Del Ennis

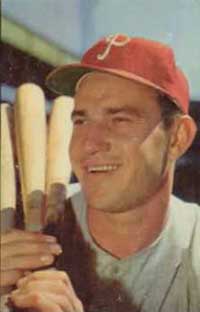

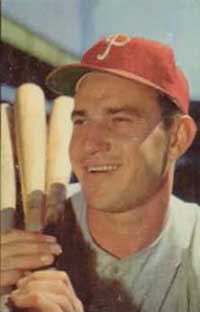

Right after the Shibe Park public address system announced, “Now batting for the Philadelphia Phillies, number 14, Del Ennis, left field,” either Gene Kelly or later Byrum Saam — both of whom did radio play-by-play for the Phillies — would say, “It’s Ding Dong Del” or “Here comes Ennis the Menace.” The radio listener could picture Del Ennis with a hand at each end of the bat, raising the bat over his head to stretch or loosen his back and shoulder muscles. Ennis would then stroke two practice swings and step into the batter’s box. There was nothing unusual about his stance. He was square to the plate, the bat was still; as the pitcher delivered the ball he would step toward the pitcher and if he liked the pitch, he swung, using shoulders, arms, and wrists that could belong to a blacksmith. And Ennis was a menace. Delmer Ennis, born in Philadelphia on June 8, 1925, menaced National League pitchers for 11 years as a member of the Philadelphia Phillies. Signed by the Phillies in 1943, he was a hometown product and the original Whiz Kid.

Right after the Shibe Park public address system announced, “Now batting for the Philadelphia Phillies, number 14, Del Ennis, left field,” either Gene Kelly or later Byrum Saam — both of whom did radio play-by-play for the Phillies — would say, “It’s Ding Dong Del” or “Here comes Ennis the Menace.” The radio listener could picture Del Ennis with a hand at each end of the bat, raising the bat over his head to stretch or loosen his back and shoulder muscles. Ennis would then stroke two practice swings and step into the batter’s box. There was nothing unusual about his stance. He was square to the plate, the bat was still; as the pitcher delivered the ball he would step toward the pitcher and if he liked the pitch, he swung, using shoulders, arms, and wrists that could belong to a blacksmith. And Ennis was a menace. Delmer Ennis, born in Philadelphia on June 8, 1925, menaced National League pitchers for 11 years as a member of the Philadelphia Phillies. Signed by the Phillies in 1943, he was a hometown product and the original Whiz Kid.

The Whiz Kids was the name given that group of young Phillies players who in 1950 won the team’s first National League pennant in 35 years. Twenty-five-year-old Del Ennis was the power behind the team. The “Kids” included, along with Ennis, Robin Roberts, Curt Simmons, Willie “Puddin’ Head” Jones, Granny Hamner, Bubba Church, Richie Ashburn, Stan Lopata, Ralph “Putsy” Caballero, Bob Miller, and Stan Hollmig, all of whom were younger than 25. Ennis had a huge July, which carried the Phillies into first place. He drove in 38 runs during that month.

In 1950 Ennis led the National League with 126 runs batted in; he was fourth in batting (.311), and fifth in home runs (31). He finished fourth in the MVP voting behind teammate Jim Konstanty, Stan Musial of the St. Louis Cardinals, and Eddie Stanky of the New York Giants. It was a memorable and talented team. Roberts and Ashburn were later voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame; first baseman Eddie Waitkus recovered from a 1949 gunshot wound inflicted by a “Baseball Annie” to become the story behind Bernard Malamud’s The Natural; and Dick Sisler (Hall of Famer George Sisler’s son) hit the clinching home run that defeated the Brooklyn Dodgers on the last day of the 1950 season. (George Sisler was scouting for the Dodgers at the time.)

In the spring of 1942 Phillies scout Jocko Collins took a 15-cent trolley ride from Shibe Park to Olney High School; he was anxious to see how a young pitcher named Dick McTough could handle a husky outfielder who played for Olney. That day, Ennis hit three home runs — two shots went onto the tennis court — and a bases-loaded double. Collins immediately lost interest in the pitcher and switched his attention to Ennis, who in high school played outfield, first base, and catcher. Del had also won all-state honors as a fullback for the Olney football team. The young Ennis resisted the scout, telling him he was not good enough for professional baseball. Collins hounded Ennis until Del’s father, George, the manager of the straw-hat division of Stetson Hats, sent back a signed contract.

The Phillies assigned Del to their Class-B Trenton team in 1943 and the youngster hit .346 with 18 home runs and 93 runs batted in. Soon after the baseball season ended, the 18-year-old Ennis enlisted in the US Navy. He was sent to the South Pacific, stationed with the rank of warrant officer on Guam. Ennis did not like Guam but he did get to meet and play some baseball with the likes of major leaguers Schoolboy Rowe, Johnny Vander Meer, and Billy Herman. Del developed a reputation and rumors got back to the major leagues about a kid on Guam who was hitting vicious line drives. Phils general manager Herb Pennock received — and refused — trade offers for his “navy kid.”

