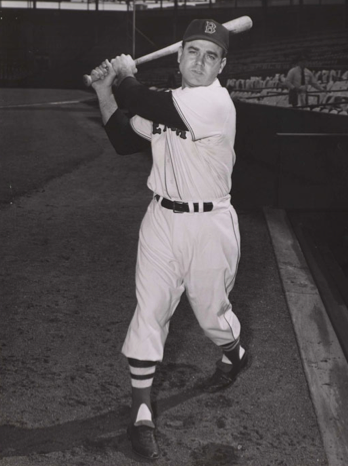

Al Zarilla

In what may be a unique event in the annals of baseball history, Al “Zeke” Zarilla had to buy a ticket to his major-league debut. He didn’t have to buy a plane ticket or a train ticket but the brand-new baseball recruit had to buy a game ticket to the game in which he was about to participate. On June 30, 1943, the St. Louis Browns played the first of a series of “Baseball for Victory” games at their home field, Sportman’s Park. Proceeds from the game went to benefit the National War funds; consequently, every spectator, player, umpire, and member of the press was required to buy a ticket. Zarilla paid his way into the game and smacked two hits (off Athletics right-hander Orie Arntzen) as the Browns went on to defeat the Mackmen, 3-1. Five years later, a grinning Zarilla said, “Best money I ever spent.”

In what may be a unique event in the annals of baseball history, Al “Zeke” Zarilla had to buy a ticket to his major-league debut. He didn’t have to buy a plane ticket or a train ticket but the brand-new baseball recruit had to buy a game ticket to the game in which he was about to participate. On June 30, 1943, the St. Louis Browns played the first of a series of “Baseball for Victory” games at their home field, Sportman’s Park. Proceeds from the game went to benefit the National War funds; consequently, every spectator, player, umpire, and member of the press was required to buy a ticket. Zarilla paid his way into the game and smacked two hits (off Athletics right-hander Orie Arntzen) as the Browns went on to defeat the Mackmen, 3-1. Five years later, a grinning Zarilla said, “Best money I ever spent.”

Allen Lee Zarilla was born on May 1, 1919, in Los Angeles to teenagers Carmen and Juanita Mercer Zarilla. Carmen, a first-generation Italian-American, was a truck driver and later a salesman in the family fruit business, where he worked with his father and brothers. Like many boys, young Allen learned to play baseball in the neighborhood sandlots. While still at Jefferson High School, the 17-year-old Zarilla caught the attention of Chicago Cubs scouts at a tryout camp in Los Angeles. He was one of 18 selected to play against strong semipro teams in the area. When Al broke his left ankle sliding into a base the first season, the Cubs’ interest waned. When Al asked for a $25-a-month raise, the interest evaporated.

Zarilla found another team in the winter league and was spotted by 15-year major-league veteran and Browns scout Jack Fournier, who signed him for a few hundred dollars. In the spring of 1938, Fournier sent Zarilla to San Antonio, Texas, where five Browns farm teams were training. None of the teams wanted him. He was then sent to Palestine, Texas, with the same result. Zarilla was about to be released when Fournier intervened. He called Elmer Kirchoff, player-manager of the Batesville (Arkansas) White Sox in the Class D Northeast Arkansas League. According to Donald Drees in Baseball Digest, Fournier told Kirchoff that Zarilla would hit .325 or Fournier would buy Elmer a new suit. Al did not disappoint. He hit .329 and led the league in runs, doubles, and total bases.

For the 1939 season, Zarilla was in Louisiana playing with the Lafayette (Louisiana) White Sox of the Class D Evangeline League. The 5-foot-11, 180-pound Zarilla hit .291 in 138 games for the second-place club. His 17 triples led the circuit. Al was back in Arkansas for the 1940 campaign but this time with the Helena Seaporters of the Class C Cotton States League. He paced the third-place Seaporters with a .349 batting average over 124 games. He had seven homers, 27 doubles, and, showing his speed, a league-leading 19 triples. Also in 1940, Zarilla married Southern California native Virginia Callahan. The pair had one child, Juanita, who was born just as the 1941 season was starting.

