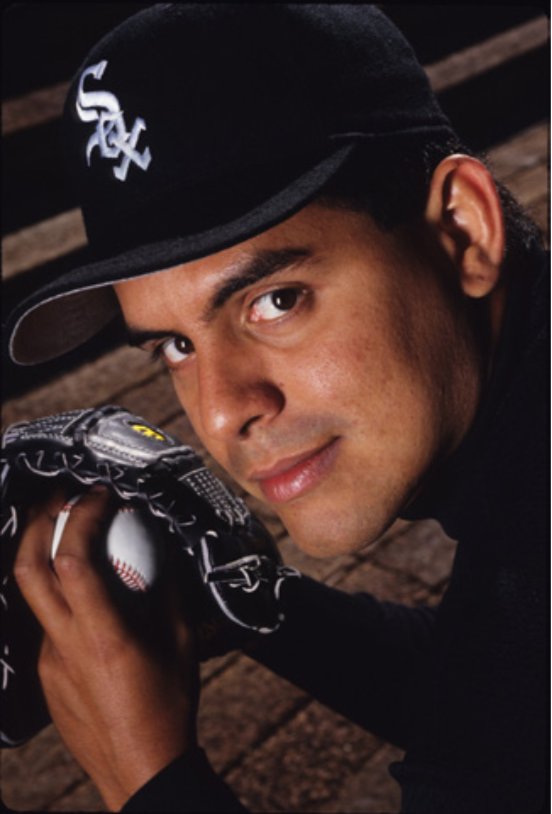

Wilson Alvarez

Wilson was meant to be. The no-hitter he pitched for the White Sox on August 11, 1991, changed not only his life, but also the way a country’s new generation embraced baseball.

Wilson was meant to be. The no-hitter he pitched for the White Sox on August 11, 1991, changed not only his life, but also the way a country’s new generation embraced baseball.

Asked about the game over the years, he would repeat, “It was a gift from God.”1 Indeed, it seems it was.

Wilson Álvarez became the fourth youngest pitcher in history to accomplish the feat.2 He was the 13th Chicago White Sox pitcher to throw a no-hitter, and his was the 14th hitless game in franchise history. It was the first for a Venezuelan pitcher. And this was just his second major-league start.

The world of major-league baseball first heard the name of left-hander Wilson Álvarez in July 1989, when the Texas Rangers called him up for a spot start on July 24. In his native Venezuela, Álvarez was already a well-known name, mostly in Maracaibo, his hometown, where he had been in the news since he was a boy starring in the little leagues.

Wilson Álvarez was born in Maracaibo on March 24, 1970, the son of William Álvarez, an upholsterer, and Ada Álvarez, a homemaker. Maracaibo is one of the most baseball-crazy corners of the world, the place where Luis Aparicio became an idol and where every kid dreams about being a major-leaguer. Wilson and his three brothers, William, Walter, and Willy, were no different. (There was also a daughter, Wendy.)

It was Ada who took the time to take her sons to the Santa Lucía Little League field every weekend for games and during the week for practice.

Maracaibo is the epicenter of the Little League system in Venezuela, home to the Coquivacoa Little League, the first Venezuelan league affiliated with the Williamsport, Pennsylvania-based organization. In 1955 Frank Poteraj, an American oil worker, committed to bring organized baseball for boys to the area and founded the league, encouraging the subsequent affiliation of other leagues. As of 2017, 23 of the 37 affiliated leagues in the country actively operate in the state of Zulia, and of the five Latin American teams that have won the Little League World Series title, two have been from Maracaibo.

It was in these challenging and competitive surroundings that Wilson Álvarez grew up, learned baseball, and began to shine. While in Little League between the ages of 11 and 16, he pitched 12 no-hit games, gaining notoriety as a top prospect.

In August 1984 Venezuela celebrated the induction of Luis Aparicio to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. The National Sports Institute issued a commemorative magazine.3 Aparicio’s picture was on the cover and most of the issue was dedicated to his legacy. The last page, however, showed a picture of 14-year-old lefty Wilson Álvarez, who had recently thrown a 21-strikeout no-hitter in a national youth baseball tournament.

Aparicio’s induction in Cooperstown was celebrated on August 11, 1984. Exactly seven years later, and around the same time in the afternoon that Aparicio made his acceptance speech, the kid from the back cover was pitching a no-hitter, and for one of Aparicio’s old teams, the White Sox.

