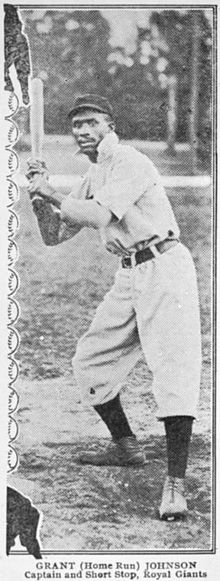

Grant “Home Run” Johnson

Grant Johnson, baseball historian Gary Ashwill argues, “was the best everyday player in Black baseball from 1895 to 1909.”1 After slugging his way to a legend with a hometown Findlay, Ohio, club in 1894, “Home Run” Johnson’s career mapped the finest Black teams of the era. He starred at shortstop for the Page Fence Giants, Chicago Columbia Giants, Cuban X Giants, Philadelphia Giants, Brooklyn Royal Giants, plus a handful of Cuban Winter League teams. Naturally gravitating towards leadership, Johnson usually managed these teams. Then, moving to second to accommodate the next great Black shortstop — John Henry Lloyd, Johnson lifted another two famed squads: the 1910 Chicago Leland Giants and 1913 New York Lincoln Giants.

Grant Johnson, baseball historian Gary Ashwill argues, “was the best everyday player in Black baseball from 1895 to 1909.”1 After slugging his way to a legend with a hometown Findlay, Ohio, club in 1894, “Home Run” Johnson’s career mapped the finest Black teams of the era. He starred at shortstop for the Page Fence Giants, Chicago Columbia Giants, Cuban X Giants, Philadelphia Giants, Brooklyn Royal Giants, plus a handful of Cuban Winter League teams. Naturally gravitating towards leadership, Johnson usually managed these teams. Then, moving to second to accommodate the next great Black shortstop — John Henry Lloyd, Johnson lifted another two famed squads: the 1910 Chicago Leland Giants and 1913 New York Lincoln Giants.

His parents, Charles and Amanda Elizabeth Johnson, were Kentuckians. During the Civil War, Charles served in the Union Army’s 13th Colored Infantry Regiment.2 After the war, the Johnsons settled in Findlay, where Charles worked as a laborer.3 Grant Ulysses Johnson arrived on September 23, 1872.4 Another Ohioan of humble origins, General Ulysses S. Grant, served as Commander in Chief when Charles and Elizabeth named their second son.5

In the mid-1880s, a natural gas and oil boom engulfed northwestern Ohio and Charles worked as an operator.6 Grant played the organ at the A.M.E. church and eventually brought a fine basso voice to its choir.7 He delivered newspapers and ran “a fish and poultry stand.”8 Although his educational status is unclear, as a young man he debated in his church’s literary society.9

Johnson grew into a 5-foot-10, 170-pound frame. He won 100-yard races and took various gymnastic honors; later he demonstrated “skill and speed” in the boxing ring.10 In July 1888 he joined Findlay’s Leons as a first baseman.11 He remained with (likely integrated) local teams for the next several years with the exception of a brief stint with the (likely Black) Cleveland Keystones in 1892.12 Johnson, now a shortstop, spent the 1893 campaign with Findlay. Against the visiting Cincinnati Reds on October 7, the right-handed Johnson drove two Tony Mullane offerings over the left-field fence as Findlay won, 5-4.13 That December, he signed with New York’s Cuban Giants for “a comfortable salary.”14

The Giants were not the dominating force they had been in the late 1880s, but remained one of the finest Black independent teams. Per baseball historians Larry Lester and Dick Clark’s research, in 20 games to begin the 1894 season, Johnson earned a .356 batting average and a .567 slugging percentage.15 Yet when his pay was not forthcoming in late May, Johnson abandoned his promising professional start and returned home.16

Findlay took considerable pride in their native son, yet segregation was overtaking baseball. The city’s newly-minted Sluggers had already signed the accomplished African American second baseman Bud Fowler for the 1894 campaign. Johnson’s return, a local paper reported, was problematic: “The management would like to have [Johnson] but the players are kicking over having two colored players on the club. They say when they go away from home they are unmercifully roasted about such matters, and they don’t like it.”17 Management added Johnson anyhow.

Findlay reportedly won 96 of 112 games in 1894.18 Johnson reportedly hit 60 home runs.19 A Michigan paper proclaimed him “the greatest hitter in the west.”20 Fans nicknamed him “Home Run” Johnson.

