Chuck Connors

Chuck Connors was a career minor-league ballplayer who played portions of two seasons in the major leagues, with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1949 and Chicago Cubs in 1951. Connors gained greater fame as one of the very few ballplayers who was a successful actor in his post-baseball career, best known for his role as Lucas McCain in the TV show The Rifleman. He also appeared in more than 50 movies during his lengthy acting career. Connors was also one of the few men who played both major-league baseball and basketball (with the Boston Celtics in 1946-47).

“I owe baseball all that I have and much of what I hope to have,” Connors said in 1953 when he retired as a ballplayer. “Baseball made my entrance to the film industry immeasurably easier than I could have made it alone. To the greatest game in the world I shall be eternally in debt.”1 For Connors, the turning point in his life came during spring training in 1951 when the Chicago Cubs demoted him to their Los Angeles Angels farm club in the Pacific Coast League. “Greatest break I ever got,” Connors said in 1954. “I’m out there right in the middle of the movie business where, if a guy has anything, he’s got the chance to break in.”2

Kevin Joseph Aloysius Connors was born on April 10, 1921, in Brooklyn, New York. He was the only son of Allan and Marcella Connors, Irish natives who came to the United States via Newfoundland. Connors had one sibling, his sister Gloria. Connors grew up in the Bay Ridge section of Brooklyn, where his parents struggled to eke out a living during the Great Depression of the 1930s. His father was unemployed for much of the decade, as his mother supported the family by scrubbing floors in office buildings; his father eventually found work as a night watchman. Connors said that growing up poor in his pre-adolescent years motivated him to work hard to achieve success as a ballplayer and later as an actor.

While he attended public schools as a youngster, Connors played on the sports teams sponsored by a local boys club, the Bay Ridge Celtics. John Flynn, who coached the teams, helped Connors gain a sports scholarship to Adelphi Academy, a private high school in Brooklyn, where he played football, basketball, and baseball. In his senior year at Adelphi, Connors was named the first baseman on the Brooklyn Eagle all-scholastic baseball team. “Because of baseball, I got a good education,” Connors said later in life. “The coach [at Adelphi] was a former Southeastern Conference heavyweight boxing champion, Hollis Botts. He was a first baseman playing semi-pro ball on the weekends and coaching our team, so I was in good hands, both in sports and in school work.”3

Following his graduation from Adelphi in June 1940, Connors pursued his dream to play for his hometown Brooklyn Dodgers when he signed a minor-league contract with the Dodgers. The Brooklyn Eagle gushed that it had “spotted a successor to Dolph Camilli,” then the incumbent Dodgers first baseman, in the first of many rosy forecasts for Connors to achieve greatness with the Dodgers.4 The Dodgers assigned Connors to their Newport, Arkansas, farm team at the bottom of the minor-league ladder, the Class-D Northeast Arkansas League. Connors played just four games for Newport, batting 1-for-11, before he changed his mind about professional baseball in favor of playing sports in college.

After he voluntarily retired from baseball following his short stint in the Dodgers organization, Connors attended Seton Hall College on a baseball scholarship. He played first base on the undefeated Seton Hall baseball team in the spring of 1942, which compiled an 11-0 record. A highlight for Connors that season was Seton Hall’s 6–5 come-from-behind victory over Fordham on May 11, when Seton Hall scored three runs in the bottom of the ninth inning to win. As reported in the New York Times the next day, Seton Hall tied the score in that ninth inning when “Lacika scored on Connors’ Texas Leaguer.”

Although Connors often voiced an “aw shucks” attitude about his lack of formal training as an actor, his Seton Hall education provided the foundation for his oratory skills. After being goaded into participating in a declamatory contest, he chose to recite Vachel Lindsay’s poem “The Congo,” which was a complex verse concerning Mumbo-Jumbo the God of the Congo. When the judges declared Connors the winner, he was hooked on the performing arts.

Connors also played varsity basketball at Seton Hall during the winter of 1941-42. He was the backup center on the team led by Bob Davies, who went on to a stellar career as a pro player and enshrinement in the Basketball Hall of Fame. Seton Hall coach John “Honey” Russell inserted Connors into several games that winter to spell starting center Ken Pine. Connors scored a career-high six points on December 30, 1941, in Seton Hall’s 59-15 rout of Maryland. “I wasn’t a bad basketball player, but I was far from the world’s greatest,” Connors told biographer David Fury. “Good defense, no offense, that was me.”5 In 1942, the lanky Connors, who stood 6-foot-6, had more promise as a baseball player than as a basketball player, especially after he hit .360 for the Burlington, Vermont, ball club in the semi-pro Northern League during the summer of 1941.

