Walter Schlichter

From 1902 through 1911, Walter Schlichter owned the Philadelphia Giants, the finest African American team of the era. Schlichter was white, the Philadelphia Item’s sporting editor, and had previously managed boxers, not ballplayers. Yet with Sol White he formed a persevering, successful partnership. Competition, alignment with more powerful forces, an ill-advised secondary baseball venture, and finally a break with White spelled the end of the Giants’ predominance. Schlichter returned to sports writing, where he played a critical (albeit anonymous) role in breaking the Black Sox Scandal.

Henry Walter Schlichter was born on March 1, 1866, in Philadelphia. His parents, Henry and Tamson (née Bridenbach) Schlichter, were of established German American stock. Census records suggest several siblings; his brother Elmer later joined him on the Item’s sports writing staff. His father worked as a hotelkeeper.1

After a sickly childhood, Schlichter joined Philadelphia’s Schuylkill Navy Athletic Club as a young adult. In 1889 he won the Club’s cross-country race. In 1890, in the ring, he was runner-up in the Mid-Atlantic A.A.U. bantamweight class. Schlichter also joined the Item that year, where he soon became the sporting editor.2

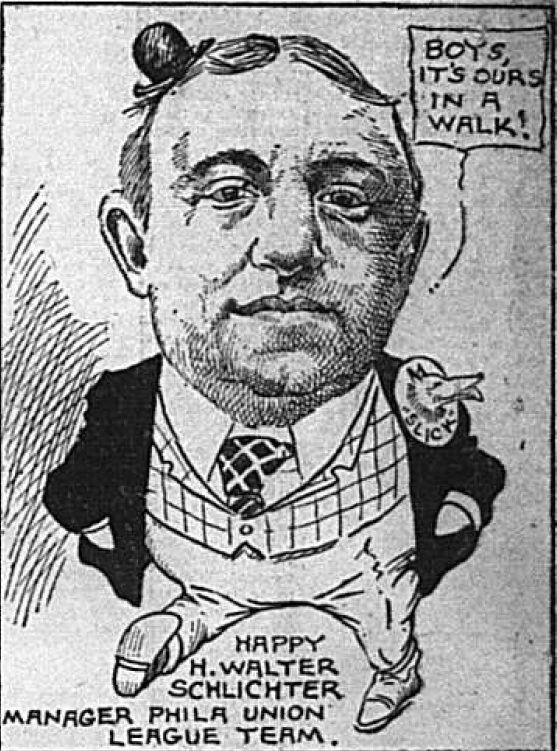

Known throughout Philadelphia’s athletic community as “Slick,” he sponsored football clubs, organized swim meets, announced track and field events, and oversaw cyclist competitions. But his heart belonged to boxing, a sport transitioning from its brawling, bare-knuckled past to a commercialized, gloved future.3 Schlichter’s active days as “a hard, scientific puncher” soon faded; but by the end of the decade, he was established as a “referee of recognized ability” and a “popular manager of boxing affairs.”4

