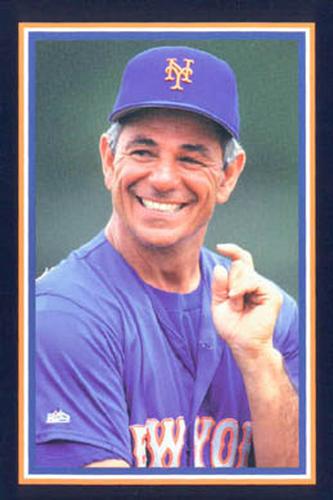

Bobby Valentine

Bobby Valentine played in the majors for 10 years. After his playing career, he became one of the most colorful managers in baseball during the last decade of the 20th century. Valentine was always candid and outspoken throughout his managerial career.

Bobby Valentine played in the majors for 10 years. After his playing career, he became one of the most colorful managers in baseball during the last decade of the 20th century. Valentine was always candid and outspoken throughout his managerial career.

Robert James Valentine was born on May 13, 1950, in Stamford, Connecticut. His parents were Joseph and Grace Valentine. Valentine’s father was a carpenter who supported the family by taking various jobs in Stamford. Valentine lived with his parents and older brother Joe in a four-room house on Melrose Place in Stamford.

Valentine grew up playing ball in the street with neighborhood friends until he was old enough to ride his bike to Southfield Park. “Southfield Park was the place to be,” he remembered. “I’d try to round up my cousin Donnie, who was the exact same age as I was, and I’d put as many baseball gloves as I could find on the handlebars and go. We’d play baseball, wiffle ball, football, kickball. Anything with a ball.”1

His brother remembers taking him to Southfield Park with him. When the other kids first saw Valentine, they wondered why he was there. But that didn’t last long. “Bobby was always faster and better than everyone, even as a 10-year-old going against 14-year-olds,” his brother said. “You just had to see it. He was special. The second time I brought him to the park, when we chose up sides, my older friends all wanted to take him first.”2

Valentine continued to play baseball in the neighborhood until he attended Cloonan Junior High School. When Valentine entered ninth grade, his school closed down. “Boy, was I lucky they did that. Because instead of being a ninth-grader at Cloonan Junior High School in Stamford, I was a high schooler at Rippowam High School.”3 He moved in with his grandparents so he could attend the shiny new Rippowam High School.

After Valentine arrived at Rippowan, he quickly became a two-sport star, playing football and baseball. “I was able to play on the football team as a ninth-grader, so the first game of my sophomore year not only was I able to know the plays, I was able to start and I was able to score four touchdowns, and I was able to play on a state championship team and be All-State running back.”4

Valentine had an outstanding high school baseball and football career. He is the only three-time All-State football player in Connecticut history.5 He was so good at football that he had numerous scholarship offers. Southern California coach John McKay was so impressed that he told Valentine that he would replace OJ Simpson in the USC backfield and win the Heisman Trophy.6

Valentine also garnered attention on the diamond. He caught the eye of a baseball scout for the Cape Cod League. “I had one of those crazy games,” Valentine recalled years later. “I hit home runs. I ran the bases. I made plays. After the game, this little 24-year-old Italian guy came over to my mom and dad and said, ‘I really like the way your kid plays. I want to take care of him for the summer.’”7

After playing in the Cape Cod league, Valentine’s play was good enough to give him the opportunity to play both baseball and football at USC. It was during his visit to southern California that Valentine first met future Dodger manager Tommy Lasorda.

As Valentine tells it, “While I was there, someone sat down next to me and said, ‘Don’t turn around. I’m not really talking to you. I’m not supposed to be talking to you. But I know who you are, and I want you to know we really like what you’re doing.’” The individual “handed me a transistor radio, and on it was the logo of the Dodgers. (Lasorda’s card was inside it. He was a scout for the Dodgers).”8

Valentine was drafted by the Los Angeles Dodgers as the fifth pick in the first round of the 1968 MLB June Amateur Draft. He was considered the prize of the Dodgers draft class that year, one that included future major league stars Steve Garvey, Ron Cey, Bill Buckner, and Davey Lopes. Valentine had to make a choice and chose baseball.