Zarilla parlayed his stellar 1940 season into a promotion the next year to the Class B Springfield (Illinois) Browns in the Three-I League. Zarilla spent only 25 games there (hitting .326) before the call-up came from the Class A1 Texas League San Antonio Missions. The 22-year-old outfielder hit a respectable .278 in 73 games for the Padres, who were managed by former Browns and Red Sox standout Marty McManus. Zarilla stayed with the Missions for the 1942 season as well and struggled the entire year. While he did manage to hit 23 doubles in 148 games, his average plummeted to .211. Looking back on that season six years later, Zarilla maintained that the Texas League was death on left-handed batters. He said the wind blew in from right field in all the parks and he didn’t learn to hit to left field until too late in the season. Possibly; but it doesn’t explain how he hit nearly .280 the year before. Whatever the reason, Zarilla would not be staying with the Texas League in 1943. In fact, no players did because the league, like many minor leagues, suspended operations for the duration of World War II. Luckily for Zarilla, his baseball “godfather,” Jack Fournier, was the manager of the Toledo Mud Hens, and the Double-A club had purchased Zarilla’s contract from San Antonio the previous October. Zarilla repaid the confidence shown in him by hitting a gaudy .373 in his first 57 games with Toledo. The parent club took notice; consequently, the depleted Browns called upon Al to make his major-league debut on the last day of June. Including the two hits in his debut, Zarilla hit safely in 13 of the first 18 games in which he came to bat before tailing off a bit at the end of July. Zarilla was with the Browns for the duration of the season and appeared in 70 games for the sixth-place team, including six games in center and 56 games in right field. He hit .254 (.364, 4-for-11 as a pinch-hitter) with two home runs and 17 RBIs. His first major-league home run came on August 29, in game two of a doubleheader, off Detroit Tigers starter Tommy Bridges. The solo shot wasn’t enough, though; the Browns lost to the Bengals 4-2.

When the ’43 season ended, Zarilla went home to Los Angeles, where he worked at a “war plant,” Western Pipe and Steel Company, as he had the previous offseason. Additionally, he played exhibition games in the California Winter League, an integrated professional league that dated back to 1910. The CWL was made up of Negro League teams, sometimes Negro League all-star teams, and major-league all-star teams. Zarilla played with teammate Vern Stephens, the Yankees’ Johnny Lindell, and the Senators’ Jerry Priddy among others on a team called Alan Lane’s All-Stars and also on his company team, the Western Pipe and Steel Boilermakers. Zarilla was having a good season at the plate until baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis put an end to the festivities. Landis ordered all the major-league players participating in the CWL to quit playing, invoking a rule against playing exhibition games more than 10 days after the World Series had been completed. He further ordered all players to submit an accounting of their earnings so he could levy fines – fines that would fully consume the money they had made playing the “illegal” games.

Zarilla’s next season, 1944, was a special season for the Browns. After spending most of their existence at or near the bottom of the American League (with the 1922 season a notable exception), the Brownies captured the pennant in ’44. They got out of the gate quickly, reeling off nine consecutive wins to start the season, and were at or near the top the entire campaign. A sizzling July and a torrid September run sealed the deal. Al Zarilla was a key contributor to the Browns’ success. Between July 23 and August 10, while the Browns were winning 14 of 16 games, Zarilla hit .466 (27-for-58) with three doubles, two triples, four homers, and 16 RBIs. The Browns’ lead over the second-place Red Sox ballooned to 6½ games, their biggest lead of the season. Zarilla hit safely in 14 of the 16 games, with nine multiple-hit games. Things were going so well for Zarilla he even got help from the umpires. On July 28, the Browns were facing the Athletics when Zarilla lined out in the bottom of the sixth. However, unbeknownst to Zarilla or the Philadelphia pitcher, Don Black, umpire Bill McGowan had called time prior to the pitch. Given new life, Zarilla promptly hit his fourth home run of the year to help the Brownies beat the A’s, 8-5.