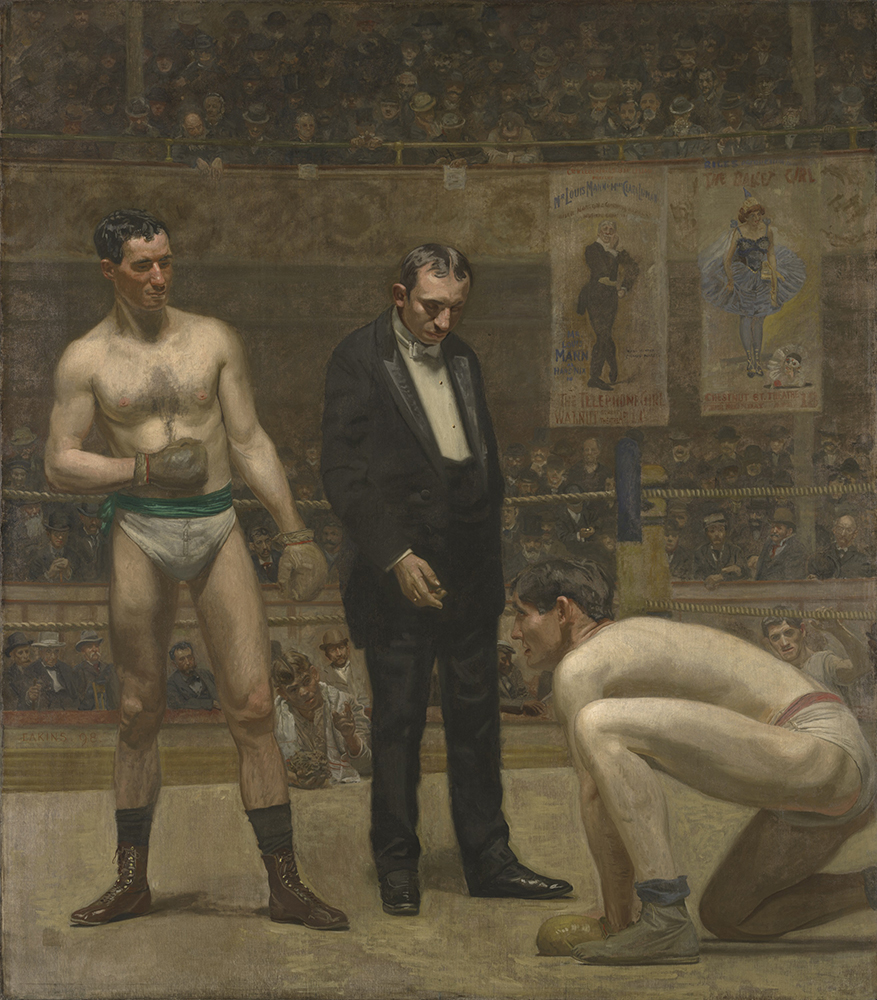

In February 1898 he married Mary McAllister. Soon afterwards, his friend Thomas Eakins presented the bride with a portrait, Maybelle. Schlichter occasionally took Eakins to local fights and, on April 29, 1898, the painter witnessed his friend referee a bout between Charley McKeever and Jack Daly. Afterwards Eakins posed the three principals separately in his studio. The resulting work, Taking the Count, remains a masterful depiction of American sporting life. In its serene depiction of a violent bout, Schlichter occupies the center of the painting, attentive only to the fallen and dazed Daly.5

Schlichter seemed poised to emerge as a leading force in boxing. He managed Philadelphian Martin Judge, who gallantly but unsuccessfully fought Baltimorean Joe Gans three times in 1899. In January 1902, for the Penn Athletic Club he managed, Schlichter arranged a February fight between lightweight champion Frank Erne and Gans.6 Yet New York promoters squeezed him out of his Club role, and Erne backed out of the fight.7 The reset Erne-Gans showdown, sans Schlichter, occurred that May in Ontario. Gans KO’d Erne to become the first African American boxing champion.

On October 28, 1901, the Item reported that a “new colored base ball team … has been organized with headquarters in Philadelphia” and that these “Giants will be under the captaincy and management of Sol White.”8 This was only the latest iteration of an established brand. A black Giants baseball club played intermittently in Philadelphia in the 1880s and 1890s.9 In July 1901 Gans briefly operated a Philadelphia Giants squad in Baltimore.10

On the Giants re-emergence, White wrote in 1907 that “Harry Smith, base ball writer of the [African American] Philadelphia Tribune, conceived the idea of a professional team to represent Philadelphia.”11 Smith and Schlichter likely were well acquainted professionally, and the former may have pitched the idea (possibly referring to Gans’s team) to the latter. Smith also may have recommended White to Schlichter. Yet, while Smith was occasionally listed as the Giants’ assistant manager and likely used the Tribune to market the team, his specific role is unclear.12

White also later wrote of Schlichter arranging a September 30, 1901, exhibition game between the Cuban X-Giants and the Philadelphia Athletics at the latter’s Columbia Park.13 The Item significantly promoted the match beforehand.14 While only 1,670 attended the game, which ended in a 4-4 tie after 11 innings, the mostly African American crowd was notably enthusiastic.15 The match, White maintained, drove Schlichter’s ambitions to organize a black team.

Schlichter’s boxing background served him well in independent baseball. He knew how to schedule, negotiate cash guarantees and gate shares, sustain a network, and practice publicity. Moreover, while racism was plentiful in boxing, its color line was not as pronounced as baseball’s. Schlichter and black boxers developed lasting professional relationships; Gans, for example, would write letters to Schlichter on his upcoming bouts to be published in the Item.16

White not only managed, captained, and played, but also scouted and determined the roster as a general manager would. He also aided with business management. Schlichter only occasionally accompanied the team on the road, leaving White to serve as “travelling secretary and sometimes booker.”17

The era’s racism determined that a white owner had greater access to capital resources and other white power brokers. Yet throughout baseball history many a successful owner has granted a talented general manager free rein. The relationship between Schlichter and White was grounded in mutual respect. “Sol White was one of the brainiest baseball players and managers that ever put on a spiked shoe,” the owner later stated.18 Schlichter “was as shrewd as you make ’em,” the player-manager-GM later observed.19

White played with the Cuban X-Giants (often called the “Cubes” by contemporaries) for most of the previous half-dozen seasons. He signed many of their stars for the Philadelphia Giants (similarly referred to as the “Phillies”) reboot: pitchers Charles “Kid” Carter and William Bell, catcher Clarence Williams, third baseman Johnny Hill, and second baseman Frank Grant. White also uncovered outfielder Andrew “Jap” Payne, the first of many notable youngsters who made their professional debut with the Phillies.20

The Phillies walloped Camden City, 12-4, on April 23 to begin the 1902 campaign.21 By September 8, the squad possessed a 70-33-2 record.22 But Schlichter could not entice Cubes owner Ed Lamar to a series between their teams. Instead, the Cubes enticed Williams and Hill to jump back.23 “Financially it was bust,” White later wrote of the Phillies’ debut season, claiming both he and Schlichter lost money. “Otherwise it was a grand success.”24

That offseason Schlichter and White abandoned the “cooperative” payment plan, where “dividends” were distributed to players, on an often uneven basis, based on owner-determined profits. Instead, as White later recalled, “We copied a big league contract which called for a ten day notice of release and salaries the first and fifteenth of every month.”25 These salaries ranged from $60 to $90 per month in 1903.26 White took considerable pride in this pay structure’s implementation; it likely proved a selling point in his recruiting.