During the summer of 1942, Connors wound up in the minor-league organization of the New York Yankees. The story goes that famed Yankees scout Paul Krichell signed Connors to a minor-league contract after he spotted his name on a list of unprotected minor-league players. Krichell may have seen Connors play for Seton Hall in nearby South Orange, New Jersey (other stories have Krichell scouting him at Adelphi and even arranging for his scholarship to Seton Hall.) However, the Yankees signed Connors in June of 1942 after he played for the Fraser Stars in Lynn, Massachusetts, a ball club in the semi-pro New England League. Connors, whose “work in college circles has been so outstanding that a number of big-league clubs are seeking his services,” played only three weeks in Lynn before signing with the Yankees.6 Why Connors did not return to his beloved Brooklyn Dodgers is unknown. The Yankees assigned Connors to their Norfolk, Virginia, farm club in the Class-B Piedmont League, where he batted .264 in 72 games.

In October 1942 Connors enlisted in the Army, where he spent the next three years state-side as a tank training instructor while the United States fought World War II. After his initial assignment to Camp Campbell in Kentucky, Connors was assigned to West Point, 50 miles north of his native Brooklyn. On weekends during the warm weather, Connors played semi-pro baseball in the New York City area, often with the Bushwick team in Brooklyn. During the colder months, he played pro basketball in the American Basketball League for the Brooklyn Indians (1943-44), Wilmington Bombers (1944-45), and Paterson Crescents (1945-46). Connors became more of a scorer during his wartime basketball years, averaging 6.1 points per game in 27 games for Wilmington and 8.8 points per game in 18 games for Paterson. During the war years, Connors concluded that he could make a decent living postwar as a year-round professional athlete, playing baseball from spring until fall and basketball during the winter. His plan was not all that unusual for the time period, because many athletes played multiple professional sports in the 1930s and 1940s.

In the war years, Connors also acquired the nickname “Chuck,” which soon usurped his given name Kevin. The oft-told story that the nickname originated from his Seton Hall days, where first-baseman Connors was fond of saying to his infielders, “Chuck it to me, baby. Chuck it to me!” is likely apocryphal.7 This story was told by his sister Gloria, in a 1997 biography of Connors. More probable is the explanation that Connors gave in the early 1980s: “They called me Chuck when I started playing baseball because they thought Kevin was effeminate.”8 Since its first published instance was in 1945, the nickname came from his days in semi-pro baseball.9 In 1949 the Brooklyn Eagle reported that Connors was called Chuck “after the old Bowery character of the same name,” which makes sense since Connors played semi-pro baseball mostly in the New York City area.10 The original Chuck Connors, a talkative, shadowy character that was a political boss, was immortalized in the 1933 movie The Bowery, where Wallace Beery played tough-guy Connors in the rough-and-tumble world of the Lower East Side.11 Chuck was the perfect nickname for a hard-nosed baseball player.

After Connors was discharged from the Army in February 1946, he immediately joined the Rochester Royals of the National Basketball League, which had greater stature than did the ABL. Connors played in 14 games for the Royals, scoring 28 points, before he left the club in early March to go to baseball spring training with the Yankees. Rochester went on to win the NBL title that spring, establishing a lengthy pattern of Connors playing on championship teams as a postwar athlete.

Connors found his way back to the Brooklyn Dodgers organization during spring training of 1946 after the Yankees asked waivers on him to move him down from their top minor-league farm club in Newark, New Jersey. Brooklyn picked up Connors off the waiver wire and assigned him to the Dodgers farm club in Newport News, Virginia, of the Class-B Piedmont League. Connors hit 17 home runs in 1946 to lead the Piedmont League and establish himself as a prime prospect to be the first baseman for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Newport News won the Piedmont League playoffs, the first of four consecutive championship minor-league baseball teams that Connors played on.