The Dodgers sent Valentine to the Ogden Dodgers in the rookie level Pioneer League after the draft. He played well, hitting .281 with a .460 slugging percentage. Valentine also won the league MVP award.

The following year, Valentine was so impressive in spring training that the Dodgers jumped him all the way to the Triple-A Spokane Indians at the tender age of 19. He struggled at the plate against the stiffer competition. Valentine batted .259/.318/.353 with three homers. But he was an important part of the Spokane offense as he stole 34 bases, drew 32 walks, and struck out just 57 times in 402 at-bats. The Dodgers moved him from the outfield to shortstop. It was a challenging transition; Valentine made 38 errors. He was called up to the majors in September and appeared in three games as a pinch-runner.

Valentine returned to Spokane in 1970. He tore up the league that year with a .340/.389/.522 season. He hit 39 doubles, 16 triples, and 14 homers. Valentine so clearly dominated the league that he won the Pacific Coast League MVP award. Although he struggled defensively, making 54 errors, his offensive production kept his future looking bright.

Although the Dodgers did not call him at the end of 1970, Valentine was brought up to the Dodgers shortly after the season began in 1971. He was used primarily as a utility player, batting .249/.287/.310 in 281 at-bats over 101 games. The Dodgers played him at shortstop, third base, second base, as well as the outfield.

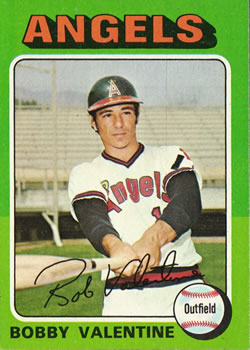

Valentine improved offensively in 1972. He hit .274/.319/.335 in 391 at-bats. The Dodgers continued to use him at multiple positions. When the Dodgers decided to commit to other players, Valentine was traded to the California Angels on November 28, 1972. Valentine went to the Angels along with Billy Grabarkewitz, Frank Robinson, Bill Singer and Mike Strahler, while the Dodgers acquired Ken McMullen and Andy Messersmith.

He got off to a good start in the American League in 1973, hitting .302/.323/.397 for the Angels when the season started. But Valentine’s season ended on May 17 when he suffered a season-ending injury. Valentine attempted to make a leaping catch to rob the Athletics’ Dick Green of a home run and his spikes got caught in the outfield’s chain link fence. He suffered a multiple compound fracture in his right leg just above the ankle.

Valentine missed the rest of the 1973 season. His injury never healed properly and his ankle was permanently bent in the wrong direction, costing him a great deal of speed and athleticism. He returned in 1974 and made 414 plate appearances in the utility role, the second most of his career. He batted .261/.308/.329 with three home runs and 39 RBIs.

Valentine spent most of 1975 in the minors where he split time between the Charleston (West Virginia) Charlies of the International League and the Salt Lake City Gulls of the Pacific Coast League. The Angels called him up in August and Valentine played in 26 games before the Angels traded him. On September 17, 1975, Valentine and Rudy Meoli were sent to the San Diego Padres for Gary Ross. Valentine appeared in seven games for the Padres as the season drew to a close, hitting .133 in 15 at-bats.

Valentine spent most of 1975 in the minors where he split time between the Charleston (West Virginia) Charlies of the International League and the Salt Lake City Gulls of the Pacific Coast League. The Angels called him up in August and Valentine played in 26 games before the Angels traded him. On September 17, 1975, Valentine and Rudy Meoli were sent to the San Diego Padres for Gary Ross. Valentine appeared in seven games for the Padres as the season drew to a close, hitting .133 in 15 at-bats.

The Padres dispatched Valentine to their Triple-A club, the Hawaii Islanders in the Pacific Coast League, in 1976. He batted .304 /.375 /.471 while hitting 23 doubles, 13 home runs, and knocking in 89 runs in 120 games. Valentine was brought back to the majors in September and appeared in 15 games.

Valentine started the 1977 season with the Padres. On June 15, 1977, the Mets completed a multi-team trade known as the “Midnight Massacre.” The Mets sent their team icon, Tom Seaver, to the Cincinnati Reds for Pat Zachry, Doug Flynn, Steve Henderson, and Dan Norman. Dave Kingman was sent to the San Diego Padres for minor league pitcher Paul Siebert and Valentine, while Mike Phillips went to the St. Louis Cardinals for Joel Youngblood.

