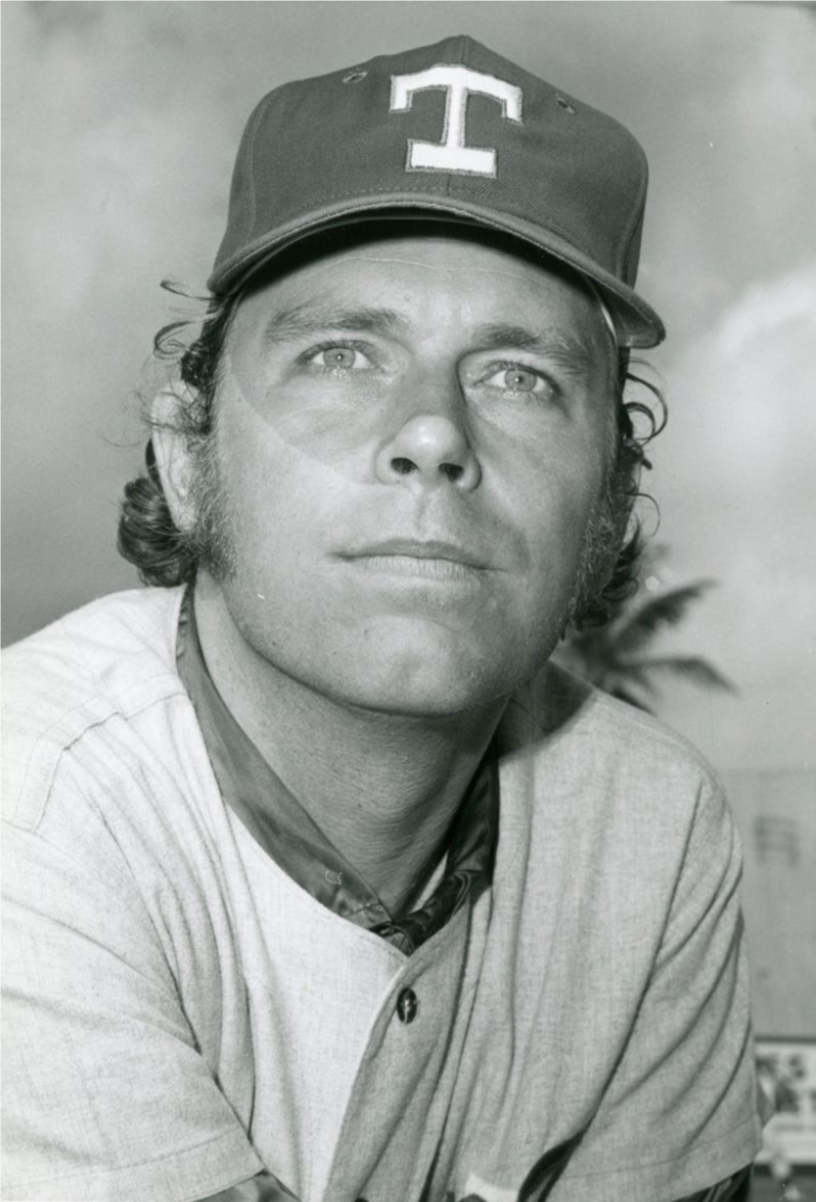

Casey Cox

“Career Performance” is a term that is quite often used, and for pitcher Casey Cox, his career performance came on July 7, 1969. Casey was pitching for Washington against the Cleveland Indians. The perennial second-division Senators were having a pretty good year and their victory that night put them within 3½ games of second place in the American League’s Eastern Division. Cox came into the game for Washington with one out in the top of the third inning. The bases were loaded, and Washington was trailing 2-1. Cox retired 20 all batters he faced as the Senators came from behind to win. (Lou Klimchock reached first in the eighth inning when center fielder Del Unser dropped his fly ball, but Unser gunned down Klimchock trying to advance to second base.)