Players, once recruited, needed to be retained. To this end, Schlichter enrolled the Phillies into the first of a dizzying sequence of leagues they would join in the coming years: the newly formed National League of Independent Base Ball Clubs. The purpose of the NLIBC, the Item asserted, was “to prevent players from jumping their contracts.”27 Lamar also brought the Cubes into this fold. Yet Lamar could not re-sign infielder Bill Monroe, who instead penned a Phillies contract in March 1903.28 When Monroe, angered by a club-imposed discipline, attempted to jump back to the Cubes that July, Lamar honored the league’s tenets (lest other NLIBC teams would not play his) and rebuffed him.29

But, more than anything else, better gates allowed the Phillies to turn the corner. In 1902 they apparently played only two games in the New York City market, where the ability of independent teams (black or white) to skirt laws prohibiting Sunday baseball made for lucrative opportunities. Both these matches were against Nat Strong’s Murray Hills squad.30 Soon labeled “the Napoleon of semi-professional baseball,” for his aggressive hold on the region’s independent ball, Strong became infamous for extracting 10% of the gate for any game he booked and underpaying black teams.31

In 1903 the Phillies played at least ten games in the New York metropolitan area against white teams. These appearances began with a wild Sunday victory, 16-12, over Ridgewood on April 19 with 10,000 in the stands.32 Two Sundays later against Hoboken, in front of 6,000, they faced semipro ace Ernie Lindemann for first time. Behind Carter, Philadelphia triumphed, 7-3.33 They also cracked the Atlantic City resort market with three summertime appearances.34

The Phillies impressed onlookers: “as fine a semi-professional team as there is in the country” and “in big league class.” All that awaited was a showdown with the Cubes.35 Schlichter announced the details in July: a seven-game series that September, with “a substantial side bet” between him and Lamar, and an agreement that “the winning team will take 60 per cent. of the gross receipts and the losers 40 per cent.”36 With Monroe injured, and the Phillies unable to solve Andrew “Rube” Foster’s pitching, the Cubes took the series.

As the 1903 season wound down, Schlichter filed articles of incorporation for the Philadelphia Giants Base Ball and Athletic Association in Washington, DC. With himself as president, capital stock was listed at $20,000. The incorporation papers were notarized in Pennsylvania on April 25, 1904.37

By that time, rookie outfielder Pete Hill and Foster — whom White signed, and whom the NLIBC subsequently awarded to Philadelphia after Lamar submitted his own claim — had joined the team.38 That July, three Phillies threw no-hitters: Kid Carter versus Atlantic City on July 9, Will Horn against Oxford (Pennsylvania) on July 12, and Foster versus Trenton Y.M.C.A on July 25.39 In September, the Phillies avenged themselves on the Cubes, taking a three-game series.

Schlichter likely was not free of his era’s prejudices. The Item occasionally printed racist caricatures of black athletes that, as sporting editor, he probably could have disapproved.40 Yet, in at least one instance, Schlichter objected to advancing Jim Crow norms. In 1903 he refused to pay a hotelkeeper a fee after the proprietor forced the Phillies to change in a stable rather than in the hotel.41 After the 1904 season, he lobbied the independent Tri-State League to accept the Phillies. But the color line held. “It was admitted that the Philadelphia aggregation was a good drawing card,” a Harrisburg reported noted, “but it was thought best that they be kept out of the League.”42

In 1905 the Phillies, White later stated, fielded “one of the greatest line-ups that ever composed a colored baseball team.”43 Lefty Dan McClellan and teenaged Emmett Bowman joined the pitching staff and, with Rube Foster, formed a trio of 30-game winners. Veteran Grant “Home Run” Johnson arrived, and indeed led the squad with 12 homers. Frank Grant, Pete Hill, and Bill Monroe all contributed memorable campaigns. The Phillies finished the season with a 128-23-3 record.44

As another Cubes/Phillies showdown loomed that summer, Lamar offered a customary 60/40 split. Yet the Item reported, “Inasmuch as the Champions insist upon the winner taking all the receipts, it is hardly likely the series will be arranged.”45 Instead the Phillies toyed with the Strong-aligned Brooklyn Royal Giants all season, compiling an 11-0-1 record against the “Royals.”46 Lamar, unable to book Brooklyn either, accused Schlichter and Strong of collusion.47

By now called a “trust,” Schlichter and Strong formed a booking agency in early 1906, announcing they would schedule all games for the Phillies, Royals, All-Cubans, and several white independents.48 In practice, it seems Strong increasingly arranged the Phillies’ weekend matches in the New York market, leaving less profitable games to Schlichter.49

A competitive reaction promptly emerged — the Philadelphia Quaker Giants, incorporated by brothers Jess and Eddie McMahon in February 1906.50 By March the “Quakers” had raided the Phillies of Rube Foster, Home Run Johnson, and Bill Monroe.51 Schlichter sought an injunction, claiming the new club’s name was not sufficiently distinctive.52 That effort failed, but he and Strong corralled Foster and Johnson. The pitcher returned to the Phillies by mid-April. The slugger became Brooklyn’s player/manager, helping to close the chasm between the Phillies and Royals.