The Mets used Valentine sparingly the following two seasons. He appeared in just 111 games and batted .222 during that time, garnering 21 RBIs. The Mets released him during spring training in 1979.

Valentine signed with the Seattle Mariners two weeks later. He continued to serve in a utility role, including his first appearance as a catcher. After the season, Valentine was granted free agency and he retired from baseball.

After retiring, Valentine returned to Stamford. He opened his first restaurant, Bobby Valentine’s Sports Gallery Café, in 1980. Valentine owned and operated the restaurant for the next 36 years. “It’s called Sports Gallery because all the memorabilia was on display. I have a lot of stuff displayed in my home, but [much of it is here].”9

When his career was drawing to an end, Valentine sought out the advice of Lasorda, his former manager. “Tommy had told me to start thinking about how I could stay in baseball. That’s what I wanted to do,” he said.10 Valentine eventually joined the Padres as a minor-league infield instructor.

Valentine moved to the Mets in 1982 as a minor-league instructor. He became the Mets third base coach in 1983, serving under managers George Bamberger and later Frank Howard. Valentine remained as the team’s third base coach in 1984 after Davey Johnson became the team’s new manager.

While he was coaching the Mets, Valentine began to sell himself as a possible manager. He started applying to teams that had fired their manager. Before the Rangers hired him, Valentine phoned their front office to offer his services. He did the same when the Boston Red Sox and Montreal Expos were between managers as well. “I let them know I was available,” he said.11

He left the Mets early in the 1985 season when the Texas Rangers hired him to be their manager after firing Doug Rader. When he was hired, Valentine was the youngest manager in the major leagues at the time. The Rangers were 9-23 and continued to struggle during his first season at the helm. They went 53–76 under his leadership in 1985, finishing with an overall record of 62–99.

Valentine began to use many of the lessons that he had picked up from observing managers during his playing days. He talked about times when he directly questioned his manager’s strategy when he was sitting on the bench during a game. One time he burst out, “We should be bunting now,” causing his manger to glare at him. “It bothered Walter Alston and Joe Torre a little. That’s why I try to let my players know my thinking.”12

The Rangers finished second in the American League West during Valentine’s sophomore season, finishing with a record of 87–75. Valentine finished second for AL Manager of the Year that year. Reflecting the team’s success, Valentine said: “What I want is to develop tradition here. Teams that have tradition have a definite edge. We have to be more than just the baseball team in town. I want players to be proud to put on a Ranger uniform.”13

Fans were hoping for more success after the 1986 season, but his Rangers fell back into sixth place the following two seasons. The team had a record of 75-87 in 1987 and 70-91 in 1988 to finish in sixth place both seasons.

The Rangers improved and finished with identical winning records of 83-79 in 1989 and 1990. But they still remained mired in the middle of the pack of the American League West. They came in fourth in their division in 1989 and third in 1990. Although Valentine’s Rangers improved slightly in 1991 to 85-77, they still finished third in their division.

Valentine worked as an on-field analyst for NBC during the 1989 ALCS. The Athletics accused Valentine of tipping off the Blue Jays when Toronto asked the league to investigate whether or not Dennis Eckersley had used an illegal substance. Valentine was so incensed by the accusation that he sent telegrams to Eckersley and A’s manager Tony La Russa demanding apologies.14

Halfway through the 1992 season, Valentine was fired by Rangers Managing Partner George W. Bush. At the time the team had a record of 45–41. “Six-and-a-half games back and not playing very well in a season we thought we ought to be in contention. I think we were losing ground [and needed to make a change],” Bush said about Valentine’s release.15

At the time of his firing, Valentine was the third longest tenured manager in the majors. When asked about the firing, he told reporters, “I’m not ready to move away from this team right now with my heart, my mind or my talent. We might stay here and watch them win the World Series.”16

He left the Rangers with a 581-605 record and the club mark for wins, losses and games managed. Valentine felt like he had improved the Rangers during his tenure with the team, saying “I don’t think anybody would’ve done better than I did while I was here. People are going to look back and say in 1985, this is where the Texas Rangers were and in 1992, this is where they were when he left. I think people are going to say that’s one hell of a job.”17

Valentine joined the Reds staff in 1993. He was the third base coach for Johnson, his former Mets manager, who was now managing the Reds. The following year, Valentine returned to the Mets organization when he became the manager of their Triple-A affiliate, the Norfolk Tides. The team struggled that season and finished with a 67-75 record in the International League.