A restless baseball entrepreneur, Fowler courted local civic leaders when the Sluggers journeyed to Adrian, Michigan, late in the season. On September 21, the formation of the Page Fence Giants for the upcoming season was announced. The Black team’s financial backing came from the city’s White businessmen, notably fence magnate J. Wallace Page. It was not a profit-making enterprise but instead a marketing vehicle for Page’s fences and (to a lesser extent) the Monarch Bike Company. Fowler (as manager) and Johnson (as captain) would handle the baseball end of the enterprise.

The team travelled in a luxurious train car (with porter and cook), that promoted Page Fence and provided comfortable living quarters independent of Jim Crow restrictions. Dressed in bright red outfits, the players rode their bicycles to the local grounds, with townspeople in tow.21

The Giants lost decisively to the Cincinnati Reds in a pair of April contests, with Johnson going 1-for-8 at the plate and making two errors.22 But the team and its shortstop soon found their bearings. The Giants finished their debut campaign with a reported 118-36-2 record.23 As a sample of his season, over the 13 matches the Giants played against Michigan State League competition, baseball historian Ray Nemec determined that Johnson achieved a team-leading .636 average.24

Fowler departed in midseason, leaving the 22-year-old Johnson in charge of field operations. In the decades ahead, Johnson consistently sought out leadership roles, notably leaving several powerhouse teams where he was a position player for greater authority with lesser organizations.25 At times, he also demonstrated considerable resourcefulness in seeking a more autonomous path. In these regards, Fowler likely influenced him.

In 1896 the Page Fence Giants laid claim to the Black championship: taking five straight games from the Chicago Unions and winning 11 of 19 in a lengthy barnstorming series with the Cuban X Giants (formed that season by several former Cuban Giants).26 In 1897 and 1898 the team exclusively played on the road, with only one game (losing to the Unions, 7-6, on May 9, 1897) against another leading Black team. Yet they remained arguably the Midwest’s strongest independent team, claiming a 129-10 record in 1897 and a 107-10 mark in 1898.27 Johnson often batted third in the order. A Findlay newspaper stated he hit 30 home runs in 1898.28

As the 1898 season concluded, the Page Fence Company, facing economic challenges, decided to no longer sponsor the team.29 Johnson considered working again with Fowler in Findlay; the two purchased grounds in that city in October.30 Yet two months later he signed with Chicago’s Columbia Giants, an upstart outfit financed by the city’s African American Columbia Club.31 Most of the Page Fence team — including pitcher George Wilson, catcher Pete Burns, second baseman Charlie Grant, and outfielder John Patterson — followed Johnson. In 1899 the Columbias swept the Chicago Unions in a five-game series to claim the city’s Black championship, but lost seven of 11 games in a prolonged battle with the X Giants.32

Fowler proceeded to field an integrated team in Findlay. On May 10, 1899, Lima’s (Black) Webster Giants visited. Possibly to lend support to Fowler, Johnson played short for the Giants. A Findlay sportswriter summarized his defensive play: “He has speed to let, and he displayed it in panoramic style. There is a cleverness about his movements that charms. His pickups are clean and pretty. He throws to first with accuracy. He can always be found in the thickest of the fray and at all times he is cool and collected.” Successfully handling 11 of 12 chances, Johnson cleanly picked four “red hot grounders” and made “the star catch of the contest” by snaring a liner “two feet and more” above his head. Comparing Johnson to the finest defensive major-league shortstop of the mid-1890s, the scribe concluded, “He’s the Hughie Jennings of colored players.”33

By 1900, Chicago’s Black teams were under duress, in part due to the demise of several leading White semipro teams with whom the Columbias and Unions had maintained rivalries.34 That January, Unions owner William Peters struck back at the Columbias by signing Johnson.35 The growing hostility between the two teams prevented them from meeting in 1900, although the Unions took a pair of games from the Cuban Giants that summer.36

Johnson returned to the Columbias in January 1901 and worked to ensure their sustainability. He opened a “cigar and tobacco store in Chicago” and soon the Columbia Giants were rebranded the Royal Tiger Giants, after a cigar brand.37 Some financial backing likely came from Seward French, a Black Chicagoan later identified as the team’s new magnate.38 In smaller Midwestern cities where the Page Fence Giants were well known, the squad was promoted as the Royal Tigers, often with references to the Page Fences. (Although, reflecting an independent team’s tight budget, they played in Columbia Giants uniforms.)39 In Chicago, brand recognition dictated they play as the Columbias. In this capacity, after taking a second straight game from the Unions on October 13, Johnson’s squad again claimed a championship.40

The Cuban X Giants, arguably the East’s leading Black team, reportedly signed Johnson prior to the 1902 season for “$100 per month and his expenses.”41 Yet, come April, he returned to captain and manage the Columbias. The Royal Tiger marketing tie-in ceased, and the team played Sundays in the White Sox’s South Side Park when the American League team was away. The Union Giants, Chicago’s newest contending Black team and stocked with several of Johnson’s former colleagues, took a three-game series from the Columbias that summer.42

