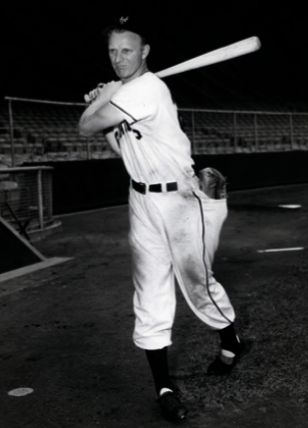

Whitey Lockman

Most baseball fans are aware of “The Shot Heard ’Round the World,” Bobby Thomson’s dramatic ninth-inning home run off Ralph Branca that won the 1951 pennant for the New York Giants. Fewer may be cognizant of Whitey Lockman’s role in setting the stage for that climatic event. Had Lockman not made a crucial hit before Thomson came to the plate, the Staten Island Scot would not have faced Branca, nor would a homer have been sufficient to win the game for the Giants.

Most baseball fans are aware of “The Shot Heard ’Round the World,” Bobby Thomson’s dramatic ninth-inning home run off Ralph Branca that won the 1951 pennant for the New York Giants. Fewer may be cognizant of Whitey Lockman’s role in setting the stage for that climatic event. Had Lockman not made a crucial hit before Thomson came to the plate, the Staten Island Scot would not have faced Branca, nor would a homer have been sufficient to win the game for the Giants.

Carroll Walter Lockman was born on July 25, 1926, in Lowell, North Carolina, youngest of the six children of Eunice Ellen Jenkins and Charles Ramsey Lockman.1 Lowell, in Gaston County, is a suburb of Gastonia in the Charlotte metropolitan area in the southwestern part of the state, not far from the South Carolina line. Charles Lockman was a longtime textile-mill employee, working in various capacities from machine operator to assistant superintendent in mills in both Carolinas. He died on March 17, 1927, when his youngest son was 7 months old. After her husband’s death, Eunice Lockman worked long hours in textile mills to support the family. The 1930 census showed 3-year-old Walter living with his widowed mother and four siblings in Charlotte. The 1940 census placed the family in the Paw Creek neighborhood of Charlotte. Two of the Lockman children were employed in 1940, helping the fatherless family with living expenses. Mary was working as a trimmer in a textile mill. Charles Jr. was a professional boomball player.2

When he was a child, the future big leaguer was known as “Pickle” in honor of a well-liked policeman in the neighborhood. He was never called Whitey until he joined the Giants, where his light blond locks earned him the new moniker.3 The lad started playing baseball when he was 8 years old. As a teenager he excelled at Gastonia High School and in American Legion ball. The manager of his Legion club recommended Lockman to Giants scout Bill Pierre. As the Gastonia school had only 11 grades, instead of the usual 12, Lockman graduated at the age of 16 in April 1943. Pierre signed him for the New York Giants in May for a $1,000 signing bonus. Lockman later told an interviewer, “That doesn’t seem like much in comparison to what kids are getting now, but it was a lot of money to me then, and I was very happy about it.”4

Lockman made his professional debut with the Springfield (Massachusetts) Rifles of the Eastern League at the age of 16. He hit .325 for Springfield in 40 games, earning a quick promotion to the Giants’ highest minor-league affiliate, the Jersey City Giants of the International League, where he played in 78 games, scored 35 runs and drove in 18. He returned to Jersey City in 1944, playing in 141 games, scoring 81 runs and knocking in 56. He showed some speed on the basepaths, stealing 15 bases in 21 attempts. After the 1944 season, with World War II still raging, Lockman joined the Merchant Marine.5 He returned to baseball at the start of the 1945 season, back in Jersey City. In midseason he was called up to the big club.

Lockman, a 6-foot-1, 175-pound outfielder who batted left-handed, and threw right-handed, made his major-league debut for the Giants at the Polo Grounds on July 5, 1945, at the age of 18. And what a debut it was! Batting third in the lineup against the St. Louis Cardinals, Lockman came up to bat in the first inning against George Dockins with one man on and one man out. He promptly hit a two-run homer in his first major-league plate appearance. In the fourth inning he clouted a two-run double. For his inaugural day Lockman went 2-for-4, with four RBIs. After this auspicious start Lockman spent his entire playing career in the major leagues. He never played another game in the minors. Although he appeared in only 32 big-league games before enlisting in the Army on August 10, he started in center field in every Giants game from his debut to his enlistment. Mel Ott was Lockman’s manager for only a few weeks, but years later Lockman credited Ott with being a positive influence on his life and career.6 The manager took the scared teenager under his wing, bolstered his confidence, taught him to be a better hitter, and helped the youngster adjust to life in the big city.

