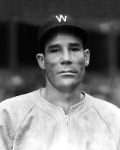

Alex Carrasquel

Alejandro Carrasquel was the first native Venezuelan to play in the major leagues. When the 27-year-old trailblazer joined the Washington Senators in 1939 he was already a seasoned veteran, having pitched for years in countries throughout the Caribbean basin. The Senators that spring were housing an international contingent of players never quite seen before in major league baseball. The camp had three Cuban players and a French Canadian–born pitcher named Joe Krakauskas. Senators owner Clark Griffith partially assessed his team, after a walk around camp, by saying, “The way things are now we sound like a row in the League of Nations.”1

Alejandro Carrasquel was the first native Venezuelan to play in the major leagues. When the 27-year-old trailblazer joined the Washington Senators in 1939 he was already a seasoned veteran, having pitched for years in countries throughout the Caribbean basin. The Senators that spring were housing an international contingent of players never quite seen before in major league baseball. The camp had three Cuban players and a French Canadian–born pitcher named Joe Krakauskas. Senators owner Clark Griffith partially assessed his team, after a walk around camp, by saying, “The way things are now we sound like a row in the League of Nations.”1

Carrasquel had gained the Senators’ notice with his pitching over the previous winter in Cuba, when the right-hander had been named MVP of the Cuban winter league season. Team Cuba’s manager José Rodríguez, former major league player with the New York Giants, alerted Washington to the pitching prospect. The Senators sent scout Joe Cambria to investigate. Cambria, in an often retold account, “trailed him from the Havana park one day and got his name on a Washington contract while they were sitting on a park bench, with an interpreter between.”2

From the mound, Carrasquel showed right off that he was a polished pitcher. He could field his position, hold runners on, and commanded a variety of pitches. Carrasquel easily made the Washington staff. There was an imposed proviso with it, however. The Senators modified Carrasquel’s name to a more fan friendly–sounding “Alex Alexandra.” Alejandro was nicknamed “Patón” [“big-footed”] in Venezuela for his purported size 18 shoes. Former teammate José Zardón said it began one day when Carrasquel accidentally grabbed one of Zardón’s shoes. “Hey, this shoe doesn’t fit. I think it must be yours,” Carrasquel said. “Of course it’s mine,” Zardón replied. “How do you expect my shoe to fit that patón you have?”3

Carrasquel made his first appearance on April 23, 1939, against the New York Yankees at Griffith Stadium. He relieved starter Ken Chase with two outs in the fourth inning and a man on first base. The first three batters he faced were future Hall of Famers Joe DiMaggio, Lou Gehrig, and Bill Dickey. He retired them all, but the Yankees, ahead 6–3 when Carrasquel entered the game, won 7–4.

The Washington Post’s Shirley Povich’s game report contained some colorful but perhaps insensitive language by today’s standards: “Pitching from a big league mound for the first time in his life, Alexandra – who would need only to be climbing over the side of a ship with a cutlass in his teeth to look like one of Lafitte’s fiercest henchmen – gave an amazing exhibition of calm and effectiveness against the Yanks. The Venezuelan, with utter disregard for the reputation of the Yanks, surrendered only one run in the last 5 1/3 innings to the unbridled delight of the 22,000.”4

The game marked the first appearance in the major leagues by a native of Venezuela. Alejandro Eloy Carrasquel was born in Parroquia La Candelaria, a municipality of Caracas, on July 24, 1912. He was the youngest of four children born to Alejo Carrasquero and Emilia María Aparicio, following two brothers and a sister. (Emilia María was not related to the ball-playing Aparicio family eventually rooted in Maracaibo.) A land inheritance left by Carrasquel’s paternal grandmother to Carrasquel’s father forced a generational surname alteration. In court papers, the inheritance was listed bequeathed to Alejo “Carrasquel,” and the spelling error forced Carrasquel’s father to legally change his name in order to accept the holdings.5

Alejandro was signed as an 18-year-old by his country’s Royal Criollos team in 1930 and pitched his first professional game for the club the following spring. Over the next few years, Carrasquel played for several other teams in his homeland, and traveled to pitch in other baseball countries as he gained experience on the mound. Invited by Cuban great Martín Dihigo to join the Cuban winter league in 1938, he made the most of the opportunity, sporting an 11–6 record, with 10 complete games, and caught the eye of the Senators.