Webber Harrison, briefly with the Columbias in 1902, provided an insight into his manager’s disciplined “inside” strategies. “The squeeze was one of Johnson’s favorite plays. The runner on third was to give the batter the signal when he intended to start for the plate. If on the first ball pitched, he made a motion with his right foot; if on the second ball, a motion with his left foot. We were continually drilled to learn this play.”43

X Giants’ owner Edward Lamar landed Johnson for the 1903 season, reportedly for the same terms offered the year before.44 Returning east for the first time since 1894, Johnson impressed onlookers as “a fast man” and “a great shortstop [who] throws to first like a machine.”45 On June 17, 1903, when the X Giants visited York, Pennsylvania, he helped preserve Dan McClellan’s perfect game (the first in Black baseball history). “Twice he went into the outfield for high flys,” a York observer wrote, “and in the ninth inning he made a one-handed stop and quick throw of Lipp’s hard grounder, which under ordinary circumstances would have been a base hit.”46 In September, behind the pitching of Rube Foster, the X Giants (aka Cubes) won five of seven games from the ascendant Philadelphia Giants (aka Phillies). Johnson contributed eight hits and handled 27 of 30 chances cleanly in the series.47

Johnson played winter ball in Cuba after the 1903 season. Next he landed in Palm Beach to play with the Royal Poinciana team in the Florida Hotel League.48 He spent an April stint in Lima managing their Giants team.49 By May he was back with the Cubes, a somewhat weakened squad as several players (including Foster and Charlie Grant) had signed with the Phillies. This shift in fortunes was confirmed in September when the Phillies took a three-game series between the teams. When Johnson came back to Findlay later that month, he briefly played short for the local team.50 Then, as he returned to Cuba and Florida that winter, the cycle began again.51 Yet before heading south, he signed a contract with the Phillies for the coming season.52

The 1905 Phillies fielded one of the strongest lineups Johnson was ever part of. Grant led off and played second. Outfielder Pete Hill, possibly the team’s finest hitter, typically batted second in the order. Bill Monroe, moving from short to third to accommodate Johnson, batted third. Shortstop Johnson batted cleanup (or third, when Monroe was lost to injury). Manager Sol White or Harry Moore played first base and typically batted fifth. Foster, McClellan, and Emmett Bowman each won thirty games (Johnson won several games as the rare fourth starter) and manned outfield positions when not pitching. Catchers Pete Booker and Tom Washington typically batted ninth.

The Phillies rolled to a 128-23-3 record.53 Per baseball historian Phil S. Dixon, Johnson hit at least eight home runs in the first 36 games (nine of these lack any box scores).54 On May 18, Johnson injured a tendon in his leg and was hospitalized.55 He battled back within two weeks, but his slugging fell off. Still, from the games with surviving box scores, Johnson led the team with 12 homers.

Despite his power, Johnson was a disciplined hitter, later telling a sportswriter, “when I [struck out] I surprised myself.”56 In 1907 Johnson contributed an “Art and Science of Hitting” essay to Sol White’s Official Base Ball Guide. He began by identifying “confidence and fearlessness” as the truest attributes of “a first-class hitter.” “Most young players,” Johnson thought, “make the natural mistake of trying to become home-run hitters and hit the ball with all the force at their command at all times with a full swing of the bat.” To “get a line on the speed or curve of the pitcher” a first pitch should generally be studied, not swung at. Then “with only ordinary force behind the swing,” the batter should strive to “meet the ball and place it to the best advantage.” Finally, Johnson advised, “To improve the eye, I find bunting to be very effective, and should be practiced before each game as a player who can both hit and bunt is a very valuable man to any team.”57

Following the 1905 season, Johnson signed a contract to play for and manage the Brooklyn Royal Giants.58 The Royals, owned by Black restaurateur John W. Connor, needed work. In 1905 the team compiled an 0-11-1 record against the Phillies. Johnson recruited a few pieces, including ex-Page Fence teammate Billy Holland from the Chicago Unions, then left for another winter of Florida ball.59 In March, a report had him joining the upstart Philadelphia Quaker Giants.60 Yet, come Opening Day, he was with the Royals.61

After the Quakers collapsed in September, the Royals picked up several players, most notably Bill Monroe. Although the gap had been narrowed, Brooklyn again finished short of the Phillies. Per Seamheads.com’s Negro Leagues Database, Johnson compiled a slash line of .362/.459/.606 in 24 documented games against other Black independents. His OPS of 1.066 topped regulars from eastern Black teams.