After the hype surrounding his amateur career, the 16-year-old Álvarez was signed on September 23, 1986, by the Texas Rangers as an international free agent and was assigned to Águilas del Zulia of the Venezuelan Winter League. In his first season, he started one game, had nine appearances as a reliever, and allowed 12 runs in 9⅓ innings pitched, finishing his first professional season with a record of 0-1 and an 11.57 ERA.

A couple months after the winter season Álvarez traveled to his first spring training in the United States and was assigned for 1987 to the White Sox’ team in the Gulf Coast League. He posted a record of 2-5, 5.24 in his first 10 starts. He was promoted to the Class-A South Atlantic League, going 1-5 with a 6.47 ERA in six starts for the Gastonia Rangers. He finished his first year with a combined 3-10 won-lost record and a disastrous rate of 5.2 walks per nine innings.

“Those days were tough,” he recalled. “It was tough to adapt to a new culture, new friends, language, food and all. The expectations were high back home and I felt things were not going on the right direction, although I trusted that I could pitch and do my job.”

Álvarez grew to become 6-feet-1 and 175 pounds.

Álvarez was always a very shy person, very quiet. Some people confused his lethargy with laziness. During his first two years in the minors, the results were disappointing, but only in terms of stats – something not overly significant for a minor leaguer; the “stuff” was there. His fastball was lively; he was working on his command, curveball, and slider.

The level of play in the Venezuelan League was higher than rookie ball and Single-A. During those years, a mix of major leaguers and top-ranked prospects made this winter circuit one of the most competitive. It is not a secret that the aim of Caribbean baseball is winning, not on player development as in the minor leagues.

Between 1987 and 1990 Álvarez’s game was getting shaped by the competitiveness of winter baseball. He became a fan favorite with Zulia, a team managed by Manny Trillo in ’87, Pete Mackanin in ’88 and ’89, and Rubén Amaro Sr. in 1990.

In 1989 Mackanin took the team and his star young arm to another level, winning the league title and the 1989 Caribbean Series in Mazatlán, México. Led by catcher Joe Girardi and first baseman Carlos Quintana, the team also featured top-caliber major-league prospects including Phil Stephenson, Cris Colón, Pete Castellano, Eddie Zambrano, and major-league journeyman infielder Angel Salazar.

Playing with bright major-league prospects and for coaches like Trillo, Amaro, and Mackanin helped shape Álvarez’s character. “Zulia was a very competitive team,” he recalled. “Those guys played with hard-core passion for the game and for the franchise. Most of them were hometown locals just like me and it was a matter of pride to win. It was a completely different scenario than what we were seeing in those years in the minors. The Venezuelan League was about passion. It was tough baseball. Many, many good players were there … major leaguers, foreign players, people wanted us to win and there was a lot of pressure and fun and they had confidence in me, which I always appreciated.”

The Rangers sent Álvarez to Triple-A Oklahoma City for a brief stint in 1988, but he spent most of the season with Class-A Gastonia, where he was 4-11 but recorded a 2.98 ERA. He started 1989 in the Florida State League for the Port Charlotte Rangers, where, going 7-4 with a 2.11 ERA in the first half of the season, he showed at age 19 that his three years of professional experience were really paying off. His strikeout-to-walk ratio improved and his curveball and changeup command was effective after coming back from the Winter League. He was promoted to Double A, joining the Tulsa Drillers of the Texas League the first week of July.

The big-league club was challenging Oakland in the divisional race and after several years the White Sox had a shot at the postseason. They knew their farm system was loaded with great talent from Latin America thanks to the labors of assistant GM Sandy Johnson.

Rangers general manager Tom Grieve decided to start showing off his talent pool by calling up players who could either help or become fodder for trades. In June the White Sox called up 20-year-old Dominican outfielder Sammy Sosa. And on July 24, after just three weeks in Tulsa, Álvarez was called up to start against the Toronto Blue Jays in place of the injured Charlie Hough. The 19-year-old became the first player born in the 1970s to play in the major leagues.