In his second major league game, on April 30, Carrasquel picked up his first save. At Yankee Stadium he was called in to relieve in the eighth inning, with two outs and the bases loaded, and Washington clinging to a 3–2 lead. Staying composed, the pitcher coaxed a fly out from Yankees second baseman Joe Gordon, and then retired the side in order in the ninth to preserve the victory.

Three days later, May 3, in another relief role, Carrasquel picked up his first win and the first by a Venezuelan pitcher in the major leagues. The historic victory occurred over the St. Louis Browns at Sportsman’s Park. The Senators rallied from a six-run deficit, scoring seven runs over the final three innings of the game, to pull out an 11–10 road triumph. Hurling scoreless eighth and ninth innings, Carrasquel secured the special win.

The solid relief pitching of the rookie earned him his first big league start on May 14. It came at home against Lefty Grove and the Boston Red Sox. Carrasquel came out on the losing end of a 5–4 score in a strenuous 12-inning battle. Tied at two after nine innings, the Red Sox reached the Washington hurler for three runs in the 12th, and the Nationals’ rally in the bottom of the inning against Grove and two relievers fell one run short. Earlier in the game, Carrasquel recorded the first hit by a Venezuelan player in the major leagues when he singled off Grove. In absorbing his first pitching loss, Carrasquel hung an 0-for-5 on heralded Red Sox rookie left fielder Ted Williams. Incidentally, the Red Sox starting lineup that day had five future Hall of Famers: Grove, Jimmie Foxx, Joe Cronin, Bobby Doerr, and Williams.

Four years later Shirley Povich recalled Carrasquel’s amazing composure as a rookie. “I don’t know where he learned it,” Senators manager Bucky Harris told him back in 1939, “but this big fellow is smoother than any rookie who ever broke in under me.”6 The impressed Harris gave the “big fellow,” who was 6’1” tall — and weighed somewhat more than his listed 182 pounds — three successive starts after the locked-horns effort against Grove. Carrasquel won two of them. All three starts were complete game endeavors.

On May 25, Carrasquel three-hit the Browns, 4–1, at Griffith Stadium. The pitcher gained high praise from Povich with the effort. “Certainly, Alex Alexandra is the most sensational rookie to flash across the big league scene since Bobby Feller appeared in 1936,” wrote the Washington Post’s best-known sportswriter. “That he is no flash in the pan is well established. One only has to look at his past three performances.”7

Not long afterwards, Senators owner Clark Griffith stepped in and ended the name charade. Stripping Carrasquel of his foisted-upon Alexandra alias, Griffin announced to the press that “when a fellow comes that far, I think it’s no more than right that he get all the credit that’s coming to him under his own name.”8

The sole loss in that three-game span for Carrasquel was a 3–1 defeat to the Philadelphia Athletics on May 30. Allowing only four hits and two earned runs, the Caracas-born pitcher supplied his team’s only run with a long ball. At Griffith Stadium, Carrasquel tagged Athletics starter Nels Potter to register the first home run hit by a Venezuelan player in the major leagues. Following the 3–1 loss to the A’s, Carrasquel plodded through several rough outings, winning only once in six more starting appearances.

Carrasquel was honored by a delegation of Venezuelans between games of a doubleheader at Yankee Stadium on the Fourth of July. Dr. Tomás Pacanins, consul general of Venezuela, introduced him and presented several gifts and a diploma from the Venezuelan Baseball Association.9 Alex made a speech – in Spanish – but his part in the occasion has been lost in history because the vast majority of the 61,808 fans had turned out for “Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day,” and Gehrig’s speech and its immortal line, “Today I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of this earth,” overshadowed everything else.