“Career Performance” is a term that is quite often used, and for pitcher Casey Cox, his career performance came on July 7, 1969. Casey was pitching for Washington against the Cleveland Indians. The perennial second-division Senators were having a pretty good year and their victory that night put them within 3½ games of second place in the American League’s Eastern Division. Cox came into the game for Washington with one out in the top of the third inning. The bases were loaded, and Washington was trailing 2-1. Cox retired 20 all batters he faced as the Senators came from behind to win. (Lou Klimchock reached first in the eighth inning when center fielder Del Unser dropped his fly ball, but Unser gunned down Klimchock trying to advance to second base.)

Cox was not known for his hitting but in the fourth inning he laid down a perfect bunt to score catcher Jim French from third. The next day, Cox’s teammates presented him with a bright red batting glove.1

But it was Cox’s pitching that drew the real plaudits from his batterymate. “Casey has never been better,” French said. “That was the best sinker he has ever had. After pitching four innings in Boston Saturday night, he was just tired enough to have his sinker working to perfection.”2

The win was Cox’s sixth of the season and dropped his ERA to a stunning 1.88.

The 1969 Senators went on to win 86 games and finish in fourth place in the AL East. The wins were their most since they began as an expansion team in 1961, and the most of any Washington team since 1945. Toward the end of the season, manager Ted Williams called Cox one of his team’s two best pitchers (along with 14-game-winner Dick Bosman).3 Cox, in his fourth season with the Senators, had arrived, posting a 12-7 record with a 2.78 ERA. The Alexandria Club of Grandstand Managers concurred with Williams, presenting Cox with a silver service set at the end of the season.4

In 1972 Cox traveled with the Senators as they became the Texas Rangers. It was his 10th stop in a professional career that had begun in 1962.

Joseph Casey Cox entered the world on July 3, 1941, in Long Beach, California. His parents were Joseph Casey Cox and Esther Cox. (Casey was named for his grandfathers, and was called Casey from an early age to avoid being confused with his father.) Casey’s younger sister, Ann Louise, became a noted cell behavioral research scientist.

Cox’s father, an accountant, wasted no time in introducing his son to baseball and by the time young Casey was 8, they were determined that young Casey would become a major-league ballplayer, just like Casey’s hero, Bob Lemon. Casey starred in baseball and basketball at Woodrow Wilson High School (Class of 1959), went to Long Beach City College for two years, then to Los Angeles State College in 1961. He pitched one season at LA State, and impressed scouts when he struck out 17 Arizona Wildcats in one outing.5

Cox was signed in June 1962 by scout Al Zarilla of the Cincinnati Reds for a bonus of $9,000, with an additional $8,000 to come if Cox made it to the majors. Given a choice of three minor-league destinations, he chose Rocky Mount of the Class B Carolina League. In his first appearance, on June 17, he took a no-hitter into the sixth inning against Burlington, and allowed only one run and three hits in eight innings. But Rocky Mount lost, 3-0.6 In his second start, on June 24, he earned his first professional win, needing only 90 pitches for a 7-1 complete-game victory over Winston-Salem.7 But despite those two gems, first-year losses outnumbered wins: 4-8 with a 4.37 ERA. Cox went to the Florida Instructional League after the season. On November 26 he was claimed by the Cleveland Indians in the annual draft of first-year minor-league players.

Cox began the 1963 season with Charleston, West Virginia, in the Double-A Eastern League, going 0-2 before being sent to Burlington of the Carolina League on May 9. Three weeks later he was sold to the Senators to make room for Early Wynn, who signed with the Indians to try to hit the 300-win mark. The Senators assigned Cox to their Peninsula farm club, making it three Carolina League teams in less than 12 months. With Peninsula, he went 9-10 with an ERA of 3.37 in 31 games.

In 1964 Washington changed its Carolina League affiliation to Rocky Mount, and Cox was back where he started. He got off to a great start, and as late as June 21, his ERA was 1.59. In his first 64 appearances, he had an ERA of 2.48, third best in the league. He tailed off in his last five appearances, but was the workhorse of the bullpen. Pitching in a league-high 69 games (only three starts), his 185 innings were third best in the league and tops among relievers. He went 9-10 with a 3.16 ERA for a team that finished at 61-77.