Overall, Zeke, so named because he was from California and because he had bowlegs, reminiscent of a cowboy, had a fine first full season in the major leagues. The ever hustling, high-energy Zarilla was not a starter at the beginning of the season but earned the status as the season wore on. He hit .299 (86 for 288) with 13 doubles, 6 triples, 6 home runs, and 45 RBIs. The Browns succumbed to the Cardinals in the World Series, four games to two. Zarilla played in just four of the games, batting .100 (1-for-10) with one RBI. It was to be his only postseason appearance.

There would be no California Winter League for Al Zarilla after the 1944 season. In fact, his baseball career was put on hold when Uncle Sam called Zarilla into the Army. Zeke reported to Fort MacArthur in San Pedro, California, on October 25, 1944, and then was moved to Fort Warren, near Cheyenne, Wyoming. He served for the duration of the war and then reported to the Browns’ spring training camp in Anaheim, California, on February 20, 1946. With the war over, the star players returned to their major-league teams and the Browns were back to their usual position in the standings. Zarilla’s statistics declined in ’46; he hit .259 with 14 doubles, 9 triples, 4 homers, and 43 RBIs. Further, the right-hand-throwing Zarilla was now a starting outfielder for the seventh-place Browns, playing in 125 games overall and 107 in the outfield. The highlight of his season came on July 13, when he tied an American League record by hitting two triples in one inning as the Browns beat the Athletics, 11-4. Both the Browns and Zarilla had an even tougher season in 1947. The team slipped to eighth place, winning just 59 games. Zarilla, after starting off reasonably well (.272 through the first 29 games), had a terrible year at the plate, hitting an anemic .224 with 15 doubles, 6 triples, 3 homers, and 38 RBIs in 127 games. Clearly, this downward trend could not continue or Zarilla would find himself back in the minors. Luckily for Al, help was at hand.

Toward the end of the 1947 season, Browns coach Earle Combs, possessor of a .325 career batting average in 12 seasons with the Yankees, advised Zarilla to stop going for the long ball and to concentrate on hitting line drives for singles. “Just meet the ball,” Combs suggested, “and with your speed and baserunning ability, you’ll still get your share of doubles and triples.” After the ’47 season, Zeke played in the California Winter League (now approved by new Commissioner Happy Chandler) and caught up with old friend and Pirates slugger Ralph Kiner. Kiner told Zarilla to use a shorter, heavier bat because his current bat was “too quick” for him, causing him to pull more balls than he needed to. The final piece of advice came from new Browns manager Zack Taylor, who noticed during spring training in 1948 that Zarilla, who was learning to hit the ball to the opposite field, was “holding on to the bat too long.” Zeke put all these pieces together and had a breakout season in 1948; it was the year that established him as a major-league star, at least for a few years. He started quickly; 22 hits in his first 13 games, a .478 clip. On May 8, after a 4-for-4 day in which he figured in five runs as the Browns beat the Red Sox, 9-4, Zeke ran into Earle Combs, who was now coaching with Boston. Combs good-naturedly ribbed Zarilla about being “.450 in May and .250 in September.” The chiding seemed to spur Zarilla on. He went 3-for-3 the next day and then, after the normal tapering-off, he hit well over .300 the rest of the season, finishing at .329, fourth-best in the American League. He received over 930,000 votes from the fans in the All-Star balloting and was selected by Yankees manager Bucky Harris to play in the 1948 game. Zarilla replaced Joe DiMaggio in right field in the top of the fifth inning and went 0-for-2 at the plate. He had a late-season power surge as well. Zarilla hit his fourth home run of the season on August 1 and then hit eight more the rest of the way. Additionally, he had 39 doubles (a career high), three triples, and 74 RBIs. His 174 hits in 1948 were also a career high. Zarilla’s 1948 performance earned him a few votes among sportswriters for the MVP, the only time he was so honored.