Carrasquel started the second game of the doubleheader, but lasted only three innings, giving up six hits and five earned runs in the Yankees 11–1 victory. His record had been 3–2, with a 2.64 ERA, following the loss to the Athletics on May 30, but his performance declined the rest of the season. He finished with a record of 5–9 and an ERA of 4.69 in 40 games. His 159 1/3 innings pitched, 17 starts, and seven complete games would prove to be career highs, and it was his only losing record in eight major-league seasons.

As a result of his second half decline, Carrasquel needed to prove himself again to the Senators in 1940. His job wasn’t made easier when he reported late to training camp. “Alejandro explained that as steamship service from South America to Cuba is irregular, because of the war, he had to take a boat from his native Venezuela to New York, a longer journey.”10 He made the opening day roster, but faltered in early relief appearances and was optioned to Jersey City of the International League on May 25. He was recalled in the first week of July, and turned things around over the second half of the season. Used exclusively in relief, he pitched only 48 innings in 28 games, and posted an overall 6–2 record, with a 4.88 ERA.

The Washington team Carrasquel reported to in 1941 was distinctively different to the one he had encountered two years earlier. Shirley Povich’s pre-season report had little remaining of the flattery he had once attributed to Carrasquel’s pitching: “The once-populous Latin Legion of the Nats, which for years had set up a babble of Spanish in the Washington camp, has dwindled to one slightly unwanted Venezuelan. . . .The fact that he is still being retained by the Nats is less a tribute to Carrasquel than it is a sad commentary on the state of the Washington pitching.”11

On the year, Carrasquel duplicated his 6–2 record from the prior season and was an overall steady force working primarily out of the Senators’ bullpen. His 3.44 ERA was the best of any of the club’s bullpen specialists, in 96 2/3 innings of work. He started five games late in the season, his first since 1939. By the time August rolled around, his pitching seemed to have warmed the critical Povich. The scribe offered this overview of the previously marginalized pitcher, along with personal snapshots of the man: “Alex Carrasquel, who is the leading percentage pitcher in the American League with six wins and no defeats … he’s Spanish and Indian … in his native Venezuela, he was a mechanic in a Ford factory … he’s the best fielding pitcher on the Washington club, and the best at holding runners close to bases … he dances the rhumba and, in fact, teaches it in his native Caracas . . . he’s continually showing Bucky Harris a new kind of pitch and tosses up more variety of pitching than any man in the league.”12

In 1942, Carrasquel’s fourth year in the league, he had a 7–7 record in 35 appearances. Bucky Harris increased his workload and gave him 15 starts. He finished with a 3.43 ERA in 152 1/3 innings of work. On July 18, the husky pitcher tossed his first major league shutout – the first in the majors by a Venezuelan — blanking the St. Louis Browns 3–0 on five hits and no walks at Griffith Stadium. The pride of Caracas also registered two ten-inning complete game victories during the campaign: a 3–2 win against Detroit at Briggs Stadium on June 21, and a 4–3 home win against Cleveland on September 1.

Owner Clark Griffith hired a new manager for 1943 – Ossie Bluege, a popular 18-year veteran player with the Senators – and Carrasquel had reason to be optimistic about the new season. The persevering right-hander received the following reevaluation from team beat writer Povich in a spring training column:

“With the exception of Dutch Leonard, Alex Carrasquel is now rated the most valuable item on the Nats’ pitching staff. Alex, the Venezuelan, has come a long way with the Nats since that day in 1939 when he checked into the club’s Florida training camp speaking the only three English words he knew, ‘Me peetch gude.’ Carrasquel had a rough time of it in his early years with the Nats. He wasn’t a popular fellow with teammates. The fault was theirs, not his. They resented the presence of the South American. They were fed up, in fact, with all of the Latins the Washington club was importing. The 1000 per cent [sic] Americans on the club viewed the influx as bread being taken from their mouths.