The infielder was another matter. A charismatic star, renowned both for his play and for his crowd-pleasing performances in the coaching box, Monroe was central to a team’s marketing. He rejoined the Phillies but, as they journeyed to Brooklyn to play the Brightons on April 1, fellow passenger Jess McMahon again recruited him for the Quakers. Monroe told Schlichter. Schlichter told Monroe he could not let the Brightons’ manager down and handed him $125 to play that afternoon.53 Monroe homered as the Phillies pounded Snake Wiltse for 15 hits, and won, 10-4.54

After the game, Schlichter stated that he heard “mutterings” from other Phillies who were “‘sore’ that any one player could command so much more than the others.” Consequently, Schlichter “told Monroe that he would have to return the $125 and allow it to be distributed among the other players or that he could consider himself suspended.”55 Monroe joined the Quakers.

Meanwhile, the International League of Independent Base Ball Clubs formed in early April. Its members were the Cubes, Quakers, Cuban Stars, Havana Stars, and Philadelphia Professionals.56 With two seeming Schlichter/Strong foes onboard, Lamar and the McMahons, this circuit may have begun as a competing force. But after the Quakers failed to play scheduled games, the league dismissed them in July and recruited the Phillies to take their place.57 The Quakers soon disbanded. The Phillies eventually finished on the top of International League standings and outpaced all other eastern black independents. Despite this success, Schlichter stated that the Phillies lost $3,000 in 1906 due to the costly salary war initiated by the McMahons.58

To address such non-profitable turbulence, yet another circuit was created on October 29, 1906: the National Association of Colored Base Ball Clubs. The Phillies, Royals, Cubes, Cuban Giants, and Cuban Stars comprised the new enterprise. Schlichter was elected president, Nat Strong secretary.59 “The organization,” Schlichter wrote in January 1907, “was not formed for the purpose of reducing the players’ salaries nor for the purpose of placing them on the basis of slaves.”60 Yet, in the same column, Schlichter stated the owners agreed to cap salaries at $100 a month, making it clear that the National Association was an economic cartel formed to prevent players from freely negotiating salaries.61

With some empathy, Foster later wrote that “Schlichter broke himself” running an independent black baseball team.62 But when Schlichter cut salaries for certain Phillies after the 1906 campaign, capped meal allowances, and forced players to provide their own uniforms, Foster took a critical step becoming a magnate himself. “He called several of the players of the Philadelphia Giants together and told them, while his contract or salary had not been reduced, he did not think they were being treated fairly, and they were going to starve trying to better themselves, adding that he would guarantee their salaries offered by Philly management, and place a team in Chicago,” an interviewer later wrote.63 Foster, along with Phillie infielders Nate Harris and Harry Moore, joined that city’s Leland Giants.

In 1907 White authored, and Schlichter edited and published, Sol White’s Official Base Ball Guide, a landmark black baseball book. White also reloaded with two talented youngsters that season: shortstop John Henry Lloyd and catcher Bruce Petway. According to a Jersey City correspondent, the Phillies proved “the strongest team on the independent circuit” and rolled to the initial National Association crown.64 After the season, Pete Hill and several other Phillies left for Cuba to continue their baseball livelihoods. Meanwhile, Schlichter rubbed shoulders with major-league magnates at the National League meetings, “looking for ‘protection’ for his colored stars.”65 When Hill returned, he joined Foster in Chicago.

Throughout the Phillies’ glory years, Schlichter continued as the Item’s sporting editor. A sensationalistic evening paper, it claimed over 200,000 readers.66 Slick remained a regional boxing fixture. He assisted in organizing Philadelphia’s auto show and soon helped to launch its runners’ marathon.67

In December 1907, the (white) Union League of Professional Base Ball Clubs of America was launched.68 Its founder was Alfred Lawson, former major-leaguer and future visionary (or con man, depending on one’s perspective). Lawson was also elected the circuit’s president.69 Schlichter backed its Philadelphia team, which he would also manage.