Returning to professional basketball in the fall of 1946, Connors played in the Basketball Association of America, a new league that competed with the established National Basketball League (the two leagues merged after the 1948-49 season to form today’s National Basketball Association). With his former Seton Hall coach, Honey Russell, at the helm of the Boston Celtics club in the BAA, Connors signed to play with the Celtics for the inaugural 1946-47 season. Connors averaged 4.6 points per game in 49 games for the Celtics that season. He was no major offensive threat, as he sank less than one in four field-goal attempts (94-for-380) and less than half of his free throws (39-for-84). Connors later explained his primary role with the Celtics that season, which fortuitously led to the beginning of an acting career:

I’m positive my greatest value to the Celtics was as an after-dinner speaker. It seems to me I did more public speaking for the team than playing that first season. They sent me all over New England on speaking engagements. I’d pick up $25 or $50 an appearance, whatever the traffic would bear. When I wasn’t apologizing [for the few wins the team had], I was doing things like “Casey at the Bat” and “Face on the Bar Room Floor.” I did “Casey” at the Boston Baseball Writers Dinner that first winter, and Ted Williams was there too after winning the 1946 American League MVP Award. Ted was very kind to me and laughed his head off at my rendition. Afterward, he said to me, “Kid, I don’t know what kind of basketball player you are, but you ought to give it up and be an actor.” So doing those after-dinner speeches was my raison d’etre.12

Where Connors did establish his renown with the Boston Celtics on the basketball court was in a pregame warm-up on November 5, 1946, when he became the first player in NBA history to shatter a glass backboard. Contrary to the legend that developed, Connors did not shatter the backboard while attempting to dunk the basketball. “During the warm-ups, I took a set shot, a harmless set shot, and crash, the glass backboard shattered,” Connors recalled. The newfangled backboard was missing a key part, a piece of rubber between the glass and the rim, which caused the glass to shatter when the shot caromed off the rim. Because the Celtics game was being played at the Boston Arena, not at the Boston Garden, where Gene Autry‘s rodeo was playing to a large crowd, the Celtics management had to scramble to locate a replacement in order to play the game. Publicist Howie McHugh was dispatched to the Boston Garden to get a replacement backboard. “Howie tells how the Garden’s backboards were stored behind the Brahma bull pens, and nobody was fool enough to challenge the bulls for them,” Connors recalled. “Howie found two drunken cowboys and slipped them a couple of bucks to go into the pen, dodge the bulls, and get a glass backboard out. If he hadn’t, we might still be waiting at the Arena.”13

Connors is considered one of an elite group of fewer than a dozen athletes that played in both major-league baseball and the NBA, which includes Danny Ainge, Gene Conley, Dave DeBusschere, and Dick Groat. However, defining professional basketball as only teams in the NBA, or its forerunner the BAA, excludes many baseball players that played pro basketball in other leagues. According to Ted Brock’s research in Total Basketball, another dozen major-league ballplayers logged minutes with NBL teams, including Lou Boudreau, George Crowe, Irv Noren, and Del Rice.14

Connors left the Celtics in late February 1947 to go to spring training with the Brooklyn Dodgers. For the 1947 baseball season, the Dodgers sent Connors to their farm club in Mobile, Alabama, in the Class-AA Southern Association. He compiled a .255 batting average, belted 15 home runs, and drove in 82 runs to help Mobile win the Southern Association playoffs. Connors continued his ascent up the Dodgers’ minor-league chain, where the first base situation at the parent club was in a state of flux. For the 1947 season, Jackie Robinson played first base, which was not his natural position, just to get his bat into the lineup. Eddie Stevens, a regular first baseman for the Dodgers during the 1946 season, was shipped out to Montreal, Brooklyn’s top farm team. Howie Schultz, who split time with Stevens at first base in 1946 (and was another dual baseball-basketball athlete), was sold to the Philadelphia Phillies. Stevens was sold to the Pittsburgh Pirates after the 1947 season, clearing the way for Connors to at least play for Montreal in 1948 if not make the Brooklyn squad.

Connors, now a shrewd negotiator, played hard-to-get with the Boston Celtics to sign for the 1947-48 BAA season by claiming he had a deal to be player-coach of a Birmingham team in the new Southern Basketball League. While the Celtics eventually caved in to his contract demands, Connors played only four games for the Celtics before the team put him on waivers in November 1947 to save money, when they had acquired another center, Ed Sadowski. Connors always claimed he left basketball to concentrate on baseball. “Well, baseball and basketball didn’t mix. Definitely not,” Connors said. “I had to leave the Celtics in late February for spring training and figured I was in great shape because I had been running on the boards all winter. But because of that I found my legs actually were much tougher to get into condition. I think my baseball legs were bothered very much by basketball.”15

For the 1948 baseball season, the Dodgers assigned Connors to their top farm club in Montreal, where he hit a solid .307 with 17 home runs and 88 RBIs. Montreal won the International League playoffs and also the Little World Series, defeating St. Paul of the American Association. Back in Brooklyn, first base was still a merry-go-round until Gil Hodges became the regular first baseman midway through the 1948 season. Connors had a distinct shot at getting the first base job with Brooklyn in 1949, since Hodges hit just .249 in 1948. Connors did two things following the 1948 season to increase the odds of his promotion to Brooklyn. First, the 27-year-old bachelor settled down by marrying Elizabeth Riddell. Second, he finally abandoned his winter job as pro basketball player and played winter-league baseball with the Almendares ball club of the Cuban League.