Unlike some major leaguers who spent their years in the service playing baseball, Lockman played only one game on his first base, Fort Dix, New Jersey. Although Fort Lewis, Washington, the site of his next assignment, had an outstanding team, he did not play baseball there.7 For most of the next two years Lockman served as a technical sergeant aboard a Navy transport ferrying across the Pacific.8

After missing the entire 1946 season, he was discharged from the service in time to join the Giants during spring training in 1947. On April 7, one week before the pennant race was scheduled to start, the Giants were playing the Cleveland Indians in an exhibition game in Sheffield, Alabama. With Lockman on first base, teammate Clint Hartung hit a slow roller to Cleveland shortstop Lou Boudreau. “I had a pretty good jump and never thought Boudreau would try to make a play on me,” Lockman said. “I was coming into second base standing up. But Lou fooled me. Just as he caught the ball he whirled around and flipped to second. I started to slide. It was too late. I was too close to the base. My spikes stuck in the bag, and I could feel my ankle snap.”9 Lockman was carried off the field with a broken ankle. He spent six weeks in a hospital, with his leg in a cast, then recuperated at home. It was late summer before he rejoined the club. Even then, his ankle was too weak for him to play in the outfield. He appeared in only two games in the final week of the season, both times as a pinch-hitter.

After 75 games in the 1948 season, Mel Ott was replaced as manager of the Giants by Leo Durocher. Adjusting to the new manager was not easy for Lockman. A respected mentor to the young man, Ott was kindly, soft-spoken, and easy-going, famously a “nice guy.” In some ways Durocher was his opposite – brash, loud, volatile, and prone to rant and rave at his players. Once he got to know him, Lockman came to appreciate how Durocher operated. “As our relationship developed … I realized the guy was a heck of a manager. There might have been some things you didn’t agree with him about, like his personal habits in life, but what the heck? You were a professional and what he did on the field between the white lines was what counted.”10

When his big-league career resumed, Lockman established himself as a regular, usually starting in left field, sometimes in center, and occasionally at first base, but rarely missing a game. The power he displayed in his major-league debut was an anomaly. He was not regarded as a power hitter. He was a line-drive hitter, an excellent bunter, and a speedy baserunner. In his career he had far more runs scored than runs batted in, 836 to 563. For his first three full seasons with the Giants, he averaged just under .300 with more than 95 runs scored and nearly 60 runs batted in per season. He hit a career-high 18 homers in 1948.

With the addition of outfielders Monte Irvin and Willie Mays to the lineup, Lockman became the Giants’ first baseman. In the legendary playoff game of October 3, 1951, he was playing first base and batting fifth in the lineup. As most baseball fans know, the Giants had come from far behind to tie the Dodgers on the last day of the season. The two clubs had split the first two games of the best two-out-of-three playoff series. Going into last half of the ninth inning of the pennant-deciding game, the Dodgers held a 4-1 lead. Alvin Dark led off for the Giants with a single off Dodgers ace Don Newcombe. Don Mueller followed with a single to put runners on first and third. Monte Irvin hit a foul fly for the first out. Lockman came up and hit a line-drive double just inside the left-field foul line, scoring Alvin Dark and sending Mueller to third. Mueller injured an ankle as he arrived at the base. Clint Hartung came in to run for Mueller. Lockman’s hit had made the score 4-2 and put the potential tying runs on base. More importantly, it knocked Newcombe out of the box. In came Ralph Branca to pitch to Thomson, which would not have happened had Lockman not reached base. Not only that but the tying run would not have been on base, nor would Thomson have scored the winning run, if not for Lockman’s safety. Lockman had set the stage, and Thomson delivered perhaps the most famous home run in the history of baseball.

“My one thought when I came up to bat in the ninth was to go all out for a homer, although I wasn’t much of a home-run hitter, especially against Newcombe,” Lockman told writer Ray Robinson. When the first pitch came in, high and on the outside corner, Whitey took it for a strike. The second pitch came in at the same spot. Lockman knew it was impossible to hit it for a homer. “My instinct and muscle control took over. … I sliced it to left.”11 In the celebration following the epic win, Lockman injured his shoulder and neck in helping teammates lift Thomson over their heads. “It sure screwed me up for the World Series,” Lockman told Thomas Kiernan. “I could hardly throw or swing a bat the whole Series.”12 The New York Yankees won the World Series in six games.

After 1951, Lockman played nine more seasons in the major leagues, having one of his best years in 1952, when he hit .290, scored 99 runs, and was named to the National League All-Star team. From 1952 through 1955 he was a solid performer for the Giants, averaging 150 games played per season.

On June 14, 1956, he was traded with Al Dark Ray Katt, and Don Liddle to the St. Louis Cardinals for Jackie Brandt, Dick Littlefield, Bill Sarni,Red Schoendienst, and a player to be named later (Gordon Jones). Lockman stayed only a short time with the Cardinals. On February 26, 1957, he was traded back to the Giants for Hoyt Wilhelm. He was with the Giants when they moved from New York to San Francisco prior to the 1958 season.