Álvarez’s first pitch, to Junior Félix, was a strike. On his fifth pitch, Félix hit a single to center field. Tony Fernández was up next and he hit a home run to left. On a 2-and-2 count, Kelly Gruber went back-to-back deep to center field. George Bell walked. Fred McGriff got four balls in a row. Manager Bobby Valentine took Álvarez out of the game, bringing in Dominican veteran Cecilio Guante in relief.

The rookie departed after facing five batters and surrendering three hits and two walks for three runs. Having recorded no outs, he carried an earned-run average of infinity.

“Most people thought (calling up Álvarez) was because (White Sox GM Larry Himes) was at the game,” Grieve told the Chicago Tribune. “The purpose of that callup was to win that game and he was the best one we had for that job.”4

“They called me up to show me so they could trade me,” Álvarez declared. “I was devastated. I thought it was going to be almost impossible to get back to the majors. The next day they sent me down back to Tulsa and the day after they told me I was traded to the Chicago White Sox.”

Álvarez took the news badly. His confidence was hurt. The Rangers needed to add a veteran bat for the rest of the season and the White Sox were an aging team with a poor farm system. Chicago sent veteran All-Star Harold Baines and Venezuelan infielder Fred Manrique to Texas for Álvarez, skinny outfielder Sammy Sosa, and infielder Scott Fletcher.

A few days later Álvarez was pitching for the Birmingham Barons of the Double-A Southern League. He pitched just six more games the rest of the season and then returned to Zulia, where his confidence returned with the comfort of playing at home.

The 1990 season offered a fresh start for the lefty and after his solid performance in Venezuela he was sent to Triple-A Vancouver. That year he married Daihanna, who was pregnant; he started the season with a record of 7-7 and an ERA of 6.00. He was demoted to Double-A Birmingham by midseason.

On the personal side, his wife gave birth prematurely to their first child, a boy. After complications from a pulmonary infection, the baby died on August 11, just five days old.

“That was hard. We were so excited for the birth of the baby. I couldn’t concentrate on baseball. Losing a child was something we couldn’t understand and we were both so young and hopeful that all was going to be fine with my career, our family. But it wasn’t.”

Álvarez finished the season with seven more starts in Double A, going 5-1 and improving his ERA to 4.27. Birmingham pitching coach Rick Peterson helped him face his emotional struggles.

By spring training of 1991 Álvarez was coming off his best season in winter ball, having gone 3-3 in nine starts for Zulia with an ERA of 1.38, establishing himself as one of the top hurlers of the circuit at the age of 20. He looked like a veteran on the mound and was ready to prove to the White Sox that he belonged in the majors. His fastball was in the mid-90s, and he had better command of his slider and curveball. The White Sox assigned him again to Birmingham and after 23 starts, he was 10-6 with a 1.83 ERA and 165 strikeouts in 152⅓ innings. The stuff was there and the moment to return to the majors was getting close. The White Sox were reshaping their team, and Álvarez was in their plans.

To ensure that Álvarez was fit for the job, the White Sox called him up on August 11. He would face the Baltimore Orioles that Sunday afternoon at Memorial Stadium. It was his second major-league start.

“I couldn’t believe I was getting back and pitching on the same day when we lost our baby,” he said. “I had a million things on my mind, I was nervous because I was afraid that I was not going to be able to make an out like in 1989. I didn’t know what to think or do because of the chance to pitch back on this level. When we arrived on the bus to the ballpark I realized I had left my bag with all my clothes and equipment at the lobby of the hotel. The team sent a person to get my stuff where my wife was waiting. When the bag arrived I got dressed and ran to the bullpen with the belt on my hand to prepare for the game and only was able to warm up for a half-hour.”

That afternoon the baseball gods were behind Álvarez. Facing a tough Orioles lineup with hitters like Cal Ripken, Randy Milligan, Chris Hoiles, and Dwight Evans, he managed to make outs step-by-step, with his solid fastball, circle change, slider, and splitter. Everything worked just fine. The White Sox scored twice in the top of the first and Álvarez struck out the side, all three swinging, in the bottom of the inning. The White Sox scored two more runs in the second, and after walking Dwight Evans in the second, Álvarez resumed mowing Baltimore batters down. The next baserunner reached on a walk in the sixth. Álvarez walked five batters in all, and his catcher, Ron Karkovice, made an error in the seventh, but Álvarez didn’t give up a hit. The White Sox defense did its part with a memorable sliding catch in the seventh inning by center fielder Lance Johnson that helped preserve the gem. Álvarez had himself a no-hitter.