Cox began the 1965 season in Hawaii in the Triple-A Pacific Coast League, but after nine appearances during which his ERA stood at 5.40, he was reassigned to York, Pennsylvania in the Double-A Eastern League. Appearing in 61 games, all but one in relief, he was able to put together a 9-2 record with a 2.03 ERA. Working with roving pitching instructor Sid Hudson,8 he was among the league leaders in ERA all season and posted a 9-2 record. Cox had hoped to be called up to the Senators at the end of the season, but went home disappointed.

“There was nothing else I ever wanted to do but get to the big leagues. Boy, this big-league life is it. It’s the only way to live.”9 And in 1966 he would get to the big leagues for the first time, at age 24 with a competitive zeal that was commented on during spring training by pitching coach Rube Walker: “He has a lot of determination for a rookie. He has a lot of spirit and we’re taking a long look at him.”10 Cox also impressed manager Gil Hodges with his coolness under fire. Hodges said, “Cox has shown real poise. … A couple of years ago, he was a dart-thrower. Now, he’s a pitcher.”11

Cox made his major-league debut on April 15, 1966. Recalling his debut close to 50 years later, he remembered that he was so nervous that “you couldn’t shove a pin up my ass with a jackhammer.” His first pitch went only 45 feet. He collected himself and went on to hurl two hitless innings in a Washington loss at Detroit. When he struck out the last batter he faced, Al Kaline, he had his first career strikeout. “I threw him a fastball and a slider for strikes. Then I tried to cut it too fine but missed and a low changeup made it 3-and-2. I got him with a low and away fastball.”12 Eight days later he picked up his first save, getting the last five outs, including a strikeout of Willie Horton for the final out, in a 5-3 Senators win over the Tigers. The Senators kept Cox busy. He pitched in 21 of his team’s first 41 games, and the team was enjoying the dizzying heights of the first division. By June 2 Cox had five saves and his ERA was 2.87. The team had risen to fifth place and was within seven games of the league lead. As the season wore on, the Senators faded. Cox wound up appearing in a team-leading 66 games, compiling a 4-5 record with seven saves and a 3.50 ERA.

Sometimes a ballplayer learns a lesson from adversity and on July 19, 1966, a circumstance arose that almost 50 years later, Cox was still able to remember. He had earlier told the story to Merrell Whittlesey in 1971. “We were playing the Twins and Harmon Killebrew beat me with a hit with two out in the ninth inning (it was actually the eighth inning). The next day Hodges casually asked me how much money I thought Killebrew made, and at the time it was about $75,000, or that was my guess. I forget who the next batter was – it wasn’t Tony Oliva – and he asked me how much I thought that fellow (Earl Battey) made, and I guessed $25,000. Gil told me that there must be some reason that Killebrew made $75,000 and the next hitter made $25,000, and to keep that in mind the next time I faced a big star with just an average hitter next up. I’ve never forgotten it, and you’d be surprised how much that has helped.”13

Cox spent part of the winter pitching for the Licey Tigers in the Dominican League. His stay was cut short after an altercation on November 15 between Cox and some disapproving fans. He reacted to their taunts by making an “offensive gesture”14 toward the stands. Cox was jailed, fined $50, and suspended for a week.15 The gesture had resulted in several fans advancing toward the field. One of the fans made it as far as the dugout, and the police spent the balance of the game protecting Cox. The next day he headed home.16 His season in the Caribbean was over.17

As the 1967 season approached, an optimistic Cox exclaimed, “There’s something in the air in this (spring-training) camp. It’s like a lot of young guys getting together and having pride.”18 But once the season started, Cox appeared in only six of his team’s first 23 games, pitching only eight innings with no decisions. He was sent to Honolulu at roster cutdown time in May. After pitching in 14 games in less than a month, Cox was summoned back to Washington on June 7 and was used regularly the rest of the season. In 54 games he had a 7-4 record and a 2.96 ERA. The Senators finished the season in a sixth-place tie, 15½ games out of first place.