On October 29, 1906, Johnson attended the formation of the National Association of Colored Base Ball Clubs in Brooklyn.62 Five teams were represented: the Philadelphia Giants, Cuban X Giants, Brooklyn Royal Giants, Cuban Giants, and Cuban Stars. Phillies owner Walter Schlichter was elected president and John Connor vice-president. The new league’s secretary, Nat Strong, wielded the most power, for he controlled the most lucrative bookings in the New York City area. The NACBC sought to avoid salary wars by capping player pay at $100 monthly.63 Johnson may well have received an additional stipend from Connor for his managerial role.

For the next two seasons, Johnson alternated between Cuban Winter League play and leading the Royals. After the 1906 season, he joined Grant, Monroe, Hill, and Foster in playing for Fé. Then he led the Royals to a third-place finish in the 1907 NACBC race.

Johnson returned to Cuba in October 1907, as part of a Phillies team playing a lengthy “American Series” versus Almendares and Habana teams. For the first time, he formed a double-play combo with John Henry Lloyd. After a respite, he returned in January to captain the Habana team in their league season. That summer the Royals overcame the Phillies to take the NACBC crown. Johnson returned to Cuba over the 1908-1909 offseason, playing in another American Series and again captaining Habana.

On April 28, 1909, Johnson married Moena Scott, a North Carolina native, in Florida.64 He also helped raise Moena’s daughter Grace.65 Seemingly from a previous union, a son of Johnson’s was mentioned playing for the Lima Giants in 1916.66 Much later in life, New York State marriage records suggest he may have married again in 1954.67

Since his Page Fence days, a small, spotted terrier named Money had accompanied Johnson as he barnstormed. When he first took the puppy in, Johnson carried her in his overcoat. As she grew, to conceal her from train conductors, he carried Money in a basket.68

In 1909 the Royals again proved the east’s strongest Black team and capped their season on October 8 by beating the American League’s New York Highlanders, 9-6.69 Johnson then returned to the Habana team. As they won four of six games against the AL pennant-winning Detroit Tigers, he hit .412.70

In February 1910, Connor sought to trade Johnson to the Phillies for John Henry Lloyd.71 When the report surfaced, Johnson and Lloyd were playing hotel ball in Florida with Rube Foster’s Chicago Leland Giants.72 Both jumped to the Lelands. Connor later maintained that Johnson “got angry because I refused to give him an interest in the Royal Giants.”73

The 1910 Lelands, like the 1905 Phillies, were one of the finest Black teams of the era. Catcher Bruce Petway handled pitchers Frank Wickware, Foster, and Pat Dougherty. Centerfielder Pete Hill was flanked in left by Frank Duncan and in right by Andrew “Jap” Payne. Johnson, for the first prolonged stretch in his career, moved to second to accommodate Lloyd. Johnson typically batted third, behind Hill and in front of Lloyd.

The team amassed a 123-6 record. Seamheads documents a .326/.368/.461 slash line for Johnson in 21 games. His .829 OPS was third on the team, behind Hill and Lloyd. Now 37, teammates called him “Dad.”74 He was “quite a favorite” with fans, a sportswriter observed, “His witty sayings, good playing and gentlemanly conduct won him many friends.”75 Another newspaperman later called Johnson “one of the fairest and cleanest players in baseball.”76 The conclusion seems apt: through his decades-long career, there is no evidence that his professionalism and sportsmanship ever wavered.

Johnson hit only .170 in 13 games with the Lelands as they visited Cuba after the 1910 campaign. Next, he joined Habana in Winter League action. Then he again chose to leave a dominant team for one seeking to make a mark. Ironically, in 1911, this was the Philadelphia Giants, a subpar club since Sol White had departed after the 1908 season.

As the Phillies’ new manager, Johnson had two young stars to work with: catcher Louis Santop and pitcher Dick Redding. Yet the team struggled and, when Santop and Redding left for the New York Lincoln Giants in July, it collapsed.77 Johnson landed with the Chicago Giants, batting only .219 in nine games documented by Seamheads.

After the 1911 season, he led Habana to the Cuban Winter League pennant. In 30 games, he compiled a slash line of .410/.483/.486. His .969 OPS led all regulars, which included Lloyd, Hill, Petway, Detroit’s Matty McIntyre, and Cincinnati’s Armando Marsáns. “Like wine,” a Cuban newspaper observed, “[Johnson] appears to improve with age.”78 It was, however, his final visit to the island.