“He didn’t realize he was there,” recalled teammate and countryman Ozzie Guillén. “I’d heard about his performance in the little leagues in Venezuela and in Chicago we knew him as the kid we got in the Harold Baines trade. I never got to actually know him until that day when we needed a pitcher and he came over for a start. I always think that he didn’t believe he was pitching that day and he just let go all his talent from the mound.”5 It was a historic achievement for a Venezuelan pitcher. The whole country watched the game on television and the no-hitter became a national storyline of pride and greatness – a mark for a whole generation.

For the next seven days, every major newspaper in Venezuela sold out their advertising pages to one company or another, each congratulating Álvarez for his game. Even a month after the game, the congratulatory messages were around – billboards in streets with his picture and graffiti on walls with thank-you messages. Everybody was part of the celebration.

Álvarez was the second major-league pitcher to hurl a no-hitter in his second major-league start. He stayed with the White Sox for the rest of the season and established himself in the pitching rotation. He ended his major-league season with a record of 3-2 in nine starts, with a 3.51 ERA.

After his no-hitter, Venezuelan fans followed every game that Álvarez pitched over the next 12 years, hoping to see another no-hitter. It became part of the fan psyche.

After the season Álvarez went back to Venezuela to pitch for Zulia and was received as a hero in his hometown. For Zulia he became the first winner of the pitching Triple Crown, leading the league in wins (8-0), ERA (1.47), and strikeouts (64). He was named the Pitcher of the Year and led the Águilas to the league championship and a spot in the 1992 Caribbean Series.

After his 8-0 record and extraordinary year of 1991, Álvarez became better known as El Intocable (The Untouchable).

Álvarez started the 1992 season as a reliever for the White Sox but he struggled, in large part due to a walk rate of almost six per nine innings. He joined the rotation in mid-June and ended the season with an ERA of 5.20, starting only 9 games out of 34 appearances. That winter he returned to Venezuela; he pitched six games with a 4.08 ERA.

By this time, major league baseball had become more and more aware of the workload of Latin players and began limiting performances in winter ball for key players. The White Sox saw Álvarez as an important part of their plans, and fans in Venezuela had to adjust to seeing fewer major-league stars.

“I wanted to pitch every year and all season in Venezuela,” said Álvarez. “The (White Sox) considered that pitching in Venezuela was a risk, but also necessary to keep in shape during the off months. For me it was a continual growing but also a matter of pride, to be able to pitch in front of my family and friends and for the team who gave me so much. Even with limitations, I tried by all means to pitch back home.”

Álvarez was excited to pitch in “El Juego de la Chinita,” a celebratory game honoring the Virgin of Chiquinquirá, the patron of Maracaibo. This game has been played on November 18 since 1933; Luis Aparicio made his debut in professional baseball in El Juego in 1953, playing for Gavilanes.

“It was special to pitch that day. It’s a spiritual thing. It’s the energy of the fans. The ballpark is packed with over 25,000 people all excited and being part of the celebration that embraced the city. Those games were special and it was an honor for me and for my family to be in the center of the mound representing what we are,” Álvarez said.

In 1993 Álvarez was a full-time starter for the White Sox alongside Jack McDowell (Cy Young Award winner in 1993), Cuban-American prospect Alex Fernandez, and Jason Bere. This quartet won 67 out of the White Sox’ 92 victories as they clinched the AL West. Álvarez (15-8) led the starters with a 2.95 ERA.

The White Sox advanced to the ALCS, against Álvarez’s nemesis, the Toronto Blue Jays, who won the first two games of the series. Álvarez took the mound for Game Three.

“It was a huge game for me, for all people behind me, and I always remembered when I could not record an out in 1989. It was the time to be the face of my team and step up,” he said.

Álvarez threw a real gem, a complete-game 6-1 win at SkyDome, allowing only seven hits and two walks. The win lifted morale and Chicago won the next game, but couldn’t contain the Blue Jays’ offense in the final two games. The Blue Jays won the ALCS and followed with a World Series victory over the Philadelphia Phillies.

In 1994 Álvarez was named to the American League squad for the All-Star Game. He pitched the bottom of the eighth inning, retiring the side in order. For the season he was 12-8, 3.45.