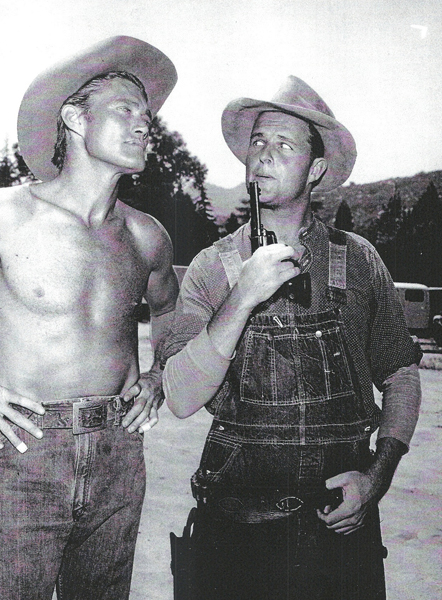

Connors had a commanding presence, at 6-foot-6 and 200 pounds, with steely blue eyes and a loud voice. Yet he had a playful nature inside, although he wasn’t a clown as many portrayed him. He had an inquisitive mind and a drive to succeed, a desire for achievement, whether in sports or the performing arts. Unfortunately, by 1949, Connors had acquired a bigger reputation as a comedian than as a ballplayer. He was the hit of the Dodgers Follies at the Vero Beach, Florida, spring training camp in March 1949.16 He even got his picture in The Sporting News reciting “Casey at the Bat.”17 One writer remarked that “Kevin (Chuck) Connors, latest entry in Brooklyn’s first base derby, is a ballplayer by occupation, a dramatic actor by instinct and a screwball by popular demand.”18 Connors even handed out calling cards that advertised his availability for “Recitations, After-Dinner Speaker, Home Recordings for any Occasion, Free Lance Writing.”19 In his book Tales from the Dodger Dugout, Carl Erskine tells a great story about how Connors entertained his Dodger teammates:

Chuck Connors used to do card tricks in the big lobby. One trick he did required the help of an accomplice. Chuck would send Toby Atwell down the road to a phone booth. Toby would sit in the booth with a flashlight and read a paperback Western and wait. In the lobby, Connors would entice a few bets that he could have someone draw a card from the deck and then call the Swami, who would identify the card. The ten of hearts is drawn; everybody in the room sees it. Connors then dials the number of the phone booth. Toby answers on the first ring and immediately begins to name the suits, “spades, hearts …” Connors interrupts when he hears “hearts” by saying “Hello, Swami.” Toby then rapidly names the cards, “king, queen, jack, ten …” Connors again interrupts on the “ten” and hands the phone to one of the bettors. In a monotone, Toby says, “This is the Swami. Your card is the ten of hearts,” and hangs up. Connors picks up the money.20

After making a good impression with his bat rather than his mouth with the Dodgers’ B squad during spring training in 1949, Connors got a shot at the Brooklyn first base job when he was elevated to the A squad for the April 7 exhibition game in Macon, Georgia. When Connors went 1-for-5 in that game, manager Burt Shotton penciled him into the lineup for the April 8 game in Atlanta. However, in a pregame fielding drill, Connors was hit in the mouth by a ball thrown by Bruce Edwards and was taken to a local hospital. He needed five stitches to close the wound, which swelled his upper lip to twice its size. That bad break cost Connors his major-league opportunity. After missing two exhibition games, he returned for the April 10 game, but went 0-for-3. His bad breaks continued when the next three games were rained out. In the April 14 game in Washington, D.C., Connors went 0-for-4. Worse, he had the crowd in stitches. “The fans laughed themselves silly over the performance of this bush league first baseman who seemed to be doing a takeoff on the old college try,” one writer wrote. “Later Chuck said he hadn’t tried to be funny, that he’d been hustling for keeps hoping to make an impression on Shotton.”21