After the season, Valentine was recruited by former Tokyo Giants shortstop Tatsuro Hirooka to come to Japan and manage the Chiba Lotte Marines. He became the first major league manager to manage a team in Japan. Although he managed the Marines to a 69-58 mark, he was eventually released. Valentine tried to bring his Western approach to Japanese baseball and it didn’t work.

“When he was a manager of a minor-league team, Valentine was very eager to work closely with players. So I asked him to do the same in Japan. But he managed the weak Lotte Marines as if he were a major-league manager. This was, I think, the biggest problem we had,” Hirooka said at the end of the season.18

Valentine tried to bring what he learned during his major league career to Japan. He said that his ideas were scrutinized closely in Japan. He had to prove that all of his changes, such as monitoring the pitch count, worked. “Everything I thought I knew about baseball was now being challenged. Things that are taken for granted [in the U.S.] had to be explained [in Japan].19

After he was released from the Marines, Valentine came back to the states for a second stint as the manager of the Tides. “I had just put my suitcases on the floor and the phone rang,” he said. “[Mets assistant general manager] Steve [Phillips] wanted to know if I wanted to manage the Tides. I said, ‘I’d walk there to take that job.’”20

Valentine managed the Tides to a 76-57 record before he was called up to take over the Mets near the end of the 1996 season. The Mets had fired Dallas Green and hoped that Valentine would make some improvements since he knew the younger players. At the time, Mets General Manager Joe McIlvaine said, “Our hope with this change is that the younger players can begin to blossom more.”21 The Mets went 12-19 after Valentine was hired. He was given a contract to manage the club the following year.

The Mets believed that Valentine had become a better manager since he left the Rangers. Although he said that he was nervous about taking the job, he also spoke about how he was approaching the job differently. “When I was a young manager, I thought everybody listened to every word I said, and everything I said would be done. When I managed that one year in Japan, I realized how important it was to be understood. Now I say to people, ‘You weren’t listening to me.’”22

Valentine led the Mets to the first of two consecutive 88-74 records in 1997. The team finished third in their division in 1997 and second in 1998. The 1998 team had a chance to make the playoffs before they lost their last five games of the season.

Valentine, who had brought a positive attitude to the team since being hired as manager, was extremely disappointed when the team was eliminated. “I don’t know what happened. If I knew, I would have done something about it. That’s my frustration about it. Everything I tried didn’t work. There should have been something.”23

The Mets won 97 games in 1999 yet still finished in second place in the National League East as the Atlanta Braves won 103 games. Valentine made the news several times that season. On June 9, Valentine was ejected in the 12th inning in a home game against the Toronto Blue Jays for arguing an interference call. He returned to the dugout a short time later wearing glasses and a fake mustache made of eye black. His antics earned him a two-game suspension and a $5,000 fine from Major League Baseball. “I wasn’t fooling anyone with that disguise,” he said later. “This had absolutely nothing to do with the umpires. I did it to lighten up the team.”24 The stunt may have worked, though…the Mets won in the 14th on a walk-off single by Rey Ordóñez.

Early in the season when the team was struggling, the Mets fired three of Valentine’s coaches. Valentine was asked about their 27-28 record. He told reporters, “In the next 55 games, if we’re not better, I shouldn’t be the manager.”25 The team went on to have a 39-15 after his statement to make the postseason for the first time in his managerial career.