In 1968 Jim Lemon replaced Gil Hodges as manager and inherited a strong bullpen. The six top relievers had chalked up 310 relief appearances in 1967, but Cox would not be a factor with the Senators in 1968. Toward the end of spring training, he was assigned to Buffalo of the International League, where he went 7-5. It was not a happy time for Cox, who was unable to escape the futility of being stuck in the minors hoping for a call-up that never came. After the minor-league season ended, Cox was recalled to Washington and got into four games with the Senators.

During the offseason, the Senators acquired a new owner, Bob Short. Cox was philosophical about the change: “I hope they have a place for me. I can see this man (Short) means business, and I’d like to be part of it.”19

Cox made the 1969 team out of spring training and had an early-season highlight on April 26 against Cleveland. He entered the game with one out in the first inning, relieving Barry Moore, who had walked four consecutive batters with one out. Cox induced Cleveland’s Max Alvis to hit a comebacker that Cox turned into a 1-2-3 double play. Cox remained in the game and scattered six hits over the remaining eight innings as the Senators won, 8-1. “They told me not to be a hero, just go as far as I could. After seven or eight innings, I still felt good,” he said.20 Manager Ted Williams kept telling Cox not to be a “hero,” and to tell him if he was tiring. Cox said, “I felt better in the last three innings, though, than in the middle three.”21 At bat he reached first base for the first time in his career, walking in the fourth inning. In the seventh inning he had his first career RBI when Jack Hamilton walked him with the bases loaded.

But Cox had yet to get his first major-league hit and took a fair amount of kidding. When he asked to borrow a bat from Hank Allen, the outfielder was a bit apprehensive. One of the players on the bench said, “Give it to him. He could use it for 100 years and never hurt it.”22

Manager Williams, a fair student of hitting, was more interested in Cox being a success on the mound. One particularly memorable experience was a game against the Twins on June 8. The Twins used seven pitchers and Cox was the last of the five pitchers used by the Senators. The game went into extra innings tied 5-5. Cox entered the game in the bottom of the 11th inning. Two hits and an intentional walk loaded the bases, bringing up Cox’s old nemesis Harmon Killebrew, who already had doubled and homered. The count went to 3-and-2. Walking Killebrew was not an option. Cox threw a low fastball that eluded the swinging bat of Killebrew. Del Unser’s two-run homer in the 12th inning gave the Senators a lead and Cox retired the Twins in bottom of the inning to secure his fourth win of the season.

“Fortunately, playing for Ted Williams has helped me to gain the confidence and concentration that a pitcher needs in a situation like that,” Cox said. “In other years, I might have beaten myself in a comparable situation. But I was thinking positive, to get the ball over. It was a big pitch. I’ll never forget it.” He noted the three keys to his success – Confidence, Concentration, and Control.23

There was a shortage of starting pitchers on the 1969 Senators and Williams on June 23 began using Cox as a spot starter. In his first start, Cox pitched 5⅓ innings of scoreless ball at Baltimore, and was in line for the win. However, the bullpen let him down and the Orioles came back to win, 5-3. On July 1 Cox threw his first career complete game, as Washington defeated Cleveland, 4-1. In 13 starts, Cox went 5-4. His record in relief was 7-3.

Between his long relief stints and occasional starting roles, Cox was getting to swing the bat more often, but his average remained at .000 (0-for-32) on July 17. On that day Cox started against the Tigers and singled off Earl Wilson in the third and fifth innings. The line drive to right in the third inning resulted in a standing ovation.24 But the Senators’ bats were cold, and Cox, who went into the game with a five-game winning streak, did not have his best stuff, surrendering a three-run homer to Willie Horton in the first inning. Cox was removed for a pinch-hitter in the seventh inning with the Senators trailing 3-1. Washington lost, 4-3, and Cox was charged with his second loss of the season, but he finally had his first major-league hits. He ended the season with five hits and a .106 batting average. He got only 10 more hits in the major leagues, and his career batting average was a dismal .099 (15-for-151).