Shotton wasn’t amused. For the three-game city series with the New York Yankees, he inserted Gil Hodges back into the lineup at first base. Hodges proceeded to win the first base job and was in the opening day lineup at Ebbets Field on April 19. However, the day before, the Dodgers announced that they had acquired Connors from their Montreal farm club to back up Hodges. “The Mighty Kevin recited his version of ‘Casey at the Bat’ last night with new gusto at the Knothole Club dinner,” the Brooklyn Eagle commented, “but he has no intention of playing Casey on the ball field.” The Eagle added, though, that “Connors doubtless will wear out the seat of his breeches squirming around on the bench.”22

Although Connors had made the Brooklyn team, Shotton kept him on the bench as Hodges played every day at first base. It wasn’t until May 1 that Connors got an opportunity to play. With the Dodgers losing 4–2 to the Phillies in the bottom of the ninth inning, Shotton had Connors pinch-hit for Carl Furillo with one out and a runner on first base. Connors, the potential tying run, faced Russ Meyer, who was pitching for the Phillies. “I knew I was going to get a hit and win the game. I mean I was squeezing the bat so hard that sawdust started running down the handle,” Connors recalled his big moment on the major-league stage. “On the next pitch Meyer threw me a belt-high fastball on the outside corner, I creamed it! I hit a one hop back to the mound and he turned it into a double play. I still see that pitch in my dreams. It’s as big as a zeppelin. If I had waited on it a little longer, I might still be playing.”23 After the game when Shotton was asked why he used Connors as a pinch-hitter, he responded, with a sigh, “To reduce the possibilities of a double play.”24

That was the extent of Connors’ career with the Brooklyn Dodgers: two pitches, one swing, and 0-for-1 in the box score. Connors actually got one more opportunity in a Brooklyn uniform. On May 2, in an exhibition game at West Point against the Army varsity baseball team, Connors played first base and went 2-for-5 at the plate. However, his performance in the exhibition game didn’t matter. He was soon ticketed back to Montreal for the remainder of the 1949 season, where he batted a hefty .319 with 20 home runs and 108 RBIs to lead Montreal to the International League pennant. Back in Brooklyn, Hodges had a 19-game hitting streak in May to solidify his hold on first base, as the Dodgers marched to the 1949 National League pennant.

He played one more year at Montreal in 1950, a solid but unspectacular season in which he compiled a .290 batting average but with just six homers and 68 RBIs. Connors knew he was going nowhere in the Brooklyn organization with Hodges now a fixture at first base, so he lobbied Dodgers president Branch Rickey to trade him. On October 10, 1950, Brooklyn announced that Connors had been traded to the Chicago Cubs along with Dee Fondy, another first baseman who had played with Fort Worth of the Texas League in 1950, for Hank Edwards and cash. When Chicago manager Frank Frisch installed Fondy as his first baseman during spring training in 1951, Connors was assigned to the Cubs top farm club, the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League. Not making the Chicago Cubs turned out to be the best thing that ever happened to Connors. “Now who goes to the games in LA? Producers, directors, writers, casting directors,” Connors recalled. “I became a kind of favorite of the show business people, unbeknownst to myself.”25

In Los Angeles, Connors thrived playing for the Angels. During the first half of the 1951 season, he compiled a .321 batting average in 98 games, with 22 home runs and 77 RBIs. By early July, Connors got the call to join the Chicago Cubs, switching places with Fondy, who was farmed out to the Angels. Connors was unspectacular in his half-season with the Cubs, though, hitting a weak .239 in 66 games with just two homers and 18 RBIs. He played fairly well for Frisch. But when Frisch was fired and replaced by Phil Cavaretta, a player-manager who was also a first baseman, Connors’s stock plummeted with the Cubs. Chicago finished in last place for the 1951 season and returned Connors to the Los Angeles Angels right after the season ended. Fondy became the Cubs’ regular first baseman for the next five years.

In September 1951, Connors received a phone call that changed his life. Bill Grady, the casting director for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, was a passionate fan of the Los Angeles Angels and asked Connors to test for a small role in the movie Pat and Mike, a film starring Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn. Connors got the five-minute part as the police captain and was paid $500 for just a few hours of work. Connors had found his post-baseball career. “I said right then, this is my racket,” Connors remembered. “Playing with Tracy and Hepburn, I was in the big leagues much faster than I arrived there in baseball.”26

Connors felt so strongly about his potential as an actor that in November 1951 he filed for an exemption to the major-league draft. “I’m more than satisfied to stay put in Los Angeles,” Connors said at the time. “The Coast League is one of the best leagues in baseball and the living and playing conditions are superior.”27 While this was a legitimate move for Connors to secure his future, it all but sealed his fate as a minor-league baseball player who would never return to the major leagues.