Johnson returned to manage another former team, the Royals, in 1912. Yet the organization suffered both from defecters (outfielder Spottswood Poles) and falling attendance.79 On October 28, Johnson was in the Lincoln Giants lineup as Joe Williams shut out a barnstorming team largely comprising the pennant-winning New York Giants, 6-0.80 Johnson was not among the contingent of Lincolns who played in Cuba that winter, but he did star for the Florida Hotel League.81

In 1913 Johnson arrived in Schenectady, New York, to captain the new Mohawk Colored Giants.82 Yet Jess McMahon, the Lincolns’ co-owner, successfully recruited Johnson in May.83 Again, Johnson helped elevate a team to legend. Centerfielder Poles usually led off the Lincolns’ attack, followed by leftfielder Judy Gans. Lloyd, managing and playing short, batted third. Johnson, at second, batted cleanup. Santop and Doc Wiley typically alternated between catching and right field while batting fifth. First baseman Leroy Grant, third baseman Bill Francis, and pitching ace Williams appeared in the bottom third of the order. The Lincolns bested Rube Foster’s dominant Chicago American Giants in a lengthy series that summer and, for good measure, trounced Pete Alexander and the Phillies, 9-2, on October 5.84 Seamheads.com, from 17 games, documents a .439/.493/.485 slash line for the 40-year-old Johnson with the Lincolns in 1913.

Before the 1914 season, James J. Keenan became the Lincoln Giants’ president and Johnson replaced Lloyd (who had joined the American Giants) as manager.85 Johnson played through mid-May then fell off the roster, with Dick Wallace taking over as shortstop and manager. Johnson’s whereabouts for that summer are elusive.86

In April 1915, Johnson signed with the Pittsburgh Colored Stars.87 Despite its name, the team was centered in Buffalo, not western Pennsylvania. At short, Johnson still chased down flies on the “left field foul line” and helped turn “lightning double plays.”88 The Stars’ lineup featured ex-teammates of Johnson’s (Phil Bradley, Mike Brown) and, by 1917, future Negro League mainstays (Toussaint Allen, Phil Cockrell).

For a decade, with Johnson at the helm, the Stars were one of the strongest semipro teams in western New York. When not playing on the weekends, Johnson worked as a railroad porter.89 By 1926, Pete Hill arrived in Buffalo, and Johnson joined his ex-teammate’s team.90 As late as 1931, mentions of Johnson still playing semipro ball appeared.91

Remaining in Buffalo, Johnson continued to work as a porter and remained active in his church and its choir.92 In 1951, he selected Jackie Robinson as the best all-around ballplayer of that time, and praised the “exceptionally good” Larry Doby and Luke Easter.93 Johnson later lost his sight and lived in the Erie Home of the Blind. On September 4, 1963, he died of heart failure after a surgery. Grant Johnson was buried in Lakeside Cemetery in Hamburg, New York. In 2014, through the efforts of SABR’s Negro Leagues Grave Marker Project, a plaque honoring his career was unveiled near his resting place.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin. The author also thanks fellow SABR member Howard Henry for providing information regarding Johnson’s marriage to Moena Scott.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Johnson’s file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame and the following sites:

findlaylibrary.advantage-preservation.com/

Unless otherwise stated, Grant Johnson’s baseball statistics were compiled by SABR members Gary Ashwill and Kevin Johnson and are available at Seamheads.com.

Notes

1 Gary Ashwill, Notes towards Sol White’s Official Base Ball Guide by Sol White (South Orange, NJ, Summer Game Books, 2014): 151.

2 Charles Johnson’s obituary [Findlay (Ohio) Union, October 3, 1901: 8] states he was a soldier. The 1890 Veterans Schedule lists a Charles Johnson, of Findlay, Ohio, serving in the 13th Colored Infantry.

3 Per the 1870 and 1880 U.S. Censuses.

4 Johnson’s birth year has sometimes been given as 1873 or 1874, yet the Ohio Births and Christenings Index indicates 1872, while the 1900 census also indicates 1872. His middle name (beyond an initial) seems to have been indicated only once, in his 1937 Social Security application, as Ulyssess with an extra ‘s.’ The more common spelling of Ulysses is assumed here.

5 Grant was the fourth of five children to reach adulthood: Charles (1867), Anna Belle (1868), and Ida (1869) preceded him, while Andrew (1873) followed.

6 Within the 1892-93 city directory (contained within Johnson’s Hall of Fame file), Charles is identified as an “opr wks The SWN Co.”

7 “Pencil Chips,” Hancock Courier (Findlay, Ohio), January 1, 1885: 3; “United,” Findlay (Ohio) Courier, October 16, 1899: 2.

8 “Lecture Postponed,” Cleveland Gazette, December 10, 1887: 2; “Buckeye Letters,” Cleveland Gazette, November 30, 1889: 2.