After a “substantial” raise in pay and a bit part in the movie The Stratton Story during the offseason, Zeke was back with the Browns to start the 1949 season. He would not be there for long, however. On May 5, Zarilla, the last member of the 1944 pennant-winning Browns still with the team, was traded to the Boston Red Sox for outfielder/first baseman Stan Spence and at least $100,000 (some reports had the amount at $125,000 or $150,000). On the day of the trade, Red Sox manager Joe McCarthy said, “Zarilla is a hustling, lively type of ballplayer who can run, throw, and will be tickled to play in Boston.” Zarilla was thrilled to be going to a contender, later calling it “the best break I ever received in my life.” He may have been thrilled, but he was over-anxious as well, getting off to a slow start with his new club (he was hitting .250 for the Browns when traded). Then, on May 19 he hit his first homer with Boston. He scored the winning run in the bottom of the 12th inning against the Tigers on May 22. He hit a three-run homer against his old mates on May 25. On May 30, Zarilla hit the first grand slam of his career (off Athletics left-hander Bobby Shantz) and drove in six runs. In addition to winning the game, the grand slam off Shantz was personally important for Zarilla because it demonstrated to manager Joe McCarthy that Zarilla could hit lefties (he had been platooning in right field with Tommy O’Brien). After that hit, Zarilla was the regular right fielder for the 1949 Red Sox.

The 1949 season is one of the signature campaigns in the Red Sox-Yankees rivalry. Many column-inches and entire books have been devoted to that emotional rollercoaster of a season. Al Zarilla was in the middle of many of the key contests. The nadir for the Red Sox came on July 4. After losing the first game of a doubleheader to the Yankees, the Sox were in position to tie the second game with one out and the bases loaded in the top of the ninth. Zarilla came to the plate and a tremendous windstorm kicked up dust, obliterating the outfielders. The game was delayed for a few minutes and then Zarilla sent a Vic Raschi pitch on a line to right field for an apparent single. Johnny Pesky, on third base, should have scored easily but due to the dust didn’t get a good look at the ball. He went back to tag up. Yankees right fielder Cliff Mapes threw a strike to Yogi Berra to force Pesky. Zarilla’s poetic RBI single became a prosaic, if uncommon, right fielder-to-catcher fielder’s choice. The loss, the eighth consecutive for Boston, put the Olde Towne Team 12 back of their New York rivals. From this low point, however, the Red Sox went almost straight up. They won their next eight games and 61 of the next 81, a miraculous .753 winning percentage. On August 17, Zeke had a two-run double in the top of the tenth to beat the A’s, 5-1.

On September 2, Zarilla had a three-run inside-the-park home run to help the Sox defeat the A’s, 8-4. It was the first inside-the-park homer at Fenway Park since 1931. On September 24, Zarilla made a great play on the basepaths, scoring from second on an attempted first-to-catcher-to-first double play. He scored what proved to be the winning run in a 3-0 shutout of the Yankees, getting the Red Sox within one game of the league leaders. Zarilla made two spectacular catches against the Yankees in New York on September 26. In the second inning, he robbed Johnny Lindell of a three-run homer and then took away another potential home run in the ninth, this time frustrating Tommy Henrich. Since the Red Sox won the game, 7-6 and took over first place, it’s not an exaggeration to say Zarilla saved the day. After beating Washington on September 30, the Red Sox had a one-game lead with two to play. The last two games of the 1949 season have been well chronicled. The key hit in the last game, the deciding game, came off the bat of Yankees rookie second baseman Jerry Coleman. In the bottom of the eighth with the sacks full, Coleman lofted a looping fly (a “cheap hit” he would later call it) to shallow right. Zarilla, who was not deep, ran and dove but the ball fell a couple of inches from his glove and a couple of inches inside the foul line. With two outs, the runners were off at the crack of the bat and all three scored. Zarilla stayed in the game, but later was hospitalized to repair a blood vessel in his knee that had been ruptured on that play. Still, Zeke had a good season for the Sox. He hit .281 with 32 doubles, 9 homers, and 71 RBIs in 124 games with the Boston club. He was solid in right field as well with six assists and just four errors in 251 chances.