“The Washington players couldn’t pin anything special on Alex. They didn’t like the cut of his clothes, with his fancy padded shoulders, to be sure. But the fact that he looked like a Spaniard and couldn’t speak English was enough. Even the locker room attendants grumbled when Carrasquel and the other Latins sought the routine services in the clubhouse, towels, under socks, perhaps a dry sweatshirt. [The players] didn’t let Carrasquel into their card games, and he was forced into the role of ‘loner,’ even when he was winning five games in a row for the Nats during the 1941 season. Officials of the Washington club stepped in and demanded that Carrasquel get some of the common courtesies.”13

The Senators made a startling improvement under Bluege, finishing in second place with an 84–69 record – 13 ½ games behind the Yankees – compared to seventh place and 62–89 in 1942. The improvement began, as it usually does, with the pitching staff. Carrasquel was one of five hurlers with 11 or more wins. He started 13 games, compiling an 11–7 record, with a 3.68 ERA in 144 1/3 innings pitched. He led the team with 39 appearances, and his 11 wins were a career best. His best performance came early in the year, with a two-hit, 5–0, shutout over the Athletics on April 25.

In 1944, Bluege’s team lost 90 games and dropped all the way down to the cellar of the American League. Carrasquel managed a respectable 8–7 record — though limited to only seven starts – with a 3.43 ERA in 134 innings pitched, and once again led all team hurlers with 43 appearances. His best performance as a starter came on September 10 when he pitched a complete game to defeat the Athletics 8–2, at Griffith Stadium.

Washington was back in a pennant race once again in 1945. At the end of July the Senators were in third place at 45–41, 5 ½ games behind Detroit and only 1 ½ games behind the second-place Yankees. Carrasquel had been used sparingly, pitching only 49 1/3 innings in 20 appearances, and had lost his only start back on May 13. His record stood at 2–3, but he had a fine 2.10 ERA.

However, Carrasquel’s pitching gave Washington a much-needed boost in the final two months of the pennant race. He started six games and relieved in nine others during this stretch. The first four starts were complete-game wins, including two shutouts. He lost to St. Louis 4–3 in a 10-inning complete-game start on September 5, giving up a game-tying homerun to the Browns’ Lou Finney with two outs in the top of the ninth. His final start was a seven-inning no-decision against the White Sox on September 9. Carrasquel finished the season with 7–5 record and a 2.71 ERA in 122 2/3 innings pitched.

Carrasquel was sold to the White Sox on January 2, 1946 for the $7,500 waiver price. Washington scribe Shirley Povich wrote in the January 31 issue of The Sporting News that Senators’ owner Clark Griffith made his decision to cut Carrasquel loose “in a fit of high disgust” after the Venezuelan gave up the two-strike homerun to Finney. According to Povich, “Griffith went to his office and immediately advised [League President] Will Harridge’s office that he was asking waivers on Carrasquel.‘That was the dumbest pitch I ever saw in my 60 years in baseball,’ said Griffith. ‘That Carrasquel wasn’t satisfied to get Finney out. He wanted to strike him out and walk off the field in a blaze of glory, and Finney was laying for it.’ ”14

It is probable that Griffith saw 1945 as his last best chance to win a pennant since all drafted players would be returning from the war in time for the 1946 season, and viewed the Carrasquel-Finney game as one particularly squandered. But it is difficult to see how Griffith could really blame Carrasquel for losing the pennant. The club went 14–8 after the September 5 game, to finish 11/2 games behind Detroit, who were 14–10 over the same span. Actually, the Senators really blew their chances when they lost three of five games to the Tigers in Washington from September 15-18, and followed up by losing three of five games to the Yankees and Athletics to close out the season.

Povich’s January 31 TSN column also carried a paragraph heading reading, “Hit Home Runs, but Pitched ‘Em Too,” reviving an old erroneous claim that Carrasquel gave up too many homeruns. He cited a 1939 game as an example. “Carrasquel hit a home run. It was one of the longest home runs ever hit to the Griffith Stadium left field bleachers. Eventually, he lost the game because a home run was hit against him. ‘That’s the trouble with Alex,’ Bucky Harris [Ossie Bluege’s predecessor as Senators’ manager] moaned, ‘You never know when he’s going to hit a home run or pitch one.’ ”15

In fact, that was Carrasquel’s only homerun in the majors, and he lost the game 3–1 without giving up a homerun. Furthermore, from 1939–45 he gave up 0.43 homeruns per nine innings, compared to the American League average of 0.50.