Lawson claimed the enterprise was “organized on a basis which makes it as strong as the Rock of Gibraltar,” and that it would content itself “merely to do business on an independent scale” instead of poaching contracted players from organized baseball.70 Schlichter incorporated his Unions club, heavily promoted it within the Item, and oversaw construction of its West Philadelphia grounds.71

Yet the Union League had been launched in a recession, and its talent-poor product failed to attract fans. Schlichter quickly sought to ease out of managing. On May 20, with a record of 6-14, he handed the reins to Ernest Landgraf.72 Two weeks later the league collapsed.73 Lawson filed for bankruptcy on June 26.74

Yet the Union League had been launched in a recession, and its talent-poor product failed to attract fans. Schlichter quickly sought to ease out of managing. On May 20, with a record of 6-14, he handed the reins to Ernest Landgraf.72 Two weeks later the league collapsed.73 Lawson filed for bankruptcy on June 26.74

“July 15, 1908, we left Philadelphia for a western trip, with players’ salaries a half month in arrears,” Sol White recalled.75 Although the team was paid in full for July on August 1, it was “the first time,” he added, that “the Philadelphia Giants failed to meet its obligations to players on the first of the month or any other pay day.”76 During the road trip, the Phillies battled the Lelands to a draw in a six-game series. Afterwards, Emmett Bowman stayed behind to join Foster’s team.77 By September, the team returned home, playing games at the otherwise vacant Union League Park.78 The Phillies fell short of the Royals in the National Association race, their run of four straight championships over.

Following the campaign, Schlichter and White split. White revived the Philadelphia Quaker Giants.79 Schlichter promptly ensured that White’s Quakers would be ignored by the International League of Colored Baseball Clubs of America and Cuba (the National Association’s successor).80 Ray Wilson took over the Phillies’ field operations. With veterans like Dan McClellan and Wilson, and youngsters like John Henry Lloyd, Bruce Petway, Frank Duncan, and Spottswood Poles, the team remained formidable. In August, they took two of three against the Lelands.81 Yet, as a Binghamton correspondent opined, “The Philadelphia Giants are not in the same class as ball players as either the Brooklyn Royal Giants or the Cuban Giants and lacking the fun” those teams provided crowds.82 Notices of Phillies open dates appeared in the Item, and the team eventually finished well out of the 1909 International League pennant race.83 That offseason, Lloyd, Duncan, and Petway joined the Lelands.

Schlichter lifted the ban on Sol White in early 1910 so he could manage the Royals. In the following years, the two enjoyed a warm correspondence. In 1936 the former owner mused to his former field general: “It is true I might have ‘made a million’ or less had I stuck to colored base ball but I doubt it. Outside of Nat Strong I know of no one who has. And, at that, I am better off than he is right now. I am still living and have my health and Nat didn’t take his wealth him. There is no pocket in a shroud, you know.”84

The Phillies continued for another two seasons with marginal success and erratic fan support. Two young stars — catcher Louis Santop and pitcher Dick Redding — suddenly defected in July 1911. Schlichter disbanded the team on August 1.85 Five days later, in Queens, a quickly reconfigured edition was manhandled by the Strong-controlled Cypress Hills, 15-10.86 For the next two years, likely operated exclusively by Strong, the Phillies apparently existed only in weekend appearances against his New York market teams.

Mary Schlichter died in 1913. By that time, Walter no longer managed fights, but instead dabbled in vaudeville. It’s likely that he met his second wife, actress Margaret Grayce, through the stage.87 He remained a Philadelphia sportswriter, still focused upon boxing. Sometime before the Item folded in 1915, Schlichter joined the Record. He then landed at the North American — where he played a pivotal role in unmasking the Black Sox scandal.

This tale began early in the century, when Schlichter managed fight cards on which boxer Billy Maharg appeared.88 Years later, Maharg was one of several principals who met with seven White Sox players immediately before the 1919 World Series and arranged a fix. By late September 1920 — fueled by lingering suspicions and concerns over gambling’s influences — a grand jury was convened in Chicago to investigate the 1919 World Series.89 Its proceedings were brazenly open to, and reported by, the press.

At some point, likely as these headlines spilled out, Maharg met with Schlichter.90 Maharg may have been motivated by the $10,000 reward Sox owner Charles Comiskey offered for evidence regarding his players’ participation in throwing the World Series.91 After hearing Maharg’s story, Schlichter informed his colleague (and North American sporting editor) James Isaminger. On September 27, Isaminger interviewed Maharg himself, and the next day his story headlined the North American’s front page. Schlichter’s role was unmentioned within.92

By that point, no one else directly involved with the fix had publicly come forward with details. The grand jury in Chicago had decided not to call any of the players associated with the scandal; the White Sox were trying to overtake the Indians for a second straight pennant. But within 24 hours of Isaminger’s exposé, Eddie Cicotte and Joe Jackson confessed, and the grand jury issued indictments.93

Schlichter, after the Black Sox scandal, continued with the North American until it folded in 1925. The Inquirer then hired him. By 1941, although his output had been sporadic for years, he was heralded as “the oldest sportswriter in America.”94

On January 15, 1944, Walter Schlichter died of pneumonia in Philadelphia. Margaret had died in 1942. Neither of his marriages produced any children. He was buried nearby in Bala Cynwyd’s West Laurel Hill Cemetery. For the first time, in his Inquirer obituary, Schlichter’s role in the Black Sox scandal was detailed. It was, the writer suggested, “the highlight of his career.”95 His ownership of one of Philadelphia’s greatest baseball teams was mentioned only in passing.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Chris Rainey. Thanks also to Jacob Pomrenke for his insights on the Black Sox.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed the following:

Hogan, Lawrence D. Shades of Glory: The Negro Leagues and the Story of African-American Baseball (Washington: National Geographic, 2006).