Ennis was discharged in April 1946 and the Phillies planned o give him another season of experience in the minors, but as a war veteran he was allowed to stay with the parent club, so manager Ben Chapman inserted him in left field during their first trip west. During that trip, Ennis hit two home runs at Wrigley Field, the first off Chicago Cubs ace Claude Passeau. He was in the lineup to stay. Ennis was named to the 1946 All-Star team and finished the season with a .313 batting average, 17 home runs, and 73 runs batted in. He was named The Sporting News Rookie of the Year. He finished eighth on the National League Most Valuable Player ballot.

Ennis suffered the “sophomore jinx” in 1947. His batting average (.275) and home run (12) totals were down, but after that, he became one of the top run producers in baseball, beginning with a 30-homer, 95-RBI season in 1948. From that point on his numbers were consistent with or even better than those of Mickey Mantle, Ted Williams, Willie Mays, Duke Snider, Gil Hodges, and Stan Musial. For the 10-year span from 1948 through 1957, Ennis batted in 1,075 runs — second only to Musial (1,120) over that period — while maintaining a batting average above .280 and belting, on average, 25 home runs per season.

Much has been said of Ennis’s fielding and some of it was not kind. However, he was capable of overcoming his mistakes, sometimes in spectacular fashion. According to Robin Roberts, once in the 1950 season, Ennis overran a shot to right field by Jackie Robinson and though off-stride, reached out and caught the ball barehanded. Robinson ran into right field, yelling at Ennis all the way, “How did you catch that ball?” Richie Ashburn observed, “Ennis reached up and caught the ball barehanded on the dead run, like picking an apple off a tree. He never cracked a smile, just like it was a routine play.”1 In 1952, at the Polo Grounds, the Giants’ Willie Mays slugged a ball to deep right-center field, near the 455-foot sign; Ennis was off at the crack of the bat. For Mays this could have been an inside-the-park home run. As Ennis was about to reach for the ball, he tripped over the right-center bullpen mound and as he was falling, reached out and caught the ball, again barehanded.

After the triumph of 1950, Ennis had a down year in 1951. The Philadelphia fans began to jeer and boo, and Ennis, the only Philadelphia native on the team, was their target. It didn’t help that the Phillies team never matched the promise the Whiz Kids showed in 1950. They were always finishing behind the Brooklyn Dodgers and their “Boys of Summer” or Durocher’s Giants or Musial’s Cardinals. In the 1950s New York baseball was in full bloom with the Yankees, Dodgers, and Giants consistently appearing in the World Series; there was no room for the aging Whiz Kids.

Ennis did suffer through a bad season in 1951. His batting average plummeted more than 40 points to .267, home runs fell off to 15, and his runs batted in amounted to only 73 after a league-leading 126 during the pennant-winning year. Ennis bounced from that 1951 slump with four straight seasons of 20-plus homers and 100-plus RBIs, and his 364 RBIs from 1953 through 1955 ranked second in the majors behind Snider’s 392. But he remained a target of the fans.

Thirty years or more later, Mike Schmidt received — and in the 2000s Pat Burrell also received — that same booing, but it never matched what Del Ennis endured from 1951 until he was traded to the Cardinals in 1956. Robin Roberts reported in his book The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant a comment by one of the Phillies’ young pitchers, Steve Ridzik:

“I had come to a ballgame against the Dodgers in Shibe Park. It was the seventh inning and we were ahead by three runs, but the bases were loaded with two outs. A fly ball goes out to Del and, with two outs, everybody is running. Damn if the ball doesn’t hit him on the heel of the glove and he drops it. All three runs score and we have a tie ballgame. We had a packed house and the fans start to boo him unmercifully. It was terrible.

“The next inning when he went out to left field they booed and booed and booed. They booed him when he ran off the field at the end of the inning. Unmerciful. I looked over at him sitting in the dugout and he’s got his hands clenched and he’s just white. He’s just livid. Here he is a hometown guy and everything. … He came to bat in the last of the eighth inning with the score still tied and two outs. The fans just booed and booed and all our guys on the bench are just hotter than a pistol. We were ready to fight the thirty-some thousand. He didn’t deserve that. So Del hits one on top of the roof and as he’s rounding the bases the crowd goes crazy. They cheered and cheered and cheered. They were standing and wouldn’t sit down. They wanted him to come out of the dugout. But he wouldn’t move. He just sat there as white as a ghost, mad as hell. When he went out in the ninth inning the fans stood up and applauded again. I had to step back off the rubber a couple of times because they wouldn’t sit down.