9 “Findlay O., Cullings,” Cleveland Gazette, March 4, 1893: 1.

10 “Findlay Always Wins,” Morning Republican (Findlay, Ohio), September 24, 1891: 7; “Took the Honors at a Gymnasium Contest,” Cleveland Gazette, January 28, 1893: 3; “Riley vs Johnson,” Findlay (Ohio) Courier, January 7, 1901: 8.

11 “Now the Leons,” Morning Republican (Findlay, Ohio), July 7, 1888: 1.

12 For mentions of Johnson with Findlay teams, see “Gas Citys vs. Bellaires,” Findlay (Ohio) Jeffersonian, August 30, 1888: 1; “Baseball,” Findlay (Ohio) Jeffersonian, July 11, 1889: 7; “The Leon’s at Sandusky,” Morning Republican (Findlay, Ohio), July 19, 1892: 5. For mention of him with the Keystones, see Morning Republican (Findlay, Ohio), August 3, 1892: 8. For background on the Keystones later in the decade, see James E. Brunson III, Black Baseball 1858-1900, Volume 1 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2019), 199.

13 “The Season Closed,” Findlay (Ohio) Courier, October 9, 1893: 4.

14 “Base Ball Matters,” Findlay (Ohio) Courier, December 26, 1893: 4.

15 Dr. Layton Revel and Luis Munoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Grant ‘Home Run’ Johnson,” Center for Negro League Baseball Research, www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/EP/330059%20Grant%20Johnson_1up.pdf, accessed August 31, 2020.

16 “Findlay Won,” Findlay (Ohio) Courier, May 25, 1894: 4.

17 Findlay (Ohio) Courier, May 24, 1894: 4.

18 “The Efforts of Dr. Drake Are Glorious,” Findlay (Ohio) Courier, April 19, 1899: 2. Note it was not uncommon for boosters of a team in this era to inflate their seasonal records.

19 Johnson himself hinted that his career high was 40. See “Most Famous Colored Baseball Player in Country to Captain ‘Bill’ Wernecke’s New Local Nine,” Schenectady Gazette, March 4, 1913: 11. Yet a contemporary newspaper references him hitting his 58th: “Home Run Johnson,” Adrian (Michigan) Telegram, September 20, 1894: 3.

20 “Bluffs Didn’t Go,” Adrian (Michigan) Telegram, August 31, 1894: 3.

21 For full details, see Mitch Lutzke, The Page Fence Giants: A History of Black Baseball’s Pioneering Champions (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2018): 24-40.

22 “‘Come Seven and Then Come ‘Leven,’” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 12, 1895: 2; “Slaughtered,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 13, 1895: 2.

23 “Giants Great Record,” Adrian (Michigan) Telegram, October 18, 1895: 2.

24 The next highest average from a Giant in these games was .467. Lutzke, The Page Fence Giants: 238. Note Nemec’s work is located within Bud Fowler’s Hall of Fame file.

25 Manager identification per Seamheads.com

26 Lutzke, The Page Fence Giants: 163-175, 241.

27 For 1896, 1897, and 1898 records, see “Have Good Record,” South Bend (Indiana) Tribune, May 1, 1899: 3.

28 “Base Ball,” Findlay (Ohio) Jeffersonian, October 13, 1898: 5.

29 Lutzke, The Page Fence Giants: 224-231.

30 “Ball Grounds,” Morning Republican (Findlay, Ohio), October 27, 1898: 1.

31 “Ball Grounds,” Findlay (Ohio) Union, December 22, 1898: 8. For background on the Columbia Giants, see Michael E. Lomax, Black Baseball Entrepreneurs, 1860-1901: Operating by Any Means Necessary (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2003): 159-161.

32 Lomax, Black Baseball Entrepreneurs, 1860-1901: 166.

33 “The Giants Couldn’t Stand the Clever Pace,” Findlay (Ohio) Courier, May 11, 1899: 3.

34 Lomax, Black Baseball Entrepreneurs, 1860-1901: 168-170.

35 “Unions Sign Grant Johnson,” Chicago Tribune, January 21, 1900: 19.

36 “Unions, 10; Cuban Giants 5,” Chicago Tribune, June 25, 1900: 8; “Unions, 6; Cuban Giants 3,” Chicago Tribune, July 2, 1900: 8.

37 Findlay (Ohio) Jeffersonian, January 10, 1901: 2; “New Name for Page Fence Giants,” Detroit Free Press, March 17, 1901: 31.

38 “Chicago,” The (St. Paul) Appeal, April 20, 1901: 5. Also see French’s obituary: Chicago Tribune, April 3, 1936: 22.

39 “Dragged in the Dust of Defeat Were Locals,” The (Canton, Ohio) Repository, July 8, 1901: 2.