Lanctot, Neil. Fair Dealing and Clean Playing: The Hilldale Club and the Development of Black Professional Baseball, 1910-1932 (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2007).

Lester, Larry. Rube Foster in his Time: On the Field and in the Papers with Black Baseball’s Greatest Visionary(Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2004).

Lomax, Michael E. Black Baseball Entrepreneurs, 1902-1931: The Negro National and Eastern Colored Leagues(Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2014).

Riley, James. The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf, 1994).

dbs.ohiohistory.org/africanam/html/nwspaper/advocate.html

https://seamheads.com/blog/category/negro-lgs/

Notes

1 This background per the death certificate, census records, and family trees available through Ancestry.com

2 On this background see the comments of noted bantamweight William Campbell within Hotspur [pseud.], “Winter Sports of All Sorts,” Buffalo Enquirer, January 17, 1902: 4.

3 For this transition, see Elliott J. Gorn, The Manly Art: Bare-Knuckle Prize Fighting in America (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1986), 207-247.

4 “Spirited Boxing at the Academy,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 29, 1892: 3; “Fistic Authority,” Buffalo Courier, July 3, 1899: 3; Sporting Miscellany, Buffalo Commercial, April 5, 1899: 6.

5 For a study of Taking the Count, see Carl S. Smith, “The Boxing Paintings of Thomas Eakins,” Prospects, Vol. 4 (October 1979): 403-419. For a contemporary depiction of the fight, see “M’Keever Bests Clever Jack Daly,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 30, 1898. For background on Maybelle, see Lloyd Goodrich, Thomas Eakins: His Life and Work (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1933), available online at https://tinyurl.com/qu6tj35.

6 Hotspur [pseud.], “Winter Sports of All Sorts,” Buffalo Enquirer, January 16, 1902: 4.

7 “New Yorkers Not Wanted,” Pittsburgh Press, January 26, 1902: 19; “’Erne Did Right!’” Buffalo Express, February 12, 1902: 11.

8 “Base-Ball,” Philadelphia Item, October 28, 1901: 8.

9 James E. Brunson III, Black Baseball 1858-1900, Volume 1 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2019), 222.

10 “Sporting Miscellany,” Baltimore Sun, July 17, 1901: 6; “Gans’ Nine Defeated 17 to 5,” Baltimore Sun, July 19, 1901: 6.

11 Sol White, Sol White’s Official Base Ball Guide (South Orange, NJ, Summer Game Books, 2014): 35.

12 Tribune archives, prior to 1912, do not exist, leaving Smith as an unfortunate cipher in the Philadelphia Giants’ history. Note, also, there were two Harry Smiths with the Giants in 1902. In addition to the sportswriter, there was a first baseman with the same name. For a brief bio of the player, see “Base-Ball,” Philadelphia Item, December 29, 1901: 7.

13 Sol White, “Sol White Says,” Cleveland Advocate, June 14, 1919: 6; Sol White, “Sol White Says,” Cleveland Advocate, June 21, 1919: 7.

14 The Item mentioned the game in its sporting section on September 21st, 23rd, 25th, and 30th.

15 “Base-Ball,” Philadelphia Item, October 1, 1901: 8. For fuller accounts see; “Athletics Play a Draw with Cubans,” Philadelphia North American, October 1, 1901: 10; “Cuban X-Giants Tie Athletics,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 1, 1901: 6. Note only five of the “Athletics” playing that day were with Connie Mack’s team during the 1901 season; several came from other American League squads, and pitcher Davey Dunkle from the Eastern League.

16 Gans would also operate a Baltimore Giants squad. See “Baseball Gossip,” Washington Post, August 18, 1905: 16.

17 Sol White, “Sol White Recalls,” New York Age, January 10, 1931: 6.

18 “Baseball Stars of the Past,” New York Age, August 5, 1939: 8.

19 Sol White, “Sol White Recalls,” New York Age, January 3, 1931: 6.

20 For more on the 1902 Giants roster, see “Base-Ball,” Philadelphia Item, May 22, 1902: 8.

21 “Base-Ball,” Philadelphia Item, April 24, 1902: 7.

22 “Gossip of the Future Greats,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 8, 1902: 10.

23 “Diamond Dust,” Wilmington Republican, June 6, 1902: 2; “Lost Ball in the High Winds,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 4, 1902: 3.

24 Sol White, “Sol Corrects W. Rollo Wilson,” New York Amsterdam News, March 27, 1929: 15.

25 Sol White, “Sol White Recalls,” New York Age, January 3, 1931: 6.

26 Floyd J. Calvin, “Sol White Recalls Baseball’s Greatest Days,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 12, 1927: 16.

27 “Base-Ball,” Philadelphia Item, February 20, 1903: 8.

28 “Base-Ball,” Philadelphia Item, March 4, 1903: 8.

29 “Monroe Has Returned,” Harrisburg Telegraph, July 16, 1903: 1.