The Red Sox were an offensive juggernaut in 1950, scoring 1,027 runs in 154 games, and hitting.302 as a team. Six of the starting eight players hit over .300 with Bobby Doerr (.294) and Vern Stephens (.295) just missing. Zarilla was a big part of the attack. He hit .325 in his first full year with the club, with 32 doubles (seventh in the AL), 10 triples (fourth), 9 homers, and 74 knocked in over 130 games. On June 8, the Red Sox thumped the hapless Browns 29-4 before 5,105 fans at Fenway Park. Zarilla went 5-for-7 with four doubles and four runs scored, but, amazingly, no runs driven in. On Aug 28, the Red Sox were losing 12-1 in the fourth inning but came back to beat the Indians 15-14. Zeke’s eighth-inning homer proved to be the difference. Overall he was 2-for-4 with three RBIs. Unfortunately for the Red Sox, their pitching did not match their hitting and the Sox finished third, four games behind the Yankees. The need to shore up the pitching, however, meant a change of uniforms for Al Zarilla before the 1951 season. The Red Sox had been coveting Ray Scarborough, lately with the White Sox, who they thought could solidify their staff. The Yankees also coveted Scarborough and that, no doubt, played a part in the Sox’ acquisition. The Red Sox had Billy Goodman, winner of the 1950 American League batting crown, ready to play right field, which made Zarilla expendable. On December 10, 1950, the Red Sox traded Zarilla and pitchers Joe Dobson and Dick Littlefield to the Chicago White Sox for Scarborough and lefty Bill Wight.

White Sox general manager Frank Lane and manager Paul Richards wanted Zarilla to anchor their outfield. He was a big part of their plans for the 1951 season and they paid him accordingly. On January 30, 1951, Zarilla signed a contract calling for a $20,000 salary, making him the highest paid player on the team. Zarilla started quickly hitting a home run in each of the first two games of the season, and finished April with three homers and 12 RBIs. The White Sox were doing well through mid-May, keeping the league leaders in view; then, unexpectedly, the Pale Hose reeled off 14 consecutive wins (the first 11 were road wins), between May 15 and May 30 to take over first place. During the streak, Zarilla hit .300 (15-for-50) with five doubles, a homer, and 15 RBIs. By June 14, the White Sox had a 4½-game lead over the Yankees, but the Chicagoans could not hold on. They finished the season in fourth place, 17 games behind the league-leading Yankees. Zarilla batted .257 in 120 games with the White Sox. He had 21 doubles, 2 triples, 10 homers, and 60 RBIs. It was not a horrendous year, but it was a significant fall-off from his offensive production of the prior season.

The following season, Zarilla had a slow start (hitting only .232 in 39 games). On June 15, 1952, he and a teammate, shortstop Willy Miranda, were traded to the Browns for infielder Leo Thomas and outfielder Tom Wright. Zeke was to be back with his original team for only 48 games because on August 31, the Red Sox, who were trying to make a move on the Yankees, purchased his contract for the $10,000 waiver fee. Zarilla finished the season with the Red Sox. Overall, he had his worst year in the majors, hitting .225 with little power and just 24 RBIs in 104 games. After the season, Zarilla, who for years worked as a “grip” in the offseason at Columbia Studios, got his second chance to appear in a feature film when he landed a bit part in the Grover Cleveland Alexander bio-pic The Winning Team, starring Ronald Reagan and Doris Day. Zarilla, now 34, was relegated to the bench for 1953, his last season in the big leagues. He got into only 57 games (only 18 in the field) for the fourth-place Red Sox. Zarilla batted just .194 (13-for-67) with 4 RBIs. He played in his last major-league game on September 27, 1953, and was given his release the following January 6.