On January 12, 1946 –less than two weeks after his waiver sale — Alejandro was pitching in Caracas for the Magallanes Navigators. He defeated Cervecería Caracas, 5–2, in the inaugural game of the Venezuelan winter league. Eight days later, Carrasquel and Roy Welmaker of Vargas faced one another in an epic duel, in which both pitchers threw 17 innings before Carrasquel came out on top, 3–2. (Welmaker was a 36-year-old veteran of the Negro Leagues who was 22–12 in 1949 with Cleveland’s Wilkes Barre Class A farm team in his first season in Organized Baseball.)

In mid-February he signed a three-year deal to play in Mexico for Jorge Pasquel’s upstart Mexican League. “Pasquel paid me $3,000 cash [bonus], to sign a three-year contract calling for $10,000 a year,” Carrasquel said, in an interview three years later. “I took it, for in addition to the $33,000 I was to receive in Mexico, I also was free to pitch winter baseball.”16 However, Carrasquel and others who cast their lot with Mexico at that time, were punished with lifetime suspensions by Major League Baseball, and were not permitted to play in Organized Baseball–backed winter leagues.

The league in Mexico had the option of moving a player from team to team for attempted parity purposes, and Carrasquel wound up pitching for several squads over the next three summers. From 1946–48, he pitched for Veracruz, Mexico City, and Monterrey, respectively, with an overall 44–27 record.

While in Mexico, Carrasquel met Eva Guerra of Monterrey. The couple married in January of 1949. It was the third marriage for Carrasquel. He had previously married Caracas native Elvira Estegui. That union produced a son named Jose Alejandro and a daughter christened Rita Emilia. During his time with the Senators, Carrasquel tied the knot with Virginia Catherine Johnson, a native of Takoma Park, Md, shortly after the conclusion of World War II. With Virginia, Carrasquel had two more sons: William Alejandro and Thomas Joseph Blue, the latter preferring to use the surname of his stepfather.

When the “jumpers” ban was lifted in the summer of 1949 by Major League Commissioner Happy Chandler, Carrasquel reported to the Chicago White Sox in early July, but the veteran’s return to the big time was a short one. On August 5, after seeing action in only three games out of the bullpen, Alex was traded to the Detroit Tigers for pitcher Luis Aloma. The next day Detroit optioned the 37-year-old to the Buffalo Bisons of the International League. The move ended his eight-year major league career. The vanguard pitcher compiled a lifetime record of 50–39 with a 3.73 ERA in 861 innings pitched. He appeared in 258 games, recording 30 complete games in 64 starts, along with 16 saves.

With the lifting of his organized baseball suspension, Carrasquel was able to return to the Venezuelan winter league for the 1949–50 season. After pitching two seasons for Cerveceria Caracas, the 40-year-old moundsman rejoined his original club, Magallanes, but pitched very sparingly. In 1953–54, the fading hurler made two appearances with Gavilanes of Venezuela’s Occidental league. These efforts closed out his post–Major League winter pitching career in his homeland. His record of 12–20 in those five years reflected a pitcher past his prime.

Carrasquel bounced around in the minor leagues in the early 1950s and stretched out his pitching tenure until 1956. After his final season with Mexico City in the Class AA Mexican League, Carrasquel returned to the Venezuelan winter league and became a coach with the Caracas Lions. In 1958–59 he was appointed manager of the Pampero Juicers. While guiding the Pampero club to lackluster results during the 1959–60 campaign, he was involved in a serious fight with a team executive. “League officials voted a two-year suspension against Alex Carrasquel who started the season as manager of Pampero,” read the winter league report of the incident. “The ban was imposed because Carrasquel allegedly slugged Eddy Moncada, breaking his jaw in two places, in a dispute which followed Carrasquel’s ouster as pilot.”17 The suspension led to a players’ strike, which caused a shutdown of the entire league. (The vacated season forced Venezuelan officials to send the Occidental league champion as the country’s representative to the Caribbean Series for the first time.)