30 See the results and remaining schedule within “Base-Ball,” Philadelphia Item, August 8, 1902: 8.

31 “Strong Welcomes War with Hussey,” Brooklyn Citizen, March 15, 1907: 5.

32 “Wants and Doings of the Ball Tossers,” Brooklyn Standard Union, April 20, 1903: 9.

33 “Base-Ball,” Philadelphia Item, May 4, 1903: 8.

34 See the results and remaining schedule within “Base-Ball,” Philadelphia Item, August 18, 1903: 8.

35 “Philadelphia Giants Beat Murrays Again,” New York Evening World, July 20, 1903; Harrisburg Star-Independent, July 17, 1903: 6.

36 “Base-Ball,” Philadelphia Item, July 19, 1903: 8.

37 “Charters Granted Under District Laws,” Washington Times, September 28, 1903: 10; The Colored American (Washington DC), May 7, 1904: 9.

38 “Camden Awarded Pitcher Polhock,” Altoona Times, April 5, 1904: 5.

39 “Base-Ball News,” Philadelphia Item, July 10, 1904: 8, “Base-Ball,” Philadelphia Item, July 13, 1904: 8, “Base-Ball,” Philadelphia Item, July 26, 1904: 8.

40 See, for example, the Item’s September 1, 1906, and September 13, 1908, sporting pages.

41 “Ball Players Treated Unfairly,” Harrisburg Telegraph, July 22, 1903: 6.

42 “Tri-State Ball Again Assured,” Harrisburg Telegraph, December 17, 1904: 12.

43 Sol White, “Sol White Recalls,” New York Age, January 3, 1931: 6.

44 For team record and individual statistics, see Phil S. Dixon, Phil Dixon’s American Baseball Chronicles — Great Teams: The 1905 Philadelphia Giants Volume III (Xlibris, 2010).

45 Philadelphia Item, August 4, 1905: 8.

46 For an example of the Royals identified as being under Strong’s business management, see “‘Big Bill’ Smith with Royal Giants,” Brooklyn Standard Union, February 27, 1905: 3. For the Phillies’ record versus the Royals, see Phil S. Dixon, Phil Dixon’s American Baseball Chronicles — Great Teams: The 1905 Philadelphia Giants Volume III (Xlibris, 2010): 277-290.

47 “Amateur Baseball,” Brooklyn Standard Union, September 22, 1905: 9.

48 “Rube Foster Jumps to the Philadelphia Giants,” Brooklyn Standard Union, April 18, 1906: 8; “Schlichter and Strong,” Sporting Life, February 3, 1906: 9.

49 Strong is noted as the Phillies business manager for the upcoming 1906 season in “Quaker Giants Preparing for a Strenous Season,” Brooklyn Standard Union, December 8, 1905: 8. Yet this was an isolated mention of him in such a role. In 1907 he was “representing” the Phillies in the New York City region. See “With the Amateurs and Semi-Pros,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 14, 1907: 17; “Colored Y.M.C.A. Benefit,” Brooklyn Times Union, August 19, 1907: 5.

50 “New York Incorporations,” New York Times, February 11, 1906: 14.

51“Baseball Chat,” Brooklyn Weekly Chat, March 31, 1906: 12.

52 “Phila. Giant Go to Court,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 25, 1906: 67.

53 Walter Schlichter, “Slick’s Salad,” Philadelphia Item, January 29, 1907: 7.

54 “Philadelphia Giants Win,” Brooklyn Citizen, April 2, 1906: 5. The first name of pitcher Wiltse is not specified in this box score but based on his previous association with the Brightons, it is mostly likely older brother Lewis instead of younger brother George. For an example, see “Lou Wiltse’s Nose Broken,” Plainfield (New Jersey) Courier-News, October 30, 1905: 5.

55 Walter Schlichter, “Slick’s Salad,” Philadelphia Item, January 29, 1907: 7.

56 “Independents Combine,” York Dispatch, April 9, 1906: 6. For a recent overview of the League, see Gary Ashwill, “The Negro League You’ve Never Heard Of” Agate Type, January 6, 2017, https://tinyurl.com/t8v9ajc. Note this league was integrated: the Cubes and Quakers black, the Cuban Stars and Havana Stars Cuban, and the Philadelphia Professionals white.

57 “Baseball,” Philadelphia Item, July 24, 1906: 8.

58 Walter Schlichter, “Slick’s Salad,” Philadelphia Item, January 29, 1907: 7.

59 “New Baseball League Bobs Up on Horizon,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 29, 1906: 10.

60 Walter Schlichter, “Slick’s Salad,” Philadelphia Item, January 29, 1907: 7.

61 It should be noted that the NACBBC’s magnate ranks were not exclusively white. Royals owner John Connor was black, as was a de facto general manager like Sol White.

62 Andrew “Rube” Foster, “Pitfalls of Baseball,” Chicago Defender, November 29, 1919: 11. Also see Andrew “Rube” Foster, “Pitfalls of Baseball,” Chicago Defender, December 13, 1919: 11.