He played the 1952 season with the Los Angeles Angels, where he is best remembered for his showboating than his playing ability. For example, after hitting one home run, he slid into second base, cart wheeled to third base, then crawled to home plate. These antics added to his “screwball” reputation, where at various times in his minor-league career he threw raw hamburger to rowdy fans at a road game and taunted umpires with Shakespearean quotes. Connors had his mind on his future in acting: “When you’re playing professional sports, you’re in show business, too. You’re out there to please the crowd and a little showmanship doesn’t hurt.”28

After the 1952 baseball season concluded, Connors had roles in several more movies, including Trouble Along the Way and South Sea Woman. “I made $12,000 that offseason,” Connors avidly remembered about being a budding movie actor and his baseball salary being less than half that amount, “so I never reported to the Chicago Cubs for 1953.”29 In February 1953, Connors retired from baseball to focus on acting, which he felt was the “proper step” for his family in light of his belief that his baseball career had “reached the twilight stage.”30

While he had a reputation as a “zany” ballplayer, Connors was no buffoon as an actor. He asked questions and picked people’s brains to learn the show business. He took horseback riding lessons and learned to shoot a gun, to do his own stunts without need for a stuntman. He became renowned as a sharp businessman in the entertainment industry. “The day I left baseball, I became smart,” Connors said. “When I was in baseball, I played for the love of the game. I’d sign any contract they gave me. But then I stopped playing and began doing interviews with the players at the ball park. I began to see the light.”31 Of course, Connors had observed one of the masters of baseball negotiation, Branch Rickey. Connors was famous for remarking: “It was easy to figure out Mr. Rickey’s thinking about contracts. He had players and money—and just didn’t like to see the two of them mix.”32

His work blending external toughness with internal soft-heartedness in the movie Old Yeller led to his landing the role of Lucas McCain in the television series The Rifleman. The TV series ran for five years, from 1958 to 1963, and was very lucrative for Connors, who negotiated to receive a share of the show’s profits. McCain was a single father who lived on a ranch in North Fork, New Mexico, in the late 1870s. He raised his son Mark (played by Johnny Crawford) with moral lessons, not brute force, while protecting the area from the dangers of the Wild West with his Winchester rifle. The tender relationship between father and son in a violent world was the successful formula of The Rifleman.

“Lucas was a righteous character, despite the violence,” Connors explained. “We had the benefit of the father-son relationship, so I could have a little scene at the end of the show where I would explain to Mark, essentially, that sometimes violence is necessary, but it isn’t good.” When Mark would often say that Lucas had “won,” Connors would disabuse him of that attitude. “Wait a minute, son,” he would say. “You never win when you kill someone. It demeans you. It takes something away. People have got to learn to do away with violence and guns, and to love each other.”33 Connors had great admiration for that role: “I have a lot of pride in The Rifleman, because it was a great part, to play a good father, a strong man who believes in right and wrong.”34

Westerns were hot in television in the late 1950s. In March 1959, eight of the top ten TV shows were westerns, including The Rifleman ranked at number six. Connors was associated with a group of elite star actors such as James Arness (Gunsmoke), Hugh O’Brian (Wyatt Earp), James Garner (Maverick), and Richard Boone (Have Gun, Will Travel). Baseball skills came in handy to get the part as Lucas McCain, as Time magazine noted: “When he walked in to try out for Rifleman, the director suddenly pitched a rifle at him. Chuck fielded it neatly, got the job.”35

Ironically, as Connors became a star actor in Los Angeles during the late 1950s, the Dodgers relocated from Brooklyn to Los Angeles. Connors was often seen as a spectator at Dodger Stadium during the 1960s, talking to the likes of Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale. Connors was even an intermediary in their contract talks following the 1965 baseball season, a negotiation that author Jeff Katz called a “significant convergence of baseball and show business” since the two pitchers staged a holdout using a movie contract as leverage.36 Connors convinced Koufax and Drysdale to end their movie dreams and Dodgers management to offer each pitcher a contract worth more than $100,000 a season, then the benchmark salary for baseball’s most exceptional ballplayers.