“That was one of the greatest thrills of my career, watching something like that happen to somebody else. It was beautiful.”2

Another time, in 1955, Ennis took his son to a game on the son’s birthday and the Phillies beat the Cardinals, 7-2. Ennis hit home runs in the first, sixth, and seventh innings and drove in all seven runs. He popped out on his other at-bat in the third inning and the fans “liked to boo me out of the park.”3 Several other times he answered the boo-birds with game-winning hits, but much of the booing over a five-year period was harsh. Ennis rationalized that he was from North Philly, and the booing was led by fans from South Philly. Ennis was traded to the Cardinals for Rip Repulski and Bobby Morgan after the 1956 season. When he returned to Philadelphia for the first time, he received a standing ovation that lasted long enough to indicate to Ennis that he had been appreciated.

In 1957 with the Cardinals, Ennis batted .286, with 24 home runs and 105 runs batted in while leaving a void in the middle of the Phillies lineup that wasn’t filled until Mike Schmidt arrived in Philadelphia. But the 1957 campaign was the last good season of Ennis’s career. In 1958 he hit only three home runs in 329 at-bats while dealing with a family crisis; The Sporting News reported that his wife had suffered a nervous breakdown during the season. That October Ennis was again traded, this time to the Cincinnati Reds.

Unfortunately for Ennis, the Reds’ new manager in 1959 was Mayo Smith, who Ennis felt had been instrumental in trading him away when Smith managed the Phillies from 1955 through 1957. Ennis said about the 1959 Reds in an interview in The Major Leaguer, “We had a good ballclub. We felt we could win. But, here again Mayo Smith had come over to manage the Reds then. I probably had my best spring ever that year too. I hit something like 12 home runs and had about 30 RBIs, but the manager initiated a platoon system in right field with Jerry Lynch.”4 Once the season started, Ennis got only 12 at-bats before being traded to the Chicago White Sox on May 1.

At the age of 34, Ennis finished his 14-season baseball career after playing in 26 games for the White Sox during their 1959 pennant-winning year. He batted .219, had 2 home runs, 6 doubles, and 7 runs batted in; the White Sox released Ennis on June 20. Ennis, however, was anxious to get back to Philadelphia, his family, and his bowling-alley business. He never really wanted to play for any team but the Phillies.

While with the Cardinals, Ennis roomed with Stan Musial, and “Stan the Man” advised him to get into the bowling-alley business. Del Ennis Lanes, a bowling alley owned and operated by Ennis and the Phillies’ longtime traveling secretary, John R. Wise, was opened in 1958. Both retired from the bowling-alley business around 1993. Ennis also raised and raced greyhounds; the names of his dogs were those of former teammates from the 1950 Whiz Kids: Granny, Richie, Bubba, Puddin’ Head, and so on. Ennis, along with Robin Roberts, was also instrumental in starting “Dream Team” activities — those fantasy-camp activities where men from all walks of life would enjoy a week playing baseball with former major-league stars.

Del and his wife, Liz, raised six children, but only one demonstrated Dad’s athletic ability. David Ennis was an infielder for the University of Delaware and became a lawyer in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania.

Del Ennis died on February 8, 1996, in his home in Huntingdon Valley, Pennsylvania, of complications from diabetes. He was survived by his wife, six children, 13 grandchildren, and one great-grandchild.

An earlier version of this biography originally appeared in SABR’s “Go-Go To Glory: The 1959 Chicago White Sox” (ACTA, 2009), edited by Don Zminda.

Sources

Eck, Frank, Associated Press, Monitor-Index and Democrat (Mobley, Missouri), November 29, 1946, 8.

Ennis, Liz, Telephone interview, March 10, 2008.

Fitzpatrick, Frank, “Why did they boo Del Ennis?” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 29, 2003, D1.

Lawson, Earl, “Redlegs ‘Gambling’ on Ennis’ Return to Old Slugging Form,” The Sporting News, October 15, 1958.

McKee, Don, “Ennis dies at age 70; starred for the Phils,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 10, 1996, C3.

Orodenker, Richard, editor, The Phillies Reader (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996).

Roberts, Robin, My Life in Baseball (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2003).

Notes

1 Robin Roberts and C. Paul Rogers III, The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant (Philadelphia, Temple University Press, 1996), 241.

2 Roberts and Rogers, 239-240.

3 Roberts and Rogers, 240.

4 “The Del Ennis Interview: That Philly Feeling.” The Major Leaguer, “America’s Baseball Newsletter,” 1985, 1-2.

Full Name

Delmer Ennis

Born

June 8, 1925 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

Died

February 8, 1996 at Huntingdon Valley, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.