Like many players of his era, Zarilla went to the Pacific Coast League when he could not get a position in the majors. In 1954, Zeke signed to play the outfield with the Seattle Rainiers, who were managed by former major leaguer and California Winter League alumnus Jerry Priddy. The team included other former major leaguers such as Gene Bearden and Tommy Byrne. Zarilla managed to hit only .216 in 113 games. He played in the PCL in 1955 as well but only on a limited basis. He played a combined 42 games for the San Diego Padres and for the Hollywood Stars, hitting .200 (18-for-90). Clearly, the 36-year-old Zarilla was nearing the end of his playing days. The Chicago Cubs hired him to manage their Class C affiliate, the Magic Valley (Idaho) Cowboys in the Pioneer League for 1956. It must have been quite a change for Zarilla, who had been playing with grizzled veterans but now was managing teenagers and players in their early 20s. The Cowboys came in fourth in the eight-team circuit. Zarilla had 20 at-bats in 11 games, getting seven hits (.350).

After his playing days were over, Zarilla worked at scouting and coaching. On December 12, 1957, the Kansas City Athletics announced that they had signed him as their scout for Southern California (Zarilla was living in Bishop, California, at the time). In 1958, he was scouting in Tucson and spotted Diego Segui. On Zarilla’s recommendation, the Athletics signed Segui, who pitched 15 seasons in the big leagues. Zarilla remained a scout with the Athletics until September 1961, when he and five other A’s scouts quit, citing disagreements with the operating policies of new owner Charlie Finley.

Zarilla scouted for the Cincinnati Reds from 1962 through at least 1968. The Reds signed two of his finds, Casey Cox and Wayne Simpson, both of whom played major league baseball. Zarilla also scouted and recommended high-school player Chris Chambliss to the Reds; however the Reds failed to sign him in 1967 and then again in 1968 (Chambliss, of course, eventually went on to a successful 17-year major-league career). In October 1970, Zarilla became a full-time scout in California for the Washington Senators, managed by his former teammate Ted Williams. After the All-Star Game in 1971, Zarilla became a coach for the Senators, enabling him to accrue the 90 days of major-league service he needed to double his pension.

In 1972, Zarilla moved to Hawaii, where he was a part-time scout for the Major League Scouting Bureau and, by 1978, the first-base coach of the Hawaii Islanders of the Pacific Coast League. In later years, Zeke was often seen at Aloha Stadium and later Rainbow Stadium. He enjoyed baseball at every level. He especially enjoyed being around the younger, developing players with whom he could share his many years of experience and knowledge. On Aug 28, 1996, in Honolulu, Al Zarilla succumbed to cancer at the age of 77. He was survived by his wife, Virginia, and his daughter, Juanita.

Sources

Chicago Daily Tribune, 1943–1953.

Los Angeles Times. 1943–1953.

New York Times. 1943–1953.

Washington Post. 1943–1953.

Les Biederman, “Zarilla Says ‘It’s Great to Be With Winner,’” The Sporting News, April 19, 1950, 11.

Donald H. Drees, “Zealous Zeke Zarilla,” Baseball Digest, October 1948, 53-59.

Ferd Lewis, “Baseball Loses One of Its Own,” Honolulu Advertiser, September 4, 1996, C1.

William F. McNeil, The California Winter League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2002).

Steve O’Leary, “Zeke Zarilla, Southpaw Swinger, Proves Batting Poison to Opposing Portsiders, ” Sporting News. June 21, 1950, 13.

Cecilia Tan and Bill Nowlin, The 50 Greatest Red Sox Games (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley, 2006).

“Top Secret in Boston,” undated (circa 1951), unattributed article in Zarilla’s Hall of Fame clipping file.

Full Name

Allen Lee Zarilla

Born

May 1, 1919 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

Died

August 28, 1996 at Honolulu, HI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.