During the 1950s, Connors and his wife Elizabeth raised their four sons Michael, Jeffrey, Stephen, and Kevin in a house in Woodland Hills, California. He later moved to a ranch in Tehachapi, California, about two and a half hours north of Los Angeles. Following his divorce from Elizabeth, Connors married Kamala Devi in 1963, whom he met on the set of the movie Geronimo, where Connors portrayed the famous Apache warrior. After they later divorced, Connors married Faith Quabius in 1977, but this third marriage lasted just a few years. When asked about the possibility of marrying a fourth time, Connors often evoked an age-old baseball quip, “No, three strikes and you’re out.”37

The Rifleman lasted five seasons, but by the end of the 1962–63 season the TV western had run its course as popular shows among viewers. After starring in three more short-lived TV series (Arrest and Trial, Branded, and Cowboy in Africa), Connors returned to movies in the late 1960s with roles in spaghetti westerns, a genre made famous by Clint Eastwood with action-packed western thrillers. Connors appeared in several spaghetti westerns, including The Proud and Damned and Kill Them All and Come Back Alone.

After he turned age 50 in 1971, Connors was rarely cast as a leading man, so he gravitated to villain roles that he had successfully played back in the 1950s. “Chuck would be a tremendous villain the rest of his career,” biographer Fury wrote, “because a man who was six and a half feet tall and capable of sheer menace in his eyes and demeanor, was truly a formidable and fearsome sight.”38 Christopher Sharrett, the author of the book The Rifleman, wrote: “Connors intended to parlay his threatening physique and face—with its ever-lengthening, lantern jaw—into recognition as the ‘new Boris Karloff,’ a status that never truly materialized.”39 Connors did attain modest acclaim as a screen villain in The Mad Bomber, Soylent Green, and Tourist Trap.

Connors was active in Republican politics in the 1960s and 1970s. He was a strong supporter of fellow Californian Richard Nixon, who was elected President in 1968, and fellow-actor Ronald Reagan, who was elected governor of California in 1966 and later was elected President in 1980. Connors had a celebrated meeting with Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev in 1973, after meeting him at a party at Nixon’s Western White House in San Clemente, California. “Spotting Mr. Connors in a denim shirt at the helicopter pad, Mr. Brezhnev rushed over and threw his arms around the tall rugged star, who hugged back and lifted the laughing Communist party leader off his feet,” the New York Times reported.40 The Connors/Brezhnev bear hug was captured by photographers and ran in many newspapers across the nation.

In 1977 Connors played slave-owner Tom Moore in Roots, a television mini-series that helped to raise the consciousness of America about the impact of slavery and racism. This villain role was the most challenging of his career, because the despicable Moore was so evil and racist. As biographer Fury wrote: “Connors was so convincing in his portrayal that he received hate mail for his fictional acts in the story, including Moore’s rape of Kizzy, the young black woman portrayed by Leslie Uggams.”41 Following his critically acclaimed performance in Roots, Connors continued acting for another 15 years, with his most prominent films being Airplane II and Salmonberries.

In July 1984, he received a star on Hollywood Boulevard’s celebrated Walk of Fame. Following the ceremony, the Los Angeles Dodgers hosted a party at Dodger Stadium to honor Connors, which Connors felt “was a bigger thrill than getting the star,” given that he had just one lone at-bat during his brief baseball career with the Brooklyn Dodgers 35 years earlier.42

Connors died in Los Angeles, California, on November 10, 1992. He is buried in San Fernando Mission Cemetery in Mission Hills, California, where his gravestone is adorned by a photo of him as The Rifleman along with the logos of the Dodgers and Cubs baseball teams and the Celtics basketball team.

Despite his fame as an actor, Connors remembered his humble Brooklyn upbringing and remained grounded as a person. “I couldn’t have all this as a ball player,” he mused in a 1966 interview as he gazed at the view of the San Fernando Valley from his home. “But maybe baseball is a purer, healthier way for a guy to make a living.”43 He also maintained his sense of humor. While he always contended that he’d rather have been Gil Hodges than The Rifleman, Connors kept his feelings about that light-hearted. In the late 1950s when an interviewer said to him that “but for Gil Hodges, you might be playing for the Dodgers,” Connors interrupted him by joking, “Shhhh! He’d be the Rifleman!”44

An updated version of this biography appeared in “From Spring Training to Screen Test: Baseball Players Turned Actors“ (SABR, 2018), edited by Rob Edelman and Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 “Chuck Connors Swaps Glove for Greasepaint, Acting Career,” Los Angeles Times, February 13, 1953: C1.