Hitting aside, 1969 was a breakout season for Cox. He was 12-7 with a 2.78 ERA as the Senators went 86-76 under the stewardship of first-year manager Williams. The 1970 season couldn’t come soon enough, and Williams promised Cox a new set of golf clubs if he got 12 hits during 1970.25

Cox got even more chances at the plate in 1970, starting 30 games. In his first three starts he yielded 12 runs in 21 innings for a gaudy 4.29 ERA. However, he had some offensive help and came away with three wins. He recognized his good fortune, saying, “There are some pitchers who get runs scored for them, and none of those pitchers ever gives them back.”26

Cox stayed in the rotation for most of the season and went 8-12 with a 4.45 ERA, pitching a career high 192⅓ innings. His failure to replicate the success of 1969 was caused in part by his failure to keep the ball in the park. He gave up more homers (27) than anyone else on the Washington staff. From July 9 through August 31, Cox gave up at least one homer in each of 11 consecutive starts. His only complete game of the season, a 9-3 win over Cleveland on July 9, broke a string of 30 games in which Senators pitchers failed to complete what they started.27 Williams did not have to spring for the golf clubs; Cox had only seven hits during the season. The team lost its last 14 games of the season to finish in last place at 70-92.

After the season Cox ventured to La Guaira, Venezuela, to play winter ball and worked on his curveball, winning three of six decisions. After the disappointing 1970 season in Washington, he expected that 1971 would be different. “I believe that (in spring training) Ted (Williams) will be more critical, and I think that will help us.”28

By May 24 it was clear that a move to the bullpen was in order for Cox. In his first 11 appearances, 10 as a starter, he had gone 0-2 with a 4.50 ERA. After a poor performance on May 24, “I went to Ted and told him I could help the team more as a relief pitcher. He said that was fine and he would try me there. And the very next night, I got a win in relief.”29 He excelled in relief, and in 26 games from May 25 to August 3, he pitched 49 innings, and had an ERA of 1.47.

Williams said, “That’s where he should have been all along, but we needed a starter and he did a good job. … Now I’ll say flatly that he is the best right-handed relief pitcher in the league.”30

Cox’s poor performance as a starter in 1971 meant his overall numbers for the sixth-place Senators were not as good. He went 5-7 in 54 games with seven saves and an ERA of 3.98. He was back at home in the bullpen. In August he said, “I like what I’m doing. There is great satisfaction to saving a game as well as winning one. I have found a baseball home and I want to stay there, and hopefully with the Senators for at least five more years.”31

But as the season ended and September became October, it was clear that neither Cox nor any of his teammates would be with the Washington Senators beyond 1971, as owner Bob Short moved the club to the Dallas-Fort Worth area in October. The Washington Senators became the Texas Rangers. Cox relocated to the Dallas area shortly after the move was announced.

By the time the move to Texas was made, Cox was one of the longest-tenured players on the team, along with Dick Bosman and Frank Howard. He went 3-5 with the Rangers, sporting an ERA of 4.41 when, at the end of August, he was traded to the New York Yankees for pitcher Jim Roland. The Yankees, who had not won anything of note since the 1964 American League pennant, were a .500 ballclub in 1972. They finished at 79-76, good for fourth place in the AL East. The 30-year-old Cox pitched in five games down the stretch, going 0-1 with a 4.63 ERA and no saves.

Cox returned to the Yankees in 1973, but after an unsuccessful outing on Opening Day, he was released on April 17. He went back to the minors, pitching that season for the Wichita Aeros, the Cubs’ affiliate in the Triple-A American Association. He went 6-5 for the Aeros with a 5.05 ERA, and retired at the end of the season.

Cox has been inducted into several school Halls of Fame in the Long Beach area, and was inducted in the City of Long Beach Hall of Fame in 2007.

Cox has had multiple marriages and had one child, Carol Ann, during his first marriage. Carol Ann died at age 44 in 2008. After his playing days, he entered the world of insurance, starting out by selling life insurance. He joined a firm in Florida that paid life, medical, and dental claims for several large group clients. He eventually acquired ownership of the firm. In retirement, he has worked in various capacities for the local Republican Party near his home in Florida.

This article was published in “The Team That Couldn’t Hit: The 1972 Texas Rangers” (SABR, 2019), edited by Steve West and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also relied on:

Addie, Bob. “Cutdown Beefs Rock Capital,” The Sporting News, May 27, 1967:18.