40 “Columbia Giants, 3; Union Giants 2,” Chicago Tribune, October 14, 1901: 4.

41 “Grant Johnson,” Weekly Jeffersonian (Findlay, Ohio), February 6, 1902: 1.

42 “Union Giants, 7; Columbia Giants, 3,” Chicago Tribune, July 28, 1902: 8; “Union Giants Are Champions,” Chicago Tribune, August 4, 1902: 6.

43 Jack Ryder, “Calmly Confident is Herrmann,” Cincinnati Enquirer, January 15, 1908: 4.

44 “Is a Giant Again,” Weekly Jeffersonian (Findlay, Ohio), February 5, 1903: 2.

45 “Cuban X-Giants Took Game,” Evening Journal (Wilmington, Delaware), April 28, 1903: 6; “Baseball Games by the Clubs of Chester,” Chester (Pennsylvania) Times, May 14, 1903: 4.

46 “M’Clellan’s Great Pitching,” Gazette (York, Pennsylvania), July 18, 1903: 1.

47 “Cuban X-Giants Win First Game,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 13, 1903: 14; Brooklyn Standard Union, September 15, 1903: 9; “Cuban X-Giants Won Miserable Game,” Trenton (New Jersey) Times, September 15, 1903: 8; “M’Clellan Lost Pitcher’s Battle,” Camden (New Jersey) Post-Telegram, September 16, 1903: 3; “Fun for Spectators in Battle of Colored Giants,” Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Star-Independent, September 19. 1903: 4; “X Giants Beat the Phillies,” Camden (New Jersey) Courier, September 26, 1903: 6.

48 For more on Johnson’s Cuba and Florida playing, see Revel and Munoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Grant ‘Home Run’ Johnson.”

49 “To Coach Lima Team,” Republican-Jeffersonian (Findlay, Ohio), March 29, 1904: 6.

50 “Big League Exhibition,” Morning Republican (Findlay, Ohio), September 28, 1904: 3; “Three Out of Four to Blues,” Findlay (Ohio) Courier, September 29, 1904: 7. Note Johnson was apparently the only Black player in this series between Findlay and Lima.

51 “A Sparkling Letter from Grant Johnson,” Morning Republican (Findlay, Ohio), October 22, 1904: 7; “Will Make Trip South,” Morning Republican (Findlay, Ohio), December 28, 1904: 7.

52 “Grant Johnson Signs,” Courier-Union (Findlay, Ohio), December 16, 1904: 8.

53 Phil S. Dixon, Phil Dixon’s American Baseball Chronicles – Great Teams: The 1905 Philadelphia Giants Volume III (Xlibris, 2010): 22-23.

54 Dixon, The 1905 Philadelphia Giants: 42-43, 277-279.

55 Dixon, The 1905 Philadelphia Giants: 83.

56 Link Groves, “Grant Johnson’s Findlay Visit Recalls Great Baseball Career,” Republican-Courier (Findlay, Ohio), July 21, 1951: 11. [From Johnson’s Hall of Fame file.

57 Sol White, Sol White’s Official Base Ball Guide (South Orange, NJ, Summer Game Books, 2014): 119-121.

58 “Grant Johnson Returns Home,” Morning Republican (Findlay, Ohio), November 4, 1905: 2.

59 On recruitment, see “Royal Giants Announce Line Up for 1906,” Brooklyn Standard Union, December 15, 1905: 8. On Florida, see “At Palm Beach,” Courier-Union (Findlay, Ohio), December 5, 1905: 5; “Base Ball,” Philadelphia Item, February 27, 1906: 8.

60 “Baseball Chat,” Weekly (Brooklyn) Chat, March 31, 1906: 12.

61 “Baseball,” Brooklyn Citizen, April 2, 1906: 5.

62 “New Base Ball League Bobs Up on Horizon,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 29, 1906: 10.

63 Walter Schlichter, “Slick’s Salad,” Philadelphia Item, January 29, 1907: 7.

64 For the marriage license, see digital.lib.usf.edu/SFS0057301/00001 from Hillsborough County (Florida)’s digital collections. For a Findlay mention, see “Johnson Married,” Findlay (Ohio) Courier, May 7, 1909: 2.

65 The 1910 census shows Moena living in Amanda Elizabeth Johnson’s Findlay household, with her three-year-old daughter Grace. Moreover, Grace’s father’s birthplace is listed as North Carolina. For a later Findlay mention of Grace, see “Society,” Findlay (Ohio) Courier, July 29, 1915: 3.

66 “With the Fort Wayne Ball Club,” Fort Wayne (Indiana) News, August 24, 1916: 9. The son’s name was not given.