Carrasquel never managed in the winter league again. However, he had a personal relationship with Rómulo Betancourt, president of Venezuela, and Carrsaquel returned to the diamond in the 1960s when Betancourt asked him to become the manager of the Vigilantes de Tránsito, an amateur league team. He managed the Tránsito club until shortly before his death.

The first Venezuelan major leaguer to win a game, throw a shutout, record a save, hit safely, and stroke a homerun, died from diabetic complications in Caracas in 1969 at the relatively young age of 57. Two years later, the major league trailblazer was inducted into the Venezuelan Sports Hall of Fame.18 In 2003 Alejandro was among a group of 14 – 11 players, one owner, one umpire, and one sportswriter – selected in the inaugural class for the newly-created Venezuelan Baseball Hall of Fame.19

Last revised: August 9, 2021 (zp)

Acknowledgment

Special thanks to Mr. Gil Reyes for providing Venezuelan family data on Carrasquel and his post-winter league life. Additional thanks to Ms. Dana May Blue for furnishing information pertaining to Carrasquel’s U.S. matrimony.

Sources

Books

Figueredo, Jorge S., Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball 1878–1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2003).

Treto Cisneros, Pedro. Enciclopedia del Beisbol Mexicano. 1994 Segunda

Edición Revistas Deportivas, S.A. de C.V. Mexico D.F., 1994.

Newspapers and magazines

Los Angeles Times

The Sporting News

Washington Post

Online sources

1800baseball.com

baseball-reference.com

iconosdevenezuela.com

purapelota.com

museodebeisbol.com.ve

retrosheet.org

Personal Correspondence

Gil Reyes, personal e-mail correspondence with author.

José Zardón, personal interview with author.

Notes

1 “Solons Seek Interpreter,” Los Angeles Times, February 26, 1939, A13.

2 Shirley Povich, “Nats’ Man of Moods Moves to White Sox,” The Sporting News, January 31, 1946, 2.

3 José Zardón, personal interview, March 2011.

4 Shirley Povich, “Champions Get 6 Runs in 4 Innings,” Washington Post, April 24, 1939, 15.

5 Gil Reyes, SABR Luis Castro/Latin American Chapter, personal e-mail correspondence with author, June 17–18, 2014 and June 26–27, 2014.

6 Shirley Povich, “This Morning,” Washington Post, March 12, 1943, 14.

7 Shirley Povich, “This Morning,” Washington Post, June 1, 1939, 18.

8 “American League,” The Sporting News, June 1, 1939, 10.

9 “Alexandra Feted By Countrymen in New York,” Washington Post, July 5, 1939, 16.

10 “Training Camp Notes,” The Sporting News, March 14, 1940, 8.

11 Shirley Povich, “This Morning,” Washington Post, February 23, 1941, S1.

12 Shirley Povich, “This Morning,” Washington Post, August 17, 1941, SP1.

13 Shirley Povich, “This Morning,” Washington Post, March 22, 1943, 14.

14 Shirley Povich, “Nats’ Man of Moods Moves to White Sox,” The Sporting News, January 31, 1946, 2.

15 Ibid.

16 Ray Gillespie, “Carrasquel Threatens Border to Border Jump,” The Sporting News, March 9, 1949, 28.

17 M.J. Gordon, Jr., “King and Tovar Torrid Sockers in Lion Sweep,” The Sporting News, November 25, 1959, 33.

18 http://www.venezuelatuya.com, accessed April 29, 2015.

19 http://www.museodebeisbol.com.ve, accessed April 24, 2015.

Full Name

Alejandro Eloy Carrasquel Aparicio

Born

July 24, 1912 at Caracas, Distrito Federal (Venezuela)

Died

August 19, 1969 at Caracas, Distrito Federal (Venezuela)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.