Heryford, Merle. “New Resident: Cox Relief Gun,” Dallas Morning News, October 17, 1971: B4.

Whittlesey, Merrell. “Casey at the Bat? A Sad Sight; But He’s A-OK on the Mound,” The Sporting News, February 14, 1970: 36.

Baseball-Reference.com.

Cox’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum library.

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff, eds., Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, 2007),

Author interview with Casey Cox, November 1, 2015.

Notes

1 William Gildea, “This Year Cox Has Batters Buffaloed,” Washington Post, July 9, 1969: C3.

2 Merrell Whittlesey, “French’s Double Emulates Hondo Homers: Cox Joins Catcher in Star Role,” Washington Evening Star, July 8, 1969: 33.

3 Merrell Whittlesey, “Impossible Dream: Ted’s Nats Boast a Carload of ’69 Pluses,” The Sporting News, October 4, 1969: 13.

4 Merrell Whittlesey, “Ted Finally ‘Convinced’ Writers Nats Were for Real,” The Sporting News, October 18, 1969: 27.

5 Bob Addie, “Cocky Young Casey Eyes Nat Relief Job,” The Sporting News, April 9, 1966: 20.

6 “Burlington Stops Rocky Mount on Four Hits: Casey Cox Suffers Heart Breaking Loss,” Rocky Mount (North Carolina) Telegram, June 18, 1962: 2B.

7 Greensboro (North Carolina) Daily News, June 25, 1962: 11.

8 Bob Addie, “Rookie Joseph Casey Cox, 24, Near Life Goal, Exudes Confidence,” Washington Post, March 3, 1966: F1.

9 Author Interview with Casey Cox. All otherwise unattributed quotations come from this interview.

10 Addie, “Cocky Young Casey.”

11 Bob Addie, “Cox Earns Trip North with Nats,” Washington Post, March 30, 1966: C2.

12 Bob Addie, “Cox Provides Some Relief for Nats’ Pitchers, Fans,” Washington Post, April 17, 1966: C4.

13 Merrell Whittlesey, “Cox Convinces Three Doubters,” Washington Evening Star, July 25, 1971: C-3.

14 The Sporting News, December 3, 1966: 59.

15 Ibid.

16 Merrell Whittlesey, “Cox’ Temper a Big Problem in Latin League,” The Sporting News, June 28, 1969: 16.

17 George Minot Jr., “Casey Cox, Nen Signed by Senators,” Washington Post, January 26, 1967: F1.

18 The Sporting News, March 11, 1967: 19.

19 Merrell Whittlesey, “Short Wins Rousing A-OK in Capital Inaugural,” The Sporting News, December 28, 1968: 27.

20 William Gildea, “This Year Cox Has Batters Buffaloed,” Washington Post, July 9,1969: C3

21 George Minot Jr., “Long Relief Effort Gives Cox Victory,” Washington Post, April 27, 1969: 41.

22 The Sporting News, June 21, 1969: 23.

23 Merrell Whittlesey, “Casey Cox Making Capital of Three C’s,” The Sporting News, June 28, 1969: 9.

24 Minot, Washington Post, July 18, 1969: D1.

25 Whittlesey, The Sporting News, March 14, 1970: 20.

26 Merrell Whittlesey, “Nat Rivals Hit Tune Sounds Like a Waltz to Casey,” The Sporting News, May 2, 1970: 19.

27 The Sporting News, July 25, 1970: 30.

28 Merrell Whittlesey, “Cox Perfects His Curve in Winter Ball,” The Sporting News, January 9, 1971: 51.

29 Randy Galloway, “’Old Man’ Cox Leads Ranger Early Birds,” Dallas Morning News, February 18, 1972: B1.

30 Merrell Whittlesey, “Nats’ Cox Relief Whiz, And He Likes the Job,” The Sporting News, August 14, 1971: 15.

31 Merrell Whittlesey, “Cox Adjusts Well to Relief Job,” The Sporting News, August 14, 1971: 20.

Full Name

Joseph Casey Cox

Born

July 3, 1941 at Long Beach, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.