2 Roscoe McGowen, “Connors, Disappointed Dodger, Proves He Can Play—In Films,” The Sporting News, December 15, 1954: 22.

3 Cynthia Wilbur, “Chuck Connors,” For the Love of the Game: Baseball Memories from the Men Who Were There (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1992), 48.

4 John Ross, “Kevin Connors Flock Farmhand,” Brooklyn Eagle, June 18, 1940: 14.

5 David Fury, “Chuck Connors: The Man Behind the Rifle (Minneapolis: Artist’s Press, 1997), 36.

6 “Kevin Connors, College Star, Joins Fraser Club,” Lynn Evening Item, June 6, 1942.

7 Fury, Chuck Connors, 20.

8 George Sullivan, “Kevin (Chuck) Connors,” The Picture History of the Boston Celtics (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1982), 154–155.

9 “Lions, Bushwicks, Gamble Win Skeins in Game Tonight,” Brooklyn Eagle, July 25, 1945: 15.

10 Harold Burr, “Revival of Vaudeville in Chuck Connors’ Hands,” Brooklyn Eagle, March 27, 1949: 31.

11 Mordaunt Hall, “Wallace Beery as Chuck Connors and George Raft as Steve Brodie in a New Film, ‘The Bowery,’” New York Times, October 5, 1933: 24.

12 Sullivan, History of the Boston Celtics, 152–153.

13 Sullivan, History of the Boston Celtics, 153.

14 Ted Brock, “Multi-Sport Stars: Men for Two (or Three) Seasons,” Total Basketball: The Ultimate Basketball Encyclopedia (Toronto: Sport Media Publishing, 2003), 339.

15 Sullivan, History of the Boston Celtics, 154.

16 “Dodgers Move from Diamond to Stage in Vero Beach Verities,” The Sporting News, March 30, 1949: 22.

17 Tom Meany, “Connors Wins Laughs … Now Aims for Cheers,” The Sporting News, May 4, 1949: 5.

18 United Press, “Bums’ Rookie Connors Is Actor, Orator,” Hartford Courant, April 12, 1949: 16.

19 Bill Roeder, “Mr. Connors a Funny Man—By His Own Admission,” The Sporting News, October 25, 1950: 2.

20 Carl Erskine, Tales from the Dodger Dugout (New York: Sports Publishing, 2003), 209.

21 Roeder, “Mr. Connors a Funny Man.”

22 Harold Burr, “Dodgers Take on Connors for First Base Insurance,” Brooklyn Eagle, April 19, 1949: 17.

23 Fury, Chuck Connors, 48.

24 Tommy Holmes, “Dodgers, Below .500 Mark, Off to Disappointing Start in Race,” Brooklyn Eagle, May 2, 1949: 13.

25 Wilbur, For the Love of the Game, 51.

26 Bob Hunter, “Connors Chucked Bat for TV Riches,” The Sporting News, October 8, 1966: 32.

27 Associated Press, “Connors, Angels’ First Baseman, First Player to Oppose Draft,” New York Times, November 19, 1951: 41.

28 Sullivan, History of the Boston Celtics, 154.

29 Lynn Parrott, “The Chuck Connors Story—Ham to Star,” The Sporting News, January 9, 1959: 3.

30 “Chuck Connors Swaps Glove for Greasepaint, Acting Career.”

31 Murray Schumach, “Rifleman, Lawman,” New York Times, September 15, 1963: 143.

32 Joe Garagiola, Baseball Is a Funny Game (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1960), 148.

33 Fury, Chuck Connors, 136.

34 Fury, Chuck Connors, 294.

35 “The Six-Gun Galahad,” Time, March 30, 1959: 60.

36 Jeff Katz, “Everybody’s a Star: The Dodgers Go Hollywood,” The National Pastime, 2011: 75.

37 Fury, Chuck Connors, 311.

38 Fury, Chuck Connors, 206.

39 Christopher Sharrett, The Rifleman (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2005), 99.

40 John Herbers, “Brezhnev Leaves West on a Note of Informality,” New York Times, June 25, 1973: 1A.

41 Fury, Chuck Connors, 231.

42 Fury, Chuck Connors, 253.

43 Hunter, “Connors Chucked Bat for TV Riches.”

44 Tony Salin, “Now Batting for Furillo, the Rifleman,” Baseball’s Forgotten Heroes: One Fan’s Search for the Game’s Most Interesting Overlooked Players (Chicago: Masters Press, 1999), 16.

Full Name

Kevin Joseph Aloysius Connors

Born

April 10, 1921 at Brooklyn, NY (USA)

Died

November 10, 1992 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.