1927. Cheeves looked strong at the start of camp, but after a pounding on March 28 by the St. Louis Browns, his status was cloudy. Still, he earned a regular-season roster spot and in his first appearance went three innings against the Phillies in a 9-6 loss. He relieved in two more losses in May.

On May 21 New York sold Cheeves and Jack Bentley to the Newark Bears of the International League. Cheeves provided minimal support to the success of the third-place team in his 14 appearances. He had a 3-6 record and a 6.05 ERA.

Nevertheless, the Giants invited Cheeves to spring training in 1928. He reported at 212 pounds and showed little desire to lose weight or work hard. He was quickly released. Returning to Texas, Cheeves played semipro ball and had a brief stint with the Midland Colts in the West Texas League. The Colts were managed by Maloney, who used Cheeves in four games before cutting him loose with an 0-3 mark.18 His best move of the year came when he married Lilly Elizabeth Durham.

Manager Del Pratt of the Waco Cubs (Texas League) invited Cheeves to a tryout in 1929. He made the team and debuted on April 20 with a superb 9-1 win over San Antonio. He won three of his first four decisions.19 He unraveled after that – his record dropped to 3-8 before he was released. Cheeves was back in the semipro ranks by the end of June. He also branched out into construction rather than just carpentry.

Lilly contracted tuberculosis and the family moved to Colorado. (The couple had a daughter, JoAnn Elizabeth, born on August 14, 1931.) Over a ten-year period, they lived in Sanford, Alamosa, and Colorado Springs. Cheeves played baseball in the first two towns, mainly at first base. For a few years he worked as a house painter until finding government work.

The 1940 census lists the family in Alamosa, where Cheeves worked as a timekeeper for the WPA, the federal government’s work program. Lilly passed away in 1945 in Colorado Springs and Cheeves returned to the Dallas area, where he continued to work as a painter.

Cheeves took his nephew, Don Linebarger, under his wing and taught him the art of pitching (including a knuckle-curve rather than a knuckleball).20 Virgil was remarried in 1963, to Allie Dillard Cox, an older widow. She died on September 17, 1973. Cheeves retired, but still worked as a seasonal employee (painter) for the Dallas school system. He died of congestive heart failure at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas on May 8, 1979, and was buried beside Lilly in Laurel Land Memorial Park in Dallas.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and Rory Costello and fact-checked by David Kritzler.

In July 2018, I was contacted by SABR member Don Linebarger, the nephew of Virgil Cheeves. Don has done extensive research about all the brothers. We spent a day going through all the articles he had accumulated. He also provided me with family insights that were otherwise lacking. His help made it possible to paint a clearer, more detailed story of Virgil’s career and family life.

Revised version posted on DATE.

Notes

1 Evers had also served as the Cubs’ player-manager in 1913.

2 ‘Chicago Cubs Have Wizard Kid Pitcher,” Oakland Tribune, January 2, 1921: 8.

3 Ibid.

4 High-school information from Cheeves’s Hall of Fame questionnaire. Oak Cliff HS was also mentioned in newspapers during his semipro days.

5 Horace B. McCoy, “The Tale of Virgil Cheeves, Who Went from an Oak Cliff Grocery to Major Leagues in Two Years,” Dallas Times-Herald, July 15, 1921: page unknown.

6 “Eastland 9 Mineral Wells 3,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, May 1, 1920: 3.

7 McCoy, Ibid.

8 “Pirates Find Vaughn Who Can’t Find Arm,” Chicago Tribune, September 8, 1920: 24.

9 “Big Change in Evers, Comes With Year,” The Sporting News, March 10, 1921: 1.

10 Cheeves mentioned the knuckler twice on his Hall of Fame questionnaire.

11 James Crusinberry, “Cheeves Balks Moran As Cubs Clout Pill, 6-2,” Chicago Tribune, June 26: A2.

12 Hugh Fullerton, “Cubs, First Division Club, May Finish Near the Top,” Chicago Tribune, March 16, 1923: 17.

13 “Chief Cheeves Draws Trip to Wichita Fall,” Chicago Tribune, November 28, 1923: 15.

14 “Cheeves, Ex-Cubs Hurler, Is Sold to Cleveland,” Chicago Tribune, June 17, 1924: 25.

15 Harry Bullion, “Dauss Weakens in Closing Innings and Cleveland Takes Final Game, 7-5,” Detroit Free Press, June 23, 1924: 12.

16 “Virgil Cheeves’ Case Is a Good Lesson to Youth,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 10, 1925: 24.

17 “Meinert’s Team Will Play Denison Squad,” Dallas Morning News, June 11, 1925: 19.

18 Statistics courtesy of Raymond Nemec’s research on the West Texas League.

19 “Cheeves and Glazner Take Slab Saturday,” Dallas Morning News, May 4, 1929: 19.

20 Interview with Don Linebarger, July 18, 2018.

Full Name

Virgil Earl Cheeves

Born

February 12, 1901 at Oklahoma City, OK (USA)

Died

May 5, 1979 at Dallas, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.