63 George E. Mason, “Rube Foster Chats About His Career,” Chicago Defender, February 20, 1915: 9.

64 “Phila. Giants’ Final Game in Hoboken,” Jersey Journal, October 5, 1907: 9.

65 “Baseball Magnates in Session,” Jersey Journal, December 11, 1907: 9.

66 For an example of the Item promoting its circulation, see its February 24, 1906, issue.

67 “Big Auto Show,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 21, 1902: 9; “Big Marathon Today,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 25, 1909: 8.

68 “New Outlaw Ball League Launched,” Washington Evening Star, December 17, 1907: 19.

69 For more on Lawson, see David Nemac and David Ball’s entry in Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, Volume 2 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 357-8.

70 “Baseball,” Philadelphia Item, January 12, 1908: 8.

71 “Union League Club Ready,” Brooklyn Citizen, January 24, 1908: 3; “Union Team Gets Down to Practice,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 10, 1908: 10. For an example of the Item’s publicity for the team, see the front page of the Union’s opening day of April 27, 1908.

72 “Baseball,” Philadelphia Item, May 21, 1908: 8.

73 For an assessment of its woes, see “Didn’t Even Say Goodbye,” Paterson Morning Call, May 25, 1908: 3.

74 “Baseball,” Philadelphia Item, June 27, 1908: 8.

75 Sol White, “Sol Corrects W. Rollo Wilson,” New York Amsterdam News, March 27, 1929: 15.

76 Sol White, “Sol White Recalls,” New York Age, January 10, 1931: 6.

77 “Baseball,” Philadelphia Item, August 14, 1908: 6.

78 “Baseball,” Philadelphia Item, September 20, 1908: 7.

79 Lester Walton, “In the Sporting World,” New York Age, April 8, 1909: 6.

80 For an overview, see Gary Ashwill, “The *Other* Negro League You’ve Never Heard Of: International League of Colored Baseball Clubs of America and Cuba” Agate Type, May 11, 2014, https://tinyurl.com/w4xhrv7.

81 “Philadelphia Giants Take Series,” Philadelphia Item, August 15, 1909: 8.

82 “Philadelphia Giants Easy Money for Bingoes,” Binghamton Press, April 23, 1909: 8.

83 “Giants Want Game Saturday,” Philadelphia Item, May 6, 1909: 8; “Philadelphia Giants Have Open Dates,” Philadelphia Item, June 7, 1909: 8.

84 Jerry Malloy, Sol White’s History of Colored Base Ball, With Other Documents on the Early Black Game 1886-1936 (Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, 1995): 157.

85 Lester Walton, “In the World of Sport,” New York Age, August 3, 1911: 6.

86 “Philadelphia Giants Lose to Cypress Team,” Brooklyn Standard Union, August 7, 1911: 11.

87 On these aspects of his life, see the obituaries within Philadelphia Inquirer, June 19, 1913: 7; “The Oldest Boxing Club,” Lancaster Daily Intelligencer, September 27, 1913: 6; “H. Walter Schlichter Dies; Veteran Sports Writer, Philadelphia Inquirer, January 16, 1944: 27, 30.

88 “A Fine Boxing Show,” Lancaster Morning-News, January 22, 1902: 1; “Another Boxing Show,” Lancaster New Era, February 5, 1902: 2; “The Coming Boxing Show,” Lancaster Morning-News, January 31, 1903: 1.

89 For a recent overview of the scandal, see William F. Lamb, “The Black Sox Scandal,” Society for American Baseball Research, https://sabr.org/research/black-sox-scandal-bill-lamb.

90 Baseball historian Gene Carney maintained that Maharg first called “Izzy Meyer [Isaminger], the sports editor of the Philadelphian North American.” If so, Isaminger likely requested that Schlichter conduct an initial interview with his old boxing colleague. Then, after hearing Schlichter’s report, Isaminger conducted his own interview on September 27. See Gene Carney, Burying the Black Sox: How Baseball’s Cover-Up of the 1919 World Series Fix Almost Succeeded (Washington DC: Potomac Books, 2006): 116-117.

91 On this motivation, see James C. Isaminger, “Comiskey Does Not Reply to Maharg Challenge,” Philadelphia North American, September 30, 1920: 15.

92 James A. Isaminger, “Gamblers Promised White Sox $100,000 to Lose, Philadelphia North American, September 28, 1920.

93 “Two Sox Confess; Eight Indicted; Inquiry Goes On,” Chicago Tribune, September 29, 1920: 1.

94 Bill Burk, “Sports Shorts,” Delaware County (Pennsylvania) Daily Times, June 21, 1941: 14.

95 “H. Walter Schlichter Dies; Veteran Sports Writer, Philadelphia Inquirer, January 16, 1944: 27, 30. His Black Sox role was also mentioned in Isaminger’s obituary two years later: “J.C. Isaminger Dies at Age 65,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 18, 1946: 22.

Full Name

Henry Walter Schlichter

Born

March 1, 1866 at Philadelphia, PA (US)

Died

January 15, 1944 at Philadelphia, PA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.