Álvarez spent 1995 and 1996 as a solid member of the White Sox rotation, starting 64 games. He improved his strikeout-to-walk rate and won 23 games (8-11 and 15-10, with ERAs of 4.32 and 4.22).

At the July trading deadline in 1997, Álvarez was 9-8 with a 3.03 ERA. The White Sox looked revamp the team with a younger roster. It was Álvarez’s final year before free agency. Rather than lose Álvarez the White Sox traded him to the San Francisco Giants along with pitchers Danny Darwin and Roberto Hernández in a nine-player deal.

“I was not comfortable with the Giants,” Álvarez said. It was a difficult change switching leagues. I struggled. I never felt comfortable in the dugout. Roberto and I got into a place where we never felt totally welcome. Barry Bonds was not the nicest person in the world and he was the leader of that clubhouse. Overall it was not a good experience.”

During his time with the White Sox, Álvarez was 67-50 but lost 30 games in which the team scored two or fewer runs. After his stint with the Giants he became one of the most sought-after lefties in baseball. The New York Yankees were a top contender for his services, but he chose to sign with the expansion Tampa Bay Devil Rays for five years and $35 million.

Álvarez said, “Signing with Tampa Bay was a decision my family and I took. We stayed living in the Sarasota area after signing with the White Sox and being close to home was the most important factor in place. My daughters were going to school and I was just several miles from the new ballpark. They also offered me the chance of being the number-one starter in the rotation. It was a new challenge and I took it.”

Álvarez became the first starter in the Devil Rays’ history and threw the first official pitch at Tropicana Field. But his season didn’t go as planned. He ended up with a 6-14 record and an ERA of 4.73. Again run support was lacking, perhaps understandably on an expansion team. Álvarez felt some pressure from fans who were expecting a solid performance from the new team and their highly-prized free agent.

Tampa Bay was an inconsistent team. The Devil Rays had signed big names such as Álvarez, Roberto Hernández, sluggers Fred McGriff and José Canseco, and future Hall of Famer Wade Boggs. The rotation was not deep and the bullpen was inconsistent, and the team finished with a 63-99 record. The Devil Rays improved to 69-93 in their second season. Álvarez was 9-9 (4.22).

Álvarez came back to Venezuela and played winter ball in 1999, winning some key games for Zulia, including five games in the postseason that helped the team reach the finals. Zulia won the title, Álvarez’s fourth title with the team. He pitched the opening game for the 2000 Caribbean Series, but lost the game on unearned runs.

When the 2000 season arrived, expectations were high for the Devil Rays but injuries plagued their roster. Five days before the start of the season, Álvarez was placed on the disabled list with shoulder tendinitis.6 He had to undergo arthroscopic surgery. The 18-month rehab process cost him two seasons; he pretty much had to learn again how to throw a baseball. Returning to the field in 2002, he was able to pitch in only three games before June.

“It was the most frustrating time of my life” Álvarez said. “I didn´t think it was too bad at the beginning but then the recovery was not progressing and the surgery was the option. It was hard for me because I wanted to show fans in Tampa that I could bring something for the team, but my condition was not there. I had to relearn how to pitch, how to gain velocity, how to move my arm. The process is long and painful and sometimes you feel like quitting, but my family supported me at all times to go back and compete. I gave everything I could to Tampa Bay, but the injury came in a very wrong time for me and for the team. I understand the frustration of fans and the organization.”

In 2002 Álvarez was able to pitch only 75 innings in 23 games; it was more of a process to regain confidence in his pitches and to work on a change of approach. He was no longer the power lefty and was about to become a specialist. He had to rely more on location.

By the end of the season Álvarez had reinvented himself as a pitcher, with a fresh shoulder, but the Devil Rays released him. He signed with the Los Angeles Dodgers who planned to use him as a reliever. He turned in a solid performance, posting a record of 6-2 with a 2.37 ERA in 21 games, assuring himself a spot in the bullpen as a lefty specialist and occasional starter. In 2004 he pitched in 40 games, 15 of them as a starter.

After signing a new free-agent contract with the Dodgers after the 2004 season, Álvarez was set back again with shoulder injuries in 2005 and on August 1 he opted for retirement instead of another surgery.