67 Within the 1954 records, a Grant Johnson of Buffalo is listed as a groom.

68 “Johnson’s Mascot is Always with Master,” Republican-Jeffersonian (Findlay, Ohio), May 20, 1909: 6.

69 Lester A. Walton, “In the Sporting World,” New York Age, October 14, 1909: 6; Lester A. Walton, “The Base Ball Spirit in the East,” The Freeman (Indianapolis, Indiana), December 25, 1909: 7.

70 Revel and Munoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Grant ‘Home Run’ Johnson.”

71 Lester A. Walton, “In the World of Sport,” New York Age, February 24, 1910: 6.

72 “Hotly Contested Games in Southland,” The Freeman (Indianapolis, Indiana), February 26, 1910: 7.

73 Lester A. Walton, “In the World of Sport,” New York Age, April 14, 1910: 6.

74 James H. Smith, “The Past and Present in Baseball,” The Freeman (Indianapolis, Indiana), May 28, 1910: 7.

75 “The Leland Giants,” The Freeman (Indianapolis, Indiana), July 2, 1910: 5.

76 Edward Tranter, “Sport Topics,” Buffalo Enquirer, October 29, 1917: 8.

77 Lester A. Walton, “In the World of Sport,” New York Age, August 3, 1911: 6.

78 A Havana Daily Post article presented in “Johnson Was Especially Good,” Findlay (Ohio) Courier, May 6, 1912: 7.

79 “In the World of Sport,” New York Age, June 13, 1912: 6; Lester A. Walton, “In the World of Sport,” New York Age, August 1, 1912: 6.

80 “Lincolns Defeat Giants,” New York Age, October 31, 1912: 6.

81 “Baseball Notes,” New York Age, January 16, 1913: 6.

82 See “Most Famous Colored Baseball Player in Country to Captain ‘Bill’ Wernecke’s New Local Nine,” Schenectady Gazette, March 4, 1913: 11; “Home Run Johnson and Phil Bradley Arrive Last Night,” Schenectady Gazette, March 22, 1913: 13.

83 “Mohawk Giants Break Even in Double Header with Oswego Club; Seriously Handicapped Yesterday,” Schenectady Gazette, May 5, 1913: 9; “Lincoln Giants to Play Royal Giants in Hoboken,” Brooklyn Times, May 16, 1913: 10.

84 For the American Giants series, see Larry Lester, Rube Foster in his Time: On the Field and in the Papers with Black Baseball’s Greatest Visionary (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2004): 71-73. For the Phillies’ game, see “Philadelphia Nationals Lose; Walter Johnson Defeated,” New York Age, October 9, 1913: 6.

85 “Semi-Pro Teams Plan Big Season,” Brooklyn Eagle, March 24, 1914: 20.

86 In June, a Johnson plays left field for the Pittsburg Colored Stars of Buffalo (the squad Johnson would clearly be part of in 1915). See “Colored Stars Lose,” Pittsburgh Press, June 7, 1914: 24. In September he is specifically mentioned as being on the Newark Colored Giants team, but the Johnson that plays for them is at first base. See “Cogan’s Team Will Cross Bats with Newark Colored Giants,” Paterson (New Jersey) Evening News, September 12, 1914: 6; “Paterson Team Was a Winner,” Paterson (New Jersey) Morning Call, September 14, 1914: 3. With the exception of isolated pitching appearances, there isn’t any indication of Grant Johnson playing any position other than shortstop or second base from 1893 onwards.

87 “Semi-Pro Notes,” Brooklyn Eagle, April 19, 1915: 19.

88 “Pittsburgh Stars Win Game in Early Innings,” Buffalo Evening News, June 19, 1916: 1; “Fitzpatrick Twirls Pures to Victory Over Stars,” Buffalo Courier, July 26, 1915: 8.

89 In early 1919, he was identified working with the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad. See “Colored Baseball Star Will Be in Game In 1919,” Weekly Jeffersonian (Findlay, Ohio), January 2, 1919: 1.

90 “Petey Hill’s Team Ready for Action,” Buffalo Times, July 2, 1926: 15.

91 “Sport of All Sports,” Bradford (Pennsylvania) Evening Star and Daily Record, April 16, 1931: 8.

92 For details of his final years, see “Grant Johnson Taken by Death,” Republican-Courier (Findlay, Ohio), September 5, 1963. [From Johnson’s Hall of Fame file.

93 Link Groves, “Grant Johnson’s Findlay Visit.”

Full Name

Grant Ulysses Johnson

Born

September 23, 1872 at Findlay, OH (US)

Died

September 5, 1953 at Buffalo, NY (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.