On February 14, 1959, he was purchased by the Baltimore Orioles, who traded him to Cincinnati on June 23 for Walt Dropo. He ended his playing career with the Reds on June 24, 1960, at the age of 33. With the Reds trailing the San Francisco Giants 5-2 in the ninth inning, Dutch Dotterer led off the bottom of the frame with a walk. Manager Fred Hutchinson sent Lockman in to run for the slow-footed catcher. Lockman went to third on a single by Roy McMillan, and scored as Jerry Lynch hit into a double play, making the score 5-3. The Reds then lost the game when Ed Bailey lifted a pop fly to the shortstop. It was not a great ending to a long and distinguished major-league career, but Lockman had done all his manager had asked him to do. It is perhaps fitting that Lockman’s final game was against the Giants, the same club for which he had made his major-league debut 16 years earlier, although the Giants were now located in a different city, far from the Polo Grounds and Coogan’s Bluff.

His playing career was over, but Whitey Lockman stayed in baseball for many more years. He retained a relationship with the game for almost his entire life, working long past the normal retirement age. He finally retired in 2001 at the age of 75. As soon as his playing days were over he joined the Reds’ coaching staff. From 1961 through 1964 he was the third-base coach for the Giants. Then he joined the Chicago Cubs organization, working variously as a minor-league manager, major-league coach, and director of player development. In midseason 1972 Lockman succeeded his one-time manager Leo Durocher as manager of the Cubs. When he took over, the Cubs were in fourth place in the National League East. The team responded well to Lockman’s player-friendly leadership and climbed to second place by the end of the season. However, the club reverted to its losing ways in 1973 and 1974. In midseason 1974 Lockman was fired. Under his guidance the club had won 157 games and lost 162. He then moved into the Cubs’ front office and served as general manager until late 1975 and as director of player development until 1989. Later he served in the same capacity and as a special-assignment scout for the Montreal Expos from 1989 to 1993. He joined the Florida Marlins as a scout in 1993.

In the summer of 1951 Lockman married Shirley Elizabeth Conner, the daughter of a neighbor in Charlotte, North Carolina. They had six children: Linda, Cheryl, Kay, Nancy, David, and Robert. They moved to Scottsdale, Arizona, in 1970. Shirley died in 2001 in the 50th year of their marriage. In 2007 Whitey remarried.

In the early spring of 2009 Lockman contracted pulmonary fibrosis. Although confined to the Mayo Clinic Hospital in Phoenix, he was alert and in good spirits until and including the day of his death, March 17, 2009. He was survived by his second wife, Linda Lockman, five children, a stepdaughter, and three grandchildren. He was cremated and the ashes were given to his family or friends.13 His friend and former fellow scout Gary Hughes was with Lockman the day he died and had the sad duty of informing other friends of the death. “What a gentleman.” Hughes said. “He was just such an example of how you should live your life. … I’ve had a lot of big, tough men crying on the phone today.”14

This biography appears in “The Team That Time Won’t Forget: The 1951 New York Giants” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and C. Paul Rogers III.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Rod Nelson for providing information about Lockman’s signing by the Giants in 1943. Thanks also to Bill Nowlin, Jacob Pomrenke, and Paul Rogers for making available additional sources of information about Lockman.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com and numerous publications.

Notes

1 Available records disagree on the order of Lockman’s two given names. Most reference books prefer Carroll Walter. Earlier records tend to favor Walter Carroll. The 1930 and 1940 censuses both show him as Walter C. He signed his 1944 draft registration in a beautiful, flowing script as Walter Carroll Lockman. His Army enlistment papers show him as Walter C. Lockman. The North Carolina birth index lists him as Bentley Carol Lockman. However, an inspection of the original papers shows that his name was entered as Carol and Bentley was added above his name in different handwriting. Ancestry.com shows the name as Walter Carol “Whitey” Lockman.

2 Boomball is something like a cross between baseball and kickball, using a ball that somewhat resembles a soccer ball and having rules similar to those of earlier versions of baseball.

3 Barney Kremenko, in Tom Meany, The Incredible Giants (New York: Barnes, 1955), 197.

4 Kremenko, 189.

5 Brent Kelley, Pastime in Turbulence (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2001), 166.

6 Kit Crissey, interview with Whitey Lockman, May 18, 1973, SABR Oral History Collection.

7 Crissey.

8 Kremenko, 190.

9 Kremenko, 191.

10 Steve Bitker, The Original San Francisco Giants: The Giants of ’58 (Chicago: Sports Publishing, 2001), 117.

11 “Whitey Lockman Dies at 82; Set Up Epic Homer,” New York Times, March 19, 2009.

12 “Whitey Lockman Dies at 82; Set Up Epic Homer.”

13 findagrave.com. Find a Grave Memorial #34966069. Baseball-reference.com reports that he was buried in Paradise Memorial Gardens in Scottsdale, Arizona. Paradise Memorial Gardens contains a cemetery, crematory, and mausoleum.

14 Gordon Edes, “Obituary: Lockman’s Roots Began on Historic Note,” YahooSports, March 19, 2009. https://news.yahoo.com/news/obituary-lockmans-roots-began-historic-073500905–mlb.html?fr=sycsrp_catchall

Full Name

Carroll Walter Lockman

Born

July 25, 1926 at Lowell, NC (USA)

Died

March 17, 2009 at Scottsdale, AZ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.