After winning the wild card and defeating Arizona in the Division Series, the Mets eventually fell to the Atlanta Braves, their division rivals, in the NLCS. The series went to six games with the Braves winning the clincher in extra innings. After the Mets lost, Valentine had nothing but praise for his team’s efforts: “I’m going to take some time during the winter to watch these games and try to enjoy them like millions of people got to enjoy them. They were fabulous games. We gave everything we had.”26

Valentine almost got fired just as the 2000 season was beginning. He spoke to students at the Wharton Business School and made some controversial remarks about Mets players and the team’s management. When the remarks leaked out, Valentine was unusually quiet about it beyond reporting that he spoke to each player afterwards.27 As it turned out, some of the comments were fabricated by one of the student attendees to spice up his web page and amuse his audience.28

The Mets finished second in the NL East in 2000, the third time that they failed to nudge the Braves out of their dominant position at the top of the division. The Mets expected to face their rivals in the postseason but the Braves lost to the Cardinals in the NLDS. Instead The Mets faced their pre-wildcard rivals in the NLCS and beat them in five games.

The Mets victory set up the first “Subway Series” in New York since 1956, as they faced the crosstown Yankees in a battle to determine the World Championship. In a series that was filled with lots of drama, the Yankees outlasted Valentine’s Mets, winning the series, 4-1. “The Yankees are a little better team,” Valentine said when the series was over. “That’s the reality of the situation.”29

After he returned the Mets to the World Series for the first time since 1986, Valentine remained as the Mets manager. When the team struggled during the 2001 season, the Mets once again fired three of Valentine’s coaches. This came after the team lost their eighth consecutive game on June 6. It was longest losing streak since Valentine had taken the helm of the Mets. Valentine disagreed with the decision but stayed at his post. The Mets eventually finished with an 82-80 record, dropping to third place in their division.

After the tragedy of September 11, the Mets returned home on September 21 to play the first baseball games in New York since the tragedy. “It was really emotional, you know, and it was filled with symbolic gestures. But nothing could have set the tone more properly than Mike [Piazza‘s line drive over the left-field fence that I think really began to allow people to return to normalcy.”30 Valentine won the 2001 Branch Rickey award for his efforts to raise money for victims of the September 11 attacks.

The Mets continued to struggle in 2002. In August, they lost all 12 games that they played at home. When the team finished in the cellar, Mets owner Fred Wilpon fired Valentine, stating that “[t]he performance of the team, especially in the last two months of the season, was extremely disappointing.”31

Valentine returned to Japan for his second stint as manager of the Chiba Lotte Marines in 2004. He led the Marines to their first Pacific League pennant in 31 years after emerging victorious in a close playoff with the Fukuoka SoftBank Hawks. The Marines would go on to win the Japan Series in a four-game sweep of the Hanshin Tigers, the Marines first championship since 1974.

Valentine remained with the Marines through 2009. He had winning records every year but his final one. His managerial style was different this time. Valentine changed the way that Japanese players approached the game and humanized the players, which was a major challenge due to the nature of Japanese baseball. He won the Matsutaro Shoriki Award in 2005, the first foreigner to win this recognition. The award is given annually to the player or manager who contributed the most to Japanese baseball.

After returning from Japan, Valentine returned to Stamford to run his restaurants. He became the honorary Director of Public Safety in Stamford in 2011. Valentine worked as a baseball analyst for ESPN in 2009 and 2010.

The Boston Red Sox hired Valentine as their manager in 2012. The Red Sox finished 69-93 that year and he was fired at the end of the season. Valentine had several public disagreements with the players throughout the season and never had the full support of management.32 In 2017, retired red Sox icon David Ortiz published his autobiography, Papi: My Story, in which he called his manager “arrogant,” “disrespectful,” “irrational,” “clueless,” and “aggravating as hell.”33 The former manager fired back, saying, “Obviously, David didn’t even understand what was going on.”34

Valentine became the athletic director at Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, Connecticut in 2013. The university’s sports program experienced success under his leadership. He also raised money to improve the various sporting venues at the university. He told his coaches to think of his role as athletic director in this following way: “I am like a continental breakfast at your hotel. I am there if you need me. But you don’t have to eat breakfast, if you don’t want to.”35

Valentine married Mary Branca, the daughter of former Brooklyn Dodgers pitcher Ralph Branca, on January 8, 1977. They have one son, Bobby Jr., who was born on April 23, 1985.