On December 30, 2005, Álvarez pitched one last time for Zulia, taking the mound before a handful of fans in Maracaibo with the team eliminated from contention. He wore his number-47 jersey for the last time and retired the side in one inning of work. It was a sentimental afternoon in honor of a local boy who had reached the highest levels of the game.

After Álvarez’s no-hitter, five more Venezuelan-born pitchers (as of 2017) pitched no-hit games: Anibal Sánchez in 2006 for the Marlins, Carlos Zambrano in 2008 for the Cubs, Johan Santana in 2012 for the Mets, Félix Hernández, a perfect game in 2012 for the Mariners, and Henderson Álvarez in 2013 for the Marlins. (The list should be six: Armando Galarraga lost his perfect game for the Tigers in 2010 when umpire Jim Joyce incorrectly called a batter safe at first base.7) For each one of these pitchers, Wilson Álvarez was an inspiration due both to his successful 14-year major-league career and the impact the no-hitter had in a baseball crazed-country.

Wilson Álvarez was the first Venezuelan pitcher with over 100 wins in the major leagues, compiling a record of 102-92 with a 3.96 ERA in 355 games. He made the All-Star team in 1994. In Venezuela he pitched for 12 seasons with a record of 29-18 and a career ERA of 2.49. He was elected to the Venezuelan Baseball Hall of Fame in 2011 and the Caribbean Series Hall of Fame in 2010.

After retiring Álvarez became the pitching coach for the Gulf Coast League Orioles (Rookie) near his residence in Sarasota, Florida. He and his wife, Daihanna, had three daughters, Vivianna, Vanessa, and Valentina. He has returned to the Venezuelan League as a pitching coach for Caribes de Anzoátegui and Águilas del Zulia, where he remained a fan favorite and an icon of the team, being part of four of the five titles in the history of this franchise.

Álvarez reflected, “When you retire it is like all that attention that you had, is gone, from one day to another and it never comes back. So another stage of your life begins and you discover it while still being young.”8

In the 2016-17 season, Álvarez as pitching coach helped guide a young staff to a solid season. Zulia went to the finals for the first time since 2000 and won the title in six games over Cardenales de Lara. In the Caribbean Series the team lost to the Criollos de Caguas of Puerto Rico in the semifinals.

Álvarez’s number-47 jersey remained one of the top sellers among fans, and on December 14, 2016, the team officially retired his number.

“This is the most important moment of my life because I’m here with my family, my teammates, my friends and my beloved team,” Álvarez responded.9 His parents and siblings were at the ceremony, after which he threw out the ceremonial first pitch.

Álvarez established a music label, “47Music,” run by his wife, to support new artists in the Latin Pop genre.

Despite the passage of time, new generations of fans in Venezuela still hear the echoes from August 11, 1991, when a country shouted together: “Wilson threw a no-hitter!”

From Álvarez: “It was a gift from God.”

Sources

This article draws on personal interviews and both on- and off-record conversations with Wilson Alvarez between 1995 and 2017.

The author also consulted ¡A La Carga!, the official magazine of Águilas del Zulia (Maracaibo, Venezuela: Tripleplay Sports Productions, 1997-2002), Baseball Zone (Maracaibo: Tripleplay Sports Productions, March 2001), Diario Panorama (Maracaibo) and the Dallas Morning News.

Notes

1 All quotations by Wilson Álvarez are from interviews with the author unless otherwise attributed.

2 The younger ones were Amos Rusie (7,367 days), John Ward (7,411 days), and Vida Blue (7,725 days.) Alvarez was 7,810 days old.

3 Revista IND. (Caracas, August 1984).

4 Alan Solomon, “Alvarez: The Making of the Sox’ No-Hit Kid,” Chicago Tribune, August 13, 1991: B1.

5 Conversation with Ozzie Guillén about Álvarez’s no-hitter, March 24, 2017.

6 articles.latimes.com/2000/apr/01/sports/sp-14936.

7 See Andres Galarraga and Jim Joyce, with Daniel Paisner, Nobody’s Perfect (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2011).

8 eljuegoperfecto.blogspot.com/2010_01_01_archive.html.

9 noticiaaldia.com/2016/12/wilson-alvarez-este-es-el-momento-mas-importante.

Full Name

Wilson Eduardo Alvarez Fuenmayor

Born

March 24, 1970 at Maracaibo, Zulia (Venezuela)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.