Valentine, who was known as “Bobby V” during most of his managerial career, may not have won a World Series but he was definitely one of the more colorful managers of his time. Valentine always gave his best during his long career. “When I do something, I try to do something that when I’m through doing it, it’s a little better than when I started doing it. And I don’t think I’ve been anywhere in baseball yet where when I was there, that they were worse after I left.”36

Last revised: October 2, 2018

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by David Lippman and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also used Baseball-Reference.com, Baseball-Almanac.com, and Retrosheet.org websites for player, team, and season pages, and other pertinent material.

Notes

1 Camilla Herrera, “Growing Up in Stamford,” Ilovefc.com, September 2, 2014.

2 Bill Pennington, “Valentine Reunited With Baseball Through Luck and Loyalty,” New York Times, February 17, 2012.

3 Ken Borsuk, “Bobby Valentine talks about the importance of luck,” CT Post.com, November 16, 2016.

4 Ibid.

5 Paul Post, “Bobby Valentine Reflects on His Time in Baseball,” Sports Collectors Digest, March 14, 2016.

6 Pennington.

7 Borsuk.

8 Ibid.

9 Post.

10 Dave Anderson, “Bobby Valentine Returns,” New York Times, July 11, 1985.

11 Anderson.

12 Ibid.

13 Dan Baldwin, “The Second Summer of Bobby Valentine,” D Magazine, April 1987.

14 “Blue Jays Claim Video Shows Eckersley Trying to Hide Something in His Uniform,” Los Angeles Times, October 13, 1989.

15 “He Isn’t Rangers’ Valentine,” Los Angeles Times, July 10, 1992.

16 Ibid.

17 Jaime Aron, “Rangers Run Out of Patience, Give Bobby Valentine the Axe,” Deseret News, July 10, 1992.

18 Phil Rogers, “A Sad Sayonara For Valentine,” Chicago Tribune, March 26, 2000.

19 Ibid.

20 Chris Foster, “Valentine’s Vision Didn’t Translate Into Japanese,” Los Angeles Times, July 6, 1996.

21 “Mets Fire Green, Hire Valentine,” Los Angeles Times, August 27, 1996.

22 George Vecsey, “Valentine Earned His Second Shot.” New York Times, August 28, 1996.

23 Jason Diamos, “Mets Lay Their Final Egg, And It Tastes Awful,” New York Times, September 28, 1998.

24 Chris Littman, “Fifteen years ago, Bobby Valentine broke out a dugout disguise, Sporting News, June 9, 2014.

25 Murray Chass, “Win or Lose, Valentine Still Carries a Burden,” New York Times, August 7,1999.

26 Dave Sheinin, “Braves Walk Past Mets to Reach World Series, 10-9,” Washington Post, October 20, 1999.

27 Frank Gray, “10 Most Outrageous Bobby Valentine Manager Moments, Bleacher Report.com, December 5, 2011.

28 Howard Altman, “The Whartongate Affair,” My CityPaper, April 20-27, 2000

29 Tyler Kepner, “That Was Close: Mets Thwarted by Yanks’ Use of Inches and Seconds,” New York Times, October 29, 2000.

30 “Bobby Valentine Reflects On Mets’ Role Following 9/11,” NewYork.CBSLocal.com, September 11, 2013.

31 Rafael Hermoso, “Mets Fire Valentine to Close Out a Dismal Season,” New York Times, October 1, 2002.

32 Hunter Felt, “Boston Red Sox fire Bobby Valentine: the end of an error,” The Guardian, October 4, 2012.

33 ESPN, “David Ortiz rakes Bobby Valentine over coals in new book,” ESPN, May 12, 2017.

34 Evan Dreilich, “Bobby Valentine fires back: David Oritz ‘didn’t even understand what was going on,’” NBC Sports Boston, May 11, 2017.

35 John Altavilla, “As Athletic Director At Sacred Heart, Bobby Valentine’s Life Takes Another New Direction,” Hartford Courant, December 24, 2017.

36 Tyler Kepner, “Full Transcript: Bobby Valentine Interview,” New York Times, March 3, 2007.

Full Name

Robert John Valentine

Born

May 13, 1950 at